Gillian Mears' Novel Foal's Bread

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Persian Studies and the Celebrations of the 2500Th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire in 1971

British Persian Studies and the Celebrations of the 2500th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire in 1971 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. 2014 Robert Steele School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Declaration .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Copyright Statement ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Objectives and Structure ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Statement on Primary Sources............................................................................................................................... -

2020 Fall Commencement

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Commencement Programs Office of Student Affairs Fall 2020 2020 Fall Commencement Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/commencement- programs Part of the Higher Education Commons This brochure is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Student Affairs at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Twenty-Ninth Annual Fall Commencement 2020 Georgia Southern University SCHEDULE OF CEREMONIES UNDERGRADUATE Sunday, Dec. 13 • 2 p.m. • Savannah Convention Center Wednesday, Dec. 16 • 10 a.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro Wednesday, Dec. 16 • 3 p.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro Thursday, Dec. 17 • 10 a.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro GRADUATE Thursday, Dec. 17 • 3 p.m. • Paulson Stadium in Statesboro COMMENCEMENT NOTES Photography: A professional photographer will take Accessibility Access: If your guest requires a picture of you as you cross the stage. A proof of accommodations for a disability, accessible seating this picture will be emailed to you at your Georgia is available. Guests entering the stadium from the Southern email address and mailed to your home designated handicap parking area should enter address so that you may decide if you wish to through the Media Gate or Gate 13 (Statesboro purchase these photos. Find out more about this Ceremony). Accessible seating for the Savannah service at GradImages.com. ceremonies are available on the right hand side near the back of the Exhibit Hall. -

Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., Et Al. Case

Case 15-10952-KJC Doc 712 Filed 08/05/15 Page 1 of 2014 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: Chapter 11 CORINTHIAN COLLEGES, INC., et al.1 Case No. 15-10952-CSS Debtor. AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE STATE OF CALIFORNIA } } ss.: COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES } SCOTT M. EWING, being duly sworn, deposes and says: 1. I am employed by Rust Consulting/Omni Bankruptcy, located at 5955 DeSoto Avenue, Suite 100, Woodland Hills, CA 91367. I am over the age of eighteen years and am not a party to the above-captioned action. 2. On July 30, 2015, I caused to be served the: a) Notice of (I) Deadline for Casting Votes to Accept or Reject the Debtors’ Plan of Liquidation, (II) The Hearing to Consider Confirmation of the Combined Plan and Disclosure Statement and (III) Certain Related Matters, (the “Confirmation Hearing Notice”), b) Debtors’ Second Amended and Modified Combined Disclosure Statement and Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Combined Disclosure Statement/Plan”), c) Class 1 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 1 Ballot”), d) Class 4 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 4 Ballot”), e) Class 5 Ballot for Accepting or Rejecting Debtors’ Chapter 11 Plan of Liquidation, (the “Class 5 Ballot”), f) Class 4 Letter from Brown Rudnick LLP, (the “Class 4 Letter”), ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are: Corinthian Colleges, Inc. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Company Listing Report (Detail)

Page : 1 of 133 02/16/2018 Company Listing Report (Detail) 10:12 AM Event Types: Support Group; Sanctioned Health; Resident Lifestyle Group; Recreation; Permanent Outdoor; Off Site; Media Exceptions Sorted By: Company Name Geographic Area Phone 1 Company Name Full Address Company Type Phone 2 Phone 3 129 Amigos qF @6PM Coconut Cove Linda Maloney 585 Beaulieu Loop (352) 561-4808 The Villages, FL 32162 Resident Lifestyle Group 200 Ladies Club 2W@9AM Burnsed Gail Hole 1011 Pickering Path (352) 633-0980 The Villages, FL 32163 Resident Lifestyle Group 2012 Discussion Group 2&4W@3P Richard Matwyshen 819 Santa Rita (352) 751-0365 Bridgeport Way The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 26'ers West Ladies Lunch 2TH Pat Miller 1728 Augustine Dr (352) 751-7446 @11:30Am El Santiago The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 26er's Club 2ndM Even Mo. @6P La Barbara Lopiccolo 1320 Augustine (352) 633-3780 Hacienda Drive The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 2nd Honeymoon Club 1stM @7:30PM Mitchell Sheinbaum 1304 Iberia (352) 751-4138 Savannah Court The Villages, FL 32162 Resident Lifestyle Group 4 O'Clock Club 1stW@4PM Chula Vista Richard Petulla 518 Chula Vista (352) 750-5641 Ave The Villages, FL 32159 Resident Lifestyle Group 5 Boroughs Club of NYC 4thF@5:30PM Joseph Herbst 2053 Glenarden (352) 399-5537 Rohan The Villages, FL 32163 Resident Lifestyle Group 5 Streets East 1SA2,5,9,12@6PM Burnsed Patricia Mason 3436 Sassafras Ct (352) 399-6670 The Villages, FL 32163 Resident Lifestyle Group 5-6-7-8Line Dance Prac Impro qW@1PM -

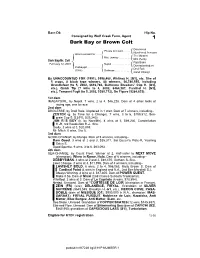

Fasig-Tipton

Barn D6 Hip No. Consigned by Wolf Creek Farm, Agent 1 Dark Bay or Brown Colt Damascus Private Account . { Numbered Account Unaccounted For . The Minstrel { Mrs. Jenney . { Mrs. Penny Dark Bay/Br. Colt . Raja Baba February 12, 2001 Nepal . { Dumtadumtadum {Imabaygirl . Droll Role (1988) { Drolesse . { Good Change By UNACCOUNTED FOR (1991), $998,468, Whitney H. [G1], etc. Sire of 5 crops, 8 black type winners, 88 winners, $6,780,555, including Grundlefoot (to 5, 2002, $616,780, Baltimore Breeders’ Cup H. [G3], etc.), Quick Tip (7 wins to 4, 2002, $464,387, Cardinal H. [G3], etc.), Tempest Fugit (to 5, 2002, $380,712), Go Figure ($284,633). 1st dam IMABAYGIRL, by Nepal. 7 wins, 2 to 4, $46,228. Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, one to race. 2nd dam DROLESSE, by Droll Role. Unplaced in 1 start. Dam of 7 winners, including-- ZESTER (g. by Time for a Change). 7 wins, 3 to 6, $199,512, Sea- gram Cup S. [L] (FE, $39,240). JAN R.’S BOY (c. by Norcliffe). 4 wins at 3, $69,230, Constellation H.-R, 3rd Resolution H.-L. Sire. Drolly. 2 wins at 3, $20,098. Mr. Mitch. 6 wins, 3 to 5. 3rd dam GOOD CHANGE, by Mongo. Dam of 5 winners, including-- Ram Good. 3 wins at 2 and 3, $35,317, 3rd Queen’s Plate-R, Yearling Sales S. Good Sparkle. 9 wins, 3 to 6, $63,093. 4th dam SEA-CHANGE, by Count Fleet. Winner at 2. Half-sister to NEXT MOVE (champion), When in Rome, Hula. -

Progressive Show Jumping 2016

Progressive Show Jumping 2016 POINTS INCLUDE: Palmetto Finals 12/06/15, PSJ Highfields January Show 01/30/16, PSJ Highfields February Show 2/28/16, BRHJA Spring Premier Show 03/20/16, Ashley Hall Show 03/20/16, Harmon Classic Spring Challenge 03/27/16, PSJ Camden Spring Classic II 04/17/16, BRHJA Mother’s Day Celebration 05/08/16, PSJ Mullet Hall Summer Classic06/11/16, PSJ Highfields June Show 06/26/16, PSJ Camden 07/10/16, PSJ Highfields July Show 07/17/16, PSJ Back To School Show 08/07/16 ,PSJ Mullet Hall Fall Classic 09/25/16, PSJ Octoberfest 10/16/16, PSJ Aiken Fall Classic 2 10/23/16, BRHJA Classic Show 10/30/16, Pessoa-Cross Rail Hunter (Horse/Owner/Rider) Champagne Trophy Bellissimo Amelia Turner 552.5 Otterridge Swanson Avery Sheppard 397.5 Surf’s Up Stealing The Show 295.5 Stables/Lillian Cain Grant My Your Heart Sarah Haselden 287.5 Dust Bunny Stealing the Show 211 Stables/Ella Bragg Andy’s Always Right McCall Massey 190.5 Cute As A Button Cailey Duguid 152 Golden Opportunity Grace Truluck 138 Woodlands Pure Platinum Rhett Branham 134 Lakeview Logan’s Way Kate Leonard 126.5 Luck Of The Draw Ann Deputy 117.5 After Midnight Lilly Bridges 104 Wizard Elizabeth Welch/McKenna 103 Szemly Mischief Maker Ella Hudson 90.5 All Smiles Rhett Brabham 65 Bubble Wrap Ella Taruianz 60 Hillcrest My Happiness Virginia Bowers 57 Walk This Way Charles Hairfield/Sophie 53 Baranowski Lonewoods Goldrush Annabelle Anderson 50.5 Nobody’s Fool Lynn Kemp/Katherine Hall 49 Mr White Christmas Ann Deputy/ Addison 45 Beaver Henry Stacia Wolfe/Claire 43 Strickland -

Light Horses : Breeds and Management

' K>\.K>. > . .'.>.-\ j . ; .>.>.-.>>. ' UiV , >V>V >'>>>'; ) ''. , / 4 '''. 5 : , J - . ,>,',> 1 , .\ '.>^ .\ vV'.\ '>»>!> ;;••!>>>: .>. >. v-\':-\>. >*>*>. , > > > > , > > > > > > , >' > > >»» > >V> > >'» > > > > > > . »v>v - . : . 9 '< TUFTS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 3 9090 014 661 80 r Family Libra;-, c veterinary Medium f)HBnf"y Schoo Ve' narv Medicine^ Tu iiv 200 Wesuc . ,-<oao Nerth Graft™ MA 01538 kXsf*i : LIVE STOCK HANDBOOKS. Edited by James Sinclair, Editor of "Live Stock Journal" "Agricultural Gazette" &c. No. II. LIGHT HORSES. BREEDS AND MANAGEMENT BY W. C. A. BLEW, M.A, ; WILLIAM SCARTH DIXON ; Dr. GEORGE FLEMING, C.B., F.R.C.V.S. ; VERO SHAW, B.A. ; ETC. SIZKZTJBI ZEiZDITIOILT, le-IEJ-VISIEID. ILLUSTRATED. XonDon VINTON & COMPANY, Ltd., 8, BREAM'S BUILDINGS, CHANCERY LANE, E.C. 1919. —— l°l LIVE STOCK HANDBOOKS SERIES. THE STOCKBREEDER'S LIBRARY. Demy 8vo, 5s. net each, by post, 5s. 6d., or the set of five vols., if ordered direct from the Publisher, carriage free, 25s. net; Foreign 27s. 6d. This series covers the whole field of our British varieties of Horses, Cattle, Sheep and Pigs, and forms a thoroughly practical guide to the Breeds and Management. Each volume is complete in itself, and can be ordered separately. I. —SHEEP: Breeds and Management. New and revised 8th Edition. 48 Illustrations. By John Wrightson, M.R.A.C., F.C.S., President of the College of Agriculture, Downton. Contents. —Effects of Domestication—Long and Fine-woolled Sheep—British Long-woolled Sheep—Border Leicesters—Cotswolds—Middle-woolled—Mountain or Forest—Apparent Diff- erences in Breeds—Management—Lambing Time— Ordinary and Extraordinary Treatment of Lambs—Single and Twin Lambs—Winter Feeding—Exhibition Sheep—Future of Sheep Farm- ing—A Large Flock—Diseases. -

By Joseph D. Bates Jr. and Pamela Bates Richards (Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Executive Assistant Marianne Kennedy Stackpole Books, 1996)

Thaw HE FEBRUARYTHAW comes to Ver- "From the Old to the New in Salmon mont. The ice melts, the earth loosens. Flies" is our excerpt from Fishing Atlantic TI splash my way to the post office ankle Salmon: The Flies and the Patterns (reviewed deep in puddles and mud, dreaming of being by Bill Hunter in the Winter 1997 issue). waist deep in water. It is so warm I can smell When Joseph D. Bates Jr. died in 1988, he left things. The other day I glimpsed a snow flur- this work in progress. Pamela Bates Richards, ry that turned out to be an insect. (As most his daughter, added significant material to anglers can attest, one often needs to expect the text and spearheaded its publication, to see something in order to see it at all.) Se- working closely with Museum staff during ductive, a tease, the thaw stays long enough her research. The book, released late last year to infect us with the fever, then leaves, laugh- by Stackpole Books, includes more than ing as we exhibit the appropriate withdrawal 160 striking color plates by photographer symptoms. Michael D. Radencich. We are pleased to re- By the time these words are printed and produce eight of these. distributed, I hope the true thaw will be Spring fever finds its expression in fishing upon us here and that those (perhaps few) of and romance in Gordon M. Wickstrom's us who retire our gear for the winter will reminiscence of "A Memoir of Trout and Eros once again be on the water. -

The Angling Library of a Gentleman

Sale 216 - January 18, 2001 The Angling Library of a Gentleman 1. Aflalo, F.G. British Salt-Water Fishes. With a Chapter on the Artificial Culture of Sea Fish by R.B. Marson. xii, 328 + [4] ad pp. Illus. with 12 chromo-lithographed plates. 10x7-1/2, original green cloth lettered in gilt on front cover & spine, gilt vignettes. London: Hutchinson, 1904. Rubbing to joints and extremities; light offset/darkening to title-page, else in very good or better condition, pages unopened. (120/180). 2. Akerman, John Yonge. Spring-Tide; or, the Angler and His Friends. [2], xv, [1], 192 pp. With steel-engraved frontispiece & 6 wood-engraved plates. 6-3/4x4-1/4, original cloth, gilt vignette of 3 fish on front cover, spine lettered in gilt. Second Edition. London: Richard Bentley, 1852. Westwood & Satchell p.3 - A writer in the Gentleman's Magazine, referring to this book, says "Never in our recollection, has the contemplative man's recreation been rendered more attractive, nor the delight of a country life set forth with a truer or more discriminating zest than in these pleasant pages." Circular stains and a few others to both covers, some wear at ends, corner bumps, leaning a bit; else very good. (250/350). WITH ACTUAL SAMPLES OF FLY-MAKING MATERIAL 3. Aldam, W.H. A Quaint Treatise on "Flees, and the Art a Artyfichall Flee Making," by an Old Man Well Known on the Derbyshire Streams as a First-Class Fly-Fisher a Century Ago. Printed from an Old Ms. Never Before Published, the Original Spelling and Language Being Retained, with Editorial Notes and Patterns of Flies, and Samples of the Materials for Making Each Fly. -

Salmon: a Scientific Memoir by Jude Isabella B.A. University of Rhode

Salmon: A Scientific Memoir by Jude Isabella B.A. University of Rhode Island 1985 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Jude Isabella, 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Salmon: A Scientific Memoir by Jude Isabella B.A. University of Rhode Island, 1985 Supervisory Committee Dr. April Nowell (Department of Anthropology) Co-Supervisor David Leach (Department of Writing) Co-Supervisor iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. April Nowell (Department of Anthropology) Co-Supervisor David Leach (Department of Writing) Co-Supervisor The reason for this story was to investigate a narrative that is important to the identity of North America’s Pacific Northwest Coast – a narrative that revolves around wild salmon, a narrative that always seemed too simple to me, a narrative that gives salmon a mythical status, and yet what does the average person know about this fish other than it floods grocery stores in fall and tastes good. How do we know this fish that supposedly defines the natural world of this place? I began my research as a science writer, inspired by John Steinbeck’s The Log from the Sea of Cortez, in which he writes that the best way to achieve reality is by combining narrative with scientific data. So I went looking for a different story from the one most people read about in popular media, a story that’s overwhelmingly about conflict: I searched for a narrative that combines the science of what we know about salmon and a story of the scientists who study the fish, either directly or indirectly. -

I Cowboys and Indians in Africa: the Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Depar

Cowboys and Indians in Africa: The Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Deborah Jenson Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 i v ABSTRACT Cowboys and Indians in Africa: The Far West, French Algeria, and the Comics Western in France by Eliza Bourque Dandridge Department of Romance Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Laurent Dubois, Supervisor ___________________________ Anne-Gaëlle Saliot ___________________________ Ranjana Khanna ___________________________ Deborah Jenson An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Eliza Bourque Dandridge 2017 Abstract This dissertation examines the emergence of Far West adventure tales in France across the second colonial empire (1830-1962) and their reigning popularity in the field of Franco-Belgian bande dessinée (BD), or comics, in the era of decolonization. In contrast to scholars who situate popular genres outside of political thinking, or conversely read the “messages” of popular and especially children’s literatures homogeneously as ideology, I argue that BD adventures, including Westerns, engaged openly and variously with contemporary geopolitical conflicts. Chapter 1 relates the early popularity of wilderness and desert stories in both the United States and France to shared histories and myths of territorial expansion, colonization, and settlement.