November 2000 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brass Chamber Ensembles David Scott, Director Abstract No

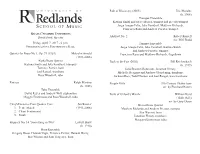

Path of Discovery (2005) Eric Morales (b. 1966) Trumpet Ensemble Katrina Smith and Steve Morics, trumpet and piccolo trumpet Jorge Araujo-Felix, Jake Ferntheil, Matthew Richards, Francisco Razo and Andrew Priester, trumpet Brass Chamber Ensembles David Scott, director Abstract No. 2 Robert Russell Arr. Wiff Rudd Friday, April 7, 2017 - 6 p.m. Trumpet Ensemble Frederick Loewe Performance Hall Jorge Araujo-Felix, Jake Ferntheil, Katrina Smith and Andrew Priester, trumpet Quintet for Brass No.1, Op. 73 (1961) Malcolm Arnold Francisco Razo and Matthew Richards, flugelhorn (1921-2006) Alpha Brass Quintet Back to the Fair (2002) Bill Reichenbach Katrina Smith and Jake Ferntheil, trumpets (b. 1949) Terrence Perrier, horn Julia Broome-Robinson, Jonathan Heruty, Joel Rangel, trombone Michelle Reygoza and Andrew Glendening, trombone Ross Woodzell, tuba Jackson Rice, Todd Thorsen and Joel Rangel, bass trombone Fantasy Ralph Martino Simple Gifts 19th Century Shaker tune (b. 1945) arr. by Eberhard Ramm Tuba Ensemble David Reyes and Andrew Will, euphonium Earle of Oxford’s Marche William Byrd Maggie Eronimous and Ross Woodzell, tuba (1540-1623) arr. by Gary Olson Cinq Miniatures Pour Quatres Cors Jan Kotsier Bravo Brass Quintet 1. Petite March (1911-2006) Matthew Richards and Andrew Priester, trumpet 2. Chant Sentimental Star Wasson, horn 5. Finale Jonathan Heruty, trombone Margaret Eronimous, tuba Frippery No. 14 “Something in Two” Lowell Shaw (b. 1930) Horn Ensemble Gregory Reust, Hannah Vagts, Terrence Perrier, Hannah Henry, Star Wasson and Sam Tragesser, horn Fanfares Liturgiques Henri Tomasi from his London Philharmonic Orchestra days is revealed by his expert i. Annonciation (1901-1971) use of the contrast of tone color and timbre of the brass family in different ii. -

Solo and Ensemble Recognized Events

RECOGNIZED SOLO AND ENSEMBLE EVENTS (The event number is to be used on the Solo and Ensemble entry form.) WOODWIND SOLO BRASS SOLO PERCUSSION SOLO PIANO SOLO 1. Piccolo 050. Cornet/Trumpet +099. Drum Set 150. Piano Solo 2. C Flute 051. Flugelhorn +100. Xylophone/Marimba/Vibraphone 3. Alto/Bass Flute 052. French Horn +101. Orch. bells 4. Oboe 053. Mellophone/Alto Horn (Group IV & V only) 5. English Horn 054. Trombone +102. Snare Drum VOCAL SOLO 6. Bassoon/Contrabassoon 055. Bass Trombone +103. Tympani 160. Vocal Solo 7. Eb Clarinet 056. Baritone/Euphonium (accompanied or unaccomp.) VOCAL ENSEMBLE 8. Bb Clarinet 057. Tuba/Sousaphone 104. Multiple Percussion 170. Barbershop Quartet 9. Alto Clarinet +105. Multi-Tenor (a cappella) 10. Bass Clarinet BRASS TRIO 175. Small Vocal Ensemble 11. Contra Bass/ 065. Cornet/Trumpet Trio + Refer to Percussion Manual (3 to 6 performers) Contra Alto Clarinet 066. French Horn Trio for additional requirements *180. Large Vocal Ensemble 12. Alto Sax 067. Trombone Trio PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE (7 to 20 performers) 13. Tenor Sax 068. Brass Trio (Tpt., Horn, 110. Percussion Ensemble *185. Madrigal 14. Baritone Sax Trombone) (3-6 performers) (4 to 20 performers) 15. Bass Sax 069. Misc. Brass Trio 111. Mallet Ensemble (a cappella) 16. Soprano Sax (Bb & Eb) (any combination of 3 brasses (3-6 performers) not previously listed) WOODWIND TRIO *112. Large Mallet Ensemble 025. Flute Trio. Like Inst. BRASS QUARTET (7-20 performers) 026. Clarinet Trio. Like Inst. 070. Cornet/Trumpet Quartet *113. Large Percussion Ens. 027. Sax Trio. Any 3 Sax 071. French Horn Quartet (7-20 percussion inst. -

Coaching the Brass Quintet: Developing Better Student Musicians Through Chamber Music

COACHING THE BRASS QUINTET: DEVELOPING BETTER STUDENT MUSICIANS THROUGH CHAMBER MUSIC By Albert E. Miller Jr. Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Davidson ________________________________ Professor Scott Watson ________________________________ Dr. Alan Street ________________________________ Dr. Paul Popiel ________________________________ Dr. Martin Bergee Date Defended: April 1st, 2014 ! ii" The Dissertation Committee for Albert E. Miller Jr. certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: COACHING THE BRASS QUINTET: DEVELOPING BETTER STUDENT MUSICIANS THROUGH CHAMBER MUSIC ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Davidson Date approved: April 15, 2014 " iii Abstract The brass quintet is currently one of the most predominant outlets for brass players to gain vital chamber music experience in the university setting. As a result, the role of applied brass instructors at universities has evolved into a role that is not entirely different than that of a conductor. The applied instructor plays the role of chamber coach, often without the skills necessary to provide the students with the skills they need for chamber music playing. This document seeks to provide the novice brass chamber coach with a guide as to the role of the applied professor in the musical and extra-musical development of young players. It will provide vital information for the coach that includes rehearsal strategies as well as samples of common performance issues found in the repertoire. While the amount of different rehearsal strategies and concepts is vast, this document aims to give the novice coach a primer for the instruction of student chamber ensembles. -

Kansas Brass Quintet

Kansas Brass Quintet Members STEVE LEISRING joined the KU faculty as Assistant Professor of Trumpet and Principal Trumpet of the Kansas Brass Quintet in the fall of 2004 after fourteen seasons as a member of the Tenerife Symphony Orchestra, Canary Islands, Spain. As a member of the orchestra, he made more than 25 orchestral recordings, and regularly performed with world-class artists throughout Spain and other European countries. Other experience include performing as Principal Trumpet and soloist with the Tenerife Chamber Orchestra, as well as performances with Neemi Jarvi and the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra from Sweden, the Dallas Symphony, and the Music in the Mountains Festival Orchestra in Durango, CO. An active teacher while in Spain, former students from the island of Tenerife have gone on to perform with the New York Philharmonic, Pacific Music Festival in Japan, as well as in music festivals in France, Finland and Spain NITAI PONS-TRUMPET A native of Yauco, Puerto Rico, Nitai is currently pursuing a Doctoral degree in trumpet performance with Professor Stephen Leisring, as well as serving as a Teaching Assistant. He has a Masters from KU in 2007, and received his Bachelors in Music Education from the Puerto Rick Music Conservatory in 2001. Nitai has a great deal of performing experience, having played with ensembles such as the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra, the Lawrence Chamber Orchestra, the Fountain City Brass Band, the Caribbean Brass Quintet, Principal Trumpet of both the University of Kansas Symphony Orchestra and the University of Kansas Wind Ensemble, the Idyllwild Festival Orchestra, and the Festival of the Youth Symphony Orchestra of the Americas (FOSJA), Puerto Rico. -

Brass Quintet Literature of Thom Ritter George

A GUIDE FOR THE PREPARATION, ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE OF THE BRASS QUINTET LITERATURE OF THOM RITTER GEORGE, WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY BACH, BITSCH, HANDEL, TORELLI, SUDERBERG, KETTING AND OTHERS William J. Stowman, B.S., M.A., M.M.E. APPROVED: Major Professop Minor Pro s or Committee Member Dean of the Co ege of Music Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies A GUIDE FOR THE PREPARATION, ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE OF THE BRASS QUINTET LITERATURE OF THOM RITTER GEORGE, WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY BACH, BITSCH, HANDEL, TORELLI, SUDERBERG, KETTING AND OTHERS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By William J. Stowman, B.S., M.A., MME. Denton, Texas May, 1998 Stowman, William J. A Guide for the Preparation. Analysis. and Performance of the Brass Quintet Literature of Thom Ritter George. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May, 1998, 72 pp., 52 bibliography. An examination of the musical style, compositional techniques and performance practice issues of American Composer Thom Ritter George with special attention paid to his Quintet No. 4 written in 1986. The document also includes a short history of brass instruments in chamber music, history of the brass quintet in America, discussion of the role of the trumpet in the quintet, overview of the composers contributions to music and brass quintet, and background information on the composer. A detailed analysis of Quintet No. 4 is provided. Issues of performance practice are discussed through theoretical analysis and in interviews with the composer. -

Americanbrass Quintet

merican rass uintet A FORTFORTY-SIXTHY-SIXTHB SEASONS EASONQ Volume 15, Number 1 New York, November 2006 ew sletter It's All in the Timing— N New Works in the Works By Raymond Mase Rojak on the Road - 2006 By John Rojak As we prepared for our 45th Once again, the ABQ hit the road for another season anniversary last season, I was of touring. This being the quintet's 45th anniversary, there was relieved to see that things an air of great events anticipated, as well as some excitement were falling into place so about our new repertoire and recordings. Our fall season was that our year would include book-ended by engagements within a few hours drive from merican several major new works. home. It's nice to have some of the stress removed from trav - A Sometimes the timing of el–avoiding check-in, security, luggage that may or may not Brass Quintet new pieces can't be com - arrive at the same airport as us, and who knows what else. In FORTY-SIXTH SEASON pletely predicted, but thank - between those venues, which were Wesleyan College in fully our 45th anniversary year Middletown, Connecticut, and Gretna Concerts in 1960-2006 worked out perfectly. One stroke Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, we traveled to Minnesota, and of luck was that our 45th just hap - spent a week in uptown New York City, recording our brass pened to coincide with the Juilliard Centennial, and as part of band cd, which you will read about elsewhere in this newslet - that celebration, Juilliard had commissioned Joan Tower to ter. -

A Curriculum for Tuba Performance in a Commercial Brass

A CURRICULUM FOR TUBA PERFORMANCE IN A COMMERCIAL BRASS QUINTET BY PAUL CARLSON Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Daniel Perantoni __________________________________ Kyle Adams __________________________________ Jeffrey Nelsen __________________________________ John Rommel ii Preface While a curriculum for any type of performance could be synthesized by theoretical reasoning based upon knowledge of how to learn any new genre or style of music, it is tradition that students turn to leaders in the field to gain insight and knowledge into the specific craft that they wish to pursue. While pure scholarship and study of a repertoire is an excellent way to gain insight into a performance arena, time spent in the field actually performing a certain style of music as a member of a professional ensemble gives a perspective that is intrinsically valuable to a project such as this. In addition to the sources listed in the bibliography and the extensive research done concerning this project, I have been a member of the Dallas Brass Quintet since September of 2010. I currently continue to serve as their tubist. Being a member of this ensemble, which is one of the most active touring commercial styled brass quintets in existence today, has greatly informed me concerning this project in terms of the demands of this type of performance. As I prepared to write this document, I took inventory of the skills and preparation that have allowed me to perform successfully in a commercial brass quintet. -

University of Georgia British Brass Band Philip Smith, Bandmaster Tuesday, October 10, 2017 • 8:00 P.M

UGA British Brass Band University of Georgia British Brass Band Philip Smith, Bandmaster Tuesday, October 10, 2017 • 8:00 p.m. “Songs of a People” PROGRAM FEATURING Dorothy Gates.............................................Fanfare – All Glorious Leslie Condon........................................The Call of the Righteous Bruce Broughton........................................Songs from the States Traditional/Arr. by William Himes..........................Amazing Grace Leroy Anderson/Arr. by Mark Freeh......................Belle of the Ball Leroy Anderson/Arr. by Mark Freeh.........March of theTwo Left Fee Ernesto Lecuona/Arr. by Mark Freeh...........................Malaguena The UGA British Brass Band Philip Smith The UGA British Brass Band was estab- Philip Smith joined the Hugh Hodgson UGA British Brass Band lished in August, 2014, coinciding with the School of Music as the William F. and Pa- appointment of Philip Smith as Prokasy mela P. Prokasy Professor in the Arts in bandmaster Philip Smith Professor in the Arts to the trumpet fac- August, 2014. In addition to teaching his ulty of the Hugh Hodgson School of Mu- trumpet studio, he is the Bandmaster of the SOPRANO CORNET SOLO HORN BASS TROMBONE sic. The band features the instrumentation UGA British Brass Band, member of the Yanbin Chen Andrew Sehman Kyle Moore Dilon Bryan that is standard for brass bands around the faculty Georgia Brass Quintet, and coach of PRINCIPAL CORNET SOLO EUPHONIUM world. Members are chosen through audi- the Bulldog Brass Society. This new position Shaun Branam FIRST HORN Timothy Morris tions each semester. In its short history, follows his retirement from the New York Duncan Robertson Eric Dluzniewski SOLO CORNET the UGA British Brass Band has quickly Philharmonic after 36 years of service as Deborah Caldwell SECOND HORN EUPHONIUM become a favorite of audiences of all ages. -

Clayton Thomas Garrett • Tuba

CLAYTON THOMAS GARRETT TUBA 4901 MEADOW WOOD DR WACO, TEXAS 76710 [email protected] 903.521.8424 EDUCATION ABD University of Texas at Austin, Doctor of Musical Arts, Tuba Performance 2010-2012 University of North Texas, Doctoral Studies, Tuba Performance 2010 Baylor University, Master of Music, Tuba Performance 2008 University of Texas at Tyler, Bachelor of Music, Tuba Performance PRINCIPAL TEACHERS Charles Villarrubia, University of Texas at Austin Danny Vinson, University of Texas at Tyler Don Little, University of North Texas Mark Wolfe, University of Texas at Tyler Kent Eshelman, Baylor University Heather Mensch, Tyler Junior College David Graves, Baylor University TEACHING EXPERIENCE – COLLEGIATE Current Texas A&M University – Kingsville Adjunct Instructor • Teach overload tuba and euphonium music majors Current Temple College – Temple, TX Adjunct Instructor • Manage a studio of tuba and euphonium music majors • Interim music theory instructor 2018 – Current McLennan Community College – Waco, TX 2013 – 2014 Adjunct Instructor • Manage undergraduate tuba studio • Listened to and graded all brass and woodwind juries 2014-2016 University of Texas at Austin – Austin, TX Graduate Teaching Assistant • Manage a studio of 4-7 non-major and secondary instrument students taking weekly private lessons • Guide students’ progress on etudes, technique and solo repertoire • Listen to and grade end-of-semester juries • Support Butler School of Music faculty with scheduling, supplementary teaching, liasing with guest artists. • Lead -

Works by Martin Bresnick, Mel Powell, Ronald Roseman, Ralph Shapey

Works by Martin Bresnick, Mel Powell, Ronald Roseman, Ralph Shapey New World 80413-2 The woodwind quintet is to the wind instruments as the string quartet is to the strings. Composers have treated the heterogenous ensemble of flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn as a unity for so long now that it has become a musical commonplace. The challenge in composing for the woodwind quintet is to weave a consistent musical fabric while respecting the disparate characters of the five instruments. The four composers represented on this recording meet this challenge with imagination and mastery. Ronald Roseman (born 1933 in Brooklyn, New York) is well known as an oboist, with over fifty-five solo and chamber recordings to his credit. He is also a composer whose teachers were Henry Cowell, Ben Weber, Karol Rathaus, and Elliott Carter. He is currently a professor at Yale, Queens College, and The Juilliard School. Roseman's Double Quintet for woodwind and brass was written in 1987 on commission from Yale's Norfolk Chamber Music Festival and is dedicated to Joan Panetti, the director of the festival. The Double Quintet opens with a moody slow introduction followed by an Allegro energico, reminiscent of Stravinsky's Octet and Symphonies of Wind Instruments. Here neoclassical gestures are supplemented by several quasi-improvisatory and extended instrumental techniques. All ten players are given a chance to shine in solos, and there is plenty of virtuoso passagework. The Adagio mesto creates a mournful misterioso atmosphere with low muted brass supporting exotic wind melodies. As in the first movement, there is judicious use of techniques culled from the notational and orchestrational experiments of the Sixties and Seventies. -

F. Ludwig Diehn Concert Series: the American Brass Quintet

Old Dominion University 2019-2020 F. Ludwig Diehn Concert Series The American Brass Quintet Kevin Cobb, trumpet Louis Hanzlik, trumpet Eric Reed, horn Michael Powell, trombone John D. Rojak, bass trombone Concert: February 17, 7:30 p.m. Master Class: February 18, 12:30 p.m. Wilson G. Chandler Recital Hall F. Ludwig Diehn Center for the Performing Arts arts@odu Program Three Madrigals ........................Luca Marenzio (1553–1599) Scendi dal paradiso (edited by Raymond Mase) Qual mormorio soave Gia torna a rallegrar Chansons ...........................Josquin des Prés (c. 1440–1521) En l’ombre d’ung buissonet (edited by Raymond Mase) El grillo Plaine de dueil De tous biens playne Kanon; N’esse pas ung grant deplaisir The Glow that Illuminates, the Glare that Obscures (2019) ................Nina C. Young (b. 1984) Intermission Luminosity .................................. Jessica Meyer (b. 1974) Fantasia e Rondó. Osvaldo Lacerda (1927–2011) Colchester Fantasy (1987) ......................Eric Ewazen (b. 1954) The Rose and Crown The Marquis of Granby The Dragoon The Red Lion The American Brass Quintet is represented by Kirshbaum Associates, New York. arts@odu This program is funded by an endowment established at the Hampton Roads Community Foundation and made possible by a generous gift from F. Ludwig Diehn. Biography Hailed by Newsweek as “the high priests of brass,” the American Brass Quintet is inter- nationally recognized as one of the era’s premier chamber music ensembles. “The most distinguished” of brass quintets (American Record Guide), the group has earned its stellar reputation through its celebrated performances, genre-defining commissioned works, and ongoing commitment to the education of generations of musicians. -

Music for Brass Quintet with Orchestral Accompaniment: Commissioned Works, the Annapolis Brass Quintet, and a Survey of Literature for Brass Quintet and Orchestra

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2016 MUSIC FOR BRASS QUINTET WITH ORCHESTRAL ACCOMPANIMENT: COMMISSIONED WORKS, THE ANNAPOLIS BRASS QUINTET, AND A SURVEY OF LITERATURE FOR BRASS QUINTET AND ORCHESTRA Stacy L. Simpson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: http://dx.doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2016.269 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Simpson, Stacy L., "MUSIC FOR BRASS QUINTET WITH ORCHESTRAL ACCOMPANIMENT: COMMISSIONED WORKS, THE ANNAPOLIS BRASS QUINTET, AND A SURVEY OF LITERATURE FOR BRASS QUINTET AND ORCHESTRA" (2016). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 67. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/67 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known.