Boultham Park, Lincoln

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

535 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

535 bus time schedule & line map 535 Lincoln View In Website Mode The 535 bus line Lincoln has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Lincoln: 5:55 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 535 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 535 bus arriving. Direction: Lincoln 535 bus Time Schedule 71 stops Lincoln Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 5:55 AM Central Bus Station, Lincoln Norman Street, Lincoln Tuesday 5:55 AM Siemens, Lincoln Wednesday 5:55 AM Pelham Street, Lincoln Thursday 5:55 AM East West Link Road, Lincoln Friday 5:55 AM A57, Lincoln Saturday Not Operational Thomas Cooper Church, Lincoln 370 High Street, Lincoln St Peter at Gowt's Church, Lincoln 105 High Street, Lincoln 535 bus Info Direction: Lincoln Sewell's Walk, Lincoln Stops: 71 406 High Street, Lincoln Trip Duration: 50 min Line Summary: Central Bus Station, Lincoln, Robey Street, Lincoln Siemens, Lincoln, East West Link Road, Lincoln, 445-446 High Street, Lincoln Thomas Cooper Church, Lincoln, St Peter at Gowt's Church, Lincoln, Sewell's Walk, Lincoln, Robey Street, Tealby Street, Lincoln Lincoln, Tealby Street, Lincoln, Hamilton Road, St 14-16 High Street, Lincoln Catherine's, Otter's Cottages, Bracebridge, Manby Street, Bracebridge, Ellison Street, Bracebridge, Hamilton Road, St Catherine's Grosvenor Nursing Home, Bracebridge, All Saints Hamilton Road, Lincoln Church, Brant Road, Parker Avenue, Brant Road, Broughton Gardens, Brant Road, Glendon Close, Otter's Cottages, Bracebridge Brant Road, Glenarm -

Annex E Revised Site Allocations Policies Lp49

CENTRAL LINCOLNSHIRE LOCAL PLAN EXAMINATION ANNEX E REVISED SITE ALLOCATIONS POLICIES LP49 – LP53 1 Policy LP49: Residential Allocations – Lincoln The following sites, as identified on the Policies Map, are allocated primarily for residential use: Lincoln Urban Area Ref. Address Site Area Status* Indicative (ha) Dwellings/ Remaining Capacity* CL1068 Land to North of Station Road, Waddington (former 13.29 UC 117 Brick Pits site) CL1099 Land at Thorpe Lane, South Hykeham 1.47 NS 38 CL1113 Mill Lane/Newark Road, North Hykeham 33.97 UC 228 320 CL1328 LF7 Land west of Nettleham Road, Lincoln Fringe 3.78 NS 95 CL1687 LF2/3 Land off Wolsey Way 16.41 UC 328 305 CL1882 Land off Millbeck Drive, Lincoln 1.34 46 CL2098 Former Lincoln Castings Site A, Plot 1, Station 10.44 UC 310 244 Road, North Hykeham CL252 Land rear of No 44 and 46 Station Road 0.31 NS 33 CL4379 Land at Junction of Brant Road and Station Road 1.34 46 Waddington CL4394 Land North of Hainton Road, Lincoln 1.14 39 CL452 Former Parade Ground, Nene Road, Lincoln, LN1 2.68 UC 54 3PL CL4615 North West of Lincoln Road Romangate, Lincoln 3.29 99 60 CL4430 2.17 CL4652 Land at and North of Usher Junior School 3.57 81 CL4704 Land off Western Avenue, Lincoln 0.88 30 CL4735 Mill House and Viking House, Lincoln 0.48 101 CL515 Romangate Development, Land at Nettleham 7.10 NS 80 Road, Lincoln CL516 RMSC Playing Fields, Newark Road Lincoln LN6 8.27 NS 8RT CL525 Former CEGB Power Station, Spa Road, Lincoln, 5.71 300 LN2 5TB CL526 Former Main Hospital Complex, St Anne's Road, 4.20 126 Lincoln CL529 -

Unlocking New Opportunies

A 37 ACRE COMMERCIAL PARK ON THE A17 WITH 485,000 SQ FT OF FLEXIBLE BUSINESS UNITS UNLOCKING NEW OPPORTUNIES IN NORTH KESTEVEN SLEAFORD MOOR ENTERPRISE PARK IS A NEW STRATEGIC SITE CONNECTIVITY The site is adjacent to the A17, a strategic east It’s in walking distance of local amenities in EMPLOYMENT SITE IN SLEAFORD, THE HEART OF LINCOLNSHIRE. west road link across Lincolnshire connecting the Sleaford and access to green space including A1 with east coast ports. The road’s infrastructure the bordering woodlands. close to the site is currently undergoing The park will offer high quality units in an attractive improvements ahead of jobs and housing growth. The site will also benefit from a substantial landscaping scheme as part of the Council’s landscaped setting to serve the needs of growing businesses The site is an extension to the already aims to ensure a green environment and established industrial area in the north east resilient tree population in NK. and unlock further economic and employment growth. of Sleaford, creating potential for local supply chains, innovation and collaboration. A17 A17 WHY WORK IN NORTH KESTEVEN? LOW CRIME RATE SKILLED WORKFORCE LOW COST BASE RATE HUBS IN SLEAFORD AND NORTH HYKEHAM SPACE AVAILABLE Infrastructure work is Bespoke units can be provided on a design and programmed to complete build basis, subject to terms and conditions. in 2021 followed by phased Consideration will be given to freehold sale of SEE MORE OF THE individual plots or constructed units, including development of units, made turnkey solutions. SITE BY SCANNING available for leasehold and All units will be built with both sustainability and The site is well located with strong, frontage visibility THE QR CODE HERE ranging in size and use adaptability in mind, minimising running costs from the A17, giving easy access to the A46 and A1 (B1, B2 and B8 use classes). -

Lost Features of Boultham Park

Lost Features of Boultham Park The lake History and Importance Boultham Park is listed in English Heritage’s Register of Historic Parks and Gardens as Grade 2 and therefore ‘of special interest which warrants every effort being made to preserve it’. The Park is a Critical Natural Asset and has been designated by Lincolnshire Wildlife Trust as a ‘site of nature conservation importance’. It is one of the largest areas of woodland within Lincoln and one of nine predominantly woodland sites within the city and in a local context the site supports some rare and endangered species. About The Boultham Estate underwent a period of development under Colonel Richard Ellison, who was a Justice of the Peace and Deputy Lieutenant of Lincolnshire, there is a record dating from Picture1 1851 of discussions surrounding incorporating a lake into the parkland close to the hall and this came to fruition in 1857 when the large ornamental lake was excavated. The lake took its feed water from Pike Drain (Pike Drain is fed from the lakes at Whisby, you can see this drain alongside Newark Road opposite the Ruston Sports Ground, it then runs through Boultham Moor skirting The Witham Academy crossing Rookery Lane at the end of Westwick Drive) the overspill water from the lake was diverted by a catchwater into the River Witham The original lake was constructed in a ‘serpentine’ shape (looks like a goose neck in picture 1) and was excavated by hand, the majority of the soil removed was deposited round the site to produce garden area and raise the ground level at the east side of the lake up to the River Witham https://www.flickr.com/ photos/boulthampark/ albums Check out the Boultham Park Archive for more great images of the Lake The Lake Picture2 Picture3 At the time of construction the park covered an area of over 1,000 acres and the lake covered 4 acres. -

Lincolnshire GP Practice List

Lincolnshire GP Practice List NHS Lincolnshire West CCG Abbey Medical Practice Arboretum Surgery Bassingham Surgery Birchwood Medical Practice Boultham Medical Practice Caskgate Surgery Brant Road Surgery Brayford Medical Practice Burton Road Surgery Branston & Heighington Practice Hibaldstow Medical Practice Cleveland Surgery Cliff House Medical Practice Cliff Villages Surgery Crossroads Medical Practice Glebe Park Surgery Glebe Practice Hawthorn Surgery Church Walk Surgery Ingham Practice Lindum Medical Practice Metheringham Surgery Minster Medical Practice Nettleham Medical Practice Newark Road Surgery Portland Medical Practice Pottergate Surgery Richmond Medical Centre Springcliffe Surgery The Heath Surgery Trent Valley Surgery University Health Centre Washingborough Surgery Welton Family Health Centre Willingham by Stow Surgery Witham Practice Woodland Medical Practice Service provided by NHS South West Lincolnshire CCG Belvoir Vale Surgery Billinghay Medical Practice Caythorpe and Ancaster Medical Practice Colsterworth Medical Practice Glenside Country Practice Harrowby Lane Surgery Long Bennington Medical Centre Market Cross Surgery Millview Medical Centre New Springwells Medical Practice Ruskington Medical Practice Sleaford Medical Group St John’s Medical Centre St Peter’s Hill Surgery Stackyard Surgery Swingbridge Surgery Vine House Surgery Welby Practice Woolsthorpe Surgery NHS South Lincolnshire CCG Church Street Surgery Beechfield Medical Centre Gosberton Medical Centre -

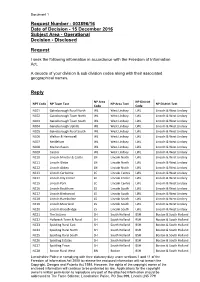

Request Number - 003896/16 Date of Decision - 15 December 2016 Subject Area - Operational Decision - Disclosed

Document 1 Request Number - 003896/16 Date of Decision - 15 December 2016 Subject Area - Operational Decision - Disclosed Request I seek the following information in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act. A decode of your division & sub division codes along with their associated geographical names. Reply NP Area NP District NPT Code NP Team Text NP Area Text NP District Text Code Code NC01 Gainsborough Rural North WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC02 Gainsborough Town North WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC03 Gainsborough Town South WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC04 Gainsborough Uphills WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC05 Gainsborough Rural South WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC06 Welton & Hemswell WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC07 Nettleham WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC08 Market Rasen WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC09 Caistor WL West Lindsey LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC10 Lincoln Minster & Castle LN Lincoln North LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC11 Lincoln Glebe LN Lincoln North LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC12 Lincoln Abbey LN Lincoln North LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC13 Lincoln Carholme LC Lincoln Centre LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC14 Lincoln City Centre LC Lincoln Centre LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC15 Lincoln Park LC Lincoln Centre LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC16 Lincoln Boultham LS Lincoln South LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC17 Lincoln Birchwood LS Lincoln South LWL Lincoln & West Lindsey NC18 Lincoln Hartsholme LS Lincoln -

Proposed Site Allocations

Proposed site allocations The tables below set out at a glance the proposed site allocations for the Local Plan. They have been broken down into the following: Proposed new allocations – sites without planning permission Proposed new allocations – sites with planning permission Existing allocations – carried forwards Information in relation to planning permissions is as of April 2020. Some sites may have gained planning permission since then and these figures will be updated once the most up to date monitoring information is taken into account. The indicative no. of dwellings figure may also be subject to change following consultation. Proposed new allocations – sites without planning permission Indicative Site Reference Address no. of Area Dwellings COL/MIN/005 Land at Cathedral Quarry, Riseholme Road, Lincoln 2.74 82 NK/BAS/007 Land south of Torgate Road and east of Carlton Road 2.68 24 NK/BAS/010 Land at Whites Lane, Bassingham 1.77 35 NK/BIL/006A Land to the rear of 79 & 79a Walcott Road, Billinghay 1.53 33 NK/BRAN/007 Land to the west of Station Road and north of Nettleton Close 1.64 35 NK/EAG/005 Land at Back Lane, Eagle 0.94 16 NK/GHAL/002 Land at Hall Farm, Great Hale 1.10 19 NK/HEC/004 Land off Sleaford Road, Heckington 2.05 38 NK/HEC/007 Land east of Kyme Road, Heckington 1.06 33 NK/KIRK/003 Land off Ewerby Road, Kirkby la Thorpe 0.91 15 NK/LEAD/001 Station Yard, Leadenham, Cliff Road, Leadenham, LN5 OPL 1.31 22 NK/LEAS/001 Land off Meadow Lane, Leasingham 2.01 25 NK/MART/001 Land at 114 High Street, Martin, Lincoln, LN4 3QT -

Land Belonging to Upper Witham Internal Drainage Board CA-7-1-66

Parish: Broxholme, Burton by Lincoln, Grantham, Hardwick, Lincoln, North Hykeham, Saxilby with Ingleby, Scampton, Skellingthorpe, South Hykeham, Sturton by Stow, Waddington Title: Land belonging to the Upper Witham Internal Drainage Board Reference number: CA/7/1/66 DEPOSIT OF MAP AND STATEMENT UNDER SECTION 31(6) OF THE HIGHWAYS ACT 1980 Details about the Deposit Landowner’s name: Upper Witham Internal Drainage Board Landowner’s address: 39 St Catherines, Lincoln LN5 8LU Date of deposit of the 01 April 1993 map and statement: Date on which the map 31 March 1999 and statement expires: Geographic Location Grid Reference: SK 858 768, SK 879 738, SK 903 787, SK 913 746, SK 914 377, SK 916 755, SK 920 793, SK 924 724, SK 938 659, SK 942 720, SK 944 647, SK 944 651, SK 947 673, SK 949 733, SK 954 719, SK 955 651, SK 955 663, SK 958 675, SK 969 694, SK 969 702, SK 971 693 Address(es) and 39 St Catherines Lincoln LN5 8LP postcode of any buildings on the land: Postcodes covering LN1 2, LN5 8, LN5 9, LN6 0, LN6 5, LN6 7, LN6 8, LN6 9, NG23 7, the area land: NG31 8 Principal city or town Grantham, Lincoln nearest to land: Parish: Broxholme, Burton by Lincoln, Grantham, Hardwick, Lincoln, North Hykeham, North Hykeham, Saxilby with Ingleby, Scampton, Skellingthorpe, South Hykeham, Sturton by Stow, Waddington Electoral Division: Bassingham Rural, Bracebridge Heath and Waddington, Gainsborough Rural South, Grantham North, Hykeham Forum, Lincoln Boultham, Lincoln Bracebridge, Lincoln West, Nettleham and Saxilby, Skellingthorpe and Hykeham South District: -

The Impact of Community Grassroots Campaigns on Public Library Closures

THE IMPACT OF COMMUNITY GRASSROOTS CAMPAIGNS ON PUBLIC LIBRARY CLOSURES John Mowbray This dissertation was submitted in part fulfilment of requirements for the degree of MSc Information and Library Studies DEPT. OF COMPUTER AND INFORMATION SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF STRATHCLYDE September 2014 DECLARATION This dissertation is submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MSc of the University of Strathclyde. I declare that this dissertation embodies the results of my own work and that it has been composed by myself. Following normal academic conventions, I have made due acknowledgement to the work of others. I declare that I have sought, and received, ethics approval via the Departmental Ethics Committee as appropriate to my research. I give permission to the University of Strathclyde, Department of Computer and Information Sciences, to provide copies of the dissertation, at cost, to those who may in the future request a copy of the dissertation for private study or research. I give permission to the University of Strathclyde, Department of Computer and Information Sciences, to place a copy of the dissertation in a publicly available archive. Yes [ ] No [ ] I declare that the word count for this dissertation (excluding title page, declaration, abstract, acknowledgements, table of contents, list of illustrations, references and appendices is 22,111. I confirm that I wish this to be assessed as a Type 1 2 3 4 5 Dissertation Signature: Date: II Abstract Community grassroots campaigns against proposed public library closures have been locked into conflicts with local authorities across the UK in recent years. No previous research has been specifically aimed at the plight of these local library activists, and so the researcher was keen to explore who they are, what they do, and the impact they have on the overall library closure process. -

Division Arrangements for Grantham Barrowby

Hougham Honington Foston Ancaster Marston Barkston Long Bennington Syston Grantham North Sleaford Rural Allington Hough Belton & Manthorpe Great Gonerby Sedgebrook Londonthorpe & Harrowby Without Welby Grantham Barrowby Barrowby Grantham East Grantham West W Folkingham Rural o o l s t h o r Ropsley & Humby p e Grantham South B y B e l v o i r Old Somerby Harlaxton Denton Little Ponton & Stroxton Colsterworth Rural Boothby Pagnell Great Ponton County Division Parish 0 0.5 1 2 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Grantham Barrowby © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Syston Grantham North Belton & Manthorpe Great Gonerby Hough Heydour Welby Barrowby Londonthorpe & Harrowby Without Braceby & Sapperton Grantham East Folkingham Rural Grantham West Grantham South Grantham Barrowby Ropsley & Humby Old Somerby Harlaxton Colsterworth Rural Little Ponton & Stroxton Boothby Pagnell County Division Parish 0 0.35 0.7 1.4 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 Grantham East © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Division Arrangements for 100049926 2016 Claypole Stubton Leasingham Caythorpe North Rauceby Hough-on-the-Hill Normanton Westborough & Dry Doddington Sleaford Ruskington Sleaford Hougham Carlton Scroop South Rauceby Hough L o n g Ancaster B e n n i n Honington g t o Foston n Wilsford Silk Willoughby Marston Barkston Grantham North Syston Culverthorpe & Kelby Aswarby & Swarby Allington Sleaford Rural Belton & Manthorpe -

Final Evaluation and Legacy Planning

Quarterly report (Oct. 2020 - March 2021). Project Ref: HG– 15-03574 Update Report No.7 October 2020 - March 2021 Welcome to our 7th edition of the Love Lincs Plants (LLP) project update report. Learn more about what has been achieved so far, upcoming events and opportunities to get involved in this exciting National Lottery Heritage Fund project (2017-2021). Covid-19 update: All public facing project events, including plant collection continue to be suspended until further notice. For our up to date policy click here Great Lives Lectures on Zoom In response to Covid-19 the project team have adapted to the challenging circumstances, and continue to engage with existing and new participants using digital platforms. In December, we hosted our second Great Lives lecture with former government nature conservation advisor Dr Chris Gibson exploring the adaptations of coastal plants to environmental stresses . In March, University of Lincoln lecturer Ian Jackson engaged with seventy two Zoom attendees on the vital role of plants in herbal medicine providing further evidence on how plants are essential for sustaining human life. Find out more about our final four Great Lives lectures on page 2. “ Thanks again for such a great talk - really looking forward to future ones! Been really useful - I am focusing on Saltfleetby-Theddlethorpe dunes NNR for my assessment module at University so it's been great to have this talk right now! Finished Identiplant now & my lovely mum is getting me BSBI membership for Christmas so looking forward to more botanising next year!” (Amy Primavera - 18 to 35 botanist - Dr Gibson lecture feedback) Final evaluation and legacy planning We are now in the final phase of the project after gaining an extension from our funders, The National Lottery Heritage Fund until 30th June 2021. -

PROCTOR TRAIL Learn About Lincoln's Cycling Network and Safe

TIGER MOTH TRAIL HANDLEY Distance: 55 mile circular route PAGE TRAIL Start: Cycle Hub at Lincoln Railway Station Distance: 45 mile circular route The Tiger Moth trail will take you out of Lincoln along the Start: St Marks Shopping Centre “Water Rail Way” - an off-road cycle route - to Woodhall Spa, home of the famous “Dambusters” 617 Squadron, where you This cycle challenge will can visit their Officers’ Mess at the Petwood Hotel. take you out of the city and After going on to Coningsby - home to the up Cross O’Cliff Hill to “The Battle of Britain Memorial Flight - you will Heath”, home to operational return via the RAF Metheringham Heritage airfields at Waddington and Centre and the Cemetery at Scopwick where Digby and the world famous John Magee, the young Canadian author of RAF College, Cranwell. You will “High Flight” and other airmen from a number also pass disused airfields and of nations are buried. visit war graves. HAMPDEN Your route back to Lincoln is over “The Heath”, The Handley Page Type O TRAIL home to many airfields during World War II. was an early biplane bomber You will pass through Bracebridge Heath where used by Britain during the First you can make a detour to visit the International Distance: 38 mile circular route World War. The Type O was the Scampton Saxilby Bomber Command Centre. Allow plenty of time Nettleham Start: Visitor Information Centre YOU Fiskerton2 1 ARE Lincoln Doddington 3 Bardney Horncastle largest aircraft that had been Whisby 13 12 4 for visits on this fascinating long distance route.