The Use of the Principle of Subsidiarity in the Reformation of Australia’S Federal System of Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Negative Implications in the Interpretation of Commonwealth Legislative Powers

THE ROLE OF NEGATIVE IMPLICATIONS IN THE INTERPRETATION OF COMMONWEALTH LEGISLATIVE POWERS MICHAEL STOKES* One of the bases for the view that Commonwealth powers should be interpreted broadly is the idea that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power. The paper argues that far from being wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power it is necessary to do so in that it is impossible to interpret such grants sensibly without drawing negative implications from them. This paper considers Isaacs J’s argument in Huddart Parker that it is wrong to draw negative implications from positive grants of power, as it is the most detailed defence of that position, and the adoption of similar arguments in Work Choices. It then considers the merits of Isaacs J’s argument, rejecting it because it is impossible to interpret positive grants of power without drawing negative implications from them in any context and in the Australian constitutional context in particular. This paper looks at how the scope of such implications is to be determined and how constitutional grants of power ought to be interpreted in the light of negative implications. It concludes that it is possible to determine the scope of the negative implications implicit in the s 51 grants of power and to interpret those powers in the light of the implications while accepting that state powers are residual and that their content cannot be determined until the content of all Commonwealth powers is known. CONTENTS I Introduction .............................................................................................................. 176 II The Origin of the Argument That It Is Wrong to Draw Negative Implications from Positive Grants of Power ....................................................... -

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler

Fact and Law Stephen Gageler* I The essential elements of the decision-making process of a court are well understood and can be simply stated. The court finds the facts. The court ascertains the law. The court applies the law to the facts to decide the case. The distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law corresponds to the distinction in a common law court between the traditional roles of jury and judge. The court - traditionally the jury - finds the facts on the basis of evidence. The court - always the judge - ascertains the law with the benefit of argument. Ascertaining the law is a process of induction from one, or a combination, of two sources: the constitutional or statutory text and the previously decided cases. That distinction between finding the facts and ascertaining the law, together with that description of the process of ascertaining the law, works well enough for most purposes in most cases. * Solicitor-General of Australia. This paper was presented as the Sir N inian Stephen Lecture at the University of Newcastle on 14 August 2009. The Sir Ninian Stephen Lecture was established to mark the arrival of the first group of Bachelor of Laws students at the University of Newcastle in 1993. It is an annual event that is delivered by an eminent lawyer every academic year. 1 STEPHEN GAGELER (2008-9) But it can become blurred where the law to be ascertained is not clear or is not immutable. The principles of interpretation or precedent that govern the process of induction may in some courts and in some cases leave room for choice as to the meaning to be inferred from the constitutional or statutory text or as to the rule to be drawn from the previously decided cases. -

LAWS2150 – Federal Constitutional Law Table of Contents

LAWS2150 – Federal Constitutional Law Table of Contents The Constitution ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Purposes of a Constitution ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Written and unwritten Constitutions .................................................................................................................... 3 Drafting the Constitution ........................................................................................................................................... 3 The High Court and Constitutional Interpretation ................................................................................ 3 Pre-Engineers Approach ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Implied Immunity of Instrumentalities ................................................................................................................................ 3 Reserved State Powers ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 The Engineers Case ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 The Jumbunna Principle -

Ceremonial Sitting of the Tribunal for the Swearing in and Welcome of the Honourable Justice Kerr As President

AUSCRIPT AUSTRALASIA PTY LIMITED ABN 72 110 028 825 Level 22, 179 Turbot Street, Brisbane QLD 4000 PO Box 13038 George St Post Shop, Brisbane QLD 4003 T: 1800 AUSCRIPT (1800 287 274) F: 1300 739 037 E: [email protected] W: www.auscript.com.au TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS O/N H-59979 ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL CEREMONIAL SITTING OF THE TRIBUNAL FOR THE SWEARING IN AND WELCOME OF THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR AS PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KERR, President THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE KEANE, Chief Justice of the Federal Court of Australia THE HONOURABLE JUSTICE BUCHANAN, Presidential Member DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.D. HOTOP DEPUTY PRESIDENT R.P. HANDLEY DEPUTY PRESIDENT D.G. JARVIS THE HONOURABLE R.J. GROOM, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT P.E. HACK SC DEPUTY PRESIDENT J.W. CONSTANCE THE HONOURABLE B.J.M. TAMBERLIN QC, Deputy President DEPUTY PRESIDENT S.E. FROST DEPUTY PRESIDENT R. DEUTSCH PROF R.M. CREYKE, Senior Member MS G. ETTINGER, Senior Member MR P.W. TAYLOR SC, Senior Member MS J.F. TOOHEY, Senior Member MS A.K. BRITTON, Senior Member MR D. LETCHER SC, Senior Member MS J.L REDFERN PSM, Senior Member MS G. LAZANAS, Senior Member DR I.S. ALEXANDER, Member DR T.M. NICOLETTI, Member DR H. HAIKAL-MUKHTAR, Member DR M. COUCH, Member SYDNEY 9.32 AM, WEDNESDAY, 16 MAY 2012 .KERR 16.5.12 P-1 ©Commonwealth of Australia KERR J: Chief Justice, I have the honour to announce that I have received a commission from her Excellency, the Governor General, appointing me as President of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal. -

Papers on Parliament

‘But Once in a History’: Canberra’s David Headon Foundation Stones and Naming Ceremonies, 12 March 1913∗ When King O’Malley, the ‘legendary’ King O’Malley, penned the introduction to a book he had commissioned, in late 1913, he searched for just the right sequence of characteristically lofty, even visionary phrases. After all, as the Minister of Home Affairs in the progressive Labor government of Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, he had responsibility for establishing the new Australian nation’s capital city. Vigorous promotion of the idea, he knew, was essential. So, at the beginning of a book entitled Canberra: Capital City of the Commonwealth of Australia, telling the story of the milestone ‘foundation stones’ and ‘naming’ ceremonies that took place in Canberra, on 12 March 1913, O’Malley declared for posterity that ‘Such an opportunity as this, the Commonwealth selecting a site for its national city in almost virgin country, comes to few nations, and comes but once in a history’.1 This grand foundation narrative of Canberra—with its abundance of aspiration, ambition, high-mindedness, courage and curiosities—is still not well-enough known today. The city did not begin as a compromise between a feuding Sydney and Melbourne. Its roots comprise a far, far, better yarn than that. Unlike many major cities of the world, it was not created because of war, because of a revolution, disease, natural disaster or even to establish a convict settlement. Rather, a nation lucky enough to be looking for a capital city at the beginning of a new century knuckled down to the task with creativity and diligence. -

Review Essay Open Chambers: High Court Associates and Supreme Court Clerks Compared

REVIEW ESSAY OPEN CHAMBERS: HIGH COURT ASSOCIATES AND SUPREME COURT CLERKS COMPARED KATHARINE G YOUNG∗ Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court by Artemus Ward and David L Weiden (New York: New York University Press, 2006) pages i–xiv, 1–358. Price A$65.00 (hardcover). ISBN 0 8147 9404 1. I They have been variously described as ‘junior justices’, ‘para-judges’, ‘pup- peteers’, ‘courtiers’, ‘ghost-writers’, ‘knuckleheads’ and ‘little beasts’. In a recent study of the role of law clerks in the United States Supreme Court, political scientists Artemus Ward and David L Weiden settle on a new metaphor. In Sorcerers’ Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court, the authors borrow from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous poem to describe the transformation of the institution of the law clerk over the course of a century, from benign pupilage to ‘a permanent bureaucracy of influential legal decision-makers’.1 The rise of the institution has in turn transformed the Court itself. Nonetheless, despite the extravagant metaphor, the authors do not set out to provide a new exposé on the internal politics of the Supreme Court or to unveil the clerks (or their justices) as errant magicians.2 Unlike Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong’s The Brethren3 and Edward Lazarus’ Closed Chambers,4 Sorcerers’ Apprentices is not pitched to the public’s right to know (or its desire ∗ BA, LLB (Hons) (Melb), LLM Program (Harv); SJD Candidate and Clark Byse Teaching Fellow, Harvard Law School; Associate to Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG, High Court of Aus- tralia, 2001–02. -

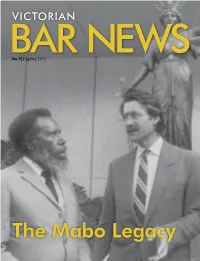

The Mabo Legacy the START of a REWARDING JOURNEY for VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS

No.152 Spring 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN The Mabo Legacy THE START OF A REWARDING JOURNEY FOR VICTORIAN BAR MEMBERS. Behind the wheel of a BMW or MINI, what was once a typical commute can be transformed into a satisfying, rewarding journey. With renowned dynamic handling and refined luxurious interiors, it’s little wonder that both BMW and MINI epitomise the ultimate in driving pleasure. The BMW and MINI Corporate Programmes are not simply about making it easier to own some of the world’s safest, most advanced driving machines; they are about enhancing the entire experience of ownership. With a range of special member benefits, they’re our way of ensuring that our corporate customers are given the best BMW and MINI experience possible. BMW Melbourne, in conjunction with BMW Group Australia, is pleased to offer the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme to all members of The Victorian Bar, when you purchase a new BMW or MINI. Benefits include: BMW CORPORATE PROGRAMME. MINI CORPORATE PROGRAMME. Complimentary scheduled servicing for Complimentary scheduled servicing for 4 years / 60,000km 4 years / 60,000km Reduced dealer delivery charges Reduced dealer delivery charges Complimentary use of a BMW during scheduled Complimentary valet service servicing* Corporate finance rates to approved customers Door-to-door pick-up during scheduled servicing A dedicated Corporate Sales Manager at your Reduced rate on a BMW Driver Training course local MINI Garage Your spouse is also entitled to enjoy all the benefits of the BMW and MINI Corporate Programme when they purchase a new BMW or MINI. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: a Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon*

The Doctrine of Implied Intergovernmental Immunities: A Recrudescence? Thomas Dixon* The essential and distinctive feature of “a truly federal government” is the preservation of the separate existence and corporate life of each of the component States concurrently with that of the national government. Accepting that a number of polities are contemplated as coexisting within a federation does not, however, address the fundamental question of how legislative and executive powers are to be allocated among the constituent constitutional units inter se, nor the extent to which the various polities are immune from interference occasioned by their constitutional counterparts. These “federal” questions are fundamental as they ultimately define the prism through which one views the Constitution. Shifts in the lens have resulted in significant ramifications for intergovernmental relations. This article traces the development of the Melbourne Corporation doctrine in Australia, and undertakes a comparative analysis with the development of the cognate jurisprudence in the United States. Analysis is undertaken of the major Australian industrial relations decisions, such as the Amalgamated Society of Engineers v Adelaide Steamship Co Ltd, Re Australian Education Union; Ex parte Victoria, Queensland Electricity Commission v Commonwealth, and United Firefighters Union of Australia v Country Fire Authority, in this context. But one of the first and most leading principles on which the commonwealth and the laws are consecrated, is left the temporary possessors -

House of Representatives

SESSION 1906. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. SECOND PARLIAMENT. THIRD SESSION-7TH JUNE, 1906, TO 12TH OCTOBER, 1906. Votes Polled Division. for Sitting No. of Electors Name. Member. who Voted. Bamford, Hon. Frederick William ... Herbert, Queensland ... 8,965 16,241 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... 5,775 10,853 Blackwood, Robert Officer, Esq. * Riverina, New South Wales 4,341 8,887 Bonython, Hon. Sir John Langdon ... Barker, South Australia ... Unopposed Braddon, Right Hon. Sir Edward Nichcolas Wilmot, Tasmania S,13 6,144 Coventry, P.C., K.C.M.G. t Brown, Hon. Thomas ... ... Canobolas, New South Wales Unopposed Cameron, Hon. Donald Normant ... Wilmot, Tasmania 2,368 4,704 Carpenter, William Henry, Esquire .. Fremantle, Western Australia 3,439 6,021 Chanter, Hon. John Moore § ... ... Riverina, New South Wales 5,547 10,995 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... ... Eden-Monaro, New South Unopposed Wales Conroy, Hon. Alfred Hugh Beresford ... Werriwa, New South Wales 6,545 9,843 Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 8,657 20,745 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... ... Parramatta, New South 10,097 13,215 Wales Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong ... Corio, Victoria ... 6,951 15,508 Culpin, Millice, Esquire ... Brisbane, Queensland ... 8,019 17,466 Deakin, Hon. Alfred ... ... Ballaarat, Victoria Unopposed Edwards, Hon. George Bertrand .. South Sydney, New South 9,662 17,769 Wales Edwards, Hon. Richard ... Oxley, Queensland ... 8,846 17,290 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson ... Richmond, New South Wales 6,096 8,606 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland ... 10,622 17,698 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia .. -

Who's That with Abrahams

barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008/09 Who’s that with Abrahams KC? Rediscovering Rhetoric Justice Richard O’Connor rediscovered Bullfry in Shanghai | CONTENTS | 2 President’s column 6 Editor’s note 7 Letters to the editor 8 Opinion Access to court information The costs circus 12 Recent developments 24 Features 75 Legal history The Hon Justice Foster The criminal jurisdiction of the Federal The Kyeema air disaster The Hon Justice Macfarlan Court NSW Law Almanacs online The Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina The Hon Justice Ward Saving St James Church 40 Addresses His Honour Judge Michael King SC Justice Richard Edward O’Connor Rediscovering Rhetoric 104 Personalia The current state of the profession His Honour Judge Storkey VC 106 Obituaries Refl ections on the Federal Court 90 Crossword by Rapunzel Matthew Bracks 55 Practice 91 Retirements 107 Book reviews The Keble Advocacy Course 95 Appointments 113 Muse Before the duty judge in Equity Chief Justice French Calderbank offers The Hon Justice Nye Perram Bullfry in Shanghai Appearing in the Commercial List The Hon Justice Jagot 115 Bar sports barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2008-09 Bar News Editorial Committee Cover the New South Wales Bar Andrew Bell SC (editor) Leonard Abrahams KC and Clark Gable. Association. Keith Chapple SC Photo: Courtesy of Anthony Abrahams. Contributions are welcome and Gregory Nell SC should be addressed to the editor, Design and production Arthur Moses SC Andrew Bell SC Jeremy Stoljar SC Weavers Design Group Eleventh Floor Chris O’Donnell www.weavers.com.au Wentworth Chambers Duncan Graham Carol Webster Advertising 180 Phillip Street, Richard Beasley To advertise in Bar News visit Sydney 2000. -

Journal of Supreme Court History

Journal of Supreme Court History THE SUPREME COURT HISTORICAL SOCIETY THURGOOD MARSHALL Associate Justice (1967-1991) Journal of Supreme Court History PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Chairman Donald B. Ayer Louis R. Cohen Charles Cooper Kenneth S. Geller James J. Kilpatrick Melvin I. Urofsky BOARD OF EDITORS Melvin I. Urofsky, Chairman Herman Belz Craig Joyce David O'Brien David J. Bodenhamer Laura Kalman Michael Parrish Kermit Hall Maeva Marcus Philippa Strum MANAGING EDITOR Clare Cushman CONSULTING EDITORS Kathleen Shurtleff Patricia R. Evans James J. Kilpatrick Jennifer M. Lowe David T. Pride Supreme Court Historical Society Board of Trustees Honorary Chairman William H. Rehnquist Honorary Trustees Harry A. Blackmun Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Byron R. White Chairman President DwightD.Opperman Leon Silverman Vice Presidents VincentC. Burke,Jr. Frank C. Jones E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. Secretary Treasurer Virginia Warren Daly Sheldon S. Cohen Trustees George Adams Frank B. Gilbert Stephen W. Nealon HennanBelz Dorothy Tapper Goldman Gordon O. Pehrson Barbara A. Black John D. Gordan III Leon Polsky Hugo L. Black, J r. William T. Gossett Charles B. Renfrew Vera Brown Geoffrey C. Hazard, Jr. William Bradford Reynolds Wade Burger Judith Richards Hope John R. Risher, Jr. Patricia Dwinnell Butler William E. Jackson Harvey Rishikof Andrew M. Coats Rob M. Jones William P. Rogers William T. Coleman,1r. James 1. Kilpatrick Jonathan C. Rose F. Elwood Davis Peter A. Knowles Jerold S. Solovy George Didden IIJ Harvey C. Koch Kenneth Starr Charlton Dietz Jerome B. Libin Cathleen Douglas Stone John T. Dolan Maureen F. Mahoney Agnes N. Williams James Duff Howard T.