8. Perceptions of Wiltshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Horse Trail Directions – Westbury to Redhorn Hill

White Horse Trail Route directions (anti-clockwise) split into 10 sections with an alternative for the Cherhill to Alton Barnes section, and including the “short cut” between the Pewsey and Alton Barnes White Horses S1 White Horse Trail directions – Westbury to Redhorn Hill [Amended on 22/5, 26/5 and 27/5/20] Maps: OS Explorer 143, 130, OS Landranger 184, 173 Distance: 13.7 miles (21.9 km) The car park above the Westbury White Horse can be reached either via a street named Newtown in Westbury, which also carries a brown sign pointing the way to Bratton Camp and the White Horse (turn left at the crossroads at the top of the hill), or via Castle Road in Bratton, both off the B3098. Go through the gate by the two information boards, with the car park behind you. Go straight ahead to the top of the escarpment in the area which contains two benches, with the White Horse clearly visible to your right. There are fine views here over the vale below. Go down steps and through the gate to the right and after approx. 10m, before you have reached the White Horse, turn right over a low bank between two tall ramparts. Climb up onto either of them and walk along it, parallel to the car park. This is the Iron Age hill fort of Bratton Camp/Castle. Turn left off it at the end and go over the stile or through the gate to your right, both of which give access to the tarmac road. Turn right onto this. -

White Horse Trail

The White Horse Trail Parish of Broad Town section Condition report Broad Town PC Footpath Working Group Issue 1 December 2018 1 1. Introduction………………………………. Page 2 2. The route through Broad Town………… Page 3 3. Condition Summary……………………... Page 6 4. Route status in detail……………………. Page 7 5. List of tasks required………........……… Page 28 6. Appendix A ………………………………. Page 29 1. Introduction The White Horse Trail is a c90 mile circular way-marked long distance walking trail. It was originally created in 2000 by Wiltshire Ramblers with assistance from Wiltshire Council. The route passes through Pewsey, Marlborough, Broad Town, Cherhill, Devizes, Steeple Ashton and Bratton providing views of eight white horses which are cut into the turf of the chalk hillsides of Wiltshire. The walk runs through some beautiful Wiltshire countryside and also visits fascinating historical sites such as Avebury Stones and Silbury Hill. Other highlights include the Landsdowne Monument near the Cherhill White Horse and there is a long waterside section along the Kennet and Avon Canal through Devizes. The Trail nominally starts at the Westbury White Horse, although the route can be picked up at any point. Guides are available to walk the trail in either a clockwise or anti-clockwise direction. This survey was carried out on the Broad Town section as if walking the route in the clockwise direction. 2 2. The route through Broad Town Travelling the route clockwise, the White Horse Trail enters the parish of Broad Town from Clyffe Pypard. Clyffe Pypard path number CPYP11, joins BTOW8, a bridleway, at grid ref. SU084773. This joins the public road at the top of Thornhill and uses Pye Lane, crosses the B4041 then Chapel Lane turning right at the end of Chapel Lane and continuing up Horns Lane. -

Visit Wiltshire

Great Days Out Wiltshire 2015 visitwiltshire.co.uk Wiltshire: timeless wonders… timeless pleasures… timeless places 2015 promises to be a very special year for Wiltshire Relax with friends and family while sampling traditional as we celebrate 800 years since the signing of Magna Wiltshire specialities at tea shops, pubs and restaurants Carta. Salisbury Cathedral is home to the best around the county. Enjoy a little retail therapy at the preserved original 1215 document, Trowbridge is one designer and factory outlets in Swindon or Wilton, where of the 25 Baron Towns, and exciting events marking this the past meets the present in their historic buildings. Or historic anniversary will take place around the county – browse the many independent retailers to be found in see visitwiltshire.co.uk/magnacarta for details. our charming market towns, uncovering interesting and individual items you won’t find on every high street. Wiltshire is an enchanted place where you feel close to These towns also offer a wide variety of nightlife, with the earth and the ever-changing big skies. Renowned for the city of Salisbury holding Purple Flag status – the its iconic white horses carved into the rolling chalk ‘gold standard’ for a great night out. downs, almost half of our breathtaking landscape falls Wiltshire is a beautiful and diverse county with a within an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and there thriving arts scene covering theatres, cinemas, arts are numerous ways to enjoy this quintessentially English centres and more. Throughout 2015 it will also host a countryside, from walking, cycling and horse-riding to huge range of exciting festivals and events, from music fishing, golf, canal boat trips and more. -

Historic Landscape Character Areas and Their Special Qualities and Features of Significance

Historic Landscape Character Areas and their special qualities and features of significance Volume 1 Third Edition March 2016 Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy Emma Rouse, Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy www.wyvernheritage.co.uk – [email protected] – 01747 870810 March 2016 – Third Edition Summary The North Wessex Downs AONB is one of the most attractive and fascinating landscapes of England and Wales. Its beauty is the result of many centuries of human influence on the countryside and the daily interaction of people with nature. The history of these outstanding landscapes is fundamental to its present‐day appearance and to the importance which society accords it. If these essential qualities are to be retained in the future, as the countryside continues to evolve, it is vital that the heritage of the AONB is understood and valued by those charged with its care and management, and is enjoyed and celebrated by local communities. The North Wessex Downs is an ancient landscape. The archaeology is immensely rich, with many of its monuments ranking among the most impressive in Europe. However, the past is etched in every facet of the landscape – in the fields and woods, tracks and lanes, villages and hamlets – and plays a major part in defining its present‐day character. Despite the importance of individual archaeological and historic sites, the complex story of the North Wessex Downs cannot be fully appreciated without a complementary awareness of the character of the wider historic landscape, its time depth and settlement evolution. This wider character can be broken down into its constituent parts. -

Visit Wiltshire

IT’S TIME FOR WILTSHIRE 2019TRAVEL TRADE GUIDE visitwiltshire.co.uk VISITWILTSHIRE 2019: A great year for group visits to Wiltshire! VisitWiltshire is delighted to including Cholderton, Studley Festivals and events are at the announce the arrival of the Grange and Longleat. Fine heart of the Wiltshire experience. Great West Way, a new 125- examples of our industrial heritage With over 500 fabulous courses mile touring route between can be found at STEAM – Museum to choose from, Marlborough London and Bristol. Offering an of the Great Western Railway College Summer School provides extraordinary variety of English and Wadworth Brewery. While an outstanding programme for all experiences, there’s so much more McArthurGlen Designer Outlet ages. 2019 sees the welcome to it than simply getting from A Swindon offers designer brands at return of the world-renowned to B. The Great West Way is for discounts of up to 60%. Salisbury International the curious. Those who want to Arts Festival, and the 11th explore further and delve deeper. Take time to explore charming Stonehenge Summer Solstice Travellers for whom the journey is market towns such as Corsham and Festival. Wyvern Theatre’s as important as the destination. Bradford on Avon. Stroll through season of music, comedy, Along the Great West Way the the picturesque villages of Lacock drama and more is sure to have timeless rubs shoulders with the and Castle Combe. Or sample something of interest. Looking everyday and, as your visitors Swindon’s entertainment and leisure ahead, Salisbury Cathedral will explore its endless twists and turns, opportunities. Treat yourself in our celebrate a major milestone in they’ll encounter the very essence cafés, pubs and restaurants. -

The Counties

--THE COUNTIES-- AsSOCIATION OF BRITISH COUNTIES NEWSLETTER AUTUMN/WINTER 2009 ) WINCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE GOVERNMENTSTATEMENT 1974: "THE NEW COUNTYBOUNDARIES ARE FOR ADMINISTRATIVE AREAS AND WILL NOT ALTER THE TRADITIONAL BOUNDARIES OF COUNTIES, NOR IS IT INTENDED THAT THE LOYALTIES OR PEOPLE LIVING IN THEM WILL CHANGE." claiming,"Welcome to West Berkshire". Is Berkshire even big enough to have a 'west'?(There The Association of British Counties does seem to be a trend for dividing counties by compass points.) And last year, whilst on my an- President: Michael Bradford nual pilgrimage (holiday) to Scotland I was delighted to see a sign for Naimshire. However, I was Chairman: Peter Boyce slightly bemused to see, on the bisecting road, a sign for administrative' Moray'. You can see what Vice-chairman: Rupert Bames I mean about it being confusing for foreign tourists! Treasurer: Tim Butterworth I'm not really sure when my interest in counties arose but I'm confident I know the 'why'. It stems from my interest in British history and culture and also I suspect, from my keenness for "The Counties" organisation. I'm a collector of postcards (14,000+ atlast count) many of them depicting geo- graphical locations in the British Isles. I organise them properly but that is no easy task. Combin- Editor: Mari Foster ing the internet, maps and Russell Grant's exceptionally useful book, The Real Counties of Brit- Editorial address: 340 Warrington Road, Glazebury, nr Warrington, Lancashire, WA3 5LB ain, I am able to codify my collection successfully. I've even divided my German,Austrian, and email: [email protected] Belgian cards by Hinder or provinces but I find this more straightforward especially with Austria as the 'land' is nearly always printed on the card's reverse. -

Vintage Classics to Launch New Classic Car Tour for 2021 Along the Great West Way on 15Th April 2021 Vintage Classics Will Launc

Vintage Classics to launch new classic car tour for 2021 along the Great West Way On 15th April 2021 Vintage Classics will launch its latest tour for Great West Way visitors. The Wiltshire White Horse Trail starts some 70 miles from London along the Great West Way and takes in a circular route visiting each of the legendary eight White horses carved into the beautiful Wiltshire landscape, many along the The North Wessex Downs and invites exploration of the villages passed through between each – it makes a grand day out for travellers discovering the Great West Way and has some fabulous picnic spots enroute, notably at Cherhill on the A4 near Calne and the historic site of the Westbury White Horse, both affording spectacular views across the county. Vintage Classics will even loan a picnic set or basket and rug free of charge and can recommend picnic providers where clients can pick up a gourmet picnic / afternoon tea enroute. The tour begins in Melksham and heads south to the Westbury White Horse at Bratton Camp (a 2000 year old hill fort), originally carved in 1778 and now the symbol of Wiltshire, it is high on the hillside and as a landmark is visible for miles. It’s a favourite launch pad for colourful hang gliders and from the top you can see across to the Mendips, as well as the White Horses at Alton Barnes and Devizes. Onward to Pewsey, via some incredibly pretty villages that abound across Salisbury Plain, to view their White Horse – a relative newcomer carved in 1937 and then journey to Marlborough College to view their 1804 carving. -

Excursion to Chippenham, Calne, Kellaways, and Corsham

EXCURSION TO CHIPPENHAM, ETC. 339 details of which were kindly given me by Mr. T. Hay Wilson, I should estimate the thickness of the London Clay at High Beach at rather more than 400 ft. Turning eastward from High Beach the party made their way to Loughton Camp. The other pre-historic camp of Epping Forest, known as Ambresbury Banks, has long been known to archseologists, but Lough ton-or, as it is sometimes called, after its discoverer, "Cowper's"·- Camp remained unknown till 1872, when it was accidentally discovered. It is about two miles south-west of Ambresbury Banks. Both camps have been carefully examined by the Essex Field Club, and an account of the exploration of the Loughton Camp may be seen in Trans. Essex Field Club, vol. iii, p. 214 (1884). Its position is one of much greater natural strength than that of Ambresbury Banks, and Mr. W. Cole, who had been a member of the exploration Committee, gave some account of it and of the interesting objects found. Many flint flakes, cores, and one implement were discovered, besides many fragments of rude, hand-made pottery, apparently of pre-Roman date. From the camp, looking south ward, the party enjoyed a fine view over the woodland, and then made their way to Loughton Railway Station. The Director has pleasure in acknowledging the services of Mr. W. Cole and of Mr. T. Hay Wilson' in connection with this Excursion. ~EFERENCES. Geological Survey Map. Sheet I, N.W. 1889. WHITAKER, W.-" Geology of London." j)fem. Ceo!. Survey. BUXTON, E. -

Historic Landscape Character Areas and Their Special Qualities and Features of Significance

Historic Landscape Character Areas and their special qualities and features of significance Volume 1 EXTRACT Third Edition March 2016 Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy Emma Rouse, Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy www.wyvernheritage.co.uk – [email protected] – 01747 870810 March 2016 – Third Edition Summary The North Wessex Downs AONB is one of the most attractive and fascinating landscapes of England and Wales. Its beauty is the result of many centuries of human influence on the countryside and the daily interaction of people with nature. The history of these outstanding landscapes is fundamental to its present‐day appearance and to the importance which society accords it. If these essential qualities are to be retained in the future, as the countryside continues to evolve, it is vital that the heritage of the AONB is understood and valued by those charged with its care and management, and is enjoyed and celebrated by local communities. The North Wessex Downs is an ancient landscape. The archaeology is immensely rich, with many of its monuments ranking among the most impressive in Europe. However, the past is etched in every facet of the landscape – in the fields and woods, tracks and lanes, villages and hamlets – and plays a major part in defining its present‐day character. Despite the importance of individual archaeological and historic sites, the complex story of the North Wessex Downs cannot be fully appreciated without a complementary awareness of the character of the wider historic landscape, its time depth and settlement evolution. This wider character can be broken down into its constituent parts. -

Ali Pretty Podcast Notesv1ap

Ali Pretty Ali Pretty describes herself as the analogue partner in a collaboration that will result in a 100 mile walk that links the 8 white horses on the Wiltshire Downs to take place in August 2013. Working with Richard White, a digital artist, they will create an interactive exhibition including soundscapes, still and video imagery, conversations, and responses to the landscape at the Wiltshire Heritage Museum in Devizes. Ali has an internationally recognised reputation as a painter of large-scale silks, creating carnival costumes and flags for exhibitions and festivals. Through a love of long distance walking she is moving away from the large scale to create a range of silk products inspired by long distance walks. Notes from the podcast interview by Andrew Stuck: Recorded in the garden behind Ali Pretty’s studio offices in East London in June 2013 and published in August 2013 on http:// www.talkingwalking.net Ali Pretty’s website: http://www.aliPretty.co.uk/ Walking Wiltshire’s White Horses – a 100 mile public walk will take place from 22 – 26 August 2013 –find out how you can join in via these websites: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/WalkingWiltshiresWhiteHorses Wiltshire Heritage Museum http://www.wiltshireheritage.org.uk/news/index.php? Action=8&id=161&page=0 Creative Wiltshire: http://www.creativewiltshire.co.uk/walking-wiltshires-white-horses-phase- two.html Salisbury International Arts Festival https://www.salisburyfestival.co.uk/ Festival Director Maria Bota https://www.salisburyfestival.co.uk/the_team.php?t=mariabota Collaborator and Digital Partner Richard White from Creative Wiltshire: http:// www.linkedin.com/pub/richard-white/b/263/22 Devizes Outdoor Celebratory Arts community: http://www.devizescarnival.co.uk/ Ali Pretty’s carnival design company Kinetika: http://www.kinetikaonline.co.uk/ Whittenham Clumps, Oxfordshire http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wittenham_Clumps Walking Wiltshire’s (8) White Horses will be working with primary school children form Devizes and Alton Barnes’ schools. -

2-Year Consolidated Minutes (2018 to December

Minutes of the meeting of Cherhill Parish Council held at Cherhill Village Hall on Tuesday 31 July 2018 at 7.30 pm Present: Martin Purslow - CPC Chairman Paula Purslow - CPC Parish Clerk Anna Shantry – CPC Councillor 18 members of the public David Evans - CPC Councillor David Grafton - CPC Councillor John Cavanagh - CPC Councillor 3460 Apologies Apologies were received from Cllr S Tomlinson and Wiltshire Cllr Alan Hill. 3461 Declaration of Interests There were no declarations of interest. 3462 Public Participation The issue of Redbarn footpath is Minuted under item 3467, although discussed at this time. Mr Chris Caswill expressed his concerns that the post box beside Bell House had been painted black. Cllr J Cavanagh replied that the box had to be painted black because it was no longer operational. Mr Chris Caswill had written to the Parish Council complaining about the slurry smell in Cherhill during the hot spell of weather. Cllr D Grafton replied that strict guidelines on slurry spreading and the exceptionally dry weather had meant that the local farmer was not able to inject the land as it was too hard. Following recent rains the ground had now softened a little and the farmer would now be injecting again, so hopefully the issue would be a one-off incident. 3463 Minutes of meeting held on 5 June 2018 Cllr J Cavanagh approved the Minutes as a correct record, seconded by Cllr D Evans. Cllr M Purslow signed off both sets of Minutes. 3464 Review of Actions Actions were reviewed from the meetings on 5 June 2018. -

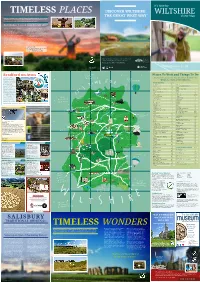

Visitor Map 2021

It’s time for TIMELESS PLACES DISCOVER WILTSHIRE WILTSHIRE ® THE GREAT WEST WAY Visitor Map Wiltshire is rolling green downs, ancient woodlands and bustling market towns. Parish churches, grand historic houses and country inns. Timeless monuments and contemporary luxury. Local ales and picnics in the park. In short, the England you love in one county. “In Wiltshire you can walk through time” > Amesbury > Caen Hill Locks Wiltshire’s charming towns and villages In centuries past, Wiltshire owed its offer numerous ways to connect with the prosperity to railways, canals and the textile past whilst enjoying the present. Stylish industry. As well as the legacy of this rich independent shops and colourful markets. heritage, there are vineyards, breweries and Tempting pubs and restaurants. Fascinating distilleries to visit. Motor and horse racing to history and heritage. Top class entertainment. enjoy. And animal attractions to experience, Wiltshire is particularly renowned for its including the first Safari Park outside of Africa. ancient sites, but later civilisations made their Wiltshire’s museums are great places to mark as well, leaving an exceptional collection unearth the secrets of this journey through of castles, stately homes and manor houses. time. As well as archaeology collections of Set against the drama and majesty of the outstanding national importance, you’ll find Wiltshire landscape their surroundings are exhibits relating to army history, motor equally impressive, from acres of breathtaking vehicles, aviation and more. parkland to intimate formal and informal gardens. Book tickets online You can now book tickets for many places to visit and things to do on our website - just go to: visitwiltshire.co.uk/shop Explore picturesque Pewsey Vale and historic Bradford on Avon along the Great West Way touring route.