Two Peculiar Fast Transients in a Strongly Lensed Host Galaxy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY08 Technical Papers by GSMTPO Staff

AURA/NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation July 23, 2008 Revised as Complete and Submitted December 23, 2008 NGC 660, ~13 Mpc from the Earth, is a peculiar, polar ring galaxy that resulted from two galaxies colliding. It consists of a nearly edge-on disk and a strongly warped outer disk. Image Credit: T.A. Rector/University of Alaska, Anchorage NATIONAL OPTICAL ASTRONOMY OBSERVATORY NOAO ANNUAL REPORT FY 2008 Submitted to the National Science Foundation December 23, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 1 1 SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES AND FINDINGS ..................................................................................... 2 1.1 Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory...................................................................................... 2 The Once and Future Supernova η Carinae...................................................................................................... 2 A Stellar Merger and a Missing White Dwarf.................................................................................................. 3 Imaging the COSMOS...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Hubble Constant from a Gravitational Lens.............................................................................................. 4 A New Dwarf Nova in the Period Gap............................................................................................................ -

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science

The Impact of the Astro2010 Recommendations on Variable Star Science Corresponding Authors Lucianne M. Walkowicz Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley [email protected] phone: (510) 642–6931 Andrew C. Becker Department of Astronomy, University of Washington [email protected] phone: (206) 685–0542 Authors Scott F. Anderson, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Joshua S. Bloom, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Leonid Georgiev, Universidad Autonoma de Mexico Josh Grindlay, Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Steve Howell, National Optical Astronomy Observatory Knox Long, Space Telescope Science Institute Anjum Mukadam, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Andrej Prsa,ˇ Villanova University Joshua Pepper, Villanova University Arne Rau, California Institute of Technology Branimir Sesar, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nicole Silvestri, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Nathan Smith, Department of Astronomy, University of California Berkeley Keivan Stassun, Vanderbilt University Paula Szkody, Department of Astronomy, University of Washington Science Frontier Panels: Stars and Stellar Evolution (SSE) February 16, 2009 Abstract The next decade of survey astronomy has the potential to transform our knowledge of variable stars. Stellar variability underpins our knowledge of the cosmological distance ladder, and provides direct tests of stellar formation and evolution theory. Variable stars can also be used to probe the fundamental physics of gravity and degenerate material in ways that are otherwise impossible in the laboratory. The computational and engineering advances of the past decade have made large–scale, time–domain surveys an immediate reality. Some surveys proposed for the next decade promise to gather more data than in the prior cumulative history of astronomy. -

Whole Earth Telescope Observations of AM Canum Venaticorum – Discoseismology at Last

Astron. Astrophys. 332, 939–957 (1998) ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS Whole Earth Telescope observations of AM Canum Venaticorum – discoseismology at last J.-E. Solheim1;14, J.L. Provencal2;15, P.A. Bradley2;16, G. Vauclair3, M.A. Barstow4, S.O. Kepler5, G. Fontaine6, A.D. Grauer7, D.E. Winget2, T.M.K. Marar8, E.M. Leibowitz9, P.-I. Emanuelsen1, M. Chevreton10, N. Dolez3, A. Kanaan5, P. Bergeron6, C.F. Claver2;17, J.C. Clemens2;18, S.J. Kleinman2, B.P. Hine12, S. Seetha8, B.N. Ashoka8, T. Mazeh9, A.E. Sansom4;19, R.W. Tweedy4, E.G. Meistasˇ 11;13, A. Bruvold1, and C.M. Massacand1 1 Nordlysobservatoriet, Institutt for Fysikk, Universitetet i Tromsø, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway 2 McDonald Observatory and Department of Astronomy, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA 3 Observatoire Midi–Pyrenees, 14 Avenue E. Belin, F-31400 Toulouse, France 4 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK 5 Instituto de Fisica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 91500-970 Porto Alegre - RS, Brazil 6 Department de Physique, Universite´ de Montreal,´ C.P. 6128, Succ A., Montreal,´ PQ H3C 3J7, Canada 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Arkansas, 2801 S. University Ave, Little Rock, AR 72204, USA 8 Technical Physics Division, ISRO Satelite Centre, Airport Rd, Bangalore, 560 017 India 9 University of Tel Aviv, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel 10 Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, F-92195 Meudon Principal Cedex, France 11 Institute of Material Research and Applied Sciences, Vilnius University, Ciurlionio 29, Vilnius 2009, Lithuania 12 NASA Ames Research Center, M.S. -

1000 Cataclysmic Variables from the Catalina Real-Time Transient Survey

MNRAS 443, 3174–3207 (2014) doi:10.1093/mnras/stu1377 1000 cataclysmic variables from the Catalina Real-time Transient Survey E. Breedt,1‹ B. T. Gansicke,¨ 1 A. J. Drake,2 P. Rodr´ıguez-Gil,3,4 S. G. Parsons,5 T. R. Marsh,1 P. Szkody,6 M. R. Schreiber5 and S. G. Djorgovski2 1Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK 2California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd, CA 91225, USA 3Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Canarias, V´ıa Lactea´ s/n, La Laguna, E-38205, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain 4Departamento de Astrof´ısica, Universidad de La Laguna, La Laguna, E-38206, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain 5Instituto de F´ısica y Astronom´ıa, Universidad de Valpara´ıso, Avenida Gran Bretana 1111, 2360102 Valpara´ıso, Chile 6Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, Box 351580, Seattle, WA 98195-1580, USA Downloaded from Accepted 2014 July 6. Received 2014 July 5; in original form 2014 May 13 ABSTRACT Over six years of operation, the Catalina Real-time Transient Survey (CRTS) has identified http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/ 1043 cataclysmic variable (CV) candidates – the largest sample of CVs from a single survey to date. Here, we provide spectroscopic identification of 85 systems fainter than g ≥ 19, including three AM Canum Venaticorum binaries, one helium-enriched CV, one polar and one new eclipsing CV. We analyse the outburst properties of the full sample and show that it contains a large fraction of low-accretion-rate CVs with long outburst recurrence times. We argue that most of the high-accretion-rate dwarf novae in the survey footprint have already been found and that future CRTS discoveries will be mostly low-accretion-rate systems. -

SAS-2019 the Symposium on Telescope Science

Proceedings for the 38th Annual Conference of the Society for Astronomical Sciences SAS-2019 The Symposium on Telescope Science Joint Meeting with the Center for Backyard Astrophysics Editors: Robert K. Buchheim Robert M. Gill Wayne Green John C. Martin John Menke Robert Stephens May, 2019 Ontario, CA i Disclaimer The acceptance of a paper for the SAS Proceedings does not imply nor should it be inferred as an endorsement by the Society for Astronomical Sciences of any product, service, method, or results mentioned in the paper. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and may not reflect those of the Society for Astronomical Sciences, its members, or symposium Sponsors Published by the Society for Astronomical Sciences, Inc. Rancho Cucamonga, CA First printing: May 2019 Photo Credits: Front Cover: NGC 2024 (Flame Nebula) and B33 (Horsehead Nebula) Alson Wong, Center for Solar System Studies Back Cover: SA-200 Grism spectrum of Wolf-Rayet star HD214419 Forrest Sims, Desert Celestial Observatory ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE v SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS vi SYMPOSIUM SCHEDULE viii PRESENTATION PAPERS Robert D. Stephens, Brian D. Warner THE SEARCH FOR VERY WIDE BINARY ASTEROIDS 1 Tom Polakis LESSONS LEARNED DURING THREE YEARS OF ASTEROID PHOTOMETRY 7 David Boyd SUDDEN CHANGE IN THE ORBITAL PERIOD OF HS 2325+8205 15 Tom Kaye EXOPLANET DETECTION USING BRUTE FORCE TECHNIQUES 21 Joe Patterson, et al FORTY YEARS OF AM CANUM VENATICORIUM 25 Robert Denny ASCOM – NOT JUST FOR WINDOWS ANY MORE 31 Kalee Tock HIGH ALTITUDE BALLOONING 33 William Rust MINIMIZING DISTORTION IN TIME EXPOSED CELESTIAL IMAGES 43 James Synge PROJECT PANOPTES 49 Steve Conard, et al THE USE OF FIXED OBSERVATORIES FOR FAINT HIGH VALUE OCCULTATIONS 51 John Martin, Logan Kimball UPDATE ON THE M31 AND M33 LUMINOUS STARS SURVEY 53 John Morris CURRENT STATUS OF “VISUAL” COMET PHOTOMETRY 55 Joe Patterson, et al ASASSN-18EY = MAXIJ1820+070 = “MAXIE”: KING OF THE BLACK HOLE 61 SUPERHUMPS Richard Berry IMAGING THE MOON AT THERMAL INFRARED WAVELENGTHS 67 iii Jerrold L. -

Pos(HTRA-IV)023 , 1 , 9 , B.T

ULTRACAM observations of SDS 0926+3624: the first known eclipsing AM CVn star PoS(HTRA-IV)023 C.M. Copperwheat∗ Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK E-mail: [email protected] T.R. Marsh1, S.P. Littlefair2, V.S. Dhillon2, G. Ramsay3, A.J. Drake4, B.T. Gänsicke1, P.J. Groot5, P. Hakala6, D. Koester7, G. Nelemans5, G. Roelofs8, J. Southworth9, D. Steeghs1 and S. Tulloch2 1 Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL, UK 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, S3 7RH, UK 3 Armagh Observatory, College Hill, Armagh, BT61 9DG, UK 4 California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., CA 91225, USA 5 Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, Radboud University Nijmegen, PO Box 9010, NL-6500 GL Nijmegen, the Netherlands 6 Finnish Centre for Astronomy with ESO, Tuorla Observatory, Väisäläntie 20, FIN-21500 Piikkiö, University of Turku, Finland 7 Institut für Theoretische Physik und Astrophysik, Universität Kiel, 24098 Kiel, Germany 8 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 9 Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Newcastle-under-Lyme, ST5 5BG, UK The AM Canum Venaticorum (AM CVn) stars are ultracompact binaries with the lowest periods of any binary subclass, and consist of a white dwarf accreting material from a donor star that is it- self fully or partially degenerate. These objects offer new insight into the formation and evolution of binary systems, and are predicted to be among the strongest gravitational wave sources in the sky. To date, the only known eclipsing source of this type is the 28 min binary SDSS 0926+3624. -

Pos(Golden2015)001 † ∗ [email protected] [email protected] Speaker

The Golden Age of Cataclysmic Variables and Related Objects: The State of Art PoS(Golden2015)001 Franco Giovannelli∗† INAF - Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 100, 00133 Roma, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Lola Sabau-Graziati INTA- Dpt. Cargas Utiles y Ciencias del Espacio, C/ra de Ajalvir, Km 4 - E28850 Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain E-mail: [email protected] This paper is an extended and updated version of the reviews by Giovannelli (2008) and Giovan- nelli & Sabau-Graziati (2015a). In this paper we review cataclysmic variables (CVs) discussing several hot points about the renewing interest of today astrophysics about these sources. We will briefly discuss also about classical and recurrent novae, as well as the intriguing problem of progenitors of the Type Ia supernovae. However, the bulk of this paper consists in our attempt of studying CVs from the point of view of the magnetic field intensity (B) at the surface of their white dwarfs. Because of limited length of the paper and our knowledge, this review does not pretend to be complete. However, we would like to demonstrate that the improvement on knowledge of the physics of our Universe is strictly related also with the multifrequency behaviour of CVs, which apparently in the recent past lost to have a leading position in modern astrophysics. The Golden Age of Cataclysmic Variables and Related Objects - III, Golden2015 7-12 September 2015 Palermo, Italy ∗Speaker. †A footnote may follow. ⃝c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). -

Appendix C Common Abbreviations & Acronyms

C Common Abbreviations and Acronyms Michael A. Strauss This glossary of abbreviations used in this book is not complete, but includes most of the more common terms, especially if they are used multiple times in the book. We split the list into general astrophysics terms and the names of various telescopic facilities and surveys. General Astrophysical and Scientific Terms • ΛCDM: The current “standard” model of cosmology, in which Cold Dark Matter (CDM) and a cosmological constant (designated “Λ”), together with a small amount of ordinary baryonic matter, together give a mass-energy density sufficient to make space flat. Sometimes written as “LCDM”. • AAAS: American Association for the Advancement of Science. • AAVSO: American Association of Variable Star Observers (http://www.aavso.org). • ADDGALS: An algorithm for assigning observable properties to simulated galaxies in an N-body simulation. • AGB: Asymptotic Giant Branch, referring to red giant stars with helium burning to carbon and oxygen in a shell. • AGN: Active Galactic Nucleus. • AM CVn: An AM Canum Venaticorum star, a cataclysmic variable star with a particularly short period. • AMR: Adaptive Mesh Refinement, referring to a method of gaining dynamic range in the resolution of an N-body simulation. • APT: Automatic Photometric Telescope, referring to small telescopes appropriate for pho- tometric follow-up of unusual variables discovered by LSST. • BAL: Broad Absorption Line, a feature seen in quasar spectra. • BAO: Baryon Acoustic Oscillation, a feature seen in the power spectra of the galaxy distri- bution and in the fluctuations of the Cosmic Microwave Background. • BBN: Big-Bang Nucleosynthesis, whereby deuterium, helium, and trace amounts of lithium were synthesized in the first minutes after the Big Bang. -

Eric Agol – Bibliography

Eric Agol | Curriculum Vitae Department of Astronomy, Box 351580, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1580 Ó (206) 543-7106 • Q [email protected] • faculty.washington.edu/agol/ Professor of Astronomy, Adjunct Professor of Physics. Previous Employment University of Washington Seattle + Professor 2017 – present Department of Astronomy; Adjunct in Physics. University of Washington Seattle + Associate Professor 2009 –2017 University of Washington Seattle + Assistant Professor 2003 – 2009 Caltech Pasadena + Chandra Fellow 2000 – 2003 Johns Hopkins University Baltimore + Postdoctoral Fellow 1997 – 2000 Education Academic Qualifications................................................... ........................................... University of California Santa Barbara + PhD, Department of Physics, Astrophysics 1992–1997 University of California Berkeley + BA, Physics and Mathematics 1988–1992 Dissertation................................................... ................................................... ......... + ‘The Effects of Magnetic Fields, Absorption, and Relativity on the Polarization of Accretion Disks around Supermassive Black Holes.’ Advisor: Omer Blaes. Selected Research Accomplishments: + Created grid of models for Quasars (Hubeny, Agol et al. 2000; Agol 1997). + Computed optically-thin general-relativistic ray-tracing model, and proposed experiment for imaging the shadow of the Galactic Center black hole (Falcke, Melia & Agol 2000), which culminated in the Event Horizon Telescope. + Derived fast, analytic transit model for -

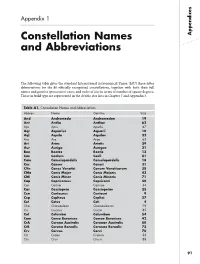

Constellation Names and Abbreviations Abbrev

09DMS_APP1(91-93).qxd 16/02/05 12:50 AM Page 91 Appendix 1 Constellation Names Appendices and Abbreviations The following table gives the standard International Astronomical Union (IAU) three-letter abbreviations for the 88 officially recognized constellations, together with both their full names and genitive (possessive) cases,and order of size in terms of number of square degrees. Those in bold type are represented in the double star lists in Chapter 7 and Appendix 3. Table A1. Constellation Names and Abbreviations Abbrev. Name Genitive Size And Andromeda Andromedae 19 Ant Antlia Antliae 62 Aps Apus Apodis 67 Aqr Aquarius Aquarii 10 Aql Aquila Aquilae 22 Ara Ara Arae 63 Ari Aries Arietis 39 Aur Auriga Aurigae 21 Boo Bootes Bootis 13 Cae Caelum Caeli 81 Cam Camelopardalis Camelopardalis 18 Cnc Cancer Cancri 31 CVn Canes Venatici Canum Venaticorum 38 CMa Canis Major Canis Majoris 43 CMi Canis Minor Canis Minoris 71 Cap Capricornus Capricorni 40 Car Carina Carinae 34 Cas Cassiopeia Cassiopeiae 25 Cen Centaurus Centauri 9 Cep Cepheus Cephei 27 Cet Cetus Ceti 4 Cha Chamaeleon Chamaeleontis 79 Cir Circinus Circini 85 Col Columba Columbae 54 Com Coma Berenices Comae Berenices 42 CrA Corona Australis Coronae Australis 80 CrB Corona Borealis Coronae Borealis 73 Crv Corvus Corvi 70 Crt Crater Crateris 53 Cru Crux Crucis 88 91 09DMS_APP1(91-93).qxd 16/02/05 12:50 AM Page 92 Table A1. Constellation Names and Abbreviations (continued) Abbrev. Name Genitive Size Cyg Cygnus Cygni 16 Appendices Del Delphinus Delphini 69 Dor Dorado Doradus 7 Dra Draco -

Two New AM Canum Venaticorum Binaries from the Sloan Digital Sky

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–6 (2013) Printed 24 September 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Two new AM Canum Venaticorum binaries from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey III P. J. Carter,1⋆ B. T. Gansicke,¨ 1 D. Steeghs,1 T. R. Marsh,1 E. Breedt,1 T. Kupfer,2 N. P. Gentile Fusillo,1 P. J. Groot2 and G. Nelemans2,3 1Department of Physics, University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, UK 2Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University Nijmegen, PO Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, the Netherlands 3Institute for Astronomy, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium Accepted/Received. ABSTRACT The AM Canum Venaticorum (AM CVn) binaries are a rare group of ultra-short period, mass- transferring white dwarf binaries, some of which may be Type Ia supernova progenitors. More than a third of the total known population of AM CVn binaries have been discovered via the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). Here, we discuss our search for new AM CVns in the SDSS spectroscopic data base, and present two new AM CVns discovered in SDSS-III spectroscopy, SDSS J113732.32+405458.3and SDSS J150551.58+065948.7.The AM CVn binaries exhibit a connection between their spectral appearance and their orbital period, the spectra of these two new AM CVns suggest that they may be long period systems. Using the radial velocity variations of the emission lines, we measure a possible orbital period of 59.6 ±2.7minutes for SDSSJ113732.32+405458.3.Since our search of SDSS spectroscopy has revealed only these two new systems, it is unlikely that a large population of AM CVn binaries have been missed, and their discovery should have little effect on previous calculations of the AM CVn space density. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism.