Mountain Quail Translocations in Eastern Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forests of Eastern Oregon: an Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann

Forests of Eastern Oregon: An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann United States Forest Pacific Northwest General Tecnical Report Department of Service Research Station PNW-GTR-578 Agriculture April 2003 Revised 2004 Joseph area, eastern Oregon. Photo by Tom Iraci Authors Sally Campbell is a biological scientist, Dave Azuma is a research forester, and Dale Weyermann is geographic information system manager, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 620 SW Main, Portland, OR 97205. Cover: Aspen, Umatilla National Forest. Photo by Tom Iraci Forests of Eastern Oregon: An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, OR April 2003 State Forester’s Welcome Dear Reader: The Oregon Department of Forestry and the USDA Forest Service invite you to read this overview of eastern Oregon forests, which provides highlights from recent forest inventories.This publication has been made possible by the USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program, with support from the Oregon Department of Forestry. This report was developed from data gathered by the FIA in eastern Oregon’s forests in 1998 and 1999, and has been supplemented by inventories from Oregon’s national forests between 1993 and 1996.This report and other analyses of FIA inventory data will be extremely useful as we evaluate fire management strategies, opportunities for improving rural economies, and other elements of forest management in eastern Oregon.We greatly appreciate FIA’s willingness to work with the researchers, analysts, policymakers, and the general public to collect, analyze, and distrib- ute information about Oregon’s forests. -

The Harney County Way Collaborative Summit May 2 – 3, 2018 | Lincoln Building Auditorium, Burns, OR

The Harney County Way Collaborative Summit May 2 – 3, 2018 | Lincoln Building Auditorium, Burns, OR The Harney County Way Collaborative Summit 2018 Linking Collaboration Efforts to Build a Best Harney County High Desert Partnership’s Mission Summit Vision The High Desert Partnership exists to cultivate collaboration and We believe this summit will provide a productive time for those support and strengthen diverse partners engaged in solving participating in collaborative work in Harney County to network, complex issues to advance healthy ecosystems, economic well- learn and look for opportunities to work together. Bringing together being and social vitality to ensure a thriving and resilient the collaborative initiatives will create synergy and the story of community. collaboration will reverberate in our community. The outcomes from this summit will lead to more resilient communities. Our Core Values o We believe in our collaborative process to address societal Goals of the Summit issues. o Increase the understanding of collaborative efforts in Harney o We believe in doing things right rather than right now. County. o We believe in recognizing the values of others. o Understand the links where initiatives can work together on o We believe in advocating for the process, not for outcomes. projects or programs. o We believe in taking a holistic approach: social, ecological and o Find the places for sharing resources. economic. o Grow the community's collaborative participation. o We believe that optimism is necessary to successfully address o Provide a venue for those in attendance to gain a better the challenges we face. understanding of the work of High Desert Partnership. -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Historical and Current Forest and Range Landscapes in the Interior

United States Department of Historical and Current Forest Agriculture Forest Service and Range Landscapes in the Pacific Northwest Research Station United States Interior Columbia River Basin Department of the Interior and Portions of the Klamath Bureau of Land Management General Technical and Great Basins Report PNW-GTR-458 September 1999 Part 1: Linking Vegetation Patterns and Landscape Vulnerability to Potential Insect and Pathogen Disturbances Authors PAUL F. HESSBURG is a research plant pathologist and R. BRION SALTER is a GIS analyst, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 1133 N. Western Avenue, Wenatchee, WA 98801; BRADLEY G. SMITH is a quantitative ecologist, Pacific Northwest Region, Deschutes National Forest, 1645 Highway 20 E., Bend, OR 97701; SCOTT D. KREITER is a GIS analyst, Wenatchee, WA; CRAIG A. MILLER is a geographer, Wenatchee, WA; CECILIA H. McNICOLL was a plant ecol- ogist, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, and is currently at Pike and San Isabel National Forests, Leadville Ranger District, Leadville, CO 80461; and WENDEL J. HANN was the regional ecologist, Northern Region, Intermountain Fire Sciences Laboratory, and is currently the National Landscape Ecologist stationed at White River National Forest, Dillon Ranger District, Silverthorne, CO 80498. Historical and Current Forest and Range Landscapes in the Interior Columbia River Basin and Portions of the Klamath and Great Basins Part 1: Linking Vegetation Patterns and Landscape Vulnerability to Potential Insect and Pathogen Disturbances Paul F. Hessburg, Bradley G. Smith, Scott D. Kreiter, Craig A. Miller, R. Brion Salter, Cecilia H. McNicoll, and Wendel J. Hann Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project: Scientific Assessment Thomas M. -

Regional Conservation Partnership Program Investing in Idaho

Regional Conservation Partnership Program Investing in Idaho Regional Conservation Partnership Program Created by the 2014 Farm Bill, the Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) is a partner- Idaho Projects to driven, locally-led approach to conservation. It offers new opportunities for USDA’s Natural Resources Date Conservation Service (NRCS) to harness innovation, welcome new partners to the conservation mission, and demonstrates the value and efficacy of voluntary, private lands conservation. Projects by Resource Concern In 2017, NRCS is investing up to $225 million in 88 projects that impact nearly every state in the nation, including three in Idaho. Since 2014, NRCS has invested more than $825 million in 286 high- 3 3 impact projects, bringing together more than 2,000 conservation partners who have invested an additional $1.4 billion. By 2018, NRCS and partners will have invested at least $2.4 billion. These projects are leading to cleaner and more abundant water, better soil and air quality, enhance wildlife habitat, more resilient and productive agricultural lands and stronger rural economies. 4 Water Quantity/Drought Water Quality Wildlife Habitat 10 Projects $26.3 million NRCS Investment 93 Partners Idaho RCPP Projects Existing RCPP Projects Year Title Funding Lead Partner Number of NRCS Pool Partners Investment 2016 Farmer's Cooperative Ditch Company Project State Farmer’s Cooperative Ditch 7 $500,000 Company 2016 Greater Spokane River Watershed National Spokane Conservation 21 $7.7 million Implementation District 2016 -

High Desert Region Around Bend, Oregon by Lee Foster

High Desert Region Around Bend, Oregon by Lee Foster Beauty of nature in an alpine setting and diverse outdoor sports attract visitors to the Bend region of Central Oregon. Perusing natural beauty is the most universal pleasure here. Snow-capped mountains, pristine lakes, white-water rivers, and pine forests abound. At any time, the wilderness scenery is striking, with one of the dominant peaks, Mt. Bachelor, Broken Top, and the Sisters, usually present on your horizon. The main natural imprint on the land is a black volcanic presence. For the geology enthusiast, the Lava Lands Visitor Center explains the historic volcanic flows that form a stark legacy. Lava Butte is a 500-foot-high cinder cone, a silent reminder of past volcanic upheavals. A Rockhound Pow-Wow gathers amateur geologists here each July. Since opening in 1982, the High Desert Museum, south of Bend, has emerged as the most important nature interpretive effort in the state. (The High Desert Museum at Bend parallels Tucson’s Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum.) The raptor exhibit alone is worth the visit, putting you as close as you may ever get to a great horned owl, a red-tailed hawk, and an American kestrel. Foremost among the outdoor sports here is skiing at Mt. Bachelor. An extremely long ski season, both for alpine and nordic skiing, lasts into summer. The high- elevation chair lift to the top of Bachelor is popular also with non-skiers who seek an inspiring view of the region. In summer, hikers and campers depart from Bend for the nearby wilderness areas. -

Influence of Water Temperature and Beaver Ponds on Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in a High-Desert Stream, Southeastern Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Andrew G. Talabere for the degree of Master of Science in Fisheries Science presented on November 21. 2002. Title: Influence of Water Temperature and Beaver Ponds on Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in a High-Desert Stream, Southeastern Oregon Abstract approved Redacted for Privacy Redacted for Privacy The distribution of Lahontan cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi was assessed in a high-desert stream in southeastern Oregon where beaver Castor canadensis are abundant. Longitudinal patterns of beaver ponds, habitat, temperature, and Lahontan cutthroat trout age group distribution were identified throughout Willow Creek. Three distinct stream segments were classified based on geomorphological characteristics. Four beaver-pond and four free-flowing sample sections were randomly located in each of the three stream segments. Beavers substantially altered the physical habitat of Willow Creek increasing the depth and width of available habitat. In contrast, there was no measurable effect on water temperature. The total number of Lahontan cutthroat trout per meter was significantly higher in beaver ponds than free-flowing sections. Although density (fish! m2) showed no statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase, values in beaver pondswere two-fold those of free-flowing sections. Age- 1 and young-of-the-year trout were absent or in very low numbers in lower Willow Creek because of elevated temperatures, but high numbers of age-2 and 3 (adults) Lahontan cutthroat trout were found in beaver ponds where water temperatures reached lethal levels (>24°C). Apparently survival is greater in beaver ponds than free-flowing sections as temperatures approach lethal limits. Influence of Water Temperature and Beaver Ponds on Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in a High- Desert Stream, Southeastern Oregon by Andrew G. -

Central Oregon High Desert Tour 2019 Final 2

HeartCycle Bicycle Touring Club Central Oregon High Desert Tour Dates: Assemble in Sisters on June 10; Riding days June 11-16; depart June 17 Leaders: Ann Werner & Bill Buckley SAGs: Gail Buckley & Polly Page Miles: 288 miles, 13,670 ft climbing (can increase climbing) Rating: Int/Adv Riders: 28 Price: Total $ 1695 (Double occupancy), $400 at Registration, balance due by March 1, 2019. Single supplement fee $850. Overview Central Oregon, on the east side of the Cascade Mountains, is famed for its sunny, dry weather. It is big blue-sky country featuring snowcapped volcanoes, red barked ponderosa pine forests, high desert sage steppe, expansive lava fields and crystal clear mountain lakes. For those who live by mountain ranges, the solitary peaks of the volcanos are remarkable. The tour has two bases: Sunriver Resort and Sisters. Sunriver is a 4 Diamond Resort ten miles south of Bend where we will have a free day. The rooms are close to the Lodge and Village, which makes it easy for dining, canoeing, rafting, golf and enjoying the pool. Sunriver Golf Course Sisters is named after the Three Sisters mountains near it. The town is a charming western themed town of 2,000 with a pleasant ambience for hanging out after a ride – dining, brew, coffee & shopping. The Ponderosa Best Western has oversized rooms and is ideally located for riding and enjoying the town. The rides average 60 miles with most rides out and back. The rides are on Oregon Scenic Byways or Bikeways. Some have extended climbs of 2,500 but at a reasonable grade. -

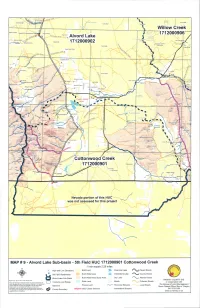

Alvord Lake Toerswnq Ihitk-Ul,.N Itj:Lnir

RtflOP' nt T37S Rt3F T37SR36E T37S R3275E 137S R34E TITStSE BloW Pour Willow Creek Babes Canyor Relds BIM Adrnirtistrative SiteFjel NeSs Airstrip / 41 171 2000906 Alvord Lake tOerswnq ihiTk-ul,.n itj:Lnir. Inokoul hluutte\ McDade Ranch 1712000902 I cvwr Twin Hot Spn Os Wilhlants Canyon , ,AEyy.4N seiralNo WARM APRI '738SR37E rIBS R3BE R38E Lower Roux Place err hlomo * / Oaterkirk Rartch - S., Rabbit HOe Mine 7,g.hit 0 Ptace '0 Arstnp 0 0 Ainord Vafley Lavy1ronrb P -o Rriaia .....c I herbbrrr RarrCh C _: 9S R34E Trout Creek CAhn '5- T39S R36E N Oleacireen Place T395 R37F Cruallu Canyon -1 Oleachea Pass T39S R38E \ Stergett Cabot Trout Creek Ranch ty Silvey Adrian Place' Wee Pole Canyon C SPRiNG, WHITEHORSE RANCH LN Pueblo Valley 4040 S Center Ridg Will, reek Pt cLean Cabin orgejadowo Gob 0810 WEIi Reynolds Ranch Owens Randr / I p labor Mocntai /1 °ueblo Mountain A'ir.STWLL Neil Pei S 'i-nWt Mahogany Ri.ge ,haaesot, uSGi, Pee: enn;s *i;i train ' 6868 4 n*a.asay Holloway T4OS R34E T4OS R35E I 1405 6E T405 R37E 'I 14'R38E / i.l:irintoi "Van Hone Basin' Colony Ranch 0 U Lithe Windy Pass z SChrERRYSPR1N. 0 I 1* RO4 - - 'r Denio Basin A' tuitdIhSPIhlNn% ()Conne eme Cottonwood Creek ie;. r' Gller Cabin T4IS R37E L,aticw P ',ik 1712000901 Grassy Basin BLAiRO tih'dlM P4 IS R34E Ago 141S R36E Lung Canyon Ii Middle Canyon Oecio Cemetery East B. ring Corral Canyon ento Nevada portion of this HUC was not assessed for this project MAP # 9 - Alvord Lake Sub-basin - 5th Field HUC 1712000901 Cottonwood Creek 1 inch equals 2.25 miles High and Low Elevations BLM Land Perennial Lake Paved Roads 5th Field Watersheds BLM Wilderness - Intermittent Lake County Roads S Alvord Lake Sub-Basin BLM Wilderness Study Area Dry Lake Arterial Roads HARNEY COUNTY GIS Prnpaeod by: Bryca Mcrnz Dare: Momlu 2006 State Land Marsh "_. -

Steens Mountain Recreation Lands Oregon

Steens Mountain Outdoor Manners Keep a clean camp. Leave the land cleaner than Recreation you found it. Lands Deposit all trash and litter in covered garbage can. Better yet, pack it out. Sink water may be drained at developed sites, but toilet holding Oregon tanks must be emptied at a commercial facility. Bring cooking fuel with you; cut no trees. Protect public and private property and report vandals. Drive only on the roads so as not to leave ruts or damage fragile vegetation. Keep Oregon Green. Use your ashtray. Build fires only in designated areas. Report uncon trolled fires to BLM's Fire Control Office in Burns, phone 573-7208 or 573-7209. Observe Oregon state hunting, fishing, and wildlife protection laws. Handle firearms safely. Enjoy and photograph petroglyphs and Indian artifacts, but leave them as they are. It is illegal to disturb them. Camp only in designated sites (see other side). Avoid rockrolling on the east face. It disturbs bighorns and may be dangerous to hikers and livestock in the gorges below. A waterfall at the head of Little Blitzen River Fishing the Donner und Blitzen Autumn color in Big Indian Gorge The Recreation Lands (refer to legend on map to cover painting), accessible only by foot, is stocked Aspen Belt—between 6,500 and 8,000 feet. This Be prepared before backpacking or hiking. Tell a (b) The entire Steens Mountain Loop Road is Steens Mountain delineate) consist of 147, 773 acres under the care Grazing Controlled with Lahontan cutthroat trout, an endangered includes groves of quaking aspen, small meadows, responsible person your destination and expected open approximately July 1 through October of the Bureau of Land Management, 41,577 acres species. -

Walking the High Desert

Journal of Geography ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjog20 Walking the High Desert: Encounters With Rural America Along the Oregon Desert Trail, by Ellen Waterston Seattle, University of Washington Press, 2020, 248 pp., 5.5 × 8.5 in, 1 map, ISBN: 9780295747507 John Harrington Jr. To cite this article: John Harrington Jr. (2020): Walking the High Desert: Encounters With Rural America Along the Oregon Desert Trail, by Ellen Waterston, Journal of Geography To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2020.1853795 Published online: 09 Dec 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjog20 JOURNAL OF GEOGRAPHY BOOK REVIEW Walking the High Desert: Encounters With Rural America Along the Oregon Desert Trail, by Ellen Waterston, Seattle, University of Washington Press, 2020, 248 pp., 5.5 Â 8.5 in, 1 map, ISBN: 9780295747507 Rarely does a hiking trail guidebook suggest that readers will Google Maps to gain a clear sky satellite view of the natural be channeling their “inner Carlos Castaneda” (6). In landmarks, vegetation cover, and human settlements men- Walking the High Desert, environmental humanist Ellen tioned along sections of the trail. Waterston provides an engaging commentary on many Writing about a desert environment frequently gets an aspects of life and land in southeastern Oregon. The book’s author discussing the availability of water. The resource is of subtitle, Encounters With Rural America Along the Oregon considerable importance for those who scrape out a liveli- Desert Trail, helps orient the reader toward a discussion of hood in the area. -

Oregon High Desert Classics 2021 Sponsorships

OREGON HIGH DESERT CLASSICS 2021 SPONSORSHIPS BENEFITING J BAR J YOUTH SERVICES The J Bar J Youth Services Oregon High Desert Classics (OHDC) is a Hunter/Jumper competition hosted in beautiful Bend, Oregon. Approved by the US Hunter Jumper Association as a National Horse Show with an A-rating from the US Equestrian Foundation this show is one of only 25 to receive Heritage Horse Show designation. Each year exhibitors, trainers, and barns from all over the Western United States and Canada gather on our 40 acre ranch; one of the last remaining grass footing rings in the country. We host 600 horses on property as well as 1000 exhibitors who compete for prizes and cash in our 2 week competition. Thou- sands of family, spectators, vendors, and staff join them, celebrating the athleticism of the horses and riders, as well as enjoying the variety of food and shopping options offered at the vendor booths in the Village Green. The businesses and foundations who support this incredible event are not only bringing a world class horse show to Central Oregon but also helping facilitate change for youth in jeopardy. This is the only show of its caliber which is primarily a fundraiser, benefitting J Bar J Youth Services, a 501(c)(3) non-profit. Oregon High Desert Classics 2021 2 ww.oregonhighdesertclassics.org WHY SPONSOR? Association with one of the most prestigious show jumping competitions in the Northwest. Funds raised support at-risk youth programs focused on prevention, intervention, education, treatment and accountability. Gain exposure with an important market group: - Oregon High Desert Classics attract business leaders, socialites, vendors, exhibitors, and trainers from Oregon, Washington, Wyoming, Idaho, Montana, California, Nevada, Arizona, British Co- lumbia and Alberta.