Robot History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premiere Props • Hollyw Ood a Uction Extra Vaganza VII • Sep Tember 1 5

Premiere Props • Hollywood Auction Extravaganza VII • September 15-16, 2012 • Hollywood Live Auctions Welcome to the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza weekend. We have assembled a vast collection of incredible movie props and costumes from Hollywood classics to contemporary favorites. From an exclusive Elvis Presley museum collection featured at the Mississippi Music Hall Of Fame, an amazing Harry Potter prop collection featuring Harry Potter’s training broom and Golden Snitch, to a entire Michael Jackson collection featuring his stage worn black shoes, fedoras and personally signed items. Plus costumes and props from Back To The Future, a life size custom Robby The Robot, Jim Carrey’s iconic mask from The Mask, plus hundreds of the most detailed props and costumes from the Underworld franchise! We are very excited to bring you over 1,000 items of some of the most rare and valuable memorabilia to add to your collection. Be sure to see the original WOPR computer from MGM’s War Games, a collection of Star Wars life size figures from Lucas Film and Master Replicas and custom designed costumes from Bette Midler, Kate Winslet, Lily Tomlin, and Billy Joel. If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of our staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza V II live event and we look forward to seeing you on October 13-14 for Fangoria’s Annual Horror Movie Prop Live Auction. -

Rethinking the Fourth Amendment in the Age of Supercomputers, Artificial Intelligence, and Robots

Volume 119 Issue 3 Article 4 April 2017 Rethinking the Fourth Amendment in the Age of Supercomputers, Artificial Intelligence, and Robots Melanie Reid Lincoln Memorial University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Fourth Amendment Commons, Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Melanie Reid, Rethinking the Fourth Amendment in the Age of Supercomputers, Artificial Intelligence, and Robots, 119 W. Va. L. Rev. (2017). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol119/iss3/4 This 2017 Evolving Investigative Technologies and the Law Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reid: Rethinking the Fourth Amendment in the Age of Supercomputers, Art RETHINKING THE FOURTH AMENDMENT IN THE AGE OF SUPERCOMPUTERS, ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, AND ROBOTS by Melanie Reid* I. IN TRODU CTION ............................................................................. 864 II. M EET OFFICER "JOE ROBOTO". ................................................... 868 A. Issue #1: Officer Joe Roboto Will Be Smarter, Faster,and More Efficient than Its Human Counterparts....................... 871 B. Issue #2: Officer Joe Roboto Signifies a GreaterIntrusion into Our P rivate L ives .................................................................. 872 C. Issue #3: Officer Joe Roboto's Easy Access to an Endless DatabaseRequires a Complete Rethinking of CurrentFourth A m endment D octrine ............................................................ 873 III. A TYPICAL DAY IN THE LIFE OF OFFICER JOE ROBOTO .............. -

44 Th Series of SPP (2020

KARNATAKA STATE COUNCIL FOR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Indian Institute of Science Campus, Bengaluru – 560 012 Website: http://www.kscst.iisc.ernet.in/spp.html || Email: [email protected] || Phone: 080-23341652, 23348840/48/49 44th Series of Student Project Programme: 2020-21 List of Student Project Proposals Approved for Sponsorship 1. A.C.S. COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, BENGALURU Sl. PROJECT PROJECT TITLE BRANCH COURSE NAME OF THE NAME OF THE STUDENT(S) SANCTIONED No. REFERENCE No. GUIDE(S) AMOUNT (IN Rs.) 1. 44S_BE_1382 FACE MASK DETECTION SYSTEM FOR THE ERA OF COVID-19 USING MACHINE COMPUTER B.E. Prof. POONAM Ms. BHAVANA G 2500.00 LEARNING TECHNIQUES SCIENCE AND KUMARI Ms. CHAITANYASHREE ENGINEERING Ms. KEERTHI L N 2. 44S_BE_1385 IOT BASED UNIT FOR COPD TREATMENT BIOMEDICAL B.E. Dr. ANITHA S Ms. RASHMI S 5500.00 ENGINEERING Ms. POOJA D 3. 44S_BE_1386 PILLBOT: A NONCONTACT MEDICINE DISPENSING ROBOT FOR PATIENTS IN BIOMEDICAL B.E. Prof. NANDITHA Ms. SHEETAL RAMESH 5000.00 QUARANTINE ENGINEERING KRISHNA Ms. R NAVYA SREE Ms. RAJESHWARI SAJITH Mr. S KOSAL RAMJI 4. 44S_BE_3064 PAIN RELIEF DEVICE FOR THE TREATMENT OF MIGRAINE BIOMEDICAL B.E. Prof. HEMANTH Ms. SHREYA CHAKRAVARTHY 5000.00 ENGINEERING KUMAR G Ms. M VAGDEVI Ms. SHREE GOWRI M H Ms. SPOORTHI N K 5. 44S_BE_3066 FABRICATION OF SHEET METAL CUTTING MACHINE AND FOOT STEP POWER MECHANICAL B.E. Prof. SUNIL RAJ B A Mr. LOHITH M C 7000.00 GENERATION ENGINEERING Mr. NITISH G Mr. VINOD KUMAR K Mr. ANIL KUMAR 6. 44S_BE_4243 INTEGRATION OF BIODEGRADABLE COMPOSITES IN AIRCFART STRUCTURES AERONAUTICAL B.E. -

Forbidden Planet: Film Score for Full Orchestra

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 12-2003 Forbidden Planet: Film Score for Full Orchestra Tim Perrine Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Composition Commons Recommended Citation Perrine, Tim, "Forbidden Planet: Film Score for Full Orchestra" (2003). Graduate Thesis Collection. 400. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/400 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Name of candidate: (111f:£tz£Zt8\lf:.- ····························································································· Oral examination: Date ..................... l.. ? ....... 1J?.g~.~.?.~.~ ..... ?:gO 3 Committee: Thesis title: .......... f .. O..~.~. .LP..P.f .. N. ......1?.~~g.) ······················'91 () (6"~$f:F,._ ............. · Thesis approved in final form: Date ................ }..fJ... ..... P.£..~.J?~...... '?:PP.~ ........ Major Professor .. ........ ........ z.{;:.f:VF.~f.f?.- STRANGE PLANET ~ FAMILIAR SOUNDS RE-SCORING FORBIDDEN PLANET Tim Perrine, 2003 Master,s Thesis Paper Prologue The intent of my master's thesis is two-fold. First, I wanted to present a large- scale work for orchestra that showcased the skills and craft I have developed as a composer (and orchestrator) to date. Secondly, since my goal as a composer is to work in Hollywood as a film composer, I wanted my large-scale work to function as a film score, providing the emotional backbone and highlighting action for a major motion picture. In order to achieve this, I needed a film that was both larger-than-life and contained, in my opinion, an easily replaceable score (or no score at all). -

Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction

“Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction By Dr. John L. Flynn While most critics tend to regard “Forbidden Planet” (1956) as a futuristic retelling of William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”—with Morbius as Prospero, Robby the Robot as Arial, and the Id monster as the evil Caliban—this very conventional approach overlooks the most obvious. “Forbidden Planet” was, in fact, pulp science fiction, a conglomeration of every cliché and melodramatic element from the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s. With its mysterious setting on an alien world, its stalwart captain and blaster-toting crew, its mad scientist and his naïve yet beautiful daughter, its indispensable robot, and its invisible monster, the movie relied on a proven formula. But even though director Fred Wilcox and scenarist Cyril Hume created it on a production line to compete with the other films of its day, “Forbidden Planet” managed to transcend its pulp origins to become something truly memorable. Today, it is regarded as one of the best films of the Fifties, and is a wonderful counterpoint to Robert Wise’s “The Day the Earth Stood Still”(1951). The Golden Age of Science Fiction is generally recognized as a twenty-year period between 1926 and 1946 when a handful of writers, including Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, Isaac Asimov, John W. Campbell, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Frederick Pohl, and L. Ron Hubbard, were publishing highly original, science fiction stories in pulp magazines. While the form of the first pulp magazine actually dates back to 1896, when Frank A. Munsey created The Argosy, it wasn’t until 1926 when Hugo Gernsback published the first issue of Amazing Stories that science fiction had its very own forum. -

Robot Control and Programming: Class Notes Dr

NAVARRA UNIVERSITY UPPER ENGINEERING SCHOOL San Sebastian´ Robot Control and Programming: Class notes Dr. Emilio Jose´ Sanchez´ Tapia August, 2010 Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra 987‐84‐8081‐293‐1 ii Viaje a ’Agra de Cimientos’ Era yo todav´ıa un estudiante de doctorado cuando cayo´ en mis manos una tesis de la cual me llamo´ especialmente la atencion´ su cap´ıtulo de agradecimientos. Bueno, realmente la tesis no contaba con un cap´ıtulo de ’agradecimientos’ sino mas´ bien con un cap´ıtulo alternativo titulado ’viaje a Agra de Cimientos’. En dicho capitulo, el ahora ya doctor redacto´ un pequeno˜ cuento epico´ inventado por el´ mismo. Esta pequena˜ historia relataba las aventuras de un caballero, al mas´ puro estilo ’Tolkiano’, que cabalgaba en busca de un pueblo recondito.´ Ya os podeis´ imaginar que dicho caballero, no era otro sino el´ mismo, y que su viaje era mas´ bien una odisea en la cual tuvo que superar mil y una pruebas hasta conseguir su objetivo, llegar a Agra de Cimientos (terminar su tesis). Solo´ deciros que para cada una de esas pruebas tuvo la suerte de encontrar a una mano amiga que le ayudara. En mi caso, no voy a presentarte una tesis, sino los apuntes de la asignatura ”Robot Control and Programming´´ que se imparte en ingles.´ Aunque yo no tengo tanta imaginacion´ como la de aquel doctorando para poder contaros una historia, s´ı que he tenido la suerte de encontrar a muchas personas que me han ayudado en mi viaje hacia ’Agra de Cimientos’. Y eso es, amigo lector, al abrir estas notas de clase vas a ser testigo del final de un viaje que he realizado de la mano de mucha gente que de alguna forma u otra han contribuido en su mejora. -

Downloaded,” and Galen Tryol Has a Son, Nicholas, with His Human Wife, Cally, When the Couple Lives on the Planet New Caprica

DISTRIBUTION AGREEMENT In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in who or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation ____________________________________ July 16, 2014__________ Sarah Toton Date From Mechanical Men to Cybernetic Skin-Jobs: A History of Robots in American Popular Culture By Sarah Toton Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts ________________________________________________ Cristine Levenduski, Ph.D. Co-Chair ________________________________________________ Kevin Corrigan, Ph.D. Co-Chair ________________________________________________ Ted Friedman, Ph.D. Outside Co-Chair ________________________________________________ Karla Oeler, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ________________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies _______________________ Date ! From Mechanical Men to Cybernetic Skin-Jobs: A History of Robots in American Popular Culture -

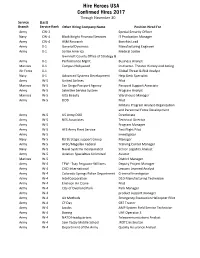

30 Nov Hires Report

Hire Heroes USA Confirmed Hires 2017 Through November 30 Service (Last) Branch Service Rank Other Hiring Company Name Position Hired For Army CW-2 Special Security Officer Navy CW-4 Black Knight Financial Services IT Production Manager Army CW-4 ASM Research Benefits Lead Army 0-1 General Dynamics Manufacturing Engineer Army 0-1 Scribe America Medical Scribe Gwinnett County Office of Strategy & Army 0-1 Performance Mgmt. Business Analyst Marines 0-1 Campus Hollywood Instructor- Theater History and Acting Air Force 0-1 Global Threat & Risk Analyst Navy 0-1 Advanced Systems Development Help Desk Specialist Army W-5 United Airlines Pilot Marines W-5 San Diego Passport Agency Passport Support Associate Army W-5 Selective Service System Program Analyst Marines W-5 Ulta Beauty Warehouse Manager Army W-5 DOD Pilot Military Program Analyst-Organization and Personnel Force Development Army W-5 US Army DOD Directorate Army W-5 NES Associates Technical Director Army W-5 Program Manager Army W-5 AFS Army Fleet Service Test Flight Pilot Army W-5 Investigator Navy W-5 R3 Strategic support Group Manager Army W-5 AFSC/Magellan Federal Training Center Manager Navy W-5 Naval Systems Incorporated Senior Logistics Analyst Army W-5 Aviation Specialties Unlimited Aviator Marines W-5 District Manager Army W-4 TFW - Tsay Ferguson-Williams Deputy Project Manager Army W-4 CACI International Lessons Learned Analyst Army W-4 Colorado Springs Police Department Criminal Investigator Army W-4 Intel Corporation D1D Manufacturing Technician Army W-4 Erickson Air Crane -

Team Runswift University of New South Wales, Australia

Team rUNSWift University of New South Wales, Australia RoboCup 2017 Standard Platform League Gary Bai, Sean Brady, Kenji Brameld, Amri Chamela, Jeremy Collette, Samuel Collis-Bird, Kirsten Hendriks, Ethan Jones, Liangde Li, Alvin Prijatna, Peter Schmidt, Hayden Smith, Addo Wondo, Victor Wong, Maurice Pagnucco, Brad Hall, Timothy Wiley, and Claude Sammut School of Computer Science and Engineering University of New South Wales Sydney 2052 Australia http://www.cse.unsw.edu.au Abstract. RoboCup inspires and motivates our research interests in cognitive robotics and machine learning, especially vision, state-estimation, locomotion, layered hybrid architectures, and high-level programming languages. The 2017 rUNSWift team comprises final year undergradu- ate honours students, Master and PhD students, past RoboCup students and supervisors who have been involved in RoboCup for over a decade. New developments in 2017 include increased density foveation, a vision architecture change, a new ball and goal classifier, improved localising techniques, and development of both web-based and non-web based test- ing platforms. 1 The Team The RoboCup Standard Platform League (SPL) is an excellent training ground. Participant team members need to collaborate on the development of a highly complex software system, deliver it on time, and within budget. This year the UNSW SPL team comprises a mix of undergraduate, masters and PhD students, both past and present. By participating in RoboCup the team is engaged in a unique educational experience and makes a significant contribution towards research, as is evident from the list of references at the end of this article. The 2017 rUNSWift team members are Gary Bai, Sean Brady, Kenji Brameld, Amri Chamela, Samuel Collis-Bird, Kirsten Hendriks, Ethan Jones, Alvin Pri- jatna, Peter Schmidt, Hayden Smith, Liangde Li, Addo Wondo, Victor Wong, Brad Hall, Timothy Wiley, Maurice Pagnucco, and Claude Sammut. -

Malachy Eaton Evolutionary Humanoid Robotics Springerbriefs in Intelligent Systems

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, MULTIAGENT SYSTEMS, AND COGNITIVE ROBOTICS Malachy Eaton Evolutionary Humanoid Robotics SpringerBriefs in Intelligent Systems Artificial Intelligence, Multiagent Systems, and Cognitive Robotics Series editors Gerhard Weiss, Maastricht, The Netherlands Karl Tuyls, Liverpool, UK More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11845 Malachy Eaton Evolutionary Humanoid Robotics 123 Malachy Eaton Department of Computer Science and Information Systems University of Limerick Limerick Ireland ISSN 2196-548X ISSN 2196-5498 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Intelligent Systems ISBN 978-3-662-44598-3 ISBN 978-3-662-44599-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-44599-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2014959413 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © The Author(s) 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Build the T-800 1:2 Scale

PACK 11 BUILD THE T-800 1:2 SCALE The Most Legendary cyborg In Science Fiction History! T1, THE TERMINATOR, ENDOSKELETON, and any depiction of Endoskeleton are trademarks of STUDIOCANAL S.A.S. All Rights Reserved. © 2020 STUDIOCANAL S.A.S. ® All Rights Reserved. 2 T-800 ASSEMBLY BUILD THE T-800 PACK 11 CONTENTS T-800 ASSEMBLY: STAGES 101–110 STAGE 101: ATTACH THE LEFT FOOT, AND BEGIN CONSTRUCTION ON THE CHEST ... 3 STAGE 102: DETAIL THE HEAD, AND ADD PANELS AND SPRINGS TO THE CHEST.......7 STAGE 103: AFFIX THE CHEST ASSEMBLY AND ATTACH SPRING TUBE DETAILS .......11 STAGE 104: GLUE THE CHEST SUPPORTS INTO PLACE, AND ASSEMBLE AND AFFIX A LARGE BACK PANEL .......................................................................................15 STAGE 105: FIT BACK PANEL DETAIL AND ATTACH SHOULDER CONNECTORS.........19 STAGE 106: INSTALL THE CIRCUIT BOARD........................................................................ 23 STAGE 107: CONNECT THE BATTERY, ATTACH THE BACK OF THE HEAD, AND FIT AN LED INTO ITS HOUSING ..........................................................................25 STAGE 108: AFFIX ROCK DETAILS AND SEARCHLIGHT TO THE FIRST BASE SECTION ........29 STAGE 109: BUILD A SECOND SEARCHLIGHT AND ADD A BASE DETAIL. ..................33 STAGE 110: CONNECT A SECOND BASE SECTION TO THE FIRST, AND APPLY DETAILS ..37 SCI-FI CINEMA: CYBORGS AND ROBOTS ................................ 41 REAL-WORLD SCIENCE ............................................................ 44 IDENTIFYING YOUR COMPONENTS: Each of your Terminator packs is divided into stages. Each stage contains a number of components, and can be identified by referring to the images in your assembly guide or the number located on the sticker on the back of each stage. Each number begins with ‘77’ and is followed by a further three digits. -

Challenges for Dialog in Human-Robot Interaction

Challenges for Dialog in Human-Robot Interaction Dialogs on Dialogs Meeting October 7 th 2005 Hartwig Holzapfel 1 Challenges for Dialog in Human-Robot Interaction Hartwig Holzapfel SFB 588 About me • Studied Computer Science in Karlsruhe (Germany) • Minor field of study Computational Linguistics Stuttgart (Germany) • Diploma Thesis on Emotion-Sensitive Dialogue at ISL, Prof. Waibel • Scientific employee/PhD student at Karlsruhe/Prof. Waibel since 2003 • Recent Projects – FAME: EU Project: Facilitating Agents for Multicultural Exchange presented at Barcelona Forum/ACL 2004 – SFB 588: collaborative research effort at Karlsruhe on Humanoid Robots • Research (within above projects): – Multimodal (speech+pointing synchronous and fleximodal) – Multilingual Aspects – ASR in dialogue context – Current: Cognitive Architecture for Robots and Learning 2 Challenges for Dialog in Human-Robot Interaction Hartwig Holzapfel SFB 588 Outline • Robots • SFB588: The humanoid-Robots project • The Robot „Armar“ • Interaction scenarios • Multimodal Interaction • Multilingual Speech Processing • Cognitive Architectures • Open Tasks 3 Challenges for Dialog in Human-Robot Interaction Hartwig Holzapfel SFB 588 Humanoid Robots • Why humanoid: – Humanoid body facilitates acting in a world designed for humans – Use Tools designed for humans – Interaction with humans – Intuitive multimodal communication – Other aspecs like understand human intelligence • Kind of Humanoid Robots – Service Robots – Assistants – Space – Help for elderly persons 4 Challenges for Dialog