Exploring the Self Through Others in 5Rhythms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

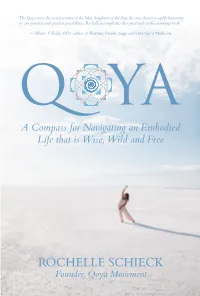

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body. -

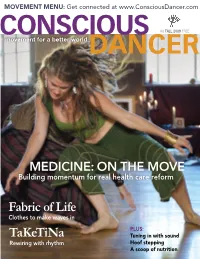

Taketina Tuning in with Sound Rewiring with Rhythm Hoof Stepping a Scoop of Nutrition

MOVEMENT MENU: Get connected at www.ConsciousDancer.com CONSCIOUS #8 FALL 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER MEDICINE: ON THE MOVE Building momentum for real health care reform Fabric of Life Clothes to make waves in PLUS: TaKeTiNa Tuning in with sound Rewiring with rhythm Hoof stepping A scoop of nutrition • PLAYING ATTENTION • DANCE–CameRA–ACtion • BREEZY CLEANSING American Dance Therapy Association’s 44th Annual Conference: The Dance of Discovery: Research and Innovation in Dance/Movement Therapy. Portland, Oregon October 8 - 11, 2009 Hilton Portland & Executive Tower www.adta.org For More Information Contact: [email protected] or 410-997-4040 Earn an advanced degree focused on the healing power of movement Lesley University’s Master of Arts in Expressive Therapies with a specialization in Dance Therapy and Mental Health Counseling trains students in the psychotherapeutic use of dance and movement. t Work with diverse populations in a variety of clinical, medical and educational settings t Gain practical experience through field training and internships t Graduate with the Dance Therapist Registered (DTR) credential t Prepare for the Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC) process in Massachusetts t Enjoy the vibrant community in Cambridge, Massachusetts This program meets the educational guidelines set by the American Dance Therapy Association For more information: www.lesley.edu/info/dancetherapy 888.LESLEY.U | [email protected] Let’s wake up the world.SM Expressive Therapies GR09_EXT_PA007 CONSCIOUS DANCER | FALL 2009 1 Reach -

Dancing Into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism In

Dancing into the Chthulucene: Sensuous Ecological Activism in the 21st Century Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kelly Perl Klein Graduate Program in Dance Studies The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Dr. Harmony Bench, Advisor Dr. Ann Cooper Albright Dr. Hannah Kosstrin Dr. Mytheli Sreenivas Copyrighted by Kelly Perl Klein 2019 2 Abstract This dissertation centers sensuous movement-based performance and practice as particularly powerful modes of activism toward sustainability and multi-species justice in the early decades of the 21st century. Proposing a model of “sensuous ecological activism,” the author elucidates the sensual components of feminist philosopher and biologist Donna Haraway’s (2016) concept of the Chthulucene, articulating how sensuous movement performance and practice interpellate Chthonic subjectivities. The dissertation explores the possibilities and limits of performances of vulnerability, experiences of interconnection, practices of sensitization, and embodied practices of radical inclusion as forms of activism in the context of contemporary neoliberal capitalism and competitive individualism. Two theatrical dance works and two communities of practice from India and the US are considered in relationship to neoliberal shifts in global economic policy that began in the late 1970s. The author analyzes the dance work The Dammed (2013) by the Darpana Academy for Performing Arts in Ahmedabad, -

FINAL Thesis Dance, Empowerment and Spirituality

13 Introduction Imagine entering a space full of people, all engaged with their own movement, emotions and process. Some are dancing fast; others are lying on the floor. Some are stretching their bodies tall in all directions, whereas other movements are barely visible. People may be crying, shouting, or dancing with an expression of joy on their face. There are men and women of all ages, colourfully dressed. If you let your fantasy run wild, you can imagine them as animals swishing their tails while moving stealthily through the jungle, as indigenous people, stamping their feet on the beat. You may see dancing fairies, solid trees and stout warriors. You may see vulnerable, delicate beings of great beauty, or even see seaweeds, moving gently on an invisible current. The raw and the ugly, the wild and the contained, the silence and the storm all may be present in the room. Welcome. You have just arrived in a Movement Medicine space. These spaces form the focus of this research project. Indeed, paraphrasing Performance Studies scholar Fiona Buckland, this research is both a dance floor where people enter and move, and simultaneously a dancer who even now is checking out the floor (F. Buckland, 2002: 14). My baseline motivation for this study is a curiosity about people’s search for meaning and self-understanding in western culture in the early 21st century. The decline of traditional religious frameworks after the Second World War, led to the remarkable rise of many so called alternative spiritualities or New Religious Movements1 (compare Greenwood, 2000: 8). -

University of Movement Giving the Body Credit on Today’S Campuses

MOVEMENT MENU: Fresh Events at MovingArtsNetwork.com CONSCIOUS #6 SPRING 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER Soul Motion Inner-Activating with Vinn Martí Shiva Rea, UCLA graduate, transforms the learning curve. University of Movement GIVIng THE BODY CREDIT ON TODAY’S CAMPUSES PLUS AQua MantRA Lyric of Laban DIVING Into DIGItaL Decoding the DNA of Dance UPLIFTING TRendS 10 Shiva Rea shapes a perfect Natarajasana at the Devi Temple in Chidambaram, India. 16 14 5 MENTOR Lyric of Laban Rudolf Laban created a system for mapping movement that is still in use today. Ahead of FEATURES his time in the early 20th century, he created a poetic language of science and motion. 7 WARMUPS 10 Minister of Soul • Recession-proof Trendspotting Departments Diving into the mystery of the present moment • Let Your Moves Be Your Music with Vinn Martí. Editor Mark Metz shares a day of • Debbie Rosas: The Body’s Business movement with the founder of Soul Motion. • Disco Revival Saves Lives 20 VITALITY Drink Up! 14 Laura Cirolia follows her intuition to discover Dance, Dance, Education natural truths about the water we drink and why The convergence of mind and body is good news proper hydration is so important. IN D in the world of academia. 23 SOUNDS Diving into Digital ON PU R 14 In higher education, the buzzword is embodiment. Eric Monkhouse demystifies the digital options facing DJs today and provides helpful tips for EWIJK / New curricula embrace the body at interdisciplinary D O L institutions around the country. performing live with a laptop. -

Women's Experience of 5 Rhythms Dance and the Effects on Their Emotional Wellbeing

Women's experience of 5 Rhythms dance and the effects on their emotional wellbeing Sarah Cook, Karen Ledger and Nadine Scott 2003 Written by Sarah Cook, Karen Ledger and Nadine Scott Published in 2003 By: U.K. Advocacy Network 14-18 West Bar Green Sheffield S1 2DA Tel 0114 2728171 Fax 0114 2727786 Email [email protected] Dancing for Living Women’s experience of 5 Rhythms dance and the effects on their emotional wellbeing Copyright © 2003 Sarah Cook, Karen Ledger and Nadine Scott ISBN 0 9537303 3 6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in any retrieval system of any nature, without the written permission of the copyright holder, to whom the application should be made in writing. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the contents of this publication. However the U.K. Advocacy Network cannot accept liability for any errors which may occur. Further Copies are available from UKAN at the address above. Printed in England by: Alphagraphics Weston House, West Bar Green Sheffield, S1 2DA Tel: 0114 2750076 Fax: 0114 2750350 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Research Methods 4 The Participants 9 Our Experience of Dancing 5 Rhythms 11 Transformation Through Dance 14 Effects on Day to Day Living 16 What Helps People to Take Part 18 Personal Accounts 20 Discussion 22 References and Information 26 Acknowledgements 26 Appendix 1, The Dance Workshop Flier 27 Appendix 2, Teaching 5 Rhythms 28 3 are so loaded with different meanings, or Introduction when examined, are unclear. -

Self-Cultivation & Spiritual Practice

HCOL 186F Sophomore Seminar (13485), Spring 2019 Self-Cultivation & Spiritual Practice: Comparative Perspectives Course director: Prof. Adrian Ivakhiv, [email protected] Office: Room 211, Bittersweet House, 153 South Prospect Street (at Main St.) Consultation hours: Tue. 3:00-4:00 pm, Thur. 10:00 am-12:00 pm Appointments: Book through Cathy Trivieres (x. 64055, [email protected]) or Outlook Class meetings: Tuesday & Thursday 1:15-2:30 pm, University Heights North 16 Overview This course introduces students to the comparative study of religious, spiritual, and psycho-physical practices—exercises by which individuals and groups deepen, develop, challenge, and transform their perceptions and capacities for action in harmony with religious, moral-ethical, or philosophical ideals. The course covers a range that spans from ancient Greek and Roman philosophers (such as Stoics, Epicurians, and Neoplatonists), yogis and monks of South and East Asia, Christian and Muslim ascetics and Renaissance mages, to practitioners of modern forms of westernized yoga, martial arts, ritual magic, and environmental and spiritual activism. Readings of ancient texts and contemporary philosophical and sociological writings are complemented by practical exercises, writing and presentation assignments, and a practice project. COURSE DESCRIPTION Philosophers in the ancient world were less interested in knowledge for its own sake than in the "art of living." From ancient Greece and Rome to China and India, the core of philosophical practice often consisted of spiritual exercises (askesis, ἄσκησις, Gk.) aimed at self-cultivation (xiushen, 修真, Ch.). This interest has been revived in today's growing fascination with spiritual practices undertaken both within and well outside the context of traditional religion. -

Cd25-Ilovepdf-Compressed 2

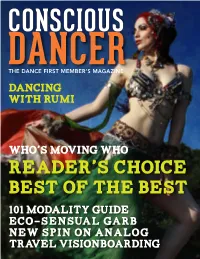

CONSCIOUS DANCERTHE DANCE FIRST MEMBER’S MAGAZINE DANCING WITH RUMI WHo’s mOVING WHO R EADER’s chOICE BEST OF THE BEST 101 MODALITY GUIDE ECO-SENSUAL GARB NEW SPIN ON ANALOG TrAVEL VISIONBOARDING PHOTO: SCOT BELDING CONSCIOUS DANCER MAGAZINE CONTENTS WINNERS: Best-of 1,000,001 PLACES Conscious Dance TO DANCE A big heart full of every one of A comprehensive listing of the well-loved leaders, products, websites, organizations, and and programs that make this regional dances from around the movement tick. world. DANCING WITH RUMI SPINNING INTO THE A pair of serendipitous analog artifacts that illustrate the love NEW YEAR and dancing wisdom of the Sufi Your guide to getting set up with master in sensuous calligraphy. analog sound in your home or studio. Turntable tips and resources 101 MOVEMENT for record finding. MODALITIES YOUTH ON THE MOVE Discover the world’s most Dynamic organizations and leaders comprehensive collection of cultivating a growing conscious mind-body-spirit practices, listed body intelligence movement in alphabetically from 5Rhythms to youth. Zumba. DANCE @ HOME UPSHIFT GUIDE Portfolio pages introducing you to Log onto movement with these the members of the Dance First virtual and online programs you Association. Meet the modalities at can access in-house or on the go. the heart of the movement. FEELING THE VIBES EcO SENSUAL Analog modalities that move your body and spirit with the magic of GARB GUIDE voice, drums, and living sound. Meet the makers of the world’s finest eco-sensual clothing and SOMATIC SYLLABUS conscious adornment. A collection of forward-thinking and innovative educational 30 SOMATIC HOTSPOTS institutions that are blazing new Our pick of the very best places trails in the world of academia. -

Guide for Starting an Ecstatic Dance

Guide for Starting an Ecstatic Dance This guide is written by Tyler Blank and Peter Weinstein. Tyler co-founded Ecstatic Dance Oakland, San Francisco, and Ecstatic Dance Retreat Hawaii. Peter co-founded Ecstatic Dance Corvallis, and Dance Immersion, and Tyler and Peter together founded Ecstatic Dance Fairfax in Marin, CA. All of these dances are now thriving community gatherings. In addition to being Producers and Managers of Ecstatic Dances, Peter Tyler are also Ecstatic Dance DJs: Peter plays as Baron Von Spirit, and Tyler as Avani. They have each musically facilitated (DJ’d) hundreds of Ecstatic Dances, throughout California, the US, and around the World. This guide is based on our experiences, what has worked and what needs improvement—with wisdom gathered from both our own experiences, as well as experiences of many other dance leaders around the world. Many of the suggestions in this guide are presented as a series of questions for inquiry. It is simply a Guide. The steps are numbered, but your order may be different. Only you how to best serve your community. 1. Develop your Vision Make sure you understand why you are starting this and what you’re your intentions are • Create a vision statement or mission statement o For Example: “We Desire a Safe and Sacred Space for Freeform Movement, on a Weekly Basis, in an Wonderful and Expansive Environment.” Get to know Dance History and Modern Electronic Music • Research the history of dance in modern and ancient times for your own knowledge and understanding of the movement you are co-Creating • Read the Origin Story of Ecstatic Dance found on www.Edance.org/Origins • What are the health benefits of dance? Why people dance, why you dance. -

5Rhythms by Gabrielle Roth

5Rhythms of Gabrielle Roth in her own words Written By: Gabrielle Roth Movement Each of us is a moving center, a space of divine mystery. And though we spend most of our time on the surface in the daily details of ordinary existence, most us hunger to connect to this space within, to break through to ecstatic states of consciousness, to be swept away. As a young dancer, I made the transition from the world of steps and structures to the world of transformation and trance by exposure to live drumming. The beats, the patterns, the rhythms kept calling me deeper and deeper into trance. These dances took me from the edge of myself to the moving center. And from there, I began to discover a more essential me. Being young, wild, and free, it didnʼt dawn on me that in order to go into these deep ecstatic places, I would have to be willing to transform absolutely everything that got in my way. That included every form of inertia known to us: the physical inertia of tight and stressed muscles; the emotional baggage of depressed, repressed feelings; the mental baggage of dogmas, attitudes, and philosophies. In other words, Iʼd have to let it all go—everything. Rhythm is a refuge, movement is medicine, and energy is a language. In a parallel universe, I was teaching movement to tens of thousands of people and, in them, I began to witness my own body/spirit split. Between the head and feet of any given person is a billion miles of unexplored wilderness. -

5Rhythms Yin Yoga Sound

PHOTOCREDITS HERE PHOTOCREDITS 5RHYTHMS with Evelyn Switajewski YIN YOGA with Peta Walker SOUND with Demir Aliu August 4th 2 – 6pm Aireys Inlet As part of 'Love Winter in Aireys' produced by Evelyn Switajewski, a one off workshop, come join us for some Winter nurturing with Dance, Yoga and Sound. EVELYN For over 20 years Evelyn has facilitated groups within the community. Her career began at the Victorian College of the Arts where she trained in Dance and subsequently continued to become a qualified Dance Movement Therapist (IDTIA). Evelyn has also studied Yoga at the Byron Yoga School and has completed Reiki levels 1 and 2. Evelyn has been a 5Rhythms Sweat Spaceholder since 2015 and a Certified 5Rhythms Teacher since 2018 and has been offering 5Rhythms to the Surf Coast and Melbourne communities since 2016. Bringing people together to grow and learn through a sensory body experience is one of Evelyn’s passions. PETA Peta has been living and practising yoga for the past 18 years on the Surf Coast. She has completed a Yin Yoga Training and a 500 hour Yoga Teacher Training with Byron Yoga Centre which incorporates asana, pranayama, philosophy and meditation with Yoga Nidra. Yoga, for Peta is about seeking a consistently peaceful flow of mind in life. Teaching yoga and developing her own personal practice has enriched and enhanced this flow. Yin Yoga is a deeply nourishing practice that works from a place of calm and surrender. Postures are floor based and held for longer periods of time with the support of props. We focus on finding a deep sense of stillness and connection to breath. -

Soul Loss and Retrieval: Restoring Wholeness Through Dance

Chapter 6 Soul loss and retrieval: Restoring wholeness through dance Eline Kieft Prelude My journey with dance started at a local ballet school in a small village in the Netherlands, at age 7. I happened to be a lucky child, whose natural exploration of movement was never thwarted, but instead encouraged. My pre-professional training at the National Ballet Academy (Academy of Theatre and Dance) in Amsterdam (age 10–13) and Codarts’ Havo voor Muziek en Dans in Rotterdam (age 14–16) gave me a wide movement vocabulary, leading to subsequent professional training at age 16. Through the strict school regimes and pedagogy, the exhilarating sense of expression and connection that I used to feel when dancing slowly disappeared. Technique became a prison, disconnected from feeling, intuition, meaning and the world around me. This loss of connection was one of the main reasons I decided not to pursue a career as a professional dancer. Over the years, I came to realize that dance can embrace so much more than performance; I returned again to appreciating the precision of mastering a technique, but as a way to enjoy freedom within structure. I decided to study cultural and medical anthropology, where I became fascinated with healing and other ways of knowing. In 2005, I was introduced to basic shamanic techniques during a workshop called Soul in Nature, facilitated by Dr. Christian de Quincey, Dr. Stephan Harding and Jonathan Horwitz at Schumacher College in Devon. This three-week intensive course fundamentally shifted my compartmentalized outlook on life to one of a profound, felt, embodied knowing of interconnection.