Official Judgment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Production Notes Greg Haddrick, Greg Mclean Nick Forward, Rob Gibson, Jo Rooney, Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS

A Stan Original Series presents A Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production, in association with Emu Creek Pictures financed with the assistance of Screen Australia and the South Australian Film Corporation Based on the feature films WOLF CREEK written, directed and produced by Greg McLean Adapted for television by Peter Gawler, Greg McLean & Felicity Packard Production Notes Greg Haddrick, Greg McLean Nick Forward, Rob Gibson, Jo Rooney, Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Felicity Packard SERIES WRITERS Tony Tilse & Greg McLean SERIES DIRECTORS As at 2.3.16 As at 2.3.16 TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Cast Page 3 Production Information Page 4 About Stan. and About Screentime Page 5 Series Synopsis Page 6 Episode Synopses Pages 7 to 12 Select Cast Biographies & Character Descriptors Pages 15 to 33 Key Crew Biographies Pages 36 to 44 Select Production Interviews Pages 46 to 62 2 KEY CAST JOHN JARRATT Mick Taylor LUCY FRY Eve Thorogood DUSTIN CLARE Detective Sergeant Sullivan Hill and in Alphabetical Order EDDIE BAROO Ginger Jurkewitz CAMERON CAULFIELD Ross Thorogood RICHARD CAWTHORNE Kane Jurkewitz JACK CHARLES Uncle Paddy LIANA CORNELL Ann-Marie RHONDDA FINDELTON Deborah ALICIA GARDINER Senior Constable Janine Howard RACHEL HOUSE Ruth FLETCHER HUMPHRYS Jesus (Ben Mitchell) MATT LEVETT Kevin DEBORAH MAILMAN Bernadette JAKE RYAN Johnny the Convict MAYA STANGE Ingrid Thorogood GARY SWEET Jason MIRANDA TAPSELL Constable Fatima Johnson ROBERT TAYLOR Roland Thorogood JESSICA TOVEY Kirsty Hill 3 PRODUCTION INFORMATION Title: WOLF CREEK Format: 6 X 1 Hour Drama Series Logline: Mick Taylor returns to wreak havoc in WOLF CREEK. -

Qatar, France Sign Pact for Strategic Dialogue

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Czech star Pliskova takes tough Vodafone Qatar schedule in posts QR118mn profi t in 2018 her stride published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11092 February 12, 2019 Jumada II 7, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets French FM Amir honours winners of state awards His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani honoured winners of the Qatar’s appreciative and incentive state awards in sciences, arts and literature. His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with French Minister The award winners were Dr Abdulaziz bin Abdullah Turki al-Subaie in the field of education, Mohamed Jassim al-Khulaifi (museums and archaeology), Dr Saif Saeed of Europe and Foreign Aff airs Jean-Yves Le Drian and his accompanying delegation Saif al-Suwaidi (economics), Dr Yousif Mohamed Yousif al-Obaidan (political science), Dr Hamad Abdulrahman al-Saad al-Kuwari (earth and environmental sciences), at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. The minister conveyed to the Amir the congratulations Mohanna Rashid al-Asiri al-Maadeed (earth and environmental sciences), Dr Huda Mohamed Abdullatif al-Nuaimi (allied medical sciences and nursing), Dr Asma of French President Emmanuel Macron on Qatar national football team winning the Ali Jassim al-Thani (allied medical sciences and nursing), Salman Ibrahim Sulaiman al-Malik (the art of caricature) and Abdulaziz Ibrahim al-Mahmoud in the novel 2019 Asian Cup. During the meeting, they reviewed bilateral relations and means of field. The Amir commended the winners’ distinguished performance, wishing them success in rendering services to the homeland. -

Fat Tony__Co Final D

A SCREENTIME production for the NINE NETWORK Production Notes Des Monaghan, Greg Haddrick Jo Rooney & Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler, Adam Todd, Jeff Truman & Michaeley O’Brien SERIES WRITERS Peter Andrikidis, Andrew Prowse & Karl Zwicky SERIES DIRECTORS MEDIA ENQUIRIES Michelle Stamper: NINE NETWORK T: 61 3 9420 3455 M: 61 (0)413 117 711 E: [email protected] IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTIFICATION TO MEDIA Screentime would like to remind anyone reporting on/reviewing the mini-series entitled FAT TONY & CO. that, given its subject matter, the series is complicated from a legal perspective. Potential legal issues include defamation, contempt of court and witness protection/name suppression. Accordingly there are some matters/questions that you may raise which we shall not be in a position to answer. In any event, please note that it is your responsibility to take into consideration all such legal issues in determining what is appropriate for you/the company who employs you (the “Company”) to publish or broadcast. Table of Contents Synopsis…………………………………………..………..……………………....Page 3 Key Players………….…………..…………………….…….…..……….....Pages 4 to 6 Production Facts…………………..…………………..………................Pages 7 to 8 About Screentime……………..…………………..…….………………………Page 9 Select Production & Cast Interviews……………………….…….…Pages 10 to 42 Key Crew Biographies……………………………………………...….Pages 43 to 51 Principal & Select Supporting Cast List..………………………………...….Page 52 Select Cast Biographies…………………………………………….....Pages 53 to 69 Episode Synopses………………………….………………….………..Pages 70 to 72 © 2013 Screentime Pty Ltd and Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd 2 SYNOPSIS FAT TONY & CO., the brand-new production from Screentime, tells the story of Australia’s most successful drug baron, from the day he quit cooking pizza in favour of cooking drugs, to the heyday of his $140 million dollar drug empire, all the way through to his arrest in an Athens café and his whopping 22-year sentence in Victoria’s maximum security prison. -

PDF Download Gangland Melbourne Ebook, Epub

GANGLAND MELBOURNE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Morton | 208 pages | 01 Oct 2011 | Melbourne University Press | 9780522858693 | English | Carlton, Australia Gangland Melbourne PDF Book EU leaders to discuss plans to roll-out Covid vaccine passports - while Britons who have received jabs will Ordinary Australians are being fined extortionate amounts for doing regular things like exercising outside for too long. News Home. Medical emergency involving flight crew member forces Virgin plane to return to Adelaide Posted 5 h hours ago Fri Friday 15 Jan January at am. Scottish Tories suspend candidate who claimed 'fat' foodbank users are 'far from starving' and accused Rebel Roundup Every Friday. The world's most popular perfume revealed: Carolina Herrerra's Good Girl is the most in demand across the Many of the murders remain unsolved, although detectives from the Purana Taskforce believe that Carl Williams was responsible for at least 10 of them. In the wake of the Informer scandal, Williams believed she could still get back the Primrose Street property, which was seized to repay her family's tax debt. May 8, - Lewis Caine, a convicted killer who had changed his name to Sean Vincent, shot dead and his body dumped in a back street in Brunswick. Never-before-seen photos of the St Kilda murder scene of an underworld figure have been released as part of a renewed police push for answers over the major event in the early years of Melbourne's gangland war. It is not allowed to happen,' she said. Boris Johnson and the Two Ronnies could be replaced by An edited version commenced screening in Victoria on 14 September Investigation concludes Joe the pigeon had a fake US leg band and won't be executed. -

HER HONOUR: > You Have Pleaded Guilty to the .Murder of Jason Moran

COR.1000.0004.0001_ER2_P HER HONOUR: i Mr Thomas i 1 1 ’ > you have pleaded guilty to the .murder of Jason Moran which occurred on 21 June 2003 in the Cross Keys Reserve in Pascoe Vale. The Crown position as stated by the Senior Crown Prosecutor, Mr Horgan SC, in respect of your plea is as follows: that Jason Moran and Pasquale Barbaro were shot dead in the carpark at the Cross Keys Reserve in Pascoe Vale on that date. They were in a van about to drive 1.0 children home from the Auskick football clinic, including the children of Jason Moran, The children were in thfe rear of i Mr McGrath ! the van. Mr Andrews had been driven to the reserve area byL-------- ! i Mr McGrath I I___________________ J who dropped him off near the van and drove off, approached the van and, using a shotgun, fired through the window of the van. He then dropped that weapon and used a hand gun pointed through the driver’s side window, aiming at the head of Jason Moran. Both Jason Moran, who was seated in the driver's side, and Pasquale Barbaro, who was in the passenger seat of the vehicle, were killed, 2 The Crown accepted for the purposes of your plea that the target for your attack was Jason Moran. Pasquale Barbaro was an unintended victim who was, as the prosecutor stated, "In the wrong place at the wrong time". 34 3 The background to this killing was the enmity between Carl Williams and the Morans, over the Morans' shooting of Williams in the stomach some years earlier. -

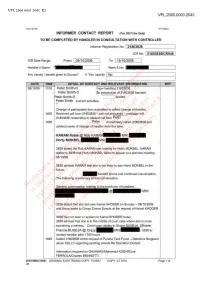

Redactions Have Been Applied by the Royal Commission in This Document

VPL.2000.0003.2043_R2 VPL.2000.0003.2043 New 07/05 VP1092A INFORMER CONTACT REPORT (For DSU Use Only) TO BE COMPLETED BY HANDLER IN CONSULTATION WITH CONTROLLER Informer Registration No: | 21803838 | ICR No: I 21803838ICR048 | ICR Date Range From: | 09/10/2006 | To: I 15/10/2006 | Handler’s Name: Rank & No: Any money! benefit given to Source? If ‘Yes’ specify No DATE TIME DETAIL OF CONTACT AND RELEVANT INFORMATION REF 09/10/06 1315 Peter Smith-0 | now handling 21803838. Peter Smith-0 |in possession ofCommission 21803838 handset. Peter Smith-0 _ _ _______ briefed Peter Smith Current activities. it including, Royal Change of participants form submitted to reflect changelegal of handler. 1405 Received call from 21803838 -the call not answered - message left. 21803838 responding to missed call from Peter 1405 byPeter reasonsimmediately called 21803838 and advised same of change of handler from this time. determined of immunity,non-publication KARAM Rabie @ Rob KARAM^^^Mof has legislative, Horty MOKBEL^^Happlied mNI^^^H numberinterest 3838 beenstated the a Rob KARAM was looking for Horty MOKBEL. KARAM stated to 3838 that Horty MOKBEL failed to appear at a planned meeting 08/10/06.for operation have public Commissionreputational, 3838 advisedto, KARAM that she is not likely to see Horty MOKBEL in the future. ________the on privilege, handed phone and continued conversation. documentThe following a summary of that conversation. limited wherebased reasons. Redactionsthis General conversation relating to the handover of handlers. not in and @ M N1: but safety professional3838 stated thator she last saw Kamel KHODER on Sunday - 08/10/2006 orders,andappropriate drove same to Crispy Creme Donuts at the request of Kamel KHODER. -

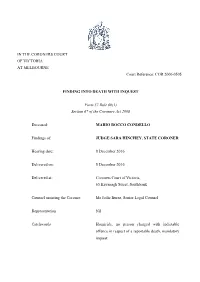

COR 2006 0505 FINDING INTO DEATH with INQUEST Form 37

IN THE CORONERS COURT OF VICTORIA AT MELBOURNE Court Reference: COR 2006 0505 FINDING INTO DEATH WITH INQUEST Form 37 Rule 60(1) Section 67 of the Coroners Act 2008 Deceased: MARIO ROCCO CONDELLO Findings of: JUDGE SARA HINCHEY, STATE CORONER Hearing date: 8 December 2016 Delivered on: 8 December 2016 Delivered at: Coroners Court of Victoria, 65 Kavanagh Street, Southbank Counsel assisting the Coroner: Ms Jodie Burns, Senior Legal Counsel Representation Nil Catchwords Homicide, no person charged with indictable offence in respect of a reportable death, mandatory inquest TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 1 The purpose of a coronial investigation 2 Victoria Police homicide investigation 3 Matters in relation to which a finding must, if possible, be made - Identity of the deceased 5 - Medical cause of death 5 - Circumstances in which the death occurred 6 Findings and conclusion 8 HER HONOUR: BACKGROUND 1 Mario Rocco Condello (Mr Condello) was born on 12 April 1952 at the Royal Women’s Hospital, Carlton to . Mr Condello had an older sister, , and a younger brother, . Mr Condello’s parents, who were originally from Italy, taught him to speak Calabrese, the primary language of the Southern Italian region of Calabria. 2 After leaving High School, Mr Condello commenced a law degree at Monash University, from which he graduated in 1976. In his final year of university Mr Condello met and commenced a relationship with and they married in 1978. 3 Also in 1978, Mr Condello commenced his own legal practice, ‘Mario Condello Solicitors’, in Best Street, North Fitzroy. During this period of time, North Fitzroy had a prominent Italian community and as a result, Mr Condello gained a number of Italian clients. -

Reaching for the Heights - Acclaimed Series the Heights Commissioned for a Second Season

RELEASED: MONDAY 19 AUGUST 2019 Reaching for the heights - acclaimed series The Heights commissioned for a second season Season one available now to binge on ABC iview Critically-acclaimed series The Heights will return to the ABC in 2020 with filming beginning this month in Perth, WA. Produced by Matchbox Pictures and For Pete’s Sake Productions for ABC, The Heights, received major production investment from Screenwest and Screen Australia. NBCUniversal International Studios will distribute the series. Announced today as a finalist in Drama Series Production of the Year category at the 19th Screen Producers Australia Awards, The Heights, season one, was a hit with critics and fans. The Guardian called it “a warm, complex and credible Australian soap opera,1” and an engaged and loyal viewer base unashamedly shared their praise on social media at #theheightstv. Season two will continue to showcase the life-affirming, family-friendly storytelling audiences have come to expect. As the show continues its balance of heart, humour and truth, we’ll see favourite characters continue to pull together to triumph over whatever life throws at them. Sally Riley, Head of Drama, Comedy and Indigenous for the ABC, said: “We’re thrilled to be working with Matchbox Pictures and For Pete’s Sake Productions to bring a second series to ABC audiences. Season One was warmly embraced by critics and audiences for reflecting real, complex and diverse Australian stories. We look forward to seeing what’s in store for the characters during these 30 new episodes.” -

Justice Betty �Ing: a Study of Feminist Judging in Action

UNSW Law Journal Volume 40(2) 13 JUSTICE BETTY ING: A STUDY OF FEMINIST JUDGING IN ACTION ROSEMARY HUNTER AND DANIELLE TYSON I INTRODUCTION Justice Betty King sat on the Supreme Court of Victoria for 10 years from 2005–15. Prior to that she was a judge of the Victorian County Court from 2000– 05 after a career at the Victorian Bar from 1975–2000. During her career she was a pioneer for women in many respects, being only the 24th woman called to the Victorian Bar, the first woman prosecutor in Victoria, the first woman Commonwealth prosecutor, and one of the first Victorian women appointed a C. 1 As a Supreme Court judge, Justice King was known for ‘speaking her mind’, her ‘no nonsense approach and colourful attire’.2 She gained a high profile in her role in the series of trials associated with the Melbourne gangland killings dramatised in the television series, Underbelly.3 She was the judge who banned the broadcast of Underbelly in Victoria during the murder trial of one of its protagonists, Carl Williams, 4 and she also banned a Today Tonight episode featuring a showdown between Carl Williams’ mother and the mother of Lewis Moran during the trial of Evangelos Goussis for Moran’s murder.5 In a May 2010 interview she spoke out against the media’s treatment of prominent defendants Professor of Law and Socio-Legal Studies, ueen Mary University of London. Senior Lecturer in Criminology, Deakin University. 1 Li Porter, ‘King of Her Court’, The Age (online), 18 November 2007 <http://www.theage.com.au/news/ in-depth/king-of-her-court/2007/11/17/1194767017489.html>; Stefanie Garber, ‘High-Profile Judge Betty King Retires’, Lawyers Weekly (online), 17 August 2015 <http://www.lawyersweekly.com.au/wig- chamber/16981-high-profile-judge-betty-king-retires>. -

© 2018 Mystery Road Media Pty Ltd, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Create NSW, Screenwest (Australia) Ltd, Screen Australia

© 2018 Mystery Road Media Pty Ltd, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Create NSW, Screenwest (Australia) Ltd, Screen Australia SUNDAYS AT 8.30PM FROM JUNE 3, OR BINGE FULL SEASON ON IVIEW Hotly anticipated six-part drama Mystery Road will debut on ABC & ABC iview on Sunday, 3 June at 830pm. Because just one episode will leave audiences wanting for more, the ABC is kicking off its premiere with a special back-to-back screening of both episodes one and two, with the entire series available to binge on iview following the broadcast. Contact: Safia van der Zwan, ABC Publicist, 0283333846 & [email protected] ABOUT THE PRODUCTION Filmed in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, Aaron Pedersen and Judy Davis star in Mystery Road – The Series a six part spin-off from Ivan Sen’s internationally acclaimed and award winning feature films Mystery Road and Goldstone. Joining Pedersen and Davis is a stellar ensemble casting including Deborah Mailman, Wayne Blair, Anthony Hayes, Ernie Dingo, John Waters, Madeleine Madden, Kris McQuade, Meyne Wyatt, Tasia Zalar and Ningali Lawford-Wolf. Directed by Rachel Perkins, produced by David Jowsey & Greer Simpkin, Mystery Road was script produced by Michaeley O’Brien, and written by Michaeley O’Brien, Steven McGregor, Kodie Bedford & Tim Lee, with Ivan Sen & the ABC’s Sally Riley as Executive Producers. Bunya Productions’ Greer Simpkin said: “It was a great honour to work with our exceptional cast and accomplished director Rachel Perkins on the Mystery Road series. Our hope is that the series will not only be an entertaining and compelling mystery, but will also say something about the Australian identity.” ABC TV Head of Scripted Sally Riley said: “The ABC is thrilled to have the immense talents of the extraordinary Judy Davis and Aaron Pedersen in this brand new series of the iconic Australian film Mystery Road. -

Will Jones Stunt Actor

WILL JONES STUNT ACTOR PROFILE Will decided he would be a stunt man at the age of 12, since watching far too many Jackie Chan movies and meeting Xena’s stunt double, Zoë Bell. He started Gymnastics when he was 7 years old and later took up Trampolining, Tumbling and Kickboxing, training he continues to this day. Will’s ongoing commitment and training in all these fields led him to becoming a professional stunt performer at the young age of 20 in 2007. Since then, he has honed his skills, especially in the area of on screen fighting. Will is also a keen actor and filmmaker. MEAA # 3009672 AUSTRALIAN STUNT MANAGEMENT Agent | Louise Brown P: + 613 9682 9299 M: +61 (0)425 713 246 F: +613 9682 9455 E: [email protected] W: www.australianstuntmanagement.com.au FILMS CREDITS | STUNTS • Blacklight 2021 Feature (US/AUS) SD/D • Verite (Independent) 2019 Feature SP/A • Winchester 2017 Feature SP • Holding the Man 2014 Feature SP/A • The Hobbit: Battle of Five Armies 2013 Feature SP • I Frankenstein 2012 Feature (US/AUS) SP • John Doe 2011 Feature SP • The Cup 2010 Feature SP • The Loved Ones 2008 Feature SP/D • Knowing 2008 Feature (US/AUS) SP/D TELEVISION CREDITS | STUNTS • La Brea 2021 TV Series (US/AUS) SP/D • Bloom 2019 TV Series SP/A licences/ interests measurements skills Car Gymnastics/ HEIGHT 6' 4'' 193 cm SP| STUNT PERFORMER Motorbike Acrobatics CHEST 39'' 99 cm R | STUNT RIGGER Trampolining WAIST 31'' 78.7cm D | DRIVER Martial Arts HIPS 38'' 96.5 cm A | ACTOR HEAD 23'' 58.4 cm NECK 16'' 40 cm I/LEG 33.5'' 85 cm O/LEG -

Nowhere Boys: the Book of Shadows, Mini-Series Seven Types of Ambiguity, and Barracuda

Introduction The wait is over…Australia’s award-winning drama series Glitch returns to ABC, Thursday 14 September at 8.30pm with all episodes stacked and available to binge watch on ABC iview. When it first premiered in 2015, Glitch broke the mold and garnered fans around the country, who became immersed in the story of the Risen - the seven people who returned from the dead in perfect health. With no memory of their identities, disbelief soon gave way to a determination to discover who they are and what happened to them. Featuring a stellar cast including: Patrick Brammall, Emma Booth, Emily Barclay, Rodger Corser, Genevieve O’Reilly, Sean Keenan, Rob Collins and Hannah Monson, Glitch is an epic paranormal saga about love, loss and what it means to be human, and the dark secrets that lie beneath our country’s history. Season two picks up with James (Patrick Brammall), dealing with his recovering wife, Sarah (Emily Barclay) and a new-born baby daughter. He continues to be committed to helping the remaining Risen unravel the mystery of how and why they have returned and shares with them his discovery that Doctor Elishia Mackeller (Genevieve O’Reilly), now missing, died and came back to life four years ago and has been withholding many secrets from the beginning. Meanwhile on the run and desperate, John Doe (Rodger Corser) crosses paths with the mysterious Nicola Heysen (Pernilla August) head of Noregard Pharmaceuticals. Sharing explosive information with him, she convinces him that that the only way to discover answers to his questions is to offer himself up for testing inside their facility.