Dtpg 17 2010.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Italian Democracy

Bulletin of Italian Politics Vol. 1, No. 1, 2009, 29-47 The Transformation of Italian Democracy Sergio Fabbrini University of Trento Abstract: The history of post-Second World War Italy may be divided into two distinct periods corresponding to two different modes of democratic functioning. During the period from 1948 to 1993 (commonly referred to as the First Republic), Italy was a consensual democracy; whereas the system (commonly referred to as the Second Republic) that emerged from the dramatic changes brought about by the end of the Cold War functions according to the logic of competitive democracy. The transformation of Italy’s political system has thus been significant. However, there remain important hurdles on the road to a coherent institutionalisation of the competitive model. The article reconstructs the transformation of Italian democracy, highlighting the socio-economic and institutional barriers that continue to obstruct a competitive outcome. Keywords: Italian politics, Models of democracy, Parliamentary government, Party system, Interest groups, Political change. Introduction As a result of the parliamentary elections of 13-14 April 2008, the Italian party system now ranks amongst the least fragmented in Europe. Only four party groups are represented in the Senate and five in the Chamber of Deputies. In comparison, in Spain there are nine party groups in the Congreso de los Diputados and six in the Senado; in France, four in the Assemblée Nationale an d six in the Sénat; and in Germany, six in the Bundestag. Admittedly, as is the case for the United Kingdom, rather fewer parties matter in those democracies in terms of the formation of governments: generally not more than two or three. -

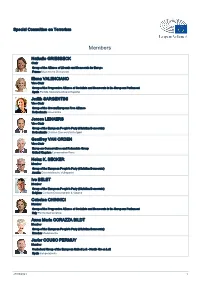

List of Members

Special Committee on Terrorism Members Nathalie GRIESBECK Chair Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe France Mouvement Démocrate Elena VALENCIANO Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Spain Partido Socialista Obrero Español Judith SARGENTINI Vice-Chair Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Netherlands GroenLinks Jeroen LENAERS Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Netherlands Christen Democratisch Appèl Geoffrey VAN ORDEN Vice-Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group United Kingdom Conservative Party Heinz K. BECKER Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Austria Österreichische Volkspartei Ivo BELET Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Belgium Christen-Democratisch & Vlaams Caterina CHINNICI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Anna Maria CORAZZA BILDT Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Sweden Moderaterna Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente 27/09/2021 1 Edward CZESAK Member European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) France Les Républicains Gérard DEPREZ Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Belgium Mouvement Réformateur Agustín -

Remaking Italy? Place Configurations and Italian Electoral Politics Under the ‘Second Republic’

Modern Italy Vol. 12, No. 1, February 2007, pp. 17–38 Remaking Italy? Place Configurations and Italian Electoral Politics under the ‘Second Republic’ John Agnew The Italian Second Republic was meant to have led to a bipolar polity with alternation in national government between conservative and progressive blocs. Such a system it has been claimed would undermine the geographical structure of electoral politics that contributed to party system immobilism in the past. However, in this article I argue that dynamic place configurations are central to how the ‘new’ Italian politics is being constructed. The dominant emphasis on either television or the emergence of ‘politics without territory’ has obscured the importance of this geographical restructuring. New dynamic place configurations are apparent particularly in the South which has emerged as a zone of competition between the main party coalitions and a nationally more fragmented geographical pattern of electoral outcomes. These patterns in turn reflect differential trends in support for party positions on governmental centralization and devolution, geographical patterns of local economic development, and the re-emergence of the North–South divide as a focus for ideological and policy differences between parties and social groups across Italy. Introduction One of the high hopes of the early 1990s in Italy was that following the cleansing of the corruption associated with the party regime of the Cold War period, Italy could become a ‘normal country’ in which bipolar politics of electoral competition between clearly defined coalitions formed before elections, rather than perpetual domination by the political centre, would lead to potential alternation of progressive and conservative forces in national political office and would check the systematic corruption of partitocrazia based on the jockeying for government offices (and associated powers) after elections (Gundle & Parker 1996). -

INDIRIZZI a CUI SCRIVERE Governo

INDIRIZZI A CUI SCRIVERE Governo Presidente del Enrico Letta [email protected] Palazzo Chigi Consiglio tel. 06 6779 3250 - [email protected] Piazza Colonna 370 fax 06 6779 3543 00187 Roma Vice Presidente e Angelino Alfano [email protected] Ministro dell'interno Ufficio del Segretario Anna Lucia Esposito [email protected] Palazzo Chigi generale tel. 06 6779 3206 Piazza Colonna 370 fax. 06 6795807 00187 Roma Vicario Ufficio di Dott.ssa Mara [email protected] Palazzo Chigi Segreteria generale SPATUZZI Piazza Colonna 370 tel. 06 67793206 00187 Roma fax. 06 6795807 Il Segretario Generale Manlio STRANO [email protected] Palazzo Chigi della Presidenza del Capo della Segreteria particolare Piazza Colonna 370 Consiglio dei Ministri Tel 06 6779 3250 del Presidente del Consiglio – 00187 Roma fax 06 6779 3543 Sottosegretario alla Antonio Catricalà [email protected] Presidenza del C.M. tel. 06 67793640 – fax 06 6797428 Sottosegretario alla Marco Minniti [email protected] Palazzo Chigi – Presidenza del Piazza Colonna, 370 – 00187 Roma Consiglio dei Ministri) Sottosegretario al Filippo Patroni Griffi Palazzo Chigi – consiglio dei ministri Piazza Colonna, 370 – 00187 Roma Ufficio di segreteria del Consiglio dei Ministri Ufficio Stampa del tel. 06 6779 3050 – [email protected] Portavoce fax 06 6798648 Lupi Segreteria del Ministro [email protected] Capo della Segreteria del Ministro: Dott. Emmanuele Forlani [email protected] Segretario particolare del Ministro: On. Marcello Di Caterina -

1 Populism in Election Times: a Comparative Analysis Of

POPULISM IN ELECTION TIMES: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF ELEVEN COUNTRIES IN WESTERN EUROPE Laurent Bernharda and Hanspeter Kriesib,c aSwiss Centre of Expertise in the Social Sciences (FORS), University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland; bDepartment of Political and Social Sciences, European University Institute, San Domenico di Fiesole (Florence), Italy; cLaboratory for Comparative Social Research, National Research University Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russian Federation CONTACT: Laurent Bernhard [email protected] ABSTRACT: The article comparatively examines the levels of populism exhibited by parties in Western Europe. It relies on a quantitative content analysis of press releases collected in the context of eleven national elections between 2012 to 2015. In line with the first hypothesis, the results show that parties from both the radical right and the radical left make use of populist appeals more frequently than mainstream parties. With regard to populism on cultural issues, the article establishes that the radical right outclasses the remaining parties, thereby supporting the second hypothesis. On economic issues, both types of radical parties are shown to be particularly populist. This pattern counters the third hypothesis, which suggests that economic populism is most prevalent among the radical left. Finally, there is no evidence for the fourth hypothesis, given that parties from the South do not resort to more populism on economic issues than those from the North. KEYWORDS: Introduction In the first decades immediately following World War II, populism was a rather marginal phenomenon in Western Europe (Gellner and Ionescu 1969). In contrast to many other regions, conventional wisdom had long maintained that populism would have a hard time establishing itself in this part of the world (Priester 2012: 11). -

Italie / Italy

ITALIE / ITALY LEGA (LIGUE – LEAGUE) Circonscription nord-ouest 1. Salvini Matteo 11. Molteni Laura 2. Andreina Heidi Monica 12. Panza Alessandro 3. Campomenosi Marco 13. Poggio Vittoria 4. Cappellari Alessandra 14. Porro Cristina 5. Casiraghi Marta 15. Racca Marco 6. Cattaneo Dante 16. Sammaritani Paolo 7. Ciocca Angelo 17. Sardone Silvia Serafina (eurodeputato uscente) 18. Tovaglieri Isabella 8. Gancia Gianna 19. Zambelli Stefania 9. Lancini Danilo Oscar 20. Zanni Marco (eurodeputato uscente) (eurodeputato uscente) 10. Marrapodi Pietro Antonio Circonscription nord-est 1. Salvini Matteo 8. Dreosto Marco 2. Basso Alessandra 9. Gazzini Matteo 3. Bizzotto Mara 10. Ghidoni Paola (eurodeputato uscente) 11. Ghilardelli Manuel 4. Borchia Paolo 12. Lizzi Elena 5. Cipriani Vallì 13. Occhi Emiliano 6. Conte Rosanna 14. Padovani Gabriele 7. Da Re Gianantonio detto Toni 15. Rento Ilenia Circonscription centre 1. Salvini Matteo 9. Pastorelli Stefano 2. Baldassarre Simona Renata 10. Pavoncello Angelo 3. Adinolfi Matteo 11. Peppucci Francesca 4. Alberti Jacopo 12. Regimenti Luisa 5. Bollettini Leo 13. Rinaldi Antonio Maria 6. Bonfrisco Anna detta Cinzia 14. Rossi Maria Veronica 7. Ceccardi Susanna 15. Vizzotto Elena 8. Lucentini Mauro Circonscription sud 1. Salvini Matteo 10. Lella Antonella 2. Antelmi Ilaria 11. Petroni Luigi Antonio 3. Calderano Daniela 12. Porpiglia Francesca Anastasia 4. Caroppo Andrea 13. Sapignoli Simona 5. Casanova Massimo 14. Sgro Nadia 6. Cerrelli Giancarlo 15. Sofo Vincenzo 7. D’Aloisio Antonello 16. Staine Emma 8. De Blasis Elisabetta 17. Tommasetti Aurelio 9. Grant Valentino 18. Vuolo Lucia Circonscription insulaire 1. Salvini Matteo 5. Hopps Maria Concetta detta Marico 2. Donato Francesca 6. Pilli Sonia 3. -

ITALIA COMENTARIO GENERAL Situación Política Y Económica En

23 ITALIA COMENTARIO GENERAL Situación política y económica En marzo, el proceso de elección de las candidaturas para las elecciones municipales que se celebrarán en junio en algunas de las principales ciudades italianas ha elevado de nuevo la tensión en la situación política italiana, producida por los enfrentamientos entre los partidos y en algunos casos, como en el Partido Democrático, dentro de ellos. A finales del mes de marzo aún no se tenía decididas todas las candidaturas. Las elecciones se celebrarán en 1.359 ayuntamientos incluyendo 26 capitales de provincia entre las que se encuentran Bolonia, Cagliari, Milán, Nápoles, Roma, Turín y Trieste. También se votarán los nuevos titulares de la alcaldía en 27 nuevos municipios que se han creado en 2016 mediante procesos de integración administrativa tras la última reforma de las provincias que ha entrado en vigor este año. A pesar de los intentos de acercamiento producidos en los últimos meses entre Forza Italia, de Silvio Berlusconi, y la Liga Norte, de Mateo Salvini, el centro derecha no se ha puesto de acuerdo en la presentación de una candidatura común en las alcaldías de Roma y Turín. En el caso de Roma, junto a estos dos partidos, también estaba prevista la participación del partido liderado por Giorgia Meloni, Hermanos de Italia, en la presentación de una candidatura unida del centro derecha para conseguir vencer al Partido Democrático. Los acuerdos no se han podido alcanzar y a mediados de mes, Giorgia Meloni anunciaba que ella misma se presentaba a la alcaldía. Meloni cuenta con el apoyo de la Liga Norte de Matteo Salvini pero Silvio Berlusoni y su partido, Forza Italia, siguen apoyando a su favorito, Guido Bertolaso, que fue Director de Protección Civil. -

Governo Berlusconi Iv Ministri E Sottosegretari Di

GOVERNO BERLUSCONI IV MINISTRI E SOTTOSEGRETARI DI STATO MINISTRI CON PORTAFOGLIO Franco Frattini, ministero degli Affari Esteri Roberto Maroni, ministero dell’Interno Angelino Alfano, ministero della Giustizia Giulio Tremonti, ministero dell’Economia e Finanze Claudio Scajola, ministero dello Sviluppo Economico Mariastella Gelmini, ministero dell’Istruzione Università e Ricerca Maurizio Sacconi, ministero del Lavoro, Salute e Politiche sociali Ignazio La Russa, ministero della Difesa; Luca Zaia, ministero delle Politiche Agricole, e Forestali Stefania Prestigiacomo, ministero dell’Ambiente, Tutela Territorio e Mare Altero Matteoli, ministero delle Infrastrutture e Trasporti Sandro Bondi, ministero dei Beni e Attività Culturali MINISTRI SENZA PORTAFOGLIO Raffaele Fitto, ministro per i Rapporti con le Regioni Gianfranco Rotondi, ministro per l’Attuazione del Programma Renato Brunetta, ministro per la Pubblica amministrazione e l'Innovazione Mara Carfagna, ministro per le Pari opportunità Andrea Ronchi, ministro per le Politiche Comunitarie Elio Vito, ministro per i Rapporti con il Parlamento Umberto Bossi, ministro per le Riforme per il Federalismo Giorgia Meloni, ministro per le Politiche per i Giovani Roberto Calderoli, ministro per la Semplificazione Normativa SOTTOSEGRETARI DI STATO Gianni Letta, sottosegretario di Stato alla Presidenza del Consiglio dei ministri, con le funzioni di segretario del Consiglio medesimo PRESIDENZA DEL CONSIGLIO DEI MINISTRI Maurizio Balocchi, Semplificazione normativa Paolo Bonaiuti, Editoria Michela Vittoria -

Download Clinton Email June Release

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2014-20439 Doc No. C05761507 Date: 06/30/2015 RELEASE IN PART B6 From: H <[email protected]> Sent: Tuesday, December 15, 2009 12:25 PM To: '[email protected]' Subject: Fw: H: Memo, idea on Berlusconi attack. Sid Attachments: hrc memo berlusconi 121509.docx Pls print. Original Message From: sbwhoeop To: H Sent: Tue Dec 15 10:43:11 2009 Subject: H: Memo, idea on Berlusconi attack. Sid CONFIDENTIAL December 15, 2009 For: Hillary From: Sid Re: The Berlusconi assault 1. The physical attack on Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi is a major political event in Italy and Europe. His assailant is a mentally disturbed man without a political agenda who has been in and out of psychiatric care since he was 18 years old. Nonetheless, the assault has significant repercussions. It has generated sympathy for Berlusconi as a victim—he has been obviously injured, lost two teeth and a pint of blood, and doctors will keep him in the hospital for perhaps a week for observation. The attack comes as Berlusconi was beginning to lose political footing, having lost his legal immunity. One court inquiry is turning up evidence of his links to the Mafia while another is examining his role in the bribery case of British lawyer David Mills. Berlusconi's government and party have used the attack as a way to turn the sudden sympathy for him to his advantage, claiming that his opponents have sown a climate of "hate." Through demogogic appeals they are attempting to discredit and rebuff the legal proceedings against him and undermine the investigative press. -

La Politica Estera Dell'italia. Testi E Documenti

AVVERTENZA La dottoressa Giorgetta Troiano, Capo della Sezione Biblioteca e Documentazione dell’Unità per la Documentazione Storico-Diplomatica e gli Archivi ha selezionato il materiale, redatto il testo e preparato gli indici del presente volume con la collaborazione della dott.ssa Manuela Taliento, del dott. Fabrizio Federici e del dott. Michele Abbate. MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI UNITÀ PER LA DOCUMENTAZIONE STORICO-DIPLOMATICA E GLI ARCHIVI 2005 LA POLITICA ESTERA DELL’ITALIA TESTI E DOCUMENTI ROMA Roma, 2009 - Stilgrafica srl - Via Ignazio Pettinengo, 31/33 - 00159 Roma - Tel. 0643588200 INDICE - SOMMARIO III–COMPOSIZIONE DEI GOVERNI . Pag. 3 –AMMINISTRAZIONE CENTRALE DEL MINISTERO DEGLI AFFARI ESTERI . »11 –CRONOLOGIA DEI PRINCIPALI AVVENIMENTI CONCERNENTI L’ITALIA . »13 III – DISCORSI DI POLITICA ESTERA . » 207 – Comunicazioni del Ministro degli Esteri on. Fini alla Com- missione Affari Esteri del Senato sulla riforma dell’ONU (26 gennaio) . » 209 – Intervento del Ministro degli Esteri Gianfranco Fini alla Ca- mera dei Deputati sulla liberazione della giornalista Giulia- na Sgrena (8 marzo) . » 223 – Intervento del Ministro degli Esteri on. Fini al Senato per l’approvazione definitiva del Trattato costituzionale euro- peo (6 aprile) . » 232 – Intervento del Presidente del Consiglio, on. Silvio Berlusco- ni alla Camera dei Deputati (26 aprile) . » 235 – Intervento del Presidente del Consiglio on. Silvio Berlusco- ni al Senato (5 maggio) . » 240 – Messaggio del Presidente della Repubblica Ciampi ai Paesi Fondatori dell’Unione Europea (Roma, 11 maggio) . » 245 – Dichiarazione del Ministro degli Esteri Fini sulla lettera del Presidente Ciampi ai Capi di Stato dei Paesi fondatori del- l’UE (Roma, 11 maggio) . » 247 – Discorso del Ministro degli Esteri Fini in occasione del Cin- quantesimo anniversario della Conferenza di Messina (Messina, 7 giugno) . -

The Political Legacy of Entertainment TV

School of Economics and Finance The Political Legacy of Entertainment TV Ruben Durante, Paolo Pinotti and Andrea Tesei Working Paper No. 762 December 201 5 ISSN 1473-0278 The Political Legacy of Entertainment TV∗ Ruben Durantey Paolo Pinottiz Andrea Teseix July 2015 Abstract We investigate the political impact of entertainment television in Italy over the past thirty years by exploiting the staggered intro- duction of Silvio Berlusconi's commercial TV network, Mediaset, in the early 1980s. We find that individuals in municipalities that had access to Mediaset prior to 1985 - when the network only featured light entertainment programs - were significantly more likely to vote for Berlusconi's party in 1994, when he first ran for office. This effect persists for almost two decades and five elections, and is es- pecially pronounced for heavy TV viewers, namely the very young and the old. We relate the extreme persistence of the effect to the relative incidence of these age groups in the voting population, and explore different mechanisms through which early exposure to en- tertainment content may have influenced their political attitudes. Keywords: television, entertainment, voting, political participa- tion, Italy. JEL codes: L82, D72, Z13 ∗We thank Alberto Alesina, Antonio Ciccone, Filipe Campante, Ruben Enikolopov, Greg Huber, Brian Knight, Valentino Larcinese, Marco Manacorda, Torsten Persson, Barbara Petrongolo, Andrei Shleifer, Francesco Sobbrio, Joachim Voth, David Weil, Katia Zhuravskaya, and seminar participants at Bocconi, CREI, NYU, MIT, Sciences Po, Brown, Dartmouth, Sorbonne, WZB, Surrey, Queen Mary, Yale, EIEF, LSE, Namur, and participants at the 2013 AEA Meeting, the 2013 EUI Conference on Communica- tions and Media Markets, and the Lisbon Meeting on Institutions and Political Economy for helpful comments. -

Archivio Storico Della Presidenza Della Repubblica

ARCHIVIO STORICO DELLA PRESIDENZA DELLA REPUBBLICA Ufficio per la stampa e l’informazione Archivio fotografico del Presidente della Repubblica Oscar Luigi Scalfaro (1992-1999) settembre 2006 2 Il lavoro è a cura di Manuela Cacioli. 3 busta evento data PROVINI 1 Roma. Deposizione di corona d’alloro all’Altare della Patria e 1992 mag. 27-ago. 7 incontro col sindaco Franco Carraro a Piazza Venezia, \27.5.92. Presentazione dei capi missione accreditati e delle loro consorti e Festa nazionale della Repubblica, \7.6.92. “La Famiglia Legnanese” per il 40° anniversario di fondazione, \2.7.92. Redazione della rivista “Nuova Ecologia”, \13.7.92 (n.4). Avv. Paolo Del Bufalo e gruppo di giovani romani, \20.7.92. Confederazione italiana fra Associazioni combattentistiche italiane, \28.7.92. Gen. Roberto Occorsio e amm. Luciano Monego in visita di congedo, \28.7.92. Yahya Mahmassani, nuovo ambasciatore del Libano, e Patrick Stanislaus Fairweather, nuovo ambasciatore di Gran Bretagna: presentazione lettere credenziali, \29.7.92. Alì Akbar Velayati, ministro degli esteri dell’Iran, \29.7.92. Madre Teresa di Calcutta, \31.7.92. On. Giuseppe Vedovato, Associazione ex parlamentari della Repubblica, \31.7.92. Avv. Carlo D’Amelio, Associazione nazionale avvocati pensionati, \31.7.92. Giuramento dell’on. Emilio Colombo, ministro degli esteri del governo Amato, \1.8.92. On. prof. Salvatore Andò, ministro della difesa, il capo di Stato maggiore dell’aeronautica e componenti della pattuglia acrobatica nazionale, \5.8.92. Il piccolo Farouk Kassam e i genitori, \7.8.92. 2 On. Carlo Casini con i vincitori del concorso nazionale “La famiglia: 1992 giu.