Recognising Absurdity Through Compositional Practice Comparing an Avant-Garde Style with Being Avant Garde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger Smalley: a Case-Study of Post -50S Western Music

Research Report: Roger Smalley: A Case-Study of Post -50s Western Music Christopher Mark When I gave a seminar on Roger Smalley's Concerto for Piano and Orchestra at the University of Melbourne in April 1992, a number of people asked me 'Why Smalley?' I'm still not sure quite how to take this. The general reaction to the work, and to my presentation, was positive (at least, that was the impression I gained), and I don't think the question was of the 'why are you spending your time on this drivel' variety. I think it arose because very few people in the audience of staff and graduate students had heard the work-which is remarkable given its high prominence as winner of the Paris Rostrum, its relatively heathy number of broadcasts and its wide availability on an Australian Music Centre CD (Vox Australis, VAST 003-21988)- and were puzzled as to how I had heard of him. My answer, which I suspect they may have found naive, was simply that I had known of Smalley when he was still in the LJK, and had heard a few of the early Australian pieces (such as the Symphony and the Konzertstiidc for solo violin and orchestra) when they were broadcast on BBC radio. I had liked the music and wanted to get to know it better. I still hold that this is the most important impulse for the academic study of music. It drives all my research. And with Smalley I can be very precise about what drew me to his scores: the expressive range of both the Concerto and the other work on the CD I have mentioned, the Symphony, and the sense that every note has been fully considered. -

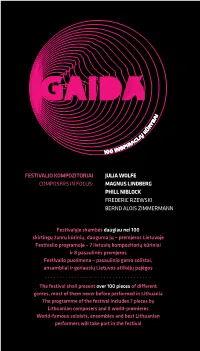

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Teaching Electronic Music – Journeys Through a Changing Landscape

Revista Vórtex | Vortex Music Journal | ISSN 2317–9937 | http://vortex.unespar.edu.br/ D.O.I.: https://doi.org/10.33871/23179937.2020.8.1.12 Teaching electronic music – journeys through a changing landscape Simon Emmerson De Montfort University | United Kingdom Abstract: In this essay, electronic music composer Simon Emmerson examines the development of electronic music in the UK through his own experience as composer and teacher. Based on his lifetime experiences, Emmerson talks about the changing landscape of teaching electronic music composition: ‘learning by doing’ as a fundamental approach for a composer to find their own expressive voice; the importance of past technologies, such as analogue equipment and synthesizers; the current tendencies of what he calls the ‘age of the home studio’; the awareness of sonic perception, as opposed to the danger of visual distraction; questions of terminology in electronic music and the shift to the digital domain in studios; among other things. [note by editor]. Keywords: electronic music in UK, contemporary music, teaching composition today. Received on: 29/02/2020. Approved on: 05/03/2020. Available online on: 09/03/2020. Editor: Felipe de Almeida Ribeiro. EMMERSON, Simon. Teaching electronic music – journeys throuGh a chanGinG landscape. Revista Vórtex, Curitiba, v.8, n.1, p. 1-8, 2020. arly learning. The remark of Arnold Schoenberg (in the 1911 Preface to his Theory of Harmony) – “This book I have learned from my pupils” – is true for me, too. Teaching is E learning – without my students I would not keep up nearly so well with important changes in approaches to music making, and it would be more difficult to develop new ideas and skills. -

Cimf20201520program20lr.Pdf

CONCERT CALENDAR See page 1 Beethoven I 1 pm Friday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 6 2 Beethoven II 3.30 pm Friday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 6 3 Bach’s Universe 8 pm Friday May 1 Fitters’ Workshop 16 4 Beethoven III 10 am Saturday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 7 5 Beethoven IV 2 pm Saturday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 7 6 Beethoven V 5.30 pm Saturday May 2 Fitters’ Workshop 8 7 Bach on Sunday 11 am Sunday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 18 8 Beethoven VI 2 pm Sunday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 9 9 Beethoven VII 5 pm Sunday May 3 Fitters’ Workshop 9 Sounds on Site I: 10 Midday Monday May 4 Turkish Embassy 20 Lamentations for a Soldier 11 Silver-Garburg Piano Duo 6 pm Monday May 4 Fitters’ Workshop 24 Sounds on Site II: 12 Midday Tuesday May 5 Mt Stromlo 26 Space Exploration 13 Russian Masters 6 pm Tuesday May 5 Fitters’ Workshop 28 Sounds on Site III: 14 Midday Wednesday May 6 Shine Dome 30 String Theory 15 Order of the Virtues 6 pm Wednesday May 6 Fitters’ Workshop 32 Sounds on Site IV: Australian National 16 Midday Thursday May 7 34 Forest Music Botanic Gardens 17 Brahms at Twilight 6 pm Thursday May 7 Fitters’ Workshop 36 Sounds on Site V: NLA – Reconciliation 18 Midday Friday May 8 38 From the Letter to the Law Place – High Court Barbara Blackman’s Festival National Gallery: 19 3.30 pm Friday May 8 40 Blessing: Being and Time Fairfax Theatre 20 Movers and Shakers 3 pm Saturday May 9 Fitters’ Workshop 44 21 Double Quartet 8 pm Saturday May 9 Fitters’ Workshop 46 Sebastian the Fox and Canberra Girls’ Grammar 22 11 am Sunday May 10 48 Other Animals Senior School Hall National Gallery: 23 A World of Glass 1 pm Sunday May 10 50 Gandel Hall 24 Festival Closure 7 pm Sunday May 10 Fitters’ Workshop 52 1 Chief Minister’s message Festival President’s Message Welcome to the 21st There is nothing quite like the Canberra International Music sense of anticipation, before Festival: 10 days, 24 concerts the first note is played, for the and some of the finest music delights and surprises that will Canberrans will hear this unfold over the 10 days of the Festival. -

A Perspective of New Simplicity in Contemporary Composition: Song of Songs As a Case Study Isabel Maria Pereira Barata Da Rocha

MESTRADO COMPOSIÇÃO E TEORIA MUSICAL A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha 06/2017 A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha MESTRADO M COMPOSIÇÃO E TEORIA MUSICAL A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha Dissertação apresentada à Escola Superior de Música e Artes do Espetáculo como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Composição e Teoria Musical Professor Orientador Professor Doutor Eugénio Amorim Professora Coorientadora Professora Doutora Daniela Coimbra 06/2017 A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha Dedico este trabalho a todos os homens e todas as mulheres de boa vontade. A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha A perspective of New Simplicity in contemporary composition: Song of Songs as a case study. Isabel Maria Pereira Barata da Rocha Agradecimentos À minha filha Luz, que me dá a felicidade de ser sua mãe, pelo incentivo. Aos meus pais Ana e Luís, pelo apoio incondicional. A Ermelinda de Jesus, pela ajuda sempre disponível. À Fátima, à Joana e à Mariana, pela amizade profunda. Ao José Bernardo e aos avós Teresa e António José, pelo auxílio. Ao Pedro Fesch, pela compreensão e pela aposta na formação dos professores em quem confia. -

Ferienkurse Für Internationale Neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946

Ferienkurse für internationale neue Musik, 25.8.-29.9. 1946 Seminare der Fachgruppen: Dirigieren Carl Mathieu Lange Komposition Wolfgang Fortner (Hauptkurs) Hermann Heiß (Zusatzkurs) Kammermusik Fritz Straub (Hauptkurs) Kurt Redel (Zusatzkurs) Klavier Georg Kuhlmann (auch Zusatzkurs Kammermusik) Gesang Elisabeth Delseit Henny Wolff (Zusatzkurs) Violine Günter Kehr Opernregie Bruno Heyn Walter Jockisch Musikkritik Fred Hamel Gemeinsame Veranstaltungen und Vorträge: Den zweiten Teil dieser Übersicht bilden die Veranstaltungen der „Internationalen zeitgenössischen Musiktage“ (22.9.-29.9.), die zum Abschluß der Ferienkurse von der Stadt Darmstadt in Verbindung mit dem Landestheater Darmstadt, der „Neuen Darmstädter Sezession“ und dem Süddeutschen Rundfunk, Radio Frankfurt, durchgeführt wurden. Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit So., 25.8. Erste Schloßhof-Serenade Kst., 11.00 Ansprache: Bürgermeister Julius Reiber Conrad Beck Serenade für Flöte, Klarinette und Streichorchester des Landes- Streichorchester (1935) theaters Darmstadt, Ltg.: Carl Wolfgang Fortner Konzert für Streichorchester Mathieu Lange (1933) Solisten: Kurt Redel (Fl.), Michael Mayer (Klar.) Kst., 16.00 Erstes Schloß-Konzert mit neuer Kammermusik Ansprachen: Kultusminister F. Schramm, Oberbürger- meister Ludwig Metzger Lehrkräfte der Ferienkurse: Paul Hindemith Sonate für Klavier vierhändig Heinz Schröter, Georg Kuhl- (1938) mann (Kl.) Datum Veranstaltungstitel und Programm Interpreten Ort u. Zeit Hermann Heiß Sonate für Flöte und Klavier Kurt Redel (Fl.), Hermann Heiß (1944-45) (Kl.) Heinz Schröter Altdeutsches Liederspiel , II. Teil, Elisabeth Delseit (Sopr.), Heinz op. 4 Nr. 4-6 (1936-37) Schröter (Kl.) Wolfgang Fortner Sonatina für Klavier (1934) Georg Kuhlmann (Kl.) Igor Strawinsky Duo concertant für Violine und Günter Kehr (Vl.), Heinz Schrö- Klavier (1931-32) ter (Kl.) Mo., 26.8. Komponisten-Selbstporträts I: Helmut Degen Kst., 16.00 Kst., 19.00 Einführung zum Klavierabend Georg Kuhlmann Di., 27.8. -

Festival Artists

Festival Artists Cellist OLE AKAHOSHI (Norfolk competitions. Berman has authored two books published by the ’92) performs in North and South Yale University Press: Prokofiev’s Piano Sonatas: A Guide for the Listener America, Asia, and Europe in recitals, and the Performer (2008) and Notes from the Pianist’s Bench (2000; chamber concerts and as a soloist electronically enhanced edition 2017). These books were translated with orchestras such as the Orchestra into several languages. He is also the editor of the critical edition of of St. Luke’s, Symphonisches Orchester Prokofiev’s piano sonatas (Shanghai Music Publishing House, 2011). Berlin and Czech Radio Orchestra. | 27th Season at Norfolk | borisberman.com His performances have been featured on CNN, NPR, BBC, major German ROBERT BLOCKER is radio stations, Korean Broadcasting internationally regarded as a pianist, Station, and WQXR. He has made for his leadership as an advocate for numerous recordings for labels such the arts, and for his extraordinary as Naxos. Akahoshi has collaborated with the Tokyo, Michelangelo, contributions to music education. A and Keller string quartets, Syoko Aki, Sarah Chang, Elmar Oliveira, native of Charleston, South Carolina, Gil Shaham, Lawrence Dutton, Edgar Meyer, Leon Fleisher, he debuted at historic Dock Street Garrick Ohlsson, and André-Michel Schub among many others. Theater (now home to the Spoleto He has performed and taught at festivals in Banff, Norfolk, Aspen, Chamber Music Series). He studied and Korea, and has given master classes most recently at Central under the tutelage of the eminent Conservatory Beijing, Sichuan Conservatory, and Korean National American pianist, Richard Cass, University of Arts. -

Download Booklet

SAM HAYDEN FREE DOWNLOAD from our online store Sam Hayden Die Abkehr 11’07 Ensemble Musikfabrik • Stefan Asbury conductor Helen Bledsoe fl ute/piccolo/alto fl ute · Peter Veale oboe/cor anglais Richard Haynes contrabass clarinet · Rike Huy trumpet/piccolo trumpet Bruce Collings trombone · Benjamin Kobler piano · Dirk Rothbrust percussion Hannah Weirich violin · Axel Porath viola · Dirk Wietheger cello Håkon Thelin double bass Enter code: HAYDEN247 nmcrec.co.uk/recording/dieabkehr Die Abkehr (Turning Away) is the most recent drive or melodic elegance of a particular part one composition presented here. As Hayden explains, moment, to the dialogic interplay between different ‘[t]he more poetic meanings of the title hint at a instruments the next and the more complex and critical commentary on the increasingly nostalgic diffuse surface of the totality at another time. What and inward-looking culture of the UK’. Abkehr also remains tantalisingly out of reach is an appreciation means ‘renunciation’, and to what extent that title of the whole and its constituent parts at the same time. is expressed more specifi cally in the piece, over and Again like earlier works, Die Abkehr is highly above being embodied by a musical language that episodic: there are three movements, each seems out of step with what the composer sees as consisting of a number of short individual sections the dominant trends in the UK and that is largely each exploring a particularly type of material. If shared with the rest of his oeuvre is hard to say. As anything, however, Hayden appears to have grown the composer also states, the composition ‘is the bolder in his use of the general pause: time and latest of a cycle of pieces that combine ideas related again, the music recedes into silence, before to “spectral” traditions with algorithmic approaches starting afresh. -

John Clark Brian Charette Finn Von Eyben Gil Evans

NOVEMBER 2016—ISSUE 175 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM JOHN BRIAN FINN GIL CLARK CHARETTE VON EYBEN EVANS Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East NOVEMBER 2016—ISSUE 175 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : John Clark 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : Brian Charette 7 by ken dryden General Inquiries: [email protected] On The Cover : Maria Schneider 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : Finn Von Eyben by clifford allen Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : Gil Evans 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : Setola di Maiale by ken waxman US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, CD Reviews Stuart Broomer, Thomas Conrad, 14 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Philip Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, Miscellany 33 Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Event Calendar 34 Ken Micallef, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman Contributing Writers Robert Bush, Laurel Gross, George Kanzler, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman It is fascinating that two disparate American events both take place in November with Election Contributing Photographers Day and Thanksgiving. -

54 by Paul Griffiths As Is Well Known, Hugo Vernier

Formulae and Spectra The Quiet Pioneering of Jonathan Harvey, 1967-73 by Paul Griffiths As is well known, Hugo Vernier, in his poetry collection Le Voyage d’hiver (1864), anticipated celebrated works by Stéphane Mallarmé, Arthur Rim- baud, Paul Verlaine, and many more.1 Readers may therefore need to be assured that, in making similar claims for Jonathan Harvey, this essay is dealing with a composer who had a real existence. Happily, the Jonathan Harvey Collection held by the Paul Sacher Stiftung contains abundant evidence of that existence, including, besides scores and sketches, a hardback notebook (henceforth HN) the composer seems to have kept by him throughout his adult life, in order to catalogue his works, at one end of the book, and, at the other, inverted, to jot down notes on his reading and creative ideas. Dates appear infrequently among those notes, though of course the succession is some indication of chronology. We can thus be sure it was before July 5, 1967, that Harvey proposed venturing into a domain that would be of lasting importance to him, that of electronic music. This first potential step involved the foundation instru- ment of Stockhausen’s Momente – one of two Stockhausen works he had witnessed at Darmstadt the previous summer in the films by Luc Ferrari, the other being Mikrophonie I. His project now was his Cantata II, and the note in question asks “Electronic organ?” The answer was to be in the negative, but the impression left by those Stockhausen experiences remained, as revealed in the note of the later date just mentioned, which has to be quoted in full: 5.7.67 Noh Play setting. -

Darmstadt As Other: British and American Responses to Musical Modernism. Twentieth-Century Music, 1 (2)

Heile, B. (2004) Darmstadt as other: British and American responses to musical modernism. Twentieth-Century Music, 1 (2). pp. 161-178. ISSN 1478-5722 Copyright © 2004 Cambridge University Press A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge The content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/52652/ Deposited on: 03 April 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk twentieth century music http://journals.cambridge.org/TCM Additional services for twentieth century music: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Darmstadt as Other: British and American Responses to Musical Modernism BJÖRN HEILE twentieth century music / Volume 1 / Issue 02 / September 2004, pp 161 178 DOI: 10.1017/S1478572205000162, Published online: 22 April 2005 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1478572205000162 How to cite this article: BJÖRN HEILE (2004). Darmstadt as Other: British and American Responses to Musical Modernism. twentieth century music, 1, pp 161178 doi:10.1017/S1478572205000162 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TCM, IP address: 130.209.6.42 on 03 Apr 2013 twentieth-century music 1/2, 161–178 © 2004 Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S1478572205000162 Printed in the United Kingdom Darmstadt as Other: British and American Responses to Musical Modernism BJO}RN HEILE Abstract There is currently a backlash against modernism in English-language music studies. -

A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century

A SCENE WITHOUT A NAME: INDIE CLASSICAL AND AMERICAN NEW MUSIC IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY William Robin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Mark Katz Andrea Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Benjamin Piekut © 2016 William Robin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT WILLIAM ROBIN: A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century (Under the direction of Mark Katz) This dissertation represents the first study of indie classical, a significant subset of new music in the twenty-first century United States. The definition of “indie classical” has been a point of controversy among musicians: I thus examine the phrase in its multiplicity, providing a framework to understand its many meanings and practices. Indie classical offers a lens through which to study the social: the web of relations through which new music is structured, comprised in a heterogeneous array of actors, from composers and performers to journalists and publicists to blog posts and music venues. This study reveals the mechanisms through which a musical movement establishes itself in American cultural life; demonstrates how intermediaries such as performers, administrators, critics, and publicists fundamentally shape artistic discourses; and offers a model for analyzing institutional identity and understanding the essential role of institutions in new music. Three chapters each consider indie classical through a different set of practices: as a young generation of musicians that constructed itself in shared institutional backgrounds and performative acts of grouping; as an identity for New Amsterdam Records that powerfully shaped the record label’s music and its dissemination; and as a collaboration between the ensemble yMusic and Duke University that sheds light on the twenty-first century status of the new-music ensemble and the composition PhD program.