NWU Guide to Book Contracts: Appendix a Focus on Academic Press Contracts 2010 Ken Wachsberger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library Friends News Stevens Memorial Library, North Andover, Mass

Library Friends News Stevens Memorial Library, North Andover, Mass. Spring 2003 Local Historian/Author at Spring 2003 Book Sale will Library for Book Signing be a Browser’s Delight The Friends will host Kathleen Dalton, Andover Thousands of excellent books of every kind to be resident and author of Theodore Roosevelt: A offered at unbelievably low prices. Strenuous Life, on May 7 at 7 p.m. at the library. The Friends of the Library Semi-Annual Booksale is Critics are lauding Kathleen Dalton’s Theodore the weekend of May 17th 9-5 & May 18th 2-5 with a Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life, published by Alfred A. special member’s preview on Friday, May 16th 5-7pm. Knopf in October. Lucky for us, Dalton is Cecil F. P. Bancroft Instructor of The Fall Book Sale 2002 raised more than $4,200! This history and social science at Phillips Academy and money will directly support the library. Our deepest lives in Andover with her husband, the historian E. thanks go to Star Market who provided us with plastic Anthony Rotundo and their two children. bags for purchases and the Buck a Bag Sunday. Issues Dalton deals with include homeland security during WWI; corporate greed in TR’s time and our own; Volunteers needed and the influence of the suffragist movement. The book sale’s success relies on volunteers. There are four ways you can help ensure this book sale is From the book jacket: “Both an updated political interpretation and an intimate personal story of a loving the most successful ever. but difficult man, his wife, his family, and his loyal First, give your personal library a thorough spring friends, [the book] will change persuasively the way we cleaning. -

Market Power in the Academic Publishing Industry

Market Power in the Academic Publishing Industry What is an Academic Journal? • A serial publication containing recent academic papers in a certain field. • The main method for communicating the results of recent research in the academic community. Why is Market Power important to think about? • Commercial academic journal publishers use market power to artificially inflate subscription prices. • This practice drains the resources of libraries, to the detriment of the public. How Does Academic Publishing Work? • Author writes paper and submits to journal. • Paper is evaluated by peer reviewers (other researchers in the field). • If accepted, the paper is published. • Libraries pay for subscriptions to the journal. The market does not serve the interests of the public • Universities are forced to “double-pay”. 1. The university funds research 2. The results of the research are given away for free to journal publishers 3. The university library must pay to get the research back in the form of journals Subscription Prices are Outrageous • The highest-priced journals are those in the fields of science, technology, and medicine (or STM fields). • Since 1985, the average price of a journal has risen more than 215 percent—four times the average rate of inflation. • This rise in prices, combined with the CA budget crisis, has caused UC Berkeley’s library to cancel many subscriptions, threatening the library’s reputation. A Comparison Why are prices so high? Commercial publishers use market power to charge inflated prices. Why do commercial publishers have market power? • They control the most prestigious, high- quality journals in many fields. • Demand is highly inelastic for high-quality journals. -

Mapping the Future of Scholarly Publishing

THE OPEN SCIENCE INITIATIVE WORKING GROUP Mapping the Future of Scholarly Publishing The Open Science Initiative (OSI) is a working group convened by the National Science Communi- cation Institute (nSCI) in October 2014 to discuss the issues regarding improving open access for the betterment of science and to recommend possible solutions. The following document summa- rizes the wide range of issues, perspectives and recommendations from this group’s online conver- sation during November and December 2014 and January 2015. The 112 participants who signed up to participate in this conversation were drawn mostly from the academic, research, and library communities. Most of these 112 were not active in this conversa- tion, but a healthy diversity of key perspectives was still represented. Individual participants may not agree with all of the viewpoints described herein, but participants agree that this document reflects the spirit and content of the conversation. This main body of this document was written by Glenn Hampson and edited by Joyce Ogburn and Laura Ada Emmett. Additional editorial input was provided by many members of the OSI working group. Kathleen Shearer is the author of Annex 5, with editing by Dominque Bambini and Richard Poynder. CC-BY 2015 National Science Communication Institute (nSCI) www.nationalscience.org [email protected] nSCI is a US-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization First edition, January 2015 Final version, April 2015 Recommended citation: Open Science Initiative Working Group, Mapping the Future of Scholarly -

A Quick Guide to Scholarly Publishing

A QUICK GUIDE TO SCHOLARLY PUBLISHING GRADUATE WRITING CENTER • GRADUATE DIVISION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA • BERKELEY Belcher, Wendy Laura. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2009. Benson, Philippa J., and Susan C. Silver. What Editors Want: An Author’s Guide to Scientific Journal Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. Derricourt, Robin. An Author’s Guide to Scholarly Publishing. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. Germano, William. From Dissertation to Book. 2nd ed. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013. ———. Getting It Published: A Guide for Scholars and Anyone Else Serious about Serious Books. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016. Goldbort, Robert. Writing for Science. New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2006. Harman, Eleanor, Ian Montagnes, Siobhan McMenemy, and Chris Bucci, eds. The Thesis and the Book: A Guide for First- Time Academic Authors. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003. Harmon, Joseph E., and Alan G. Gross. The Craft of Scientific Communication. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. Huff, Anne Sigismund. Writing for Scholarly Publication. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1999. Luey, Beth. Handbook for Academic Authors. 5th ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Luey, Beth, ed. Revising Your Dissertation: Advice from Leading Editors. Updated ed. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. Matthews, Janice R., John M. Bowen, and Robert W. Matthews. Successful Scientific Writing: A Step-by-Step Guide for the Biological and Medical Sciences. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2008. Moxley, Joseph M. PUBLISH, Don’t Perish: The Scholar’s Guide to Academic Writing and Publishing. -

Publishing Brochure 2021

Publishing with Lekha Ink An Informational Packet for Authors LEKHA INK, CORP. ABOUT LEKHA INK Lekha: A Brief History Jyoti Yelagalawadi, an avid storyteller and writer since her youth, has always believed that children and youth can accomplish anything by using their imaginations. One of her life long dreams has been to bring unique and good quality books written for or by chil- dren. She started Lekha Publishers in 2002 when she saw the poems written by one of her friends, a volunteer in her neighborhood school. After noticing that no traditional pub- lishing company would publish this extremely unique book of poems, she researched and found out the best way to publish Richard Makenzie’s Poems From The Playground. After that she published Laugh With Dinosaurs and a couple of other books, that she had written, under the company’s banner. Jyoti started a writing program as an experiment in the summer of 2006, when a friend of Jyoti asked her to guide her daughter and a few other children in the art of writing. Jyoti's wonderful experience that summer inspired her to continue the writing center as a inseparable part of her independent publishing company, which was later incorporated as Lekha Ink, Corp. Since then she and her staff have guided and published over 5000 young authors in anthologies. She has personally guided 45 authors, both young authors and adults, in creating their own books. How Publishing with Lekha Works Lekha is a small, independent publishing house, and simply cannot afford to operate in the way of a tradi- tional publishing house, which covers all the initial costs, then pays the author a percentage of the book sales. -

Using Bibliometric Big Data to Analyze Faculty Research Productivity in Health Policy and Management Christopher A. Harle

Using Bibliometric Big Data to Analyze Faculty Research Productivity in Health Policy and Management Christopher A. Harle, PhD [corresponding author] Joshua R. Vest, PhD, MPH Nir Menachemi, PhD, MPH Department of Health Policy and Management, Richard M. Fairbanks School of Public Health, Indiana University 1050 Wishard Blvd. Indianapolis IN 46202-2872 PHONE: 317-274-5396 Keywords: big data, faculty productivity, bibliometrics, citation analysis ___________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Harle, C. A., Vest, J. R., & Menachemi, N. (2016). Using Bibliometric Big Data to Analyze Faculty Research Productivity in Health Policy and Management. The Journal of Health Administration Education; Arlington, 33(2), 285–293. ABSTRACT Bibliometric big data and social media tools provide new opportunities to aggregate and analyze researchers’ scholarly impact. The purpose of the current paper is to describe the process and results we obtained after aggregating a list of public Google Scholar profiles representing researchers in Health Policy and Management or closely-related disciplines. We extracted publication and citation data on 191 researchers who are affiliated with health administration programs in the U.S. With these data, we created a publicly available listing of faculty that includes each person’s name, affiliation, year of first citation, total citations, h-index and i-10 index. The median of total citations per individual faculty member was 700, while the maximum was 46,363. The median h-index was 13, while the maximum was 91. We plan to update these statistics and add new faculty to our public listing as new Google Scholar profiles are created by faculty members in the field. -

Penny C. Sansevieri

:gBglb]^kl@nb]^mhIn[eb\bsbg` Zg]FZkd^mbg`rhnk;hhd PENNY C. SANSEVIERI New York FROM BOOK TO BESTSELLER :gBglb]^kl@nb]^mhIn[eb\bsbg` Zg]FZkd^mbg`Rhnk;hhd by Penny C. Sansevieri © 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and record- ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from author or publisher (except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages and/or show brief video clips in a review). ISBN: 1-60037-088-8 (Hardcover) ISBN: 1-60037-085-3 (Paperback) ISBN: 1-60037-086-1 (eBook) ISBN: 1-60037-087-X (Audio) Published by: Morgan James Publishing, LLC 1225 Franklin Ave. Ste 325 Garden City, NY 11530-1693 Toll Free 800-485-4943 www.MorganJamesPublishing.com Interior Design by: Bonnie Bushman [email protected] MORE BOOKS BY PENNY C. SANSEVIERI GhgÛ\mbhg Get Published Today (Morgan James Publishing 2006) From Book to Bestseller (PublishingGold.com, Inc. 2005) No More Rejections: Get Published Today! (PublishingGold.com, Inc. 2005) No More Rejections: Get Published Today! ,QÀQLW\3XEOLVKLQJ Get Published! $QDXWKRU·VJXLGHWRWKH RQOLQHSXEOLVKLQJUHYROXWLRQ (1st Books, 2001) ?b\mbhg 7KH&OLIIKDQJHU (iUniverse, 2000) Candlewood Lake (iUniverse, 2006) To subscribe to our free newsletter send an e-mail to ln[l\kb[^9ZfZkd^mbg`^qi^km'\hf P^]eho^rhnk_^^][Z\d' A^k^lahpmh\hgmZ\mnl3 Author Marketing Experts, Inc. 3RVW2IÀFH%R[ San Diego, CA 92142 www.amarketingexpert.com [email protected] ?hk?kZgl The best dad a girl could ever have. -

Author and Illustrator Marketing Guidance from Publisher Lee German

Author and Illustrator Marketing Guidance from Publisher Lee German Contents: General introduction - promotional kit - resources What you can do - friends, family and associates - online presence - introduce yourself to the community Support the bookstores—they support you! Scheduling Events - book launch (includes minimum book launch requirements) - book signings - libraries - school visits - emails/phone calls Arbordale General Marketing and Promotional Plan - outline of production schedule We welcome, appreciate and need your help in making the book a success. When I talk to Baker & Taylor and Ingram buyers, they always ask about book signings and the media coverage surrounding new releases. They specifically want to know what author/illustrator events are planned (i.e., how serious is our marketing commitment) and then they stock their nearest warehouses to support anticipated demand from these events. I mention this because your involvement in the process is a critical marketing component. As publisher, we can push great books all day long, but the industry “scuttlebutt” is “no author involvement, no future.” We can see that in the sales of books—straight down the line. Our objective is to sell our books nationwide and soon, internationally, but to get started we absolutely depend on the local interest around author, illustrator, and publisher. The term is local buzz, and without that, it is very difficult to get momentum for a new release. Think of any classic children’s book—association with the author and illustrator is tight because they were engaged with their publisher and committed to helping the book sell. I know that this is children’s book promotion, and we all need to have fun! I find it personally rewarding to get involved in the publicity effort, and I hope that you will too. -

Independent Author Policy

THE TOWN BOOK STORE ~ Satisfying Book Lovers Since 1934 ~ 270 East Broad Street Westfield, NJ 07090 Phone: (908) 233-3535 Fax: (908) 654-8300 E-Mail: [email protected] Independent Author Policy Thank you for considering our bookstore for placement of your book. Because we are approached so many times each week by authors hoping we will sell their books, it has become necessary to develop a written policy so that all expectations are clear. Technology has made publishing easier, often without traditional professional editing, proofreading and evaluation of marketing and distribution. Consequently, the number of books we are asked to consider for our shelves has risen dramatically. No bookstore can carry every published title, whether from a major publisher’s list or self-published by a local author. Many factors influence a bookseller’s decision; of the most importance is whether the book will sell at this store to our customers. As with all books, when deciding whether or not to stock, we consider the subject, production quality, retail price and discount available from our sources. We are asked to review many books each year. We decline many books, including those by well-known and award-winning writers if we determine that they are not a good match for our store. We have only a limited amount of space and must devote that to books we feel will sell to our customers. It is never a pleasant task to decline when dealing directly with an author rather than simply reviewing a catalog. Due to the increasing volume of requests and the time involved to properly review books, it has become necessary for us to adopt the following policy. -

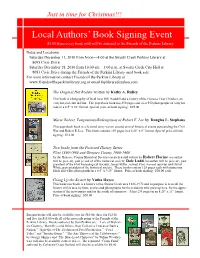

Local Authors' Book Signing Event

Just in time for Christmas!!! Local Authors’ Book Signing Event $1.00 from every book sold will be donated to the Friends of the Perkins Library Dates and Locations: Saturday December 11, 2010 from Noon—4:00 at the Swartz Creek Perkins Library at 8095 Civic Drive Saturday December 18, 2010 from 10:00 am—3:00 p.m. at Swartz Creek City Hall at 8083 Civic Drive during the Friends of the Perkins Library used book sale For more information contact Friends of the Perkins Library at www.friendsoftheperkinslibrary.org or email [email protected] The Original Hot Rodder written by Kathy A. Ridley This book is a biography of local racer Bill Waddill and a history of the Genesee Gear Grinders, an early hot rod club in Flint. The paperback book has 250 pages and over 550 photographs of early hot rods in a 8.5” x 10” format. Special price at book signing: $25.00 Marse Robert, Temptations/Redemptions of Robert E. Lee by Douglas L. Stephens This paperback book is a fictional story woven around several historical events surrounding the Civil War and Robert E. Lee. This book contains 169 pages in a 5.25” x 8” format. Special price at book signing: $14.00 Two books from the Postcard History Series Flint 1890-1960 and Genesee County 1900-1960 by the Genesee County Historical Society researched and written by Robert Florine (co-author will be present), past president of the historical society; Dale Ladd (co-author will be present), past president of the Flint Genealogical Society; James Miller, retired Flint Journal reporter and David White, past president of the historical society. -

Book Signing Tips

Antoinette Tuff Speaker – Survivor – Author – Community Safety Advocate CEO/Founder of Kids on the Move for Success BOOK SIGNING TIPS With these guidelines, approximately 200 people an hour can get their books signed: 1. Have a 6-foot table that is out of the way of the main traffic of the event. The speaker should be seated about in the middle of the table with space around for the books. If books are being sold (as opposed to given away) sales of the books should not be part of this table, but can be an earlier table for the same line. It is great if the book is offered earlier too so people can be ready to get in line. 2. The speaker will need two (2) helpers – one at their table, one with good printing to go down the line and make a notation of the names wanted on the books on sticky notes for each book. Make sure Sharpie pens are on the desk for signing. 3. The autograph line should be single file and come from one side, (usually the author’s left) not the middle if possible. One helper should go down the line writing names and the requested personalization on small sticky notes. These sticky notes should be a light color and written with a dark pen or marker. Please PRINT the name since this makes it easier to read. This helps keep the line moving since it slows the line if the speaker has to ask about spellings for each name. 4. The person helping the speaker at the table should stand on the same side as the line to take the books and the sticky from the person waiting. -

![Syo1t [Mobile Book] Book Signing 101: an Author's Guide: the Do's, Don'ts Expectations Involved in Professional Book Signings Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9492/syo1t-mobile-book-book-signing-101-an-authors-guide-the-dos-donts-expectations-involved-in-professional-book-signings-online-1099492.webp)

Syo1t [Mobile Book] Book Signing 101: an Author's Guide: the Do's, Don'ts Expectations Involved in Professional Book Signings Online

sYo1T [Mobile book] Book Signing 101: An Author's Guide: The Do's, Don'ts Expectations Involved in Professional Book Signings Online [sYo1T.ebook] Book Signing 101: An Author's Guide: The Do's, Don'ts Expectations Involved in Professional Book Signings Pdf Free Rob Watts ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1706815 in eBooks 2016-12-19 2016-12-19File Name: B01MU2RZX4 | File size: 59.Mb Rob Watts : Book Signing 101: An Author's Guide: The Do's, Don'ts Expectations Involved in Professional Book Signings before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Book Signing 101: An Author's Guide: The Do's, Don'ts Expectations Involved in Professional Book Signings: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Great Resource!By Susan CatalanoLots of good tips for a successful book signing. Already putting some of Rob's ideas into action for my next event!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Very insightful!By Christine StrongiVery insightful. This is a great tool for authors who are venturing into the book signing world. From what to expect to how to present yourself! Glad I found this book!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. New Authors Need This BookBy Stacey B. LongoWatts has participated in many, many book signings over the years, and he's willing to share what he's learned. The author gig isn't as glamorous as you might think. This book tells you straightforwardly how to prepare for a signing, where to find them, and what to expect.