Improving the Cambodian Palm Sugar Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Sap Sources, Characteristics, and Utilization in Indonesia

Journal of Food and Nutrition Research, 2018, Vol. 6, No. 9, 590-596 Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/jfnr/6/9/8 © Science and Education Publishing DOI:10.12691/jfnr-6-9-8 Palm Sap Sources, Characteristics, and Utilization in Indonesia Teguh Kurniawan1,*, Jayanudin1,*, Indar Kustiningsih1, Mochamad Adha Firdaus2 1Chemical Engineering Department, Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa, Cilegon, Indonesia 2Chemical Engineering Department, King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding author: [email protected]; [email protected] Received August 15, 2018; Revised September 19, 2018; Accepted September 28, 2018 Abstract Sap from various species palm trees in which known as neera generally produced by traditional technology in Indonesia. There are 5 well known palm species that produce Neera in Indonesia such as arenga palm, coconut tree, doub palm, nipa palm and palm oil. Neera can be utilized as raw material for various derivatives such as palm sugar, sweet palm toddy, and alcoholic toddy. Tapping of neera is a crucial step because neera prone to immediately degrade and causing poor quality of palm sugar. Traditional sugar processing has some drawbacks for example: low energy efficiency processing and off-specification products. On the other side, sugar palm neera has important antioxidant component which benefits for human that unavailable in normal white sugar from sugarcane. In this current review, characterization of neera from various palms in Indonesia and available technology on sugar palm processing such as spray dryer and membrane ultrafiltration will be discussed. Keywords: neera, palm sugar, antioxidant, spray dryer, membrane Cite This Article: Teguh Kurniawan, Jayanudin, Indar Kustiningsih, and Mochamad Adha Firdaus, ―Palm Sap Sources, Characteristics, and Utilization in Indonesia.‖ Journal of Food and Nutrition Research, vol. -

Organic Palm Sugar Crystal

KSU JATIROGO Organic Palm Sugar Crystal Purwokerto, Desember 17 2015 Who is KSU Jatirogo?? • KSU Jatirogo is a producer cooperative of organic gardening/ platation product is built on Nov 26, 2008 by meaning to sertificating organic garden and oproduct, especially organic brown-sugarto increase the presperity of brown coconut sugar farmer in KulonProgo area. KSU Jatirogo get Legalization No 24/BH from Regent of KulonProgo on December 2008 • Opertional KSU Jatirogo includes 26 hamlets 5 villages in 2 districts :Kokap, Samigaluh and Girimulyo. In those areas 1731 of farmers who have cultivated land to with width 792,52 Ha which have ceriticated organic by 3 International organic standart, certification by Control Union Certification (CUC) Where there is KSU Jatirogo? KSU Jatirogo is exist to increase bargain positian of brown coconut sugar farmer in quality, type and price product. So except from the activity which is done by KSU Jatirego and its member is able to make economic changeof society especially for brown coconut sugar farmer and in general and all members of KSU Jatirogo. ORGANIZATION of STRUCTURE RUA (Publicmeeting Of Member) ORGANIZER ADVISOR MANAGER QUARANTEEING PRODUCTION & MEMBERSHI AND ADM &FINANANCE OF QUALITY LOGISTIC ENERGY SECTION OF SECTION SECTIOIN SECTON FORMATION of ORGANIZER • Leader : Ngatijo • Secretari : Albani • Freasure : Susanto • In doing the activites KSU jatirogoorganizer,have responsibility to orrange long and short term programe. • The organizers get compensation from their apligation. FORMATION of CENTIOLER -

The Toxic Impact of Honey Adulteration: a Review

foods Review The Toxic Impact of Honey Adulteration: A Review Rafieh Fakhlaei 1, Jinap Selamat 1,2,*, Alfi Khatib 3,4, Ahmad Faizal Abdull Razis 2,5 , Rashidah Sukor 2 , Syahida Ahmad 6 and Arman Amani Babadi 7 1 Food Safety and Food Integrity (FOSFI), Institute of Tropical Agriculture and Food Security, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; rafi[email protected] 2 Department of Food Science, Faculty of Food Science and Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.F.A.R.); [email protected] (R.S.) 3 Pharmacognosy Research Group, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuantan 25200, Pahang Darul Makmur, Malaysia; alfi[email protected] 4 Faculty of Pharmacy, Airlangga University, Surabaya 60155, Indonesia 5 Natural Medicines and Products Research Laboratory, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia 6 Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biotechnology & Biomolecular Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] 7 School of Energy and Power Engineering, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang 212013, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +6-038-9769-1099 Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 11 September 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: Honey is characterized as a natural and raw foodstuff that can be consumed not only as a sweetener but also as medicine due to its therapeutic impact on human health. It is prone to adulterants caused by humans that manipulate the quality of honey. Although honey consumption has remarkably increased in the last few years all around the world, the safety of honey is not assessed and monitored regularly. -

The Sugar Palm Tree As the Basis of Integrated Farming Systems in Cambodia

Livestock Feed Resources within Integrated Farming Systems 83 The Sugar Palm Tree As the Basis of Integrated Farming Systems in Cambodia Khieu Borin Department of Animal Health and Production, Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries, Cambodia Abstract The sugar palm tree (Borassus flabellifer) plays an important role in the small integrated farming systems in Cambodia. The sugar palm is considered to be a multi-purpose tree and provides different products such as juice, sugar, leaves, timber, fruits, underground seedlings and roots. The juice from the sugar palm is rich in highly digestible carbohydrate (sugars) which is an alternative energy source for animal feeding in the rural areas. The impact of the sugar palm on the farming system is increased when the excreta from the animals is recycled through biodigesters to provide gas for household cooking and effluent to fertilize the pond which can produce fish or water plants, the former for the household and the latter for the livestock. When sugar palm juice is used for pig feeding, rather than the making of sugar, it is better from both the economic and environmental points of view, because sugar production requires large amounts of firewood that makes the cost of production very high. It is even less profitable and extremely harmful to the environment when palm trees are used as fuel in order to produce the sugar. KEY WORDS: Borassus flabellifer, palm juice, palm sugar, fuel, environment, biodigester, sustainable production 84 The Sugar Palm Tree as the Basis of Integrated Farming in Cambodia Introduction In Cambodia, 85 per cent of the total population is dependent on agricultural activities. -

Advanced Palmyra Sugar Processing in India

About Green Agro Exim:- Green Agro Exim Private Limited Company is located in South India. We specialize in sourcing, processing and supplying good quality Palmyra products. It is an ISO22000 – 2005 certified company. We mainly deal with Palm Sugar, Palm Jaggery. Our product is proved to be Traditional Product. Our core concept is "Product Quality is the base of an enterprise's existence; Sincere Customer service is our root; Exceptional Quality, Practicality, Customer Satisfaction." We hope to establish reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationships with customers both at home and abroad. We sincerely welcome clients to cooperate with us based on mutual benefit to create a bright future with you. Why you have to buy Natural Palmyra Sugar from us :- Advanced Palmyra sugar processing in India:- We procure Palm sugar, Palm Jaggery directly from selective farmers in South Tamil Nadu sea sourer areas. The farmers are adopting GMP in their production as per our quality team advices. In our unit it is sieved, pre cleaning and packed by HACCP process flow CCP’s quality management aspect. In India we are the first person having ISO 22000-2005 certificate in Palm sugar processing. Our ability to supply the bulk orders of our customers within a short time span. Profile: - The person born at southern part of India in a small village with middle class Agricultural Family played in and around of Coconut and Palmyra trees holding diploma in Agricultural and Master of Business and administration. Having 25 years of Experience in Agricultural products marketing in domestic market, 18 years’ experience in Palm sugar. -

(Arenga Pinnata) Potential of Sugar Palm for Bio-Ethanol Production

Sugar palm (Arenga pinnata) Potential of sugar palm for bio-ethanol production Prepared by FACT Foundation Sugar palm harvesting ( foto: Maut Star Bussman) FACT Project no: 146/WW/001 Authors: Wolter Elberson (WUR- AFSG), Leo Oyen (WUR-PROTA) Translation and editing: Ywe Jan Franken (FACT Foundation) Date: 15-3-2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE 1 1.1 FOREWORD 1 1.2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 1.3 ORIGINAL PUBLICATION DATA 1 2 SUMMARY 2 3 BIO-ENERGY POTENTIAL OF SUGAR PALM 3 3.1 CENTER OF ORIGIN AND CLIMATE AND SOIL REQUIREMENTS 3 3.2 CURRENT DISTRIBUTION AND STATUS AS AN ENERGY CROP 3 3.3 DESCRIPTION OF THE CROP 3 3.4 GROWTH PROPAGATION AND PLANTING 4 3.5 PLANTATION MANAGEMENT 5 3.6 PESTS AND DISEASES 5 3.7 HARVESTING 5 3.8 YIELDS AND CONVERSION INTO BIOFUEL 5 3.9 TRADITIONAL USES 7 3.9.1 Sugars 7 3.9.2 Fibers 7 3.9.3 Other uses 8 3.10 ECONOMY 8 3.11 SUSTAINABILITY 8 i 1 PREFACE 1.1 Foreword This FACT sheet is based on a Dutch report on biofuels, prepared by Wageningen University in the Netherlands. FACT has translated the document from Dutch into English with the intention of making it available to largest possible audience. The main target groups of this document are parties involved in the development of sustainable biofuels in developing countries (NGO’s, small and medium Sized Enterprises, local entrepreneurs, local governments, local farmers and farmers groups). We hope the document helps in making well balanced decisions in new research and projects involving sugar palm. -

Processing of Arenga Pinnata (Palm) Sugar

PROCESSING OF ARENGA PINNATA (PALM) SUGAR Inneke Roos Mary Victor Department of Bioresource Engineering Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Macdonald Campus of McGill University Sainte-Anne-De-Bellevue, Québec, Canada January 2015 A Thesis Submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Inneke Roos Mary Victor 2015 1 ABSTRACT Arenga pinnata sugar has been consumed by the local people of Indonesia for decades. In Tomohon, Indonesia, the sugar has been processed following the indigenous knowledge which consists of minimal process parameters. The sugar is considered to be potentially better for your health for which sufficient information is not yet available. This study has focused on developing knowledge on the process parameters involved in producing Arenga pinnata sugar from the sap, which is needed to improve existing process techniques to enhance the quality of produced sugar, and on the characterization of the sugar which will help the farmers to gain a better market positioning for their sugar. The first study investigated the changes in Arenga pinnata sap, as a raw material, following the harvesting identified by pH, invert sugar and colour changes. As the time increased, the pH of the sap decreased and the invert sugar increased. Colour measurements following CIELAB (L*a*b* colour space) indicated that the change in pH of the sap is more associated with L* and b* values. The results confirmed the hypothesis that these parameters can be used as indicators of deterioration of the sap. Processing the sap into sugar, by the removal of water through boiling, was carried out in the second study. -

Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food: Draft Guidance for Industry1

Contains Non-binding Recommendations Draft-Not for Implementation Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food: Draft 1 Guidance for Industry This draft guidance, when finalized, will represent the current thinking of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or we) on this topic. It does not establish any rights for any person and is not binding on FDA or the public. You can use an alternative approach if it satisfies the requirements of the applicable statutes and regulations. To discuss an alternative approach, contact FDA’s Technical Assistance Network by submitting your question at https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/FSMA/ucm459719.htm. Appendix 1: Potential Hazards for Foods and Processes Appendix Organization This appendix contains information on the potential biological, chemical, and physical hazards that are food- related and process related. The potential hazard information presented covers the following 17 food (including ingredients and raw materials) categories: • Bakery • Beverage • Chocolate and Candy • Dairy • Dressings and Condiments • Egg • Food Additives • Fruits and Vegetables • Game Meat • Grains • Multi-Component Foods (such as a refrigerated entrée or a sandwich) • Nuts • Oil 1 This guidance has been prepared by the Office of Food Safety in the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Underlined text in yellow highlights represents a correction from the draft Appendix 1 that we issued for public comment in August 2016. Appendix 1 (Tables of Potential Hazards) - Page 1 Contains Non-binding Recommendations Draft-Not for Implementation • Snack Foods • Soups • Spice • Sweeteners To help you to identify food-related and process-related hazards for the food categories listed above, this appendix contains three series of tables: • Tables 1A through 1Q contain information that you should consider for potential food-related biological hazards. -

Study on the Processing of Quality Improvement of Myanmar Palm Sugar

Title Study on the Processing of Quality Improvement of Myanmar Palm Sugar Author Khin Si Win Issue Date 1 Study on the Processing of Quality Improvement of Myanmar Palm Sugar Khin Si Win* [email protected] Abstract Toddy palm jaggery (Myanmar name: Htan-Nyet) is a very important sweet foodstuff in Myanmar. In this study, the characteristics of toddy fresh saps were determined by Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) method. The effects of storage time on pH of toddy fresh saps (without and with liming) from Thanlyin Township, Yangon Region (TLT) and Pyinmana Township, Mandalay Region (PMT) were investigated. The pH adjustment of toddy fresh sap was carried out by using 10 ml of 5° Be′ milk of lime. An effective production technique was employed to obtain both high quality palm jaggery and palm sugar from toddy fresh sap and processed jaggery. The most suitable conditions for jaggery production were found to be 70 °C and pH 7.5. High quality palm jaggery (an average yield of 14 -18 % based on the palm sap weight) was produced by using a vacuum evaporator. The quality of processed palm jaggeries was determined by AOAC method and compared with those of palm jaggeries from local market. Palm sugar was produced from toddy fresh sap and processed jaggeries at the most suitable temperature of 60o C and pH of 5.5 in a vacuum evaporator to substitute cane sugar in confectioneries. The characteristics of processed palm sugar was also determined by AOAC method and compared with those of commercial palm sugar from local market. -

Exporting Honey and Sweeteners to Europe

Exporting Honey and Sweeteners to Europe Exporting Honey and Sweeteners to Europe Contents: Sector information What competition do you face? Which trends offer opportunities? Through what channels can you get honey onto the European market? What requirements should your product comply with? What is the demand? Source : CBI, Centre for the Promotion of Imports from Developing Countries, www.cbi.eu Exporting Honey and Sweeteners to Europe Europe offers interesting opportunities for exporters of honey and sweeteners. this information can help you make use of these opportunities. Sector information What competition do you face? Which trends offer opportunities? Through what channels can you get honey onto the European market? What requirements should your product comply with? What is the demand? What competition do you face on the European honey market? Competition in the European honey market is falling both at a product level and at the company level. The increased European demand for honey and the insufficient supplies put exporters from developing countries (DCs) in a very favourable position. Indeed, this is the perfect time to enter the European honey market. Contents of this Trend 1- What are the opportunities and barriers when I try to access the honey market? 2- What are the most popular substitutes for honey in the European market? 3- Who are my rivals when I am exporting honey to the EU market? 4- How much power do I have as a supplier? 1- What are the opportunities and barriers when I try to access the honey market? Low entry barriers Technology and capital needs for the production of honey are relatively low compared to other sectors. -

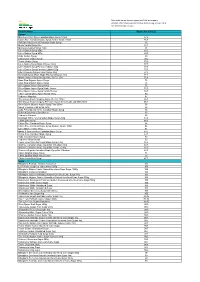

Honey and Syrups Data

Data table sorted highest sugars per 100g by category Product information was collected in store during January 2019 NP; Not Provided on pack Product Name Sugars Per 100 ( g ) Syrups Morrisons 100% Pure Canadian Maple Syrup 189ml 87.6 Clarks Pure Canadian Maple Syrup Amber Grade 180ml 85.7 Aldi Specially Selected Canadian Maple Syrup 85 Monin Vanilla Syrup 25cl 83.7 Morrisons Golden Syrup 750g 81 Lyle's Golden Syrup 454g 80.5 Lyle's Golden Syrup 907g 80.5 Asda Golden Syrup 80 Sainsbury's Golden Syrup 79.9 Tesco Golden Syrup 79.9 Lyles Golden Syrup Maple Flavour 340g 77.5 Lyle's Golden Syrup Pancake Edition 340g 77.5 Lyle's Golden Syrup Pancake Edition 600g 77.5 Lyle's Squeezy Syrup Golden Syrup 325g 77.5 Buckwud Syrup Shack Maple Flavoured Syrup 240g 77.1 Monin Caramel Syrup for Speciality Coffee 25cl 76.4 Aqua Riva Organic Agave Syrup 75 Aqua Riva Organic Agave Syrup 75 Silver Spoon Golden Syrup 680g 75 Silver Spoon Agave Syrup Maple flavour 72.5 Silver Spoon Agave Syrup Vanilla Flavour 72.5 Tate + Lyle Organic Agave Nectar 310g 69 Vedrenne Hazelnut 67 The Groovy Food Company Agave Nectar 250ml 66.1 The Groovy Food Company Premium Agave Nectar Light and Mild 250ml 66.1 Silver Spoon Organic Agave Syrup Plain 250ml 66 Sweet Freedom Fruit Syrup 350g 66 Asda Extra Special 100% Canadian Maple Syrup 65 Beloved Datelicious Date Nectar 65 Vedrenne Caramel 65 Buckwud 100% Pure Canadian Maple Syrup 250g 64.6 Clarks Date Syrup 64.1 Clarks Pure Canadian Maple Syrup 64 Clarks Pure Canadian Maple Syrup Medium Grade 180ml 64 Lyle's Black Treacle 454g -

Fructose Intolerance (Fructose Malabsorption)

Fructose Intolerance (fructose malabsorption) What is Fructose? Fructose is a sugar found in fruit and is a basic component of table sugar called sucrose. If you have fructose intolerance you should avoid foods that contain fructose and sucrose. Sorbitol, a sugar-alcohol, is converted to frutose during digestion, should be avoided as well. It is important to understand that there are two types of fructose intolerance. Hereditary fructose intoler- ance is a rare genetic disorder in which a person does not have the enzyme to break down fructose in the digestive system. This is a more serious disorder and can lead to liver and kidney disease. A second, less serious disorder is fructose malabsorption or dietary fructose intolerance. People with fructose malabsorption have difficulty digesting fructose. This disorder does not cause liver and kidney damage but can result in a variety of symptoms. What are the symptoms of fructose malabsorption? Symptoms very from person to person in severity but in general include bloating, abdominal pain, diar- rhea, headache, weight loss and fatigue. How is fructose malabsorbtion diagnosed? Fructose intolerance is diagnosed with a simple breath test. After some fasting requirements and medi- cation and dietary restrictions the patient is given a substance to drink. Occasionally, patients may be in- tolerant to more than one substance so your doctor may order more that one test. The substance used to test for small bowel bacterial overgrowth is glucose; lactose is used to test for intolerance of milk prod- ucts; and fructose for fructose intolerance. Glucose, lactose and fructose are all sugars and intolerance to any can result in the same type of symptoms.