Creating Spaces for Negotiation at the Environment And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Outside 180 Red X4.Cdr

Eremophila bignoniiflora - Creek Wilga * Callitris glaucophylla - Murray Pine S K FTHO Eremophila deserti - Turkey Bush * Callitris gracilis - Slender Cypress Pine FT HO WILDFLOWERS FOR CUT FLOWERS Eremophila longifolia - Berrigan Emu Bush * Callitris rhomboidea - Port Jackson Pine FTHO These plants available all year, fresh cut flowers avaliable in season. Eremophila maculata * Callitris verrucosa M Exocarpos cupressiformis * Eucalyptus albens - White Box FTHO Acacia cultriformis - Cut-leaf Wattle - yellow Eucalyptus crenulata, E. gunnii, E. pulverulenta, Exocarpos stricta - Pale Fruit Ballart * Eucalyptus angulosa M Acacia merinthophora - yellow E. albida and E. - ‘Moon Lagoon’ - silver/blue foliage Geijera parviflora - Wilga * Eucalyptus aromaphloia - Scent Bark FTHO Actinotus helianthi - Flannel Flower - cream * Grevillea - 'Evelyn's Coronet' - pink/grey * Goodenia ovata - Hop Goodenia * W Eucalyptus baxteri - Brown Stringybark FTHO Agonis linearifolia - white Grevillea - 'Sylvia' - pink NATIVE NURSERY Goodia lotifolia - Golden Tip Eucalyptus behriana - Bull Mallee K FTHO Agonis parviceps - white Guichenotia macrantha - *Large-flowered Guichenotia - mauve Goodia medicaginea - Western Golden Tip R Eucalyptus blakelyi - Blakely's Red Gum FTHO Anigozanthos - Kangaroo Paws - red, orange, pink, Hakea multilineata - Grass-leaved Hakea - pink * Hakea decurrens subsp. physocarpa - Bushy Needlewood Eucalyptus calycogona - Red Mallee M FTHO yellow or green * Hypocalymma angustifolium - White Myrtle - cream * Hakea leucoptera M Eucalyptus camaldulensis -

Cattle Creek Ecological Assessment Report

CATTLE CREEK CCCATTLE CCCREEK RRREGIONAL EEECOSYSTEM AND FFFUNCTIONALITY SSSURVEY Report prepared for Santos GLNG Feb 2021 Terrestria Pty Ltd, PO Box 328, Wynnum QLD 4178 Emai : admin"terrestria.com.au This page left blank for double-sided printing purposes. Terrestria Pty Ltd, PO Box 328, Wynnum QLD 4178 Emai : admin"terrestria.com.au Document Control Sheet Project Number: 0213 Project Manager: Andrew Daniel Client: Santos Report Title: Cattle Creek Regional Ecosystem and Functionality Survey Project location: Cattle Creek, Bauhinia, Southern Queensland Project Author/s: Andrew Daniel Project Summary: Assessment of potential ecological constraints to well pad location, access and gathering. Document preparation and distribution history Document version Date Completed Checked By Issued By Date sent to client Draft A 04/09/2020 AD AD 04/09/2020 Draft B Final 02/02/2021 AD AD 02/02/2021 Notice to users of this report CopyrighCopyright: This document is copyright to Terrestria Pty Ltd. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Terrestria Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the express permission of Terrestria Pty Ltd constitutes a breach of the Copyright Act 1968. Report LimitationsLimitations: This document has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of Santos Pty Ltd. Terrestria Pty Ltd accept no liability or responsibility whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. Signed on behalf of Terrestria Pty Ltd Dr Andrew Daniel Managing Director Date: 02 February 2021 Terrestria Pty Ltd File No: 0213 CATTLE CREEK REGIONAL ECOSYSTEM AND FUNCTIONALITY SURVEY Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... -

Species List

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Grassy Woodlands of the Goulburn Broken Catchment

INTRODUCTION GRASSY WOODLANDS OF THE GOULBURN BROKEN CATCHMENT IDENTIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK 1 Contributions: Coordination, Species descriptions: Wendy D’Amore (Euroa Arboretum); Additional species descriptions: Cathy Olive, Lance Williams (Euroa Arboretum); Introduction: Lance Williams Photographers: Gratefully acknowledged and listed underneath their photos. Photos were also sourced from NatureShare, where individual contributors are acknowledged, and from the Native Vegetation of the Goulburn Broken Riverine Plains (NVGBRP) publication. Copyright for the images remain with the photographers. Photos Front Cover: Jim Begley, Stephen Prothero Edited by: Jenny Wilson (Goulburn Broken CMA), Cathy Olive and Kate Stothers (Euroa Arboretum) ISBN: 978-1-876600-06-8 This publication is supported by the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority through funding from the Australian Government’s National Landcare Programme. 2 INTRODUCTION Contents Introduction 2 Grassy Woodlands - their ‘original’ condition 3 What is a woodland? 5 Where are these woodlands, and what do they look like? 6 Management of Grassy Woodlands 8 How this booklet is arranged 8 Flora Species 9 n Grasses 10 n Groundcovers and Herbs 30 n Shrubs Below 1m 68 n Shrubs 1-8m 96 n Trees 119 Appendices 136 Glossary 141 Flora Species Index 143 References 147 Further Reading 148 1 INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION 2 INTRODUCTION Grassy Woodlands - their ‘original’ condition The early European explorers and settlers in northern Victoria recorded - to a greater or lesser extent - their observations of the woodlands that they encountered in the early 19th century. Their descriptions provide us with the earliest written accounts of the appearance of these areas before European-imposed stock grazing, vegetation clearance and altered fire regimes transformed these landscapes. -

Biodiversity Summary: Wimmera, Victoria

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Drayton Management System Standard Rehabilitation and Offset

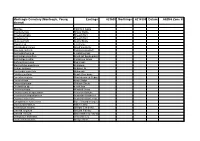

Anglo Coal (Drayton Management) Pty Ltd Policies and Procedures Rehabilitation and Offset Management Plan Drayton Management System Standard Rehabilitation and Offset Management Plan Author: Name Brooke York Title Environmental Officer Signature (B York) Date (29.10.13) Reviewer: Name Peter Forbes Title SHE Manager Signature (P Forbes) Date (30.10.13) Authoriser: Name Clarence Robertson Title General Manager Signature (C Robertson) Date (1.11.13) This document is controlled whilst it remains in the Drayton Intranet Printed copies created from this document are deemed to be uncontrolled Rehabilitation and Offset Management Plan Page 1 of 48 Revisions Issue Issue Date Author Reviewer Authoriser 1 October 2009 D Robertson P Simpson M Heaton 2 January 2013 B Lavis P Forbes C Robertson 3 October 2013 B York P Forbes C Robertson Rehabilitation and Offset Management Plan Page 2 of 48 Distribution List Distributed to: General Manager’s Office (current originals) All Drayton Employees via Email or Toolbox Talks Administration Central File (originals of previous versions) Department of Planning and Infrastructure NSW Muswellbrook Shire Council Department of Trade and Investment – Resources and Energy Rehabilitation and Offset Management Plan Page 3 of 48 Table of Contents 1 PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................................... 6 2 SCOPE .......................................................................................................................................... -

Native Vegetation of the Goulburn Broken Riverine Plains

Native Vegetation of the Goulburn Broken Riverine Plains Native Vegetation of the Goulburn Broken Riverine Plains This project is delivered and funded primarily through the partnerships between the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority (GBCMA), Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Goulburn Murray Landcare Network (GMLN), Greater Shepparton City Council, Shire of Campaspe and Moira Shire. Published by: Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority 168 Welsford St, Shepparton, Victoria, Australia August 2012 ISBN: 978-1-920742-25-6 Acknowledgments The Goulburn Broken CMA and the GMLN gratefully acknowledge the staff of the Sustainable Irrigated Landscapes - Goulburn Broken, Environmental Management Team, particularly Fiona Copley who compiled the first edition “Native Vegetation in the Shepparton Irrigation Region” based on research of literature (References page 95) and communication with recognised flora scientists. Special acknowledgement goes to the GMLN in partnership with the Shepparton Irrigation Region Implementation Committee for enabling the printing of the first edition. The second edition, renamed “Native Vegetation of the Goulburn Broken Riverine Plains” was updated by Wendy D’Amore, GMLN with additions and subtractions made to the plant list and the booklet published in a new format. Special thanks to Sharon Terry, Rolf Weber, Joel Pyke and Gary Deayton for their expert knowledge of the plants and their distribution in the Riverine Plains. Many thanks also to members of the GMLN, Goulburn Broken CMA, DPI and Goulburn Valley Printing Services for their advice and assistance. Photo credits In this edition many plant profiles had their photographs updated or added to and additional species were added. The following photographers are gratefully acknowledged: Sharon Terry, Phil Hunter, Judy Ormond, Andrew Pearson, Keith Ward, Janet Hagen, Gary Deayton, Danielle Beischer, Bruce Wehner and Wendy D’Amore. -

Site Species List

Monteagle Cemetery (Monteagle, Young Eastings: 623600 Northings: 6214300 Datum: AGD66 Zone 55 district) Species Common name Acacia decora Showy Wattle Acaena agnipila Sheep's Burr Acaena ovina Sheep's Burr Ajuga australis Austral Bugle Amyema sp. a mistletoe Arthropodium minus Small Vanilla-lily Asperula conferta Common woodruff Austrodanthonia sp. a wallaby grass Austrostipa densiflora Brush-tail Spear-grass Austrostipa scabra Corkscrew Grass Bothriochloa macra Red Grass Brachychiton populneus Kurrajong Bulbine bulbosa Bulbine Lily Burchardia umbellata Milkmaids Calotis cuneifolia Purple Burr-daisy Carex breviculmis Short-stemmed Sedge Carex inversa Knob Sedge Cassinia arcuata Chinese Shrub Cheilanthes sp. a rock fern Chloris truncata Windmill Grass Chrysocephalum apiculatum Common Buttons Convolvulus angustissimus Australian Bindweed Crassula sieberiana Australian Stone-crop Cynoglossum suaveolens Sweet Hound's-tongue Daucus glochidiatus Native Carrot Desmodium varians Slender Tick-trefoil Dianella longifolia Smooth Flax-lily Dianella revoluta Black-anthered Flax-lily Dichopogon fimbriatus Chocolate Lily Diuris dendrobioides Wedge Diuris Diuris punctata Purple Diuris Drosera peltata Pale Sundew Elymus scaber Common Wheat-grass Epilobium sp. Willowherb Eriochilus cucullatus Parson's Bands Eryngium rostratum Blue Devil Eucalyptus albens White Box Eucalyptus blakelyi Blakely's Red Gum Eucalyptus bridgesiana Apple Box Eucalyptus melliodora Yellow Box Geranium retrorsum Native Geranium Glycine tabacina Vanilla Glycine Goodenia hederacea Ivy -

Volume 4 Appendix HA Flora Assessment

WILPINJONG COAL PROJECT APPENDIX HA Flora Assessment Wilpinjong Coal Project APPENDIX HA WILPINJONG COAL PROJECT FLORA ASSESSMENT PREPARED BY FLORASEARCH MARCH 2005 Document No. APPENDIX HA-Q.DOC Wilpinjong Coal Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page HA1 INTRODUCTION HA-1 HA1.1 SURVEY OBJECTIVES HA-1 HA1.2 REGIONAL SETTING HA-1 HA1.3 DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA AND SURROUNDS HA-1 HA1.3.1 Topography and Drainage HA-1 HA1.3.2 Geology and Soils HA-5 HA1.3.3 Climate HA-5 HA1.3.4 Landuse HA-6 HA1.4 BOTANICAL/BIOGEOGRAPHICAL REGIONS HA-6 HA1.5 PREVIOUS VEGETATION STUDIES HA-7 HA1.6 CONSERVATION STATUS OF THE REGIONAL FLORA HA-7 HA1.6.1 Conservation Reserves HA-7 HA1.6.2 Threatened Vegetation Communities, Populations and Species HA-7 HA2 METHODS HA-8 HA2.1 VEGETATION SAMPLING HA-8 HA2.1.1 Quadrat Sampling HA-8 HA2.1.2 Spot Sampling HA-12 HA2.2 VEGETATION MAPPING HA-12 HA2.2.1 General Mapping HA-12 HA2.2.2 Threatened Community Mapping HA-12 HA2.3 SPECIES LISTING HA-13 HA2.4 ASSESSMENT OF VEGETATION CONDITION HA-13 HA3 RESULTS HA-13 HA3.1 VEGETATION COMMUNITIES HA-13 HA3.1.1 Community 1 - Yellow Box and Blakely’s Red Gum Woodlands HA-13 HA3.1.2 Community 2 - Coast Grey Box Woodlands HA-17 HA3.1.3 Community 3 - Rough-barked Apple Woodlands HA-18 HA3.1.4 Community 4 – Narrow-leaved Ironbark Forest HA-19 HA3.1.5 Community 5 - White Box Woodlands HA-20 HA3.1.5.1 Community 5a - Grassy White Box Woodlands HA-20 HA3.1.5.2 Community 5b - Shrubby White Box Woodlands HA-21 HA3.1.6 Community 6 - Sandstone Range Shrubby Woodlands HA-21 HA3.1.7 Community -

Dubbo Region Flora List 2012

Flora List of the Dubbo Area and Central Western Slopes Harlequin Mistletoe Lysiana exocarpi subsp. tenuis Drilliwarrina State Conservation Area Janice Hosking for the Dubbo Field Naturalist and Conservation Society Inc Version: June 2012 www.dubbofieldnats.org.au Flora List of the Dubbo Area and Central Western Slopes Janice Hosking for Dubbo Field Nats This list of approximately 1,300 plant species was prepared by Janice Hosking for the Dubbo Field Naturalist & Conservation Society Inc. Many thanks to Steve Lewer and Chris McRae who spent many hours checking and adding to this list. Cover photo: Anne McAlpine, A map of the area subject to this list is provided below. Data Sources: This list has been compiled from the following information: A Flora of the Dubbo District 25 Miles radius around the city (c. 1950s) compiled by George Althofer, assisted by Andy Graham. Gilgandra Native Flora Reserve Plant List Goonoo State Forest Forestry Commission list, supplemented by Mr. P. Althofer. List No.1 (c 1950s) Goonoo State Forest Dubbo Management Area list of Plants List No.2 The Flora of Mt. Arthur Reserve, Wellington NSW A small list for Goonoo State Forest. Author and date unknown Flora List from Cashells Dam Area, Goonoo State Forest (now CCA) – compiled by Steve Lewer (NSW OEH) Oasis Reserve Plant List (Southwest of Dubbo) – compiled by Robert Gibson (NSW OEH) NSW DECCW Wildlife atlas List 2010,Y.E.T.I. List 2010 PlantNet (NSW Botanic Gardens Records) Various species lists for Dubbo District rural properties – compiled by Steve Lewer (NSW OEH) * Denotes an exotic species ** Now considered to be either locally extinct or possibly a misidentification. -

Flora of South Australia 5Th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann

Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann FABACEAE (LEGUMINOSae) (partly)1 I.R. Thompson2 & P.G. Wilson3 Treatments of Fabaceae presented here include tribes Bossieae, Brongniartieae and Indigofereae. Other groups are in preparation and will be made available once finalized. — Ed. TRIbe BOSSIaeeae (Benth.) Hutch. Prepared by I.R. Thompson Small trees, shrubs, subshrubs, or perennial herbs, with branches occasionally armed (not in S.A.), without glandular material in axils; leaves alternate or opposite, petiolate, 1–3-foliolate, imparipinnate, or absent; stipules present, free, persistent or caducous, sometimes fusing to form a scale; lamina of leaflets mostly entire; leaflets short-petiolulate, estipellate. Inflorescences terminal or pseudoaxillary, comprising few- to many-flowered racemes or flowers solitary; sometimes with scales below; flowers pedicellate; bract basal or near-basal; bracteoles persistent or caducous; calyx with tube variable in length relative to lower lobes; lobes imbricate in bud, upper lobes ± free or variously fused, sometimes relatively broad and/or long; petals clawed; stamens forming an adaxially open sheath, anthers uniform, versatile; ovary mostly few–several-ovulate. Pods dehiscent, predominantly stipitate, body oblong to elliptic in profile, moderately to strongly compressed, valves variably rigid, with thinner valves sometimes rolling on dehiscence, rarely with internal partitions; seeds with hilum short, c. lateral, mostly arillate; aril hood-like. 7 genera and c. 104 species, all endemic in Australia. Hovea and Templetonia, included in this tribe in Jessop & Toelken (1986), are now in the tribe Brongniartieae. 1. Leaves trifoliolate 2. Plants erect, c. 1–3 m high; inflorescences many-flowered ........................................................................ 3. Goodia 2: Plants prostrate; inflorescences 1- or 2-flowered .......................................................................... -

Ecology of Sydney Plant Species Part 4: Dicotyledon Family Fabaceae

552 Cunninghamia Vol. 4(4): 1996 M a c q u a r i e R i v e r e g n CC a Orange R Wyong g n i Gosford Bathurst d i Lithgow v Mt Tomah i Blayney D R. y r Windsor C t u a o b Oberon s e x r e s G k Penrith w a R Parramatta CT H i ve – Sydney r n a Abe e Liverpool rcro p m e b Botany Bay ie N R Camden iv Picton er er iv R y l l i Wollongong d n o l l o W N Berry NSW Nowra 050 Sydney kilometres Figure 1. The Sydney region For the Ecology of Sydney Plant Species the Sydney region is defined as the Central Coast and Central Tablelands botanical subdivisions. Benson & McDougall, Ecology of Sydney plant species 4: Fabaceae 553 Ecology of Sydney Plant Species Part 4 Dicotyledon family Fabaceae Doug Benson and Lyn McDougall Abstract Benson, Doug and McDougall, Lyn (National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, Australia 2000) 1996 Ecology of Sydney Plant Species: Part 4 Dicotyledon family Fabaceae. Cunninghamia 4(4) 553–000. Ecological data in tabular form is provided on 311 plant species of the family Fabacae, 243 native and 68 exotics, mostly naturalised, occurring in the Sydney region, defined by the Central Coast and Central Tablelands botanical subdivisions of New South Wales (approximately bounded by Lake Macquarie, Orange, Crookwell and Nowra). Relevant Local Government Areas are Auburn, Ashfield, Bankstown, Bathurst, Baulkham Hills, Blacktown, Blayney, Blue Mountains, Botany, Burwood, Cabonne, Camden, Campbelltown, Canterbury, Cessnock, Concord, Crookwell, Drummoyne, Evans, Fairfield, Greater Lithgow, Gosford, Hawkesbury, Holroyd, Hornsby, Hunters Hill, Hurstville, Kiama, Kogarah, Ku-ring-gai, Lake Macquarie, Lane Cove, Leichhardt, Liverpool, Manly, Marrickville, Mosman, Mulwaree, North Sydney, Oberon, Orange, Parramatta, Penrith, Pittwater, Randwick, Rockdale, Ryde, Rylstone, Shellharbour, Shoalhaven, Singleton, South Sydney, Strathfield, Sutherland, Sydney City, Warringah, Waverley, Willoughby, Wingecarribee, Wollondilly, Wollongong, Woollahra and Wyong.