Mikhael Subotzky and the Goodman Gallery: Constructions of Cultural Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Afrique Du Sud. Photographie Contemporaine

David Goldblatt, Stalled municipal housing scheme, Kwezidnaledi, Lady Grey, Eastern Cape, 5 August 2006, de la série Intersections Intersected, 2008, archival pigment ink digitally printed on cotton rag paper, 99x127 cm AFRIQUE DU SUD Cours de Nassim Daghighian 2 Quelques photographes et artistes contemporains d'Afrique du Sud (ordre alphabétique) Jordi Bieber ♀ (1966, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) www.jodibieber.com Ilan Godfrey (1980, Johannesburg ; vit à Londres, Grande-Bretagne) www.ilangodfrey.com David Goldblatt (1930, Randfontein, Transvaal, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Kay Hassan (1956, Johannesburg ; vit à Johannesburg) Pieter Hugo (1976, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) www.pieterhugo.com Nomusa Makhubu ♀ (1984, Sebokeng ; vit à Grahamstown) Lebohang Mashiloane (1981, province de l'Etat-Libre) Nandipha Mntambo ♀ (1982, Swaziland ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zwelethu Mthethwa (1960, Durban ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Zanele Muholi ♀ (1972, Umlazi, Durban ; vit à Johannesburg) Riason Naidoo (1970, Chatsworth, Durban ; travaille à la Galerie national d'Afrique du Sud au Cap) Tracey Rose ♀ (1974, Durban, Afrique du Sud ; vit à Johannesburg) Berni Searle ♀ (1964, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit au Cap) Mikhael Subotsky (1981, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Guy Tillim (1962, Johannesburg ; vit au Cap / Cape Town) Nontsikelelo "Lolo" Veleko ♀ (1977, Bodibe, North West Province ; vit à Johannesburg) Alastair Whitton (1969, Glasgow, Ecosse ; vit au Cap) Graeme Williams (1961, Le Cap / Cape Town ; vit à Johannesburg) Références bibliographiques Black, Brown, White. Photography from South Africa, Vienne, Kunsthalle Wien 2006 ENWEZOR, Okwui, Snap Judgments. New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, cat. expo. 10.03.-28.05.06, New York, International Center of Photography / Göttingen, Steidl, 2006 Bamako 2007. -

The Museum of Modern Art Hew York 19

/v THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART No. 110 FOR RELEASE: 11 WEST 53 STREET, NEW YORK 19, N. Y. Wednesday, Oct. k, I96I TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, Oct. 3, I96I 11 a.m. - k p.m. Assemblage, a method initiated by major artists early in this century, which has been Increasingly practiced by young artists here and abroad since World War II, is the flubject of a major exhibition The Art of Assemblage at the Museum of Modern Art from October k through November 12. Two hundred and fifty works by 130 artists were selected for the show by William C. Seitz, Associate Curator, Painting and Sculpture Exhibitions, who has also written the accompanying book.* An "assemblage" (a more inclusive term than the familiar "collage") is a work of art made by fastening together cut or torn pieces of paper, clippings from newspapers, photographs, bits of cloth, fragments of wood, metal or other such materials, shells or 8tones, or even objects such as knives and forks, chairs and tables, parts of dolls and mannequins, and automobile fenders. The symbolic meaning of these objects, not originally intended as art materials, can be as important as their realistic aspects. Seitz writes: When paper is soiled or lacerated, when cloth is worn, stained or torn, when wood is split, weathered or patterned with peeling coats of paint, when metal is bent or rusted, they gain connotations which unmarked materials lack. More specific assocations are denoted when an object can be identified as the sleeve of a shirt, a dinner fork, the leg of a rococo chair, a doll's eye or hand, an automobile bumper or a social security card. -

Liste Des Expostions De La Galerie Stadler.Indd

Expositions de la galerie Rodolphe Stadler 1955 - 1996 1955 1958 Exposition d’ouverture Mark Tobey 7 octobre – 3 novembre 1995 17 janvier – 31 janvier 1958 Carla Accardi, Jacques Delahaye, Gianni Dova, Claire Falkenstein, Ruth Francken, Roger-Edgar Gillet, René Guiette, Philippe Hosiasson, Emil Schumacher – Wilhem Wessel Paul Jenkins, Jeanne Laganne, Iaroslav Serpan, Antoni Tàpies, Mark 11 mars – 10 avril 1958 Tobey Franco Assetto – Franco Garelli René Guiette 15 avril – 8 mai 1958 12 novembre – 2 décembre 1955 Brooks – Carone – Marca-Relli Iaroslav Serpan 13 mai – 31 mai 1958 6 décembre – 30 décembre 1955 Horia Damian 1956 3 juin – 23 juin 1958 Antoni Tàpies Jacques Delahaye 20 janvier – 16 février 1956 24 juin – 13 juillet 1958 Carla Accardi – Jacques Delahaye Jacques Brown 18 février – 8 mars 1956 4 octobre – 28 octobre 1958 Jeanne Laganne Iaroslav Serpan 9 mars – 29 mars 1956 4 novembre – 24 novembre 1958 Expressions et Structures Toshimitsu Imaï 24 avril – 10 mai 1956 25 novembre – 20 décembre 1958 Karel Appel, François Arnal, Jacques Delahaye, René Guiette, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Iaroslav Serpan, Antoni Tàpies 1959 Camille Bryen 16 novembre – 15 décembre 1956 Antonio Saura 17 février – 15 mars 1959 1957 Lucio Fontana – Christo Coetzee Horia Damian 17 mars – 13 avril 1959 15 janvier – 15 février 1957 Antoni Tàpies Toshimitsu Imaï 14 avril – 11 mai 1959 23 février – 16 mars 1957 Sofu Teshigahara Paul Jenkins 14 mai – 11 juin 1959 19 mars – 14 avril 1957 Paul Jenkins Karel Appel 12 juin – 11 juillet 1959 16 avril – 16 mai 1957 Hisao Domoto -

Session 7 April 2021.Indd

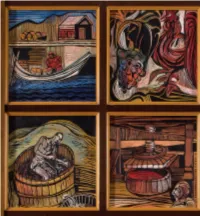

Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Session 7 at 7pm 19th Century, Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art including The KWV Collection, The Metropolitan Life Collection, Property of a Gentleman and Property of a Collector Evening Sale Lots 541–627 Lot 558 Cecil Skotnes, The Origin of Wine/The Epic of Gilgamesh (detail) 133 THE KWV COLLECTION LOTS 541–558 Established in 1918 as a co-operative (Ko-operatiewe Wijnbouwers Vereniging van Zuid-Afrika) by a group of farmers and producers looking to stablise the nascent wine industry, KWV has since become a household name, representing some of South Africa’s, fi nest wines and spirits. The history of the KWV art collection refl ects the origins of the brand with the theme of the Cape winelands recurring throughout. As a corporate collection assembled over the course of some 50 years, the motivation was to purchase established names as well as support local emerging artists who had a relationship with the extended Boland winelands. The result is a fascinating slice through South African art history in which the landscapes refl ect where the fruit of the vine was grown and the interiors suggest where it was consumed and enjoyed. A further 32 lots from The KWV Collection to be sold on the Strauss Online auction, Monday 31 May to 7 June 2021. 541 Cecil Skotnes SOUTH AFRICAN 1926-2009 Wyn wat die Mense-hart © The Estate of Cecil Skotnes | DALRO Verheug (Stillewe) signed oil on board 50 by 50cm R - PROVENANCE In 1977 the Cape Wine Growers In 1979, the same year Skotnes moved earthy tones reminiscent of Cézanne, an The KWV Collection. -

2017 07 31 Leslie Wilson Dissertation Past Black And

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PAST BLACK AND WHITE: THE COLOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-2004 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY BY LESLIE MEREDITH WILSON CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 PAST BLACK AND WHITE: THE COLOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1994-2004 * * * LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xv ABSTRACT xx PREFACE “Colour Photography” 1 INTRODUCTION Fixing the Rainbow: 8 The Development of Color Photography in South Africa CHAPTER 1 Seeking Spirits in Low Light: 40 Santu Mofokeng’s Chasing Shadows CHAPTER 2 Dignity in Crisis: 62 Gideon Mendel’s A Broken Landscape CHAPTER 3 In the Time of Color: 100 David Goldblatt’s Intersections CHAPTER 4 A Waking City: 140 Guy Tillim’s Jo’burg CONCLUSION Beyond the Pale 182 BIBLIOGRAPHY 189 ii LIST OF FIGURES All figures have been removed for copyright reasons. Preface i. Cover of The Reflex, November 1935 ii. E. K. Jones, Die Voorloper, 1939 iii. E. B. King, The Reaper, c. 1935 iv. Will Till, Outa, 1946 v. Broomberg and Chanarin, Kodak Ektachrome 34 1978 frame 4, 2012 vi. Broomberg and Chanarin, Shirley 2, 2012 vii. Broomberg and Chanarin, Ceramic Polaroid Sculpture, 2012. viii. Installation view of Broomberg and Chanarin, The Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement at Goodman Gallery, 2013. ix. “Focusing on Black South Africa: Returning After 8 Years, Kodak Runs into White Anger” illustration, by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., The New York Times x. Gisèle Wulfsohn, Domestic worker, Ilovo, Johannesburg, 1986. Introduction 0.1 South African Airways Advertisement, 1973. -

Complete Catalogue 3

Fine Art Auctioneers Consultants CATALOGUE 3 2 PUBLIC AUCTION BY Fine Art Auctioneers Consultants NORTH/SOUTH Sunday 8 November 2020 Live Virtual Auction Session 1: 11.00am between the Johannesburg and A Private Single-owner Collection of Fine Wines from Cape Town offices of Strauss & Co Renowned Burgundy and Rhône Valley Domaines Modern, Post-War Monday 9 November 2020 and Contemporary Session 2: 10.00am Art, Decorative Arts, Jewellery and Oriental Works of Art Jewellery and Session 3: 2.00pm Fine Wine Interiors: Art, Furniture and Decorative Arts Including A Private Single-owner Session 4: 7.00pm The Tasso Foundation Collection of Important South African Art Collection of Fine Wines from assembled by the Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster Renowned Burgundy and Rhône Valley Domaines; The Tasso Tuesday 10 November 2020 Foundation Collection of Important South African Art assembled by the Session 5: 2.00pm Late Giulio Bertrand of Morgenster; New Collector: South African Ceramics, Selected Prints and Multiples A Focus on South African Ceramics; Session 6: 7.00pm and works from the Late Desmond Contemporary Art Fisher Collection and the Küpper Family Collection. Wednesday 11 November 2020 8–11 November 2020 Session 7: 2.00pm Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art Part I Session 8: 7.00pm Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art Part II Including works from the Late Desmond Fisher Collection and the Küpper Family Collection 3 4 NORTH/SOUTH Live Virtual Auction between the Johannesburg and Cape Town offices of Strauss & Co Modern, Post-War and -

Robert Motherwell

ROBERT MOTHERWELL Born 1915 Aberdeen, WA, United States Died 1991 Provincetown, MA, United States Education 1926 Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles 1932 California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco 1937 Stanford University, Stanford 1938 Harvard University, Cambridge 1940 Columbia University, New York Selected Awards and Honors 1926 Scholarship to the Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles 1964 Guggenheim International Award of Merit, New York 1970 Inducted, National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York Spirit of Achievement Award, Yeshiva University, New York 1973 Honorary Doctorate, Bard College, Annandale-on-the-Hudson 1977 Artist of the Year, State of Connecticut, Hartford 1978 Grande Médaille de Vermeil de la Ville de Paris, Paris 1980 Gold Medal of Merit, University of Salamanca, Salamanca 1981 Mayor’s Award of Honor for Arts and Culture, New York Skowhegan Award for Printmaking, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1983 Gold Medal of Honor, The National Arts Club, New York Gold Medal of Honor, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia 1985 Edward MacDowell Colony Medal, Peterborough Honorary Doctorate, Brown University, Providence Honorary Doctorate, Hunter College, New York Honorary Degree, The New School, New York Inducted, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, New York 1986 La Medalla de Oro de Bellas Artes, Madrid 1987 Wallace Award, American Scottish Foundation, New York Inducted, American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York 1989 National Medal of Arts, Washington, D.C. Centennial Medal of Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge Great Artist Series Award, New York University, New York Selected Solo Exhibitions Please see www.dedalusfoundation.org for a complete exhibition history. -

Abstraction: South African Art from the 50S to the 70S

WWelgemeendelgemeend AAugustugust AArtrt MMonthonth 22017017 AAbstraction:bstraction: SSouthouth AAfricanfrican AArtrt ffromrom tthehe 550s0s ttoo tthehe 770s0s EExhibitionxhibition CatalogueCatalogue Abstraction: South African Art from the 50s to the 70s from the Frank and Lizelle Kilbourn Collection and the Pieter G. Colyn Collection Welgemeend, August 2017 Welgemeend, cnr Welgemeend and Lingen Street, Gardens, Cape Town Introduction 2017 marks the fourth instalment of the annual Graff Estate, Hoërskool Jan van Riebeeck and besondere werke van daardie tydvak, in al hul August Art Month at Welgemeend, a month-long Strauss & Co. kleur- en vindingryke verskeidenheid, te waardeer exhibition of South African art at one of Cape en te geniet! Town’s most renowned manor homes. Bina Genovese, Joint Managing Director, Strauss & Co Dit bly ’n voorreg om die uitstalling jaarliks te kan The theme for this year’s exhibition is “Abstraction aanbied en fondse in te samel met die wonderlike - South African art from the 50’s to the 70’s” and The annual Welgemeend art month has become ondersteuning van die Vriende van Welgemeend, will showcase work from two important private a highlight on the Kilbourn family’s calendar. Helena en haar span, die Kilbourn familie kantoor, collections, the Frank and Lizelle Kilbourn It presents an opportunity for us to combine our Strauss & Co, Delaire Graff Landgoed, Caro Wiese Collection and Pieter G. Colyn Collection. passion for art, conservation and education. en die kunsliefhebbers van Kaapstad en omstreke. August Art Month is the brainchild of collector Lizelle and I enjoy sharing our art collection with Dankie daarvoor! Frank Kilbourn and Stephan Welz, the former our friends, fellow collectors and other art lovers. -

1 7 June 2 0

H E R M A N U S 8-17 JUNE 2018 There it is - Strijdom van der Merwe, mild steel. 3.5m X150mm X 1.2 m - Sculpture on the Cliffs 2018 Contents & General Information CONTENTS & GENERAL INFORMATION FINDING YOUR WAY AROUND THE BOOKLET Welcome 2 • Each of the series of events making up the 2018 programme is Growing with FynArts 4 colour-coded in the side margins. Performances 5 • The colour band at the top of the first page of each section Walkabouts and Tours 14 includes general information about that series. Exhibitions - Festival Artist 15 Exhibitions - Sculpture on the Cliffs 16 • A colour-coded summary of the daily events programme appears on pages 48 and 49, in the middle of the booklet. Map - Art and Wine Route 20 Exhibitions - Tollman Bouchard Finlayson Art Award 21 • A map of FynArts venues appears as a fold-out page attached Exhibitions - Art on the Wine Route 22 to the back cover. The Hermanus Art and Wine Route is on page 20. Art in the Auditorium - Group Sculpture Exhibition 25 Exhibitions - Ceramics 28 Exhibitions - Collaborative Relationships 34 Exhibitions - Galleries 39 TICKET SALES Exhibitions - Jewellery 45 Tickets may be purchased on-line at Exhibitions - Diverse 46 webtickets.co.za Programme Summary - 8 - 12 June 48 Programme Summary - 13 - 17 June 49 or via the Hermanus FynArts website at hermanusfynarts.co.za Strauss & Co - Lecture Series 51 Readings - Books and Poetry 59 Tickets are also for sale at Workshops 60 Demonstrations - Chefs 71 • the Tourism Office, Station Building, Mitchell Street • by telephone on 060 957 5371 / 028 312 2629 Wine Plus - Tutored Tastings 74 Blending and Tasting 76 Opening hours: Pairings - Lunch - Supper 78 Films 80 Monday - Friday 9:00 - 17:00 Saturday 9:00 - 15:00 Reaching Out 83 For Children 86 Extended hours will apply during the ten days of the festival. -

Gutai À Paris Dans Les Années 1960 : Michel Tapié, La Galerie Stadler Et L'histoire D'une Rencontre Manquée

https://lib.uliege.be https://matheo.uliege.be Gutai à Paris dans les années 1960 : Michel Tapié, la galerie Stadler et l'histoire d'une rencontre manquée Auteur : Piron, Lucie Promoteur(s) : Bawin, Julie Faculté : Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres Diplôme : Master en histoire de l'art et archéologie, orientation générale, à finalité approfondie Année académique : 2019-2020 URI/URL : http://hdl.handle.net/2268.2/9471 Avertissement à l'attention des usagers : Tous les documents placés en accès ouvert sur le site le site MatheO sont protégés par le droit d'auteur. Conformément aux principes énoncés par la "Budapest Open Access Initiative"(BOAI, 2002), l'utilisateur du site peut lire, télécharger, copier, transmettre, imprimer, chercher ou faire un lien vers le texte intégral de ces documents, les disséquer pour les indexer, s'en servir de données pour un logiciel, ou s'en servir à toute autre fin légale (ou prévue par la réglementation relative au droit d'auteur). Toute utilisation du document à des fins commerciales est strictement interdite. Par ailleurs, l'utilisateur s'engage à respecter les droits moraux de l'auteur, principalement le droit à l'intégrité de l'oeuvre et le droit de paternité et ce dans toute utilisation que l'utilisateur entreprend. Ainsi, à titre d'exemple, lorsqu'il reproduira un document par extrait ou dans son intégralité, l'utilisateur citera de manière complète les sources telles que mentionnées ci-dessus. Toute utilisation non explicitement autorisée ci-avant (telle que par exemple, la modification du document ou son résumé) nécessite l'autorisation préalable et expresse des auteurs ou de leurs ayants droit. -

Regional Assessment on Ecosystem-Based Disaster Risk Reduction and Biodiversity in Eastern and Southern Africa About IUCN

Regional Assessment on Ecosystem-based Disaster Risk Reduction and Biodiversity in Eastern and Southern Africa About IUCN IUCN is a membership Union uniquely composed of both government and civil society organisations. It provides public, private and non-governmental organisations with the knowledge and tools that enable human progress, economic development and nature conservation to take place together. Created in 1948, IUCN is now the world’s largest and most diverse environmental network, harnessing the knowledge, resources and reach of 1,300 Member organisations and some 15,000 experts. It is a leading provider of conservation data, assessments and analysis. Its broad membership enables IUCN to fill the role of incubator and trusted repository of best practices, tools and international standards. IUCN provides a neutral space in which diverse stakeholders including governments, NGOs, scientists, businesses, local communities, indigenous peoples organisations and others can work together to forge and implement solutions to environmental challenges and achieve sustainable development. Working with many partners and supporters, IUCN implements a large and diverse portfolio of conservation projects worldwide. Combining the latest science with the traditional knowledge of local communities, these projects work to reverse habitat loss, restore ecosystems and improve people’s well-being. www.iucn.org https://twitter.com/IUCN/ Acknowledgements This Regional Assessment was carried out through the project, “Resilience through Investing in Ecosystems - knowledge, innovation and transformation of risk management (RELIEF-Kit)” led by the IUCN Global Ecosystem Management Programme and implemented by IUCN ESARO in eastern and southern Africa, with financial support from the Japan Biodiversity Fund (JBF) under the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity.