The Longest Day Dawns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 ©

© 2018 Dublin City Council City Dublin 2018 © This Map & Guide was produced by Dublin City Council in partnership with Portobello Residents Group. Special thanks to Ciarán Breathnach for research and content. Thanks also to the following for their contribution to the Portobello Walking Trail: Anthony Freeman, Joanne Freeman, Pat Liddy, Canice McKee, Fiona Hayes, Historical Picture Archive, National Library of Ireland and Dublin City Library & Archive. Photographs by Joanne Freeman and Drew Cooke. For further reading on Portobello: ‘Portobello’ by Maurice Curtis and ‘Jewish Dublin: Portraits of Life by the Liffey’ by Asher Benson. For details on Dublin City Council’s programme of walking tours and weekly walking groups, log on to www.letswalkandtalk.ie For details on Pat Liddy’s Walking Tours of Dublin, log on to www.walkingtours.ie For details on Portobello Residents Group, log on to www.facebook.com/portobellodublinireland Design & Production: Kaelleon Design (01 835 3881 / www.kaelleon.ie) Portobello derives its name from a naval battle between Great Britain and Welcome to Portobello! This walking trail emigrated, the building fell into disuse and ceased functioning as a place of worship by Spain in 1739 when the settlement of Portobello on Panama’s Carribean takes you through “Little Jerusalem”, along the mid 1970s. The museum exhibits a large collection of memorabilia and educational displays relating to the Irish Jewish communities. Close by at 1 Walworth Road is the the Grand Canal and past the homes of many The original bridge over the Grand Canal was built in 1790. In 1936 it was rebuilt and coast was captured by the British. -

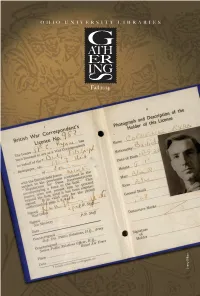

Gatherings, 2014 Fall

OHIO UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Fall 2014 Sherry DiBari From the Dean of the Libraries MINING THE CORNELIUS RYAN ANYWHERE, ANYTIME: COLLECTION ACCESSING LIBRARIES’ MATERIALS PG 8 FINDING PARALLELS PG 5 IN THE FADING INK elebrating anniversaries is such C PG 2 an important part of our culture because MEET they underscore the value we place on TERRY MOORE heritage and tradition. Anniversaries PG 14 speak to our impulse to acknowledge the things that endure. Few places CLUES FROM AN embody those acknowledgements more AMERICAN than a library—the keeper of things LETTER that endure. As the offi cial custodian of PG 11 the University’s history and the keeper of scholarly records, no other entity on LISTENING TO OUR campus is more immersed in the history STUDENTS of Ohio University than the Libraries. PG 16 OUR DONORS A LASTING LEGACY PG 20 This year marks the 200th anniversary of Ohio University Libraries. It was on PG 18 June 15, 1814 that the Board of Trustees fi rst named their collection of books the “Library of Ohio University,” codifi ed a Credits list of seven rules for its use, and later Dean of Libraries: appointed the fi rst librarian. Scott Seaman Editor: In the 200 years since its founding, Kate Mason, coordinator of communications and assistant to the dean Ohio University Libraries is now Co-Editor: Jen Doyle, graduate communications assistant ranked as one of the top 100 research Design: libraries in North America with print University Communications and Marketing collections of over 3 million volumes Photography: and, ranked by holdings, is the 65th Sherry Dibari, graduate photography assistant largest library in North America. -

GUARDIANS of AMERICAN LETTERS Roster As of February 2021

GUARDIANS OF AMERICAN LETTERS roster as of February 2021 An Anonymous Gift in honor of those who have been inspired by the impassioned writings of James Baldwin James Baldwin: Collected Essays In honor of Daniel Aaron Ralph Waldo Emerson: Collected Poems & Translations Charles Ackerman Richard Wright: Early Novels Arthur F. and Alice E. Adams Foundation Reporting World War II, Part II, in memory of Pfc. Paul Cauley Clark, U.S.M.C. The Civil War: The Third Year Told By Those Who Lived It, in memory of William B. Warren J. Aron Charitable Foundation Richard Henry Dana, Jr.: Two Years Before the Mast & Other Voyages, in memory of Jack Aron Reporting Vietnam: American Journalism 1959–1975, Parts I & II, in honor of the men and women who served in the War in Vietnam Vincent Astor Foundation, in honor of Brooke Astor Henry Adams: Novels: Mont Saint Michel, The Education Matthew Bacho H. P. Lovecraft: Tales Bay Foundation and Paul Foundation, in memory of Daniel A. Demarest Henry James: Novels 1881–1886 Frederick and Candace Beinecke Edgar Allan Poe: Poetry & Tales Edgar Allan Poe: Essays & Reviews Frank A. Bennack Jr. and Mary Lake Polan James Baldwin: Early Novels & Stories The Berkley Family Foundation American Speeches: Political Oratory from the Revolution to the Civil War American Speeches: Political Oratory from Abraham Lincoln to Bill Clinton The Civil War: The First Year Told By Those Who Lived It The Civil War: The Second Year Told By Those Who Lived It The Civil War: The Final Year Told By Those Who Lived It Ralph Waldo Emerson: Selected -

Remembering World War Ii in the Late 1990S

REMEMBERING WORLD WAR II IN THE LATE 1990S: A CASE OF PROSTHETIC MEMORY By JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Communication, Information, and Library Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Susan Keith and approved by Dr. Melissa Aronczyk ________________________________________ Dr. Jack Bratich _____________________________________________ Dr. Susan Keith ______________________________________________ Dr. Yael Zerubavel ___________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Remembering World War II in the Late 1990s: A Case of Prosthetic Memory JONATHAN MONROE BULLINGER Dissertation Director: Dr. Susan Keith This dissertation analyzes the late 1990s US remembrance of World War II utilizing Alison Landsberg’s (2004) concept of prosthetic memory. Building upon previous scholarship regarding World War II and memory (Beidler, 1998; Wood, 2006; Bodnar, 2010; Ramsay, 2015), this dissertation analyzes key works including Saving Private Ryan (1998), The Greatest Generation (1998), The Thin Red Line (1998), Medal of Honor (1999), Band of Brothers (2001), Call of Duty (2003), and The Pacific (2010) in order to better understand the version of World War II promulgated by Stephen E. Ambrose, Tom Brokaw, Steven Spielberg, and Tom Hanks. Arguing that this time period and its World War II representations -

2018–2019 Annual Report

2018–2019 Annual Report February 2020 Dear Library of America Supporter: Nicholas Lemann offers an annotated guide to key historical The past year was a remarkable one for texts that illuminate five urgent questions confronting our Library of America. As our 10 millionth democracy. Plus: exciting literary rediscoveries; further explo- series volume came off the press, LOA rations into the groundbreaking fiction of Shirley Jackson and was presented with the Los Angeles Times Ursula K. Le Guin; a literary valentine to our most popular Innovator’s Award for its unique role as pastime, bird watching; and an homage to the classic Amer- a champion of the democratic inclu- ican westerns of the 1940s and 50s. siveness of great American writing. Friends like you make all this possible, and we couldn’t do it While there is still much work ahead without you. We hope we can continue to make you proud to curating our vital and diverse tradition, be a Library of America supporter in the months and years the award is a gratifying recognition of ahead. how far we’ve come. Library of America’s pursuit of its mission is made With gratitude and warmest wishes for 2020, possible by the individuals and institutions who support it with contributions—among them the 1,549 donors on this 2020 Honor Roll who gave $100 or more in the past year. As the new year begins, we extend heartfelt thanks to our Max Rudin donors, members, and subscribers, and offer this glance President & Publisher ahead at a few of the highlights of the coming year: Free resources for teachers and general readers. -

The Cable Spring 2000

IUSS CAESAR The Cable Official Newsletter of the IUSS CAESAR Alumni Association Alumni Association Volume 4 Number 1 TURN-OF-THE CENTURY 2000 DIRECTOR’S CORNER Also, we try to ensure everyone is accounted for Ed Dalrymple in the People News section in at least one edition. If you have not been, it is strictly an oversight so please make me aware of it. We It is hard to believe we are entering into our sixth continue to have a number of members battling year! I’ve not heard from many of you since you significant illness themselves or in their families. first joined. Please feel free to update us on Please remember them in a manner of your yourself and anything else you care to. We have choosing. Until next time. EKD realized a slow and steady growth until we are now well over 300 members representing the myriad of specialties and talents that went into EVENTS of NOTE surveying, mapping, designing, producing, deploying and operating of the “System”. It 1999 appears our little Alumni Assn has become a focal point providing continuity between the past February and the present. I believe that we are the only CDR Larry D. Wilcher, USN received the Capt organization that has brought all the different and Joseph P. Kelly Award varied players of our community together: military (officer & enlisted), civilian (Govt & CDR Tonya Concannon, USN (ex-CO NOPF industry), sea operations/surveys, cable/array Whidbey Island) and installations, underwater/shore system design CDR Kim M. Drury, USN (ex-CUS N3) selected for engineers, cable production, ship ops, Captain, USN communications, fleet operators, intell April specialists, acquisition specialists, administrative and logisticians, Facilities management, CAPT Gerry Nifontoff, USN retirement ceremony acousticians, et al. -

Framework for Military Decision Making Under Risks

A Framework for Military Decision Making under Risks JAMES V. SCHULTZ, Lieutenant Colonel, USA School of Advanced Airpower Studies THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIRPOWER STUDIES, MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA, FOR COMPLETION OF GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS, ACADEMIC YEAR 1995–96. Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 1997 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii ABSTRACT . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ix 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 2 MILITARY DECISION MAKING AND PROSPECT THEORY . 5 3 MARKET GARDEN: CALCULATED RISK OR FOOLISH GAMBLE? . 19 4 APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK . 39 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 47 Illustrations Figure 1 Typical Value Function . 11 2 Weighting Function . 13 3 Relative Combat Power over Time . 35 Table 1 Estimate . 9 2 Prospect Theory and Estimate Process Matching . 14 iii Abstract This is a study of the applicability of prospect theory to military decision making. Prospect theory posits that the decision maker’s reference point determines the domain in which he makes a decision. If the domain is one of losses, the decision maker will tend to be risk seeking, if gains, then he will be risk averse. The author proposes that if prospect theory’s propositions are correct, then it may be possible for the decision maker, by assessing his own domain, to make better informed decisions. -

Ellery Queen 5 Misteri Per Ellery Queen Giallo Mondadori AA. VV. 55

AUTORE TITOLO GENERE EDITORE COLLANA ANNO EDIZIONE ISBN PREZZO NOTE 1977 Ellery Queen 5 misteri per Ellery Queen Giallo Mondadori Prima Edizione € 6,00 55/05 Cinquant'anni di 2006 professione la provincia di Fuori catalogo - AA. VV. Milano e i suoi architetti Electa 9788837040686 Dedica Harold Robbins 79,park avenue Sonzogno 1977 € 1,00 Tommaso Landolfi A caso 1975 Narrativa Club degli EditoriPremi Strega € 3,00 Jean d'Ormesson A Dio piacendo Rizzoli 1975 Prima Edizione € 4,00 Stephanie Kallos A pezzi per te Einaudi 2012 9788806192839 € 9,00 Peter Benchley Abissi Mondadori 1976 Prima Edizione € 1,00 Sheilah Graham- GeroldAdorabile Frank infedele mondadori 1961 prima ed. i pavone € 1,00 rovnato.segni a 1994 penna.puzza Oscar Wilde Aforismi Acquarelli 9788871224336 € 1,00 fumo Hans Herlin Album di Famiglia Sperling&Kupfer 1979 € 1,00 Alessandro I: lo zar della 2001 Henri Troyat Santa Alleanza Storia Bompiani Il Giornale-Biblioteca storica € 3,00 Wodehouse Alla buon ora jeeves! Bietti 1966 € 5,00 Manlio Cancogni Allegri, Gioventù Narrativa Rizzoli 1973 Terza Edizione € 1,00 Truman Capote Altre voci altre stanze Garzanti 1971 Prima Edizione € 10,00 E.M.Remarque Ama il prossimo tuo Classico Oscar Mondadori 1972 € 1,00 Scott Turow Ammissione di colpa Mondadori Oscar Mondadori 1993 € 3,00 Romantic 2008 Min Jin Lee Amori e pregiudizio o Einaudi Prima Edizione 9788806189891 € 10,00 Amori indimenticabili (3 Romantic 2018 Milly Johnson storie diverse) o Newton Compton € 5,00 Traver anatomia di un omicidio Garzanti 1970 Prima Edizione € 1,00 Antipasti caldi Euro Delices I grandi cuochi d'Europa vi invitano a tavola € 20,00 Banco Ambrosiano VenetoAntonello da Messina Arte Electa 1997 Prima Edizione € 12,00 E.M. -

Elenco Libri Completo Al 4-11-2017 in Ordine Di Anno E Titolo Titolo Autore Tipo Anno Cod

Elenco libri completo al 4-11-2017 in ordine di Anno e titolo Titolo Autore Tipo Anno Cod. Classificazione I racconti di Gramigna Don Vago Gabriele Libro 2017 6000 Narrativa Un caffè amaro per il commissario Dupin Jean Luc Bannalec Libro 2017 5699 Romanzo Duecentosei ossa Kathy Reichs Libro 2016 5700 Romanzo Il romanzo di mafia capitale Massimo Lugli Libro 2016 5701 Romanzo Il treno per Tallin Arno Saar Libro 2016 5707 Romanzo La civiltà perduta Elio Riviera Libro 2016 5537 Narrativa La costa Cremisi Douglas Preston Libro 2016 5702 Thriller La primavera tarda ad arrivare Flavio Santi Libro 2016 5701 Romanzo La ragazza di Brooklyn Guillaume Musso Libro 2016 5698 Thriller La ragazza del parco Alafair Burke Libro 2016 5699 Thriller La stanza delle torture Stuart Macbride Libro 2016 5700 Romanzo Thriller L'angelo Sandrone Dazieri Libro 2016 5706 Thriller Le solite sospette John Niven Libro 2016 5710 Romanzo Niceville Carsten Stroud Libro 2016 5711 Romanzo Thriller Urlare non basterà Brian McGilloway Libro 2016 5712 Romanzo Thriller Vicino al cadavere Stuart Macbride Libro 2016 5713 Romanzo Thriller Amore e altri imprevisti Maria Murnane Libro 2015 5731 Romanzo Binari divaganti Matteo Melotti Libro 2015 5518 Narrativa Central Park Guillaume Musso Libro 2015 5697 Thriller Come un ricordo che uccide Sabine Durrant Libro 2015 5478 Thriller Cuore depravato Patricia Cornwell Libro 2015 5694 Romanzo Homo dieteticus Marino Niola Libro 2015 5695 Diete I peccati della bocciofila Marco Ghizzoni Libro 2015 5511 Romanzo Il coraggio di ritornare liberi -

Ridgefield Encyclopedia

A compendium of more than 3,300 people, places and things relating to Ridgefield, Connecticut. by Jack Sanders [Note: Abbreviations and sources are explained at the end of the document. This work is being constantly expanded and revised; this version was updated on 4-14-2020.] A A&P: The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened a small grocery store at 378 Main Street in 1948 (long after liquor store — q.v.); became a supermarket at 46 Danbury Road in 1962 (now Walgreens site); closed November 1981. [JFS] A&P Liquor Store: Opened at 133½ Main Street Sept. 12, 1935. [P9/12/1935] Aaron’s Court: short, dead-end road serving 9 of 10 lots at 45 acre subdivision on the east side of Ridgebury Road by Lewis and Barry Finch, father-son, who had in 1980 proposed a corporate park here; named for Aaron Turner (q.v.), circus owner, who was born nearby. [RN] A Better Chance (ABC) is Ridgefield chapter of a national organization that sponsors talented, motivated children from inner-cities to attend RHS; students live at 32 Fairview Avenue; program began 1987. A Birdseye View: Column in Ridgefield Press for many years, written by Duncan Smith (q.v.) Abbe family: Lived on West Lane and West Mountain, 1935-36: James E. Abbe, noted photographer of celebrities, his wife, Polly Shorrock Abbe, and their three children Patience, Richard and John; the children became national celebrities when their 1936 book, “Around the World in Eleven Years.” written mostly by Patience, 11, became a bestseller. [WWW] Abbot, Dr. -

72 Winter Qtr 2010

The DAShPOT Issue 72 Newsletter of the Association of Minemen Winter 2010 37TH ANNUAL AOM REUNION POINT Loma, CA FROM THE PRESIDENT OCTOBER 14 - 16, 2011 Gary Cleland You are all welcome to attend the 37th Annual Greetings from sunny San Diego, California. I Association of Minemen Reunion and be part of am sure some of the membership may not have a most memorable event. We are putting togeth- heard of the happenings to our association since er the final touches for our reunion in San Diego, the conclusion of the reunion in Williamsburg, CA. I want to thank everyone for their assis- VA. I regret to inform those who have not heard tance, especially the 2011 Association of Mine- that our newly elected President Robert “Willie” men Committee, our President, our Directors, Wilson tragically died in a single car accident as well as all the involved members and friends, shortly after arriving home from the reunion. His for their assistance in our pulling together our wife Betty, although seriously injured, is on the reunion. We are looking forward to our 37th an- road to recovery. Keep Betty in our thoughts and nual reunion being held from 14 to 16 October in Prayers. You can see our website for additional San Diego at the Holiday Inn San Diego Bayside. details. This hotel location was selected by the AOM Re- As a result of Willie’s untimely passing, the fol- union Committee Team to house our reunion as lowing AOM leadership changes have occurred. well our annual meetings, functions and activities I, as your newly elected Vice President, have except for the picnic. -

Cornelius Ryan Collection of World War II Papers, Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University

Cornelius Ryan Collection of World War II Papers, Mahn Center for Archives and Special Collections, Ohio University A Bridge Too Far Inventory List First published by Simon & Schuster in 1974. A Bridge Too Far has been translated into Chinese, Czech, Dutch, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Malay, Persian, Polish, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, Slovenian, Spanish, Swedish, and Turkish. A movie version appeared in 1977, directed by Richard Attenborough and starring Dirk Bogarde, James Caan, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Edward Fox, Anthony Hopkins, Gene Hackman, Hardy Krüger, Laurence Olivier, Robert Redford, and Maximilian Schell. Alden Library has both VHS and DVD versions of the movie. Table of Contents Initial Research .........................................................................................................................................................................2 Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force ................................................................................................................. 7 American Forces ......................................................................................................................................................................8 British Forces .........................................................................................................................................................................45 Canadian Forces .....................................................................................................................................................................86