Is the Plan of Salvation Attested in the Dead Sea Scrolls?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sermons on the Old Testament of the Bible by Jesus of Nazareth

Sermons on the Old Testament of the Bible by Jesus of Nazareth THROUGH DR. DANIEL G. SAMUELS This online version published by Divine Truth, USA http://www.divinetruth.com/ version 1.0 Introduction to the Online Edition For those already familiar with the messages received through James Padgett , the Samuels channelings are a blessing in that they provide continuity and integration between the teachings of the Bible and the revelations received through Mr. Padgett. Samuels’ mediumship differed from Padgett’s in that it is much more filled with detail and subtlety, which makes it a perfect supplement to the “broad strokes” that Padgett’s mediumship painted with. However, with this greater resolution of detail comes greater risk of error, and it is true that we have found factual as well as conceptual errors in some of Samuel’s writings. There are also a number of passages where the wording is perhaps not as clear as we would have wished – where it appears that there was something of a “tug-of-war” going on between Samuels’ and Jesus’ mind. In upcoming editions we will attempt to notate these passages, but for now the reader is advised (as always) to read these messages with a prayerful heart, asking that their Celestial guides assist them in understanding the true intended meaning of these passages. The following is an excerpt from a message received from Jesus regarding the accuracy and clarity of Dr. Samuels’ mediumship: Received through KS 6-10-92 I am here now to write...and we are working with what is known as a "catch 22" on earth at this time, which means that it's very difficult to convince someone about the accuracy and clarity of a medium -through the use of mediumistic means. -

Too Small a Thing: Isaiah 49-66 Week 5

Too Small a Thing: Isaiah 49-66 week 5 Monday, April 7th--Isaiah 61:1-9 61 The Spirit of the Sovereign LORD is on me, because the LORD has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim freedom for the captives and release from darkness for the prisoners, 2 to proclaim the year of the LORD’s favor and the day of vengeance of our God, to comfort all who mourn, 3 and provide for those who grieve in Zion— to bestow on them a crown of beauty instead of ashes, the oil of joy instead of mourning, and a garment of praise instead of a spirit of despair. They will be called oaks of righteousness, a planting of the LORD for the display of his splendor. 4 They will rebuild the ancient ruins and restore the places long devastated; they will renew the ruined cities that have been devastated for generations. 5 Strangers will shepherd your flocks; foreigners will work your fields and vineyards. 6 And you will be called priests of the LORD, you will be named ministers of our God. You will feed on the wealth of nations, and in their riches you will boast. 1 Too Small a Thing: Isaiah 49-66 week 5 7 Instead of your shame you will receive a double portion, and instead of disgrace you will rejoice in your inheritance. And so you will inherit a double portion in your land, and everlasting joy will be yours. 8 “For I, the LORD, love justice; I hate robbery and wrongdoing. -

Calendar of Events

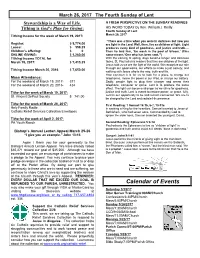

March 26, 2017 The Fourth Sunday of Lent \ Stewardship is a Way of Life. A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON THE SUNDAY READINGS Tithing is God’s Plan for Giving: HIS WORD TODAY by Rev. William J. Reilly Fourth Sunday of Lent Tithing Income for the week of March 19, 2017: March 26, 2017 “There was a time when you were in darkness but now you Regular: $ 5,774.00 are light in the Lord. Well, then, live as children of light. Light Loose: $ 359.25 produces every kind of goodness, and justice and truth…. Children’s offering: $ 0 Then he told him, ‘Go wash in the pool of Siloam.’ (This ONLINE GIVING: $ 1,280.00 name means ‘One who has been sent.’”) Tithing income TOTAL for With the coming of spring, days become longer and darkness March 19, 2017: $ 7,413.25 fades. St. Paul tells his readers that they are children of the light. Jesus told us we are the light of the world. We recognize our role Tithing Income March 20, 2016 $ 7,650.00 through our good works, our efforts to make a just society, and walking with Jesus who is the way, truth and life. How common it is for us to look for a place to charge our Mass Attendance: telephones, renew the power in our iPad, or charge our battery. For the weekend of March 19, 2017- 371 Sadly, people fight to plug their charger and renew their For the weekend of March 20, 2016- 424 telephone, computer or game. Lent is to produce the same effect. -

Mystery Babylon Exposed

Exposing Mystery Babylon An Attack On Lawlessness A Messianic Jewish Commentary Published At Smashwords By P.R. Otokletos Copyright 2013 P.R. Otokletos All Rights Reserved Table of Contents About the author Preface Introduction Hellenism a real matrix Hellenism in Religion The Grand Delusion The Christian Heritage Historical Deductions Part I Conclusion Part II Lawlessness Paul and Lawlessness Part II Conclusion Part III Defining Torah Part III Messiah and the Tree of Life Part IV Commandments Command 1 - I AM G_D Command 2 - No gods before The LORD Command 3 - Not to profane the Name of The LORD Command 4 - Observe the Sabbath Love The LORD Commands Summary Command 5 - Honor the father and the mother Command 6 - Not to murder Command 7 - Not to adulterate Command 8 - Not to steal Command 9 - Not to bear false testimony Command 10 - Not to covet Tree Of Life Summary Conclusion Final Thoughts About P. R. Otokletos The author Andrew A. Cullen has been writing under the pen name of P. R. Otokletos since 2004 when he began writing/blogging Messianic Jewish/Hebraic Roots commentaries across a broad range of topics. The author is part of an emerging movement of believing Jews as well as former Christians recapturing the Hebraic roots of the Messianic faith. A movement that openly receives not just the redemptive grace of the Gospel but also the transformational lifestyle that comes with joyful pursuit of G_D's Sacred Torah … just as it was in the first century Ce! Despite a successful career in politics and business, the author is driven first and foremost by a desire to understand the great G_D of creation and humanity's fate. -

The Book of Hebrews: Part 1 of 4 Lecture Video Transcription by Dr

The Book of Hebrews: Part 1 of 4 Lecture Video Transcription By Dr. D.A. Carson Research Professor of New Testament, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School In a book this long, transparently, we can’t go through every paragraph, every verse, so we're going to focus on certain crucial passages and to catch the flow of the argument through the book, the analytical outline will be a huge help. So what do we make of this book? Its readers, transparently, were an assembly, a congregation, or possibly more than one congregation, of Christians who at one time had been under persecution, but for whom the persecution had lightened up in more recent times. There is a considerable dispute in the commentaries as to whether these are Jewish Christians or gentile Christians. If they are Jewish Christians, they are Jewish Christians who are tempted to return to the social safety of their own Jewish communities, regaining the synagogue practices – or if they’re living anywhere near the temple, the temple practices – and so forth that were once at the heart of their religious life, but which in some measure they abandoned as Christians. Now they're tempted to return to them and the author sees this as a defection from the faith. Alternatively, if they are gentile Christians, they’re gentile Christians who are attracted beyond Christianity to a kind of Jewish form of Christianity taking on Jewish practices especially connected with the temple. In my view the former analysis squares with the facts a little better, but it won't make much difference to the overall argument of the book. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls: a Biography Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS: A BIOGRAPHY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John J. Collins | 288 pages | 08 Nov 2012 | Princeton University Press | 9780691143675 | English | New Jersey, United States The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Biography PDF Book It presents the story of the scrolls from several perspectives - from the people of Qumran, from those second temple Israelites living in Jerusalem, from the early Christians, and what it means today. The historian Josephus relates the division of the Jews of the Second Temple period into three orders: the Sadducees , the Pharisees , and the Essenes. Currently, he is completing a comprehensive, multi-volume study on the archaeology of Qumran. DSSEL covers only the non-biblical Qumran texts based on a formal understanding of what constitutes a biblical text. Enter email address. And he unravels the impassioned disputes surrounding the scrolls and Christianity. The scrolls include the oldest biblical manuscripts ever found. Also recovered were archeological artifacts that confirmed the scroll dates suggested by paleographic study. His heirs sponsored construction of the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem's Israel Museum, in which these unique manuscripts are exhibited to the public. In the first of the Dead Sea Scroll discoveries was made near the site of Qumran, at the northern end of the Dead Sea. For example, the species of animal from which the scrolls were fashioned — sheep or cow — was identified by comparing sections of the mitochondrial DNA found in the cells of the parchment skin to that of more than 10 species of animals until a match was found. Noam Mizrahi from the department of biblical studies, in collaboration with Prof. -

The Concept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate Faculty Publications and Presentations School 2010 The onceptC of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant Jintae Kim Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Jintae, "The oncC ept of Atonement in the Qumran Literature and the New Covenant" (2010). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 374. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lts_fac_pubs/374 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary and Graduate School at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [JGRChJ 7 (2010) 98-111] THE CONCEPT OF ATONEMENT IN THE QUMRAN LITERatURE AND THE NEW COVENANT Jintae Kim Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, Lynchburg, VA Since their first discovery in 1947, the Qumran Scrolls have drawn tremendous scholarly attention. One of the centers of the early discussion was whether one could find clues to the origin of Christianity in the Qumran literature.1 Among the areas of discussion were the possible connections between the Qumran literature and the New Testament con- cept of atonement.2 No overall consensus has yet been reached among scholars concerning this issue. -

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2000 The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints Donald W. Parry Stephen D. Ricks Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Parry, Donald W. and Ricks, Stephen D., "The eD ad Sea Scrolls: Questions and Responses for Latter-day Saints" (2000). Maxwell Institute Publications. 25. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface What is the Copper Scroll? Do the Dead Sea Scrolls contain lost books of the Bible? Did John the Baptist study with the people of Qumran? What is the Temple Scroll? What about DNA research and the scrolls? We have responded to scores of such questions on many occasions—while teaching graduate seminars and Hebrew courses at Brigham Young University, presenting papers at professional symposia, and speaking to various lay audiences. These settings are always positive experiences for us, particularly because they reveal that the general membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a deep interest in the scrolls and other writings from the ancient world. The nonbiblical Dead Sea Scrolls are of great import because they shed much light on the cultural, religious, and political position of some of the Jews who lived shortly before and during the time of Jesus Christ. -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

Joseph Smith's Interpretation of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon

SCRIPTURAL STUDIES Joseph Smith's Interpretation of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon David P. Wright THE BOOK OF MORMON (hereafter BM), which Joseph Smith published in 1830, is mainly an account of the descendants of an Israelite family who left Jerusalem around 600 B.C.E. to come to the New World. According to the book's story, this family not only kept a record of their history, which, added upon by their descendants, was to become the BM, but also brought with them to the Americas a copy of Isaiah's prophecies, from which the BM prophets cite Isaiah (1 Ne. 5:13; 19:22-23). Several chapters or sections of Isaiah are quoted in the BM: Isaiah 2-14 are cited in 2 Nephi 12-24; Isaiah 48-49 in 1 Nephi 20-21; Isaiah 49:22-52:2 in 2 Nephi 6:6-7,16- 8:25; Isaiah 52:7-10 in Mosiah 12:21-24; Isaiah 53 in Mosiah 14; and Isaiah 54 in 3 Nephi 22. Other shorter citations, paraphrases, and allusions are also found.1 The text of Isaiah in the BM for the most part follows the King James Version (hereafter KJV). There are some variants, but these are often in- significant or of minor note and therefore do not contribute greatly to clarifying the meaning of the text. The BM, however, does provide inter- pretation of or reflections on the meaning of Isaiah. This exegesis is usu- ally placed in chapters following citation of the text (compare 1 Ne. 22; 2 Ne. -

BSBB9401 DEAD SEA SCROLLS Fall 2018 Dr. R. Dennis Cole NOBTS Mcfarland Chair of Archaeology Dodd Faculty 201 [email protected] 504-282-4455 X3248

BSBB9401 DEAD SEA SCROLLS Fall 2018 Dr. R. Dennis Cole NOBTS Mcfarland Chair of Archaeology Dodd Faculty 201 [email protected] 504-282-4455 x3248 NOBTS MISSION STATEMENT The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. COURSE PURPOSE, CORE VALUE FOCUS, AND CURRICULUM COMPETENCIES New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary has five core values: Doctrinal Integrity, Spiritual Vitality, Mission Focus, Characteristic Excellence, and Servant Leadership. These values shape both the context and manner in which all curricula are taught, with “doctrinal integrity” and “characteristic academic excellence” being especially highlighted in this course. NOBTS has seven basic competencies guiding our degree programs. The student will develop skills in Biblical Exposition, Christian Theological Heritage, Disciple Making, Interpersonal Skills, Servant Leadership, Spiritual & Character Formation, and Worship Leadership. This course addresses primarily the compentency of “Biblical Exposition” competency by helping the student learn to interpret the Bible accurately through a better understanding of its historical and theological context. During the Academic Year 2018-19, the focal competency will be Doctrinal Integrity.. COURSE DESCRIPTION Research includes historical background and description of the Qumran cult and problems relating to the significance and dating of the Scrolls. Special emphasis is placed on a theological analysis of the non- biblical texts of the Dead Sea library on subjects such as God, man, and eschatology. Meaningful comparisons are sought in the Qumran view of sin, atonement, forgiveness, ethics, and messianic expectation with Jewish and Christian views of the Old and New Testaments as well as other Interbiblical literature. -

The Importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls for the Study of the Explicit Quotations in Ad Hebraeos

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls for the study of the explicit quotations inAd Hebraeos Author: The important contribution that the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) hold for New Testament studies is Gert J. Steyn¹ probably most evident in Ad Hebraeos. This contribution seeks to present an overview of Affiliation: relevant extant DSS fragments available for an investigation of the Old Testament explicit 1Department of New quotations and motifs in the book of Hebrews. A large number of the explicit quotations in Testament Studies, Faculty of Hebrews were already alluded to, or even quoted, in some of the DSS. The DSS are of great Theology, University of importance for the study of the explicit quotations in Ad Hebraeos in at least four areas, namely Pretoria, South Africa in terms of its text-critical value, the hermeneutical methods employed in both the DSS and Project leader: G.J. Steyn Hebrews, theological themes and motifs that surface in both works, and the socio-religious Project number: 02378450 background in which these quotations are embedded. After these four areas are briefly explored, this contribution concludes, among others, that one can cautiously imagine a similar Description Jewish sectarian matrix from which certain Christian converts might have come – such as the This research is part of the project, ‘Acts’, directed by author of Hebrews himself. Prof. Dr Gert Steyn, Department of New Testament Studies, Faculty of Theology, University of Introduction Pretoria. The relation between the text readings found among the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), those of the LXX witnesses and the quotations in Ad Hebraeos1 needs much more attention (Batdorf 1972:16–35; Corresponding author: 2 Gert Steyn, Bruce 1962/1963:217–232; Grässer 1964:171–176; Steyn 2003a:493–514; Wilcox 1988:647–656).