(Downloaded from Internet, Spring 2000) Compiled and Printed By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

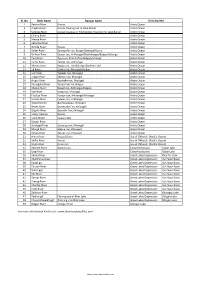

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Birding Tour Mongolia: Bird Specialties in Taiga and Gobi

BIRDING TOUR MONGOLIA: BIRD SPECIALTIES IN TAIGA AND GOBI 7 – 21 JUNE 2019 White-naped Crane is one of our target species on this tour. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Birding Tour Mongolia 2019 Welcome to our Birding Tour Mongolia, a birding and wildlife photography tour in some remote areas from the Siberian taiga through the high Altai Mountains to the Gobi Desert. Mongolia is one of the hottest birding sites in Asia. You can see a wide variety of birds in different natural habitats during this trip, driving in excellent company and with professional guides through splendid landscapes from Siberian taiga forest to the steppe in the country made famous by the Great Genghis Khan. Take this opportunity to make your dreams come true, seeing raptors such as Saker Falcon, Upland Buzzard, Amur Falcon, and Pallas’s Fish Eagle, but also Siberian Rubythroat, Black-billed Capercaillie, Henderson’s Ground Jay, and Altai Snowcock. Our targets in the different habitats are the following: In the Mongolian steppe Demoiselle Crane, Saker Falcon, Amur Falcon, Mongolian Lark, Oriental Plover, and Upland Buzzard, in the boreal forest of the taiga Siberian Rubythroat, Red-flanked Bluetail, Pine Bunting, Black billed Capercaillie, and Chinese Bush Warbler, in the wetlands White-naped Crane, Asian Dowitcher, Swan Goose, and migratory stints, and in the Gobi Desert Altai Snowcock, Kozlov's Accentor, Henderson’s Ground Jay, and Asian Desert Warbler. In addition we might also see Gray Wolf, Mongolian Gazelle, Siberian Ibex, and Argali (mountain sheep). Expect more than 200 species for the trip, depending on the season. -

Assemblée Nationale Constitution Du 4 Octobre 1958 Quatorzième Législature

ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE CONSTITUTION DU 4 OCTOBRE 1958 QUATORZIÈME LÉGISLATURE _____________________________________________________ R A P P O R T D’ I N F O R M A T I O N Présenté à la suite de la mission effectuée en République de Mongolie du 8 au 12 juillet 2014 par une délégation du (1) GROUPE D’AMITIÉ FRANCE-MONGOLIE ____________________________________________________ (1) Cette délégation était composée de M. Jérôme Chartier, Président, Mmes Catherine Quéré et Françoise Dumas, et M. Francis Hillmeyer. – 3 – SOMMAIRE CARTE DE LA MONGOLIE ........................................................ 5 PREFACE ........................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 9 I. Une jeune démocratie ........................................................... 15 A. DU FÉODALISME AU MULTIPARTISME ...................................... 15 1. L’héritage du passé ...................................................................... 15 2. La transition démocratique .......................................................... 16 B. L’ANCRAGE DÉMOCRATIQUE ................................................... 18 1. L’équilibre des pouvoirs .............................................................. 18 2. La culture de l’alternance ............................................................ 20 3. La classe politique mongole : deux portraits ............................... 24 C. L’OUVERTURE INTERNATIONALE ........................................... -

Part I Master Plan

PART I MASTER PLAN CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION I MASTER PLAN PART I MASTER PLAN CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study In Mongolia some 50% of the total population of about 2.4 million are nomadic families. For the nomadic families Sum centers are key places for supplying their vital goods, and also for receiving public services such as administration, medical care, education, etc. As of November 1997, the electric power at 117 out of 314 Sum centers in total in Mongolia is being supplied from the national power transmission network. At the remaining 197 Sum centers, the electric power is supplied by the diesel engine generators by Sum center independently. Most of these diesels generating facilities were manufactured during the former Soviet Union era and installed long ago from 1963 to 1990. During the Social Republic era of the country, Mongolia depended on the Soviet Union for the supply of spare parts necessary for maintenance of the generating equipment and technical guidance. Due to the corruption of the Soviet Union's economy in 1991 and associated transition to a market economy, the following four factors caused troubles to the operation and maintenance of the Sum's generating facilities, i.e. (1) the lack of business operating senses, (2) the interruption of spare parts supply, (3) the lack of technical capability and (4) shortage of management budget. The operation of much equipment has been obliged to be kept stopped after failure, as operators cannot repair them. The affected generation quantity, and aggravated the conditions of daily lives of people in Sum center and caused serious effects to the socio-economic activities of the Sum centers. -

Asian Literature and Translation Yeke Caaji, the Mongol-Oyirod Great

Asian Literature and Translation ISSN 2051-5863 https://doi.org/10.18573/alt.38 Vol 5, No. 1, 2018, 267-330 Yeke Caaji, the Mongol-Oyirod Great Code of 1640: Innovation in Eurasian State Formation Richard Taupier Date Accepted: 1/3/2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC-BY-NC-ND) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ©Richard Taupier Asian Literature and Translation Vol. 5 No. 1 2018 267-330 Yeke Caaji: The Mongol-Oyirod Great Code of 1640: Innovation in Eurasian State Formation Richard Taupier Introduction In the year 1640 an assembly (kuriltai) of Mongol and Oyirod1 nobles gathered to discuss and approve a code of law intended to govern relationships among them and to regulate the behavior of their subjects. While the resulting document is reasonably well known among scholars of Central Asia, it is the position of this work that its purpose has been largely misunderstood and that modern descriptions of early seventeenth century Oyirod history are confused and incomplete. This current work endeavors to establish a better understanding of the motivations behind the Great Code of 1640 and what the participants hoped to gain by its adoption. It does so through a close examination of the text itself and other original Oyirod sources and an analysis of competing secondary narratives. This creates the opportunity to reconsider the document from new and more carefully articulated perspectives. The result is an appreciation of the Great Code as an important document in Mongolian history. Through this perspective we can see the document as a sign of waning Chinggisid authority and recognition that innovation in state formation was needed to enable the continued existence of the Mongol and Oyirod states. -

Nomadic Party GER to GER

Nine Dragon Heads 19th. Aug ~ 9th. Sept. 2013 Nomadic Party GER to GER Organization Boards Annelise Zwez Bruce Allan Denizhan Ozer Gabriel Adams Jessy Rahman Nandin Erdene. B Park Byoung-Uk Paul Donker Duyvis Susanne Muller Staff Goo So-Young Jeong Ji-Yoon Song-Wha 1 Nine Dragon Heads aspires to generate positive environmental and spiritual legacies for the future. This is in a context where humankind benefits from manipulating and dominating its natural surroundings; regarding the natural environment as a target and challenge for conquest, a test of its ability to transform and possess nature. Our desire and ingenuity to exploit and develop the natural environment through domination and control implies superiority. Reflecting on the history of the planet however, many species of all forms became extinct when the friendly environmental conditions that firstly nurtured their birth later changed and became hostile. The question of when will humankind disappear hangs over us. No matter how 'special' we Homo Sapiens think we may be, we have to realise we are a part of the greater natural world and the product of a unique environment that supports our life. How can we lead a life with understanding and respect for the world of nature? How can we maintain a life peacefully and fairly for the survival of mankind? Nine Dragon Heads changes ‘I’ into ‘we’, a community of artists, who explore and re-consider the relationship and equilibrium between people and the natural environment. Nine Dragon Heads joins with other communities to share their imagination, experience and ideas through creative art practices, to reveal and celebrate both diverse and common consciousness and to further co- operation. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

I HISTORICAL PROLOGUE The Land and the People Demchugdongrob, commonly known as De Wang (Prince De in Chinese), was a thirty-first generation descendant of Chinggis Khan and the last ruler of Mongolia from the altan urag, the Golden Clan of the Chinggisids. The only son of Prince Namjilwang- chug, Demchugdongrob was bom in the Sunid Right Banner of Inner Mongolia in 1902 and died in Hohhot, the capital of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, in 1966. The Sunid was one of the tribes that initially supported Chinggis Khan (r. 1206- 1227). In the sixteenth century, Dayan Khan reunified Mongolia and put this tribe under the control of his eldest son, Torubolod. Thereafter, the descendants of Torubolod be came the rulers not only of the Sunid but also of the Chahar (Chakhar), Ujumuchin, and Khauchid tribes. The Chahar tribe was always under the direct control of the khan him self During the Manchu domination, the Sunid was divided into the Right Flank and Left Flank Banners, and both were part of the group of banners placed under the Shilingol League. During the first half of the seventeenth century, the Manchus expanded to the southern parts of Manchuria and began to compete with the Ming Chinese. Realizing the danger in the rise of the Manchus, Ligdan Khan, the last Mongolian Grand Khan, aban doned his people ’s traditional hostility toward the Chinese and formed an alliance with the Ming court to fight the Manchus. Although this policy was prudent, it was unaccept able to most Mongolian tribal leaders, who subsequently rebelled and joined the Manchu camp. -

The Rise of Steppe Agriculture

The Rise of Steppe Agriculture The Social and Natural Environment Changes in Hetao (1840s-1940s) Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Yifu Wang aus Taiyuan, V. R. China WS 2017/18 Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Sabine Dabringhaus Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Dr. Franz-Josef Brüggemeier Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen und der Philosophischen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Joachim Grage Datum der Disputation: 01. 08. 2018 Table of Contents List of Figures 5 Acknowledgments 1 1. Prologue 3 1.1 Hetao and its modern environmental crisis 3 1.1.1 Geographical and historical context 4 1.1.2 Natural characteristics 6 1.1.3 Beacons of nature: Recent natural disasters in Hetao 11 1.2 Aims and current state of research 18 1.3 Sources and secondary materials 27 2. From Mongol to Manchu: the initial development of steppe agriculture (1300s-1700s) 32 2.1 The Mongolian steppe during the post-Mongol empire era (1300s-1500s) 33 2.1.1 Tuntian and steppe cities in the fourteenth century 33 2.1.2 The political impact on the steppe environment during the North-South confrontation 41 2.2 Manchu-Mongolia relations in the early seventeenth century 48 2.2.1 From a military alliance to an unequal relationship 48 2.2.2 A new management system for Mongolia 51 2.2.3 Divide in order to rule: religion and the Mongolian Policy 59 2.3 The natural environmental impact of the Qing Dynasty's Mongolian policy 65 2.3.1 Agricultural production 67 2.3.2 Wild animals 68 2.3.3 Wild plants of economic value 70 1 2.3.4 Mining 72 2.4 Summary 74 3. -

Relict Topography Within the Hangay Mountains in Central Mongolia: 2 Quantifying Long-Term Exhumation and Relief Change in an Old Landscape 3 4 Kalin T

1 Relict topography within the Hangay Mountains in central Mongolia: 2 Quantifying long-term exhumation and relief change in an old landscape 3 4 Kalin T. McDannella,b*, Peter K. Zeitlera, and Bruce D. Idlemana 5 6 aDepartment of Earth & Environmental Sciences, Lehigh University, 1 W Packer Ave., Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA 7 8 bNatural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada, 3303 33 St NW, Calgary, AB T2L 2A7 9 10 Corresponding author: [email protected] 11 12 Key Points 13 ° New bedrock and detrital apatite (U-Th)/He cooling ages were determined for the Hangay 14 Mountains and central Mongolia 15 ° Thermo-kinematic modeling suggests relief change in the Mesozoic with slow exhumation 16 rates on the order of <20 m/My since the Cretaceous 17 ° Coupled Pecube-Neighborhood Algorithm modeling is successfully applied in a slowly 18 eroding setting 19 20 Abstract 21 The Hangay Mountains are a high-elevation, low-relief landscape within the greater Mongolian 22 Plateau of central Asia. New bedrock apatite (U-Th)/He single-grain ages from the Hangay span 23 ~70 to 200 Ma, with a mean of 122.7 ± 24.0 Ma (2σ). Detrital apatite samples from the Selenga 24 and Orkhon Rivers, north of the mountains, yield dominant (U-Th)/He age populations of ~115 25 to 130 Ma, as well as an older population not seen in the Hangay granitic bedrock data. These 26 low-temperature data record regional exhumation of central Mongolia in the Mesozoic followed 27 by limited erosion of <1-2 km since the Cretaceous, ruling out rapid exhumation of this 28 magnitude associated with any late Cenozoic uplift. -

Mongolia: Issues for Congress

Mongolia: Issues for Congress Susan V. Lawrence Specialist in Asian Affairs September 3, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41867 Mongolia: Issues for Congress Summary Mongolia is a sparsely populated young democracy in a remote part of Asia, sandwiched between two powerful large neighbors, China and Russia. It made its transition to democracy and free market reforms peacefully in 1990, after nearly 70 years as a Soviet satellite state. A quarter of a century later, the predominantly Tibetan Buddhist nation remains the only formerly Communist Asian nation to have embraced democracy. Congress has shown a strong interest in Mongolia since 1990, funding assistance programs, approving the transfer of excess defense articles, ratifying a bilateral investment treaty, passing legislation to extend permanent normal trade relations, and passing seven resolutions commending Mongolia’s progress and supporting strong U.S.-Mongolia relations. Congressional interest is Mongolia has focused on the country’s story of democratic development. Since passing a democratic constitution in 1992, Mongolia has held six direct presidential elections and six direct parliamentary elections. The State Department considers Mongolia’s most recent elections to have been generally “free and fair” and said that in 2013, Mongolia “generally respected” freedoms of speech, press, assembly, and association. It raised concerns, however, about corruption and lack of transparency in government affairs. On the economic front, Mongolia’s mineral wealth, including significant reserves of coal, copper, gold, and uranium, offers investment opportunities for American companies. Foreign investors and the U.S. government have criticized Mongolia’s unpredictable investment climate, however. In the fall of 2013, Mongolia passed a new investment law and, after years of negotiations, signed a transparency agreement with the United States. -

Analysis of the Shamanic Empire of the Early Qing, Its Role in Inner Asian

THE SHAMANIC EMPIRE AND THE HEAVENLY ASTUTE KHAN: ANALYSIS OF THE SHAMANIC EMPIRE OF THE EARLY QING, ITS ROLE IN INNER ASIAN HEGEMONY, THE NATURE OF SHAMANIC KHANSHIP, AND IMPLICATIONS FOR MANCHU IDENTITY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY May 2020 By Stephen Garrett Thesis Committee: Shana Brown, Chairperson Edward Davis Wensheng Wang Keywords: Qing Dynasty, Manchu, Mongol, Inner Asia, Shamanism, Religion and Empire Acknowledgments: I would like to first and foremost show my deepest gratitude to my master’s thesis advisor, Dr. Shana Brown, whose ongoing uplifting support and instrumental advice were central to my academic success, without which I couldn’t have reached the finish line. I would also like to extend deepest thanks to my master’s thesis committee members Dr. Edward Davis and Dr. Wensheng Wang, who freely offered their time, efforts, and expertise to support me during this thesis project. Additionally, I would like to extend thanks to Dr. Mathew Lauzon and Dr. Matthew Romaniello, who both offered a great deal of academic and career advice, for which I am greatly appreciative. Special thanks to my peers: Ryan Fleming, Reed Riggs, Sun Yunhe, Wong Wengpok, and the many other friends and colleagues I have made during my time at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. They have always been a wellspring of academic advice, discussion, and support. While writing my master’s thesis, I have had the pleasure of working with the wonderful professional staff and faculty of the University of Hawaii at Manoa, whose instruction and support were invaluable to my academic success. -

Modern Inner Mongolia (Central Eurasian Studies 569) Syllabus for the Course Offered in Spring 2001 Indiana University Dept

«Central Asian Studies World Wide» Course Syllabi for the Study of Central Eurasia www.fas.harvard.edu/~casww/CASWW_Syllabi.html Prof. Christopher P. Atwood Modern Inner Mongolia (Central Eurasian Studies 569) Syllabus for the course offered in Spring 2001 Indiana University Dept. of Central Eurasian Studies Prof. Christopher P. Atwood Department of Central Eurasian Studies Indiana University Goodbody Hall 321 1011 East 3rd St. Bloomington, IN 47405-7005 U.S.A. [email protected] CASWW - Syllabi Christopher P. Atwood, Modern Inner Mongolia U569 Modern Inner Mongolia (0719) Syllabus Spring, 2001 Instructor: Professor Christopher P. Atwood Phone: 855-4059; email: catwood Time: Days and Time: Tuesday and Thursday, 1:00-2:15. Place: Ballantine Hall 316 Office Hours: 11:15-12:05 T, 1:00-1:50 W and by arrangement Office: Goodbody Hall 321 Description: What region in the world has the largest population of ethnic Mongols? What region in Chinese was the first testing ground for the Chinese Communist minority policy? What region in China has had the most lasting impact from the Japanese occupation during World War II? What region of the world produces the largest part of the world’s cashmere and most of its rare earths? Which region in China suffered the most in the Cultural Revolution? The answer to all these questions is: Inner Mongolia. This course explores the fascinating and often tragic history of Inner Mongolia from about 1800 to the present. We will trace the patterns of Mongolian institutions and ideas and Han Chinese immigration and settlement through the Qing, the New Policies, the Chinese Republic, the Japanese Occupation, the Chinese Civil War, and the see-sawing PRC policies.