Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne Brian Best ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 122 November 2012

No. 122 November 2012 THE RED HACKLE RAF A4 JULY 2012_Layout 1 01/08/2012 10:06 Page 1 their future starts here Boarding Boys & Girls aged 9 to 18 Scholarship Dates: Sixth Form Saturday 17th November 2012 Junior (P5-S1) Saturday 26th January 2013 Senior (Year 9/S2) Monday 25th – Wednesday 27th February 2013 Forces Discount and Bursaries Available For more information or to register please contact Felicity Legge T: 01738 812546 E: [email protected] www.strathallan.co.uk Forgandenny Perthshire PH2 9EG Strathallan is a Scottish Charity dedicated to education. Charity number SC008903 No. 122 42nd 73rd November 2012 THE RED HACKLE The Chronicle of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment), its successor The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland, The Affiliated Regiments and The Black Watch Association The Old Colours of the 1st Battalion The Black Watch and 1st Battalion 51st Highland Volunteers were Laid Up in Perth on 23 June 2012. This was the final military act in the life of both Regiments. NOVEMBER 2012 THE RED HACKLE 1 Contents Editorial ..................................................................................................... 3 Regimental and Battalion News .............................................................. 4 Perth and Kinross The Black Watch Heritage Appeal, The Regimental Museum and Friends of the Black Watch ...................................................................... 8 is proud to be Correspondence ..................................................................................... -

Terminology & Rank Structure

Somerset Cadet Bn (The Rifles) ACF Jellalabad HouseS 14 Mount Street Taunton Somerset TA1 3QE t: 01823 284486 armycadets.com/somersetacf/ facebook.com/SomersetArmyCadetForce Terminology & Rank Structure The Army Cadets and the armed forces can be a minefield of abbreviations that can confound even the most experienced person, never mind a new cadet or adult instructor. To address that this document has been prepared that will hopefully go some way towards explanation. If you train with the regular or reserve armed forces you will come across many of the more obscure acronyms. Naturally this document is in a state of continuous update as new and mysterious acronyms are created. ACRONYMS/TERMINOLOGY AAC Army Air Corp accn Accommodation ACFA Army Cadet Force Association Adjt Adjutant Admin Administration, or as in Personal Admin - “sort your kit out” AFD Armed Forces Day AFV Armoured Fighting Vehicle, tracked fighting vehicle, see MBT AI Adult Instructor (NCO) (initials Ay Eye) Ammo Ammunition AOSB Army Officer Selection Board AR Army Reserve (formerly Territorial Army) Armd Armoured AROSC Army Reserve Operational Shooting Competition (formerly TASSAM) Arty Artillery, as in Arty Sp - artillery support ATC Air Training Corps Att Attached, as in Attached Personnel - regular soldiers helping Basha Personal Shelter BATSIM Battlefield Simulation, eg Pyro (see below) Bde Brigade BFA Blank Firing Adaptor/Attachment Blag To acquire something BM Bugle Major/Band Master 20170304U - armycadets.com/somersetacf Bn Battalion Bootneck A Royal Marines Commando -

Revised Tri Ser Pen Code 11 12 for Printing

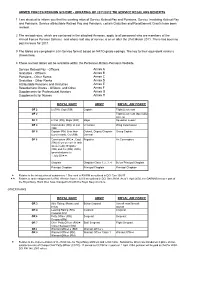

ARMED FORCES PENSION SCHEME - UPRATING OF 2011/2012 TRI SERVICE REGULARS BENEFITS 1 I am directed to inform you that the existing rates of Service Retired Pay and Pensions, Service Invaliding Retired Pay and Pensions, Service attributable Retired Pay and Pensions, certain Gratuities and Resettlement Grants have been revised. 2 The revised rates, which are contained in the attached Annexes, apply to all personnel who are members of the Armed Forces Pension Scheme and whose last day of service is on or after the 31st March 2011. There has been no pay increase for 2011. 3 The tables are compiled in a tri-Service format based on NATO grade codings. The key to their equivalent ranks is shown here. 4 These revised tables will be available within the Personnel-Miltary-Pensions Website. Service Retired Pay - Officers Annex A Gratuities - Officers Annex B Pensions - Other Ranks Annex C Gratuities - Other Ranks Annex D Attributable Pensions and Gratuities Annex E Resettlement Grants - Officers, and Other Annex F Supplements for Professional Aviators Annex G Supplements for Nurses Annex H ROYAL NAVY ARMY ROYAL AIR FORCE OF 2 Lt (RN), Capt (RM) Captain Flight Lieutenant OF 2 Flight Lieutenant (Specialist Aircrew) OF 3 Lt Cdr (RN), Major (RM) Major Squadron Leader OF 4 Commander (RN), Lt Col Lt Colonel Wing Commander (RM), OF 5 Captain (RN) (less than Colonel, Deputy Chaplain Group Captain 6 yrs in rank), Col (RM) General OF 6 Commodore (RN)«, Capt Brigadier Air Commodore (RN) (6 yrs or more in rank (preserved)); Brigadier (RM) and Col (RM) (OF6) (promoted prior to 1 July 00)«« Chaplain Chaplain Class 1, 2, 3, 4 Below Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain Principal Chaplain « Relates to the introduction of substantive 1 Star rank in RN/RM as outlined in DCI Gen 136/97 «« Relates to rank realignment for RM, effective from 1 Jul 00 as outlined in DCI Gen 39/99. -

The Annals of the Four Masters De Búrca Rare Books Download

De Búrca Rare Books A selection of fine, rare and important books and manuscripts Catalogue 142 Summer 2020 DE BÚRCA RARE BOOKS Cloonagashel, 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. 01 288 2159 01 288 6960 CATALOGUE 142 Summer 2020 PLEASE NOTE 1. Please order by item number: Four Masters is the code word for this catalogue which means: “Please forward from Catalogue 142: item/s ...”. 2. Payment strictly on receipt of books. 3. You may return any item found unsatisfactory, within seven days. 4. All items are in good condition, octavo, and cloth bound, unless otherwise stated. 5. Prices are net and in Euro. Other currencies are accepted. 6. Postage, insurance and packaging are extra. 7. All enquiries/orders will be answered. 8. We are open to visitors, preferably by appointment. 9. Our hours of business are: Mon. to Fri. 9 a.m.-5.30 p.m., Sat. 10 a.m.- 1 p.m. 10. As we are Specialists in Fine Books, Manuscripts and Maps relating to Ireland, we are always interested in acquiring same, and pay the best prices. 11. We accept: Visa and Mastercard. There is an administration charge of 2.5% on all credit cards. 12. All books etc. remain our property until paid for. 13. Text and images copyright © De Burca Rare Books. 14. All correspondence to 27 Priory Drive, Blackrock, County Dublin. Telephone (01) 288 2159. International + 353 1 288 2159 (01) 288 6960. International + 353 1 288 6960 Fax (01) 283 4080. International + 353 1 283 4080 e-mail [email protected] web site www.deburcararebooks.com COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Our cover illustration is taken from item 70, Owen Connellan’s translation of The Annals of the Four Masters. -

Statistical Release UK Armed Forces Annual Personnel Report

UK Armed Forces Annual Personnel Report 1 April 2013 The UK Armed Forces Annual Personnel Report contains figures on strength, intake and outflow of UK Regular Forces. It complements the UK Armed Forces Quarterly and Monthly Personnel Reports by providing greater detail about the sex, ethnicity and rank of the Statistical release Armed Forces. It uses data from the Ministry of Defence Joint Personnel Administration System (JPA). Published: 23 May 2013 (Reissued 26 November 2013) The tables present information about the composition of the UK’s Armed Forces in the most recent financial year. Contents Page Contents page 2 Armed Forces Personnel Key Points and Trends Commentary 3 UK Regular Forces: Strength At 1 April 2013: Table 1 UK Regular Forces Rank 6 There were 170,710 UK Regular Forces personnel, Structure of which 29,060 were officers and 141,650 were Table 1a UK Regular Forces Rank other ranks. Structure by Sex and 7 Ethnicity The percentage of women in the UK Regular Forces Table 2 UK Regular Forces Strength was 9.7% in April 2013. 8 by Service and Age Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) personnel Table 3 UK Regular Officers 9 comprised 7.1% of the UK Regular Forces, Strength by Age and Sex continuing a long term gradual increase in the Table 4 UK Regular Other Ranks 9 Strength by Age and sex proportion of BME personnel. Graph 6 Strength by UK Regular 10 56% of Army personnel were aged under 30, Forces by Age and Rank compared with 48% of the Naval Service and 40% UK Regular Forces: Intake and of the RAF. -

B32 Supplement to the London Gazette, 12Th June 1993

B32 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 12TH JUNE 1993 lacking anaesthetic and even the most basic of surgical 24504786 Corporal Nicholas Keith PETTIT, instruments, the strain upon Warrant Officer McNair was immense. Horrific though it may seem, Corps of Royal Engineers. circumstances forced him to undertake some Corporal Pettit was deployed as a section amputations with domestic scissors. When not commander for six months on Operation GRAPPLE assisting in surgical operations Warrant Officer from November 1992 to April 1993. He spent most of McNair spent his time tending injured and dying this period on detached duty with a company group of people. Several people, including some young children, the 1st Battalion The Cheshire Regiment who were died in his arms. working in support of humanitarian operations. As During what was a most traumatic ordeal Warrant such he was often the senior Royal Engineer in his Officer McNair acted with courage and immense location and was frequently called upon to give advice humanity. He showed great professionalism and and carry out tasks beyond what would normally be selfless courage at considerable danger to himself. expected of him. For one period Corporal Pettit supported a company group who lived in a disused factory which 24254006 Colour Sergeant John Charles ORAM, was without mains supplied water or electricity. The Cheshire Regiment. Corporal Pettit commanded a maintenance team which provided the company with the essential During Operation GRAPPLE Colour Sergeant facilities needed to live there in reasonable comfort. He Oram was independently deployed to Sarajevo with displayed a great deal of initiative and made an four armoured personnel carriers. -

Blue Plaques in Bromley

Blue Plaques in Bromley Blue Plaques in Bromley..................................................................................1 Alexander Muirhead (1848-1920) ....................................................................2 Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (1807-1889)...................................................3 Brass Crosby (1725-1793)...............................................................................4 Charles Keeping (1924-1988)..........................................................................5 Enid Blyton (1897-1968) ..................................................................................6 Ewan MacColl (1915-1989) .............................................................................7 Frank Bourne (1855-1945)...............................................................................8 Harold Bride (1890-1956) ................................................................................9 Heddle Nash (1895-1961)..............................................................................10 Little Tich (Harry Relph) (1867-1928).............................................................11 Lord Ted Willis (1918-1992)...........................................................................12 Prince Pyotr (Peter) Alekseyevich Kropotkin (1842-1921) .............................13 Richmal Crompton (1890-1969).....................................................................14 Sir Geraint Evans (1922-1992) ......................................................................15 Sir -

3178 Supplement to the London Gazette, May 2,1879

3178 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, MAY 2,1879, Regiment. Names. Acts of Courage for which recommended. 2nd Battalion 24th Private Henry Hook These two men together, one -man working .whilst Regiment the other fought and held the enemy at bay with his bayonet, broke through three more partitions, and were thus enabled to bring eight patients through a small window into the inner line of defence. 2nd Battalion 24th Private .William Jones and In another ward, facing the hill, Private William Regiment Private Robert Jones Jones and Private Robert Jones defended the post to the last, until six out of the seven patients it contained had been removed. The seventh, Sergeant Maxfield, 2nd Battalion 24th Regiment, was delirious from fever. Although they had previously dressed him, they were un- able to induce him to move. When Private Robert Jones returned to endeavour to carry him away, he found him being stabbed by the Zulus as he lay on his bed. 2nd Battalion 24th Corporal William Allen and It was chiefly due to the courageous conduct of Regiment Private Frederick Hitch these men that communication with the hospital was kept up at all. Holding together at all costs a most dangerous post, raked in re- verse by the enemy's fire from the hill, they were both severely wounded, but their de- termined conduct enabled the patients to be withdrawn from the hospital, and when incapaci- tated by their wounds from fighting, they con- tinued, as soon as their wounds had been dressed, to serve out ammunition to their comrades during the night. -

Rorkes Drift Free Download

RORKES DRIFT FREE DOWNLOAD Adrian Greaves | 464 pages | 01 Feb 2004 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780304366415 | English | London, United Kingdom Rorke’s Drift, South Africa: The Complete Guide The fighting now concentrated on the wall of biscuit barrels linking the mission house with the mealie wall. The corner room that John Williams had pulled the two patients into was occupied by Private Hook and another nine patients. Carnage and Culture. Depleted by injuries and fielding only ten men for much of the second half, the English outclassed and outfought the Australians in what quickly became known as the " Rorke's Drift Test ". More Zulus are estimated to have died in this way than in Rorkes Drift, but the executions were hushed up to preserve Rorke's Drift's image as a bloody but clean fight between two forces which saluted the other's courage. However, the force turned out to be the vanguard of Lord Chelmsford 's relief column. Documents have been uncovered which show that Rorke's Drift was the scene of an atrocity - a war crime, in today's language - which Britain covered up. The surviving patients were rescued after soldiers hacked holes in the walls separating the rooms, and dragged them through and into the barricaded yard. The British garrison set to fortifying the mission station. These regiments had not been involved in the battle and looked for a way to join in the success. The Zulus captured some 1, Martini Henry breech loading rifles Rorkes Drift a large amount of ammunition. And the defenders forced back any who did manage to climb over. -

Full Day Isandlwana & Rorke's Drift Battlefields Tour

FULL DAY ISANDLWANA & RORKE’S DRIFT BATTLEFIELDS TOUR (SD9) • R2 340 PER PERSON KwaZulu Natal is rich in Anglo-Zulu military history and there are many sites around the country that bear witness to brutal battles that raged between the British Army and the Zulu warriors. This full day tour takes you on a fascinating journey through the lush countryside to the battlefields of Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift. A knowledge guide will regale tales of heroism on both sides and bring to life the struggles and tribulations of soldiers who fought for country and honour. Battle of Isandlwana Tour days: Departs Saturday (except 25-26 The Battle of Isandlwana was fought on 22 January 1879 and was December and 1 January) the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Duration: approx 12.5 hours Empire and the Zulu Kingdom. A Zulu force of some 20 000 warriors Pick up: 06h45 attached a portion of the British main column which consisted of Drop off: 19h30 about 1 800 British, colonial and native troops and about 400 civilians. Pick up and drop off available at no extra charge The Zulu force outnumbered the British column but they were from various Durban beachfront hotels equipped mainly with traditional assegai iron spears and cow-hide Pick up and drop off from hotels in other suburbs in shields and just a few muskets and old rifles. The British soldiers Durban available on request at an extra charge were armed with Martini-Henry breech-loading rifles and two 7-pound Tour duration and collection times may vary artillery pieces as well as a rocket battery. -

Zulu War Victoria Cross Holders Brian Best ______

Zulu War Victoria Cross Holders Brian Best __________________________________________________________________________________________ The Victoria Cross - the ultimate accolade, Britain’s highest honour for bravery in battle. The award that has an awesome mystique. There is something brooding about the dark bronze of the medal with its dull crimson ribbon that sets it apart from the glittering silver and colourful ribbons of other awards. The medals were awarded for acts performed in terrifying and bloody circumstances; the tunnel vision of spontaneous bravery in saving a helpless comrade; the calculated act because there was no alternative or that the risk is worth taking. There may have been a handful that deliberately sought the highest decoration but, to the great majority, a medal was the last thing to be considered in the mind-numbing heat of battle. After the hero was feted by a grateful nation, the Victoria Cross could bring it’s own problems for its recipient. The qualities that made a man a hero in battle could elude him in times of peace. Of the 1,354 men who have won the VC, 19 committed suicide, far higher than the national average, although almost all were Victorian. About the same number have died in suspect circumstances (see Cecil D’Arcy). Many fell on hard times and died in abject poverty, having sold their hard earned Cross for a pittance. Most officer recipients, in contrast, prospered, as did many other ranks who were held in high esteem by their neighbours. To some men, the Cross changed their lives for the better while others could not come to terms with it’s constant reminder of nightmarish events. -

Cra-Newsletter-Vol-2-Iss-24

ENT ASSOCI EGIM ATIO E R N N IR EW SH SL HE ET THE C TER VOLUME 2 ISSUE 24 DECEMBER 2015 EDITORIAL CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN As the days get shorter and colder and the year draws News, firstly, from the Mercian Regiment Association inexorably to a close, it has been difficult to find any positives to (MRA) front to keep members informed of what the Colonel of highlight 2015. There has been the odd flurry of sporting success, the Regiment (CoR) envisages of the antecedent Regimental mixed with the inevitable failures, but other than that I suspect that Associations. many of you will not look back on the year with much fondness. It is rather assumed that in the fullness of time (10 years!) the The recent tragic events in Egypt, Beirut and Paris will have MRA will have absorbed all other association branches. The focused everyone on the catastrophe that is the Middle-East. Let move to this natural conclusion will be gradual with no outside us hope that this does not result in our politicians repeating their influence being applied. The operating rules of the MRA are previous mistakes, although history does not give cause for being finalised. These do not differ in any fundamental regard optimism. from the rules of the CRA. Once accepted by the CoR, two steps It was interesting to observe that there has recently been a towards the “natural conclusion” will be put in place, namely; drive in order to recruit more officers to our ever dwindling Army. I may be missing something, but with the total numbers in 1.