Digital Economy Digital Workplaces in Outer Regional, Remote and Very Remote Areas of Australia: Experiences from the NT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal Interpreter Service

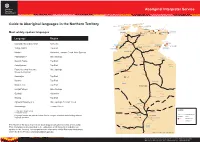

Aboriginal Interpreter Service CROKER ISLAND Guide to Aboriginal languages in the Northern Territory MELVILLE ISLAND Iwaidja GOULBURN ISLANDS BATHURST ISLAND Maung Tiwi ELCHO ISLAND GALIWIN’KU WURRUMIYANGA Ndjebbana MILINGIMBI MANINGRIDA NHULUNBUY DARWIN Burarra Yolngu Matha YIRRKALA Most widely spoken languages GUNBALANYA Kunwinjku RAMINGINING GAPUWIYAK JABIRU Language Region UMBAKUMBA East Side/West Side Kriol Katherine Ngan'gikurrunggurr Nunggubuyu ANGURUGU GROOTE EYLANDT WADEYE East Side Kriol KATHERINE NUMBULWAR Yolngu Matha Top End Anindilyakwa Murrinh Patha NGUKURR West Side Kriol URAPUNGA Warlpiri Katherine, Tennant Creek, Alice Springs HIGHWAY Pitjantjatjara Alice Springs VICTORIA Yanyuwa BORROLOOLA Murrinh Patha Top End Ngarinyman Anindilyakwa Top End Garrwa DAGURAGU Eastern/Central Arrernte, Alice Springs STUART Gurindji Western Arrarnta + KALKARINDJI ELLIOTT Kunwinjku Top End LAJAMANU HIGHWAY Burarra Top End Warumungu Warlpiri BARKLY Modern Tiwi Top End TENNANT CREEK HIGHWAY Luritja/Pintupi Alice Springs Gurindji Katherine ALI CURUNG Alyawarr Maung Top End Alyawarr/Anmatyerr + Alice Springs, Tennant Creek Anmatyerr Warumungu Tennant Creek YUENDUMU Luritja/Pintupi LEGEND Western Desert family PAPUNYA + Arandic family Western Tiwi...................LANGUAGE GROUP Language families are indicated where there is a degree of mutual understanding between Arrarnta ALICE SPRINGS JABIRU .........TOWN language speakers. HERMANNSBURG Eastern/Central Arrernte ELLIOTT ............REMOTE TOWN BARUNGA .........COMMUNITY The Northern Territory -

2015-2016 Annual Report

Central Desert Regional Council 2015–16 ANNUAL REPORT The Story of the Front Cover The cover of this year’s annual report shows the Anmatjere Roads Team and Community Development Program (CDP) participants and local community members celebrating the opening of the Nturiya Road. Due to heavy rains in January 2015, the Nturiya Road was badly damaged making access to the community difficult and dangerous. Works to reinstate the road were possible thanks to funding provided by the Natural Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangements funding. The Nturiya Road reinstatement project demonstrates how Central Desert Regional Council actively works to ensure that projects deliver maximum community benefit as well as value for money for community members and funding bodies. Working Nturiya Road, Anmatjere: flood damage reinstatement work. cooperatively with local businesses, training providers and across different programs within the Council, the Nturiya Road project was a success on multiple fronts. The work undertaken by the Council’s Works team was of a high standard and demonstrated the Council’s ability to undertake works of this calibre. A further nine men from the Community Development Program (CDP), worked alongside private contractors and the Council’s own Works team as part of a Certificate III in Civil Construction training program. The training program, delivered in association with Charles Darwin University, saw the participants not only learn valuable skills, but also significantly contribute to important community projects. Skills learnt as part of the training course have enabled the men Anmatjere’s Morgan Abbott, Maureen van Heusden, Apprentice to operate heavy machinery, including backhoes, bobcats, vibe of the Year Jacko Long and Peter van Heusden at the GTNT Award rollers, tipper trucks, semi trailers, graders and front end loaders. -

Victoria Daly Regional Plan 2019-20

Victoria Daly Regional Council Regional Plan 2019-20 Table of Contents From Our Mayor ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Council’s Elected Members ................................................................................................................... 5 From our CEO ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Our Vision, Mission and Core Values .................................................................................................... 8 Vision ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Mission .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Core Values ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Goals .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Governance ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Constitutional arrangement ............................................................................................................. -

Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Visions and Violence of Policy An ethnography of Indigenous Affairs bureaucratic reform in the Northern Territory of Australia Thomas Michel Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 1 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. I declare my previously published works are: Michel, T. (2018). The Lifeblood of the Cyborg: Or, the shared organism of a modern energy corporation and a small Northern Territory town. Energy Research & Social Science, 45 (November 2018), 224-234. Michel, T. (2016). Cyborg Wadeye. Arena Magazine, 142, 34-37. Michel, T. (2015). The Special Case of Reform in the Northern Territory: What Are The Lessons? In I. Tiley & B. Dollery (Eds.), Perspectives on Australian Local Government Reform. Sydney: Federation Press. Michel, T., & Bassinder, J. A. (2013). Researching with Reciprocity: Meaningful Participant- Based Research in a Remote Indigenous Community Context. Paper presented at the Australian Centre of Excellence for Local Government (ACELG) 3rd National Local Government Researchers' Forum, 6-7 June 2013, University of Adelaide, South Australia. http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ocs/index.php/acelg/PNLGRF/paper/view/478 Michel, T., & Taylor, A. (2012). Death by a thousand grants? The challenge of grant funding reliance for local government councils in the Northern Territory of Australia. -

Select Committee on the Effectiveness of the Australian Government's

The Senate Select Committee on the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s Northern Australia agenda Select Committee on the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s Northern Australia agenda Final report April 2021 © Commonwealth of Australia ISBN 978-1-76093-219-0 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Printed by Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. Members Chair Senator Murray Watt ALP, QLD Deputy Chair Senator Susan McDonald NATS, QLD Members Senator Patrick Dodson ALP, WA Senator Malarndirri McCarthy ALP, NT Senator Malcolm Roberts PHON, QLD Senator Rachel Siewert AG, WA Senator Dean Smith LP, WA Secretariat Ms Lee Katauskas, Committee Secretary Ms Fattimah Imtoual, Principal Research Officer Ms Adrienne White, Senior Research Officer Ms Ella Ross, Administrative Officer iii Contents Members ............................................................................................................................................. iii Terms of Reference .......................................................................................................................... vii Abbreviations and acronyms ........................................................................................................... ix List of Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Kunmanggur, Legend and Leadership a Study of Indigenous Leadership and Succession Focussing on the Northwest Region of the North

KUNMANGGUR , LEGEND AND LEADERSHIP A STUDY OF INDIGENOUS LEADERSHIP AND SUCCESSION FOCUSSING ON THE NORTHWEST REGION OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Bill Ivory Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Charles Darwin University 2009 Declaration This is to certify that this thesis comprises only my original work towards the Ph.D., except where indicated, that due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other materials used, and that this thesis is less than 100,000 words in length excluding Figures, Tables and Appendices. Bill Ivory 2009 ii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my supervisors Kate Senior, Diane Smith and Will Sanders. They have been extremely supportive throughout this research process with their expert advice, enthusiasm and encouragement. A core group of Port Keats leaders supported this thesis project. They continually encouraged me to record their stories for the prosperity of their people. These people included Felix Bunduck, Laurence Kulumboort, Bernard Jabinee, Patrick Nudjulu, Leo Melpi, Les Kundjil, Aloyisius Narjic, Bede Lantjin, Terence Dumoo, Ambrose Jongmin. Mathew Pultchen, Gregory Mollinjin, Leo Melpi, Cassima Narndu, Gordon Chula and many other people. Sadly, some of these leaders passed away since the research commenced and I hope that this thesis is some recognition of their extraordinary lives. Boniface Perdjert, senior traditional owner and leader for the Kardu Diminin clan was instrumental in arranging for me to attend ceremonies and provided expert information and advice. He was also, from the start, very keen to support the project. Leon Melpi told me one day that he and his middle-aged generation are „anthropologists‟ and he is right. -

Victoria Daly Shire Council

Victoria Daly Shire Council Service Delivery Plan Period: 08/09 - 12/13 v3.2.2 VICTORIA DALY SHIRE BUSINESS STRUCTURE AND SERVICE DELIVERY PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS May 2008 DIRECTORATE: Chief Executive and Governance DIRECTORATE: Corporate and Community Services DIRECTORATE: Infrastructure and Civil Services Business Unit: Chief Executive and Shire Services Management Business Unit: Financial and Corporate Management Business Unit: Assets Core - Local Emergency Management (PAGE 4) Core - Council Planning and Reporting (PAGE 118) Core - Asset Management (PAGE 135) Core - Shire Services Management (PAGE 8) Core - Financial Management (PAGE 121) Core - Fleet and Plant Maintenance and Management (PAGE 137) Core - Maintenance and Upgrade of Council-controlled buildings, facilities and fixed Business Unit: Governance Core - Information Technology and Communications (PAGE 124) assets (PAGE 141) Agency - Economic Development Support (PAGE 11) Core - Revenue Growth (PAGE 126) Business Unit: Civil Services Core - Administration of Council Meetings, Local Boards and Sub Committees (PAGE 13) Business Unit: Human Resources and Training Agency - Airstrips Maintenance (PAGE 212) Core - Adminstration of Local Laws (PAGE 15) Core - Human Resources Management (PAGE 128) Agency - Environmental Health and Life Skills (PAGE 218) Core - Training and Employment of Local People in Council Operations (PAGE Core - Advocacy and Representation on Local and Regional Issues (PAGE 18) 131) Agency - Natural Resource Management (PAGE 220) Core - Community Information and -

NT CRICKET 2016 / 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Front Cover Image: Australian Cricket Team - Player Engagement Day NT CRICKET 2016 / 2017 ANNUAL REPORT

NT CRICKET 2016 / 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Front cover image: Australian Cricket team - player engagement day NT CRICKET 2016 / 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Contents President’s Report 4 CEO’s Report 6 About NT Cricket 8 Our People 9 Australian Cricket Team Training Camp 10 2017 Sheffield Shield 12 2017 Sheffield Shield Final 13 Bangladesh Academy Visit 14 Strike League/SLO1 16 Game and Market Development 18 Schools 19 Remote Red Dust Sports Voucher Program 20 Remote Cricket 21 Remote Community Cricket Carnivals 24 National Indigenous Cricket Championships 27 Northern Territory NICC Teams 28 2017 Imparja Cup 30 Coach Education 32 NT Emerging Players 33 NT Strike - SACA Redbacks League 34 Australian Country Cricket Championships 35 NT Under 19s 36 NT Under 17s 37 School Sport Australia Under Age Championships 38 Darwin and Districts Cricket Competition 43 Alice Springs Cricket Association 44 Katherine District Cricket Competition 45 Tennant Creek Cricket Association 46 Northern Territory Umpires 47 Curator’s Report 48 Sponsors 50 Financial Report 52 Growing Cricket in the North | 3 President’s Report On behalf of the Board, I am pleased to report on NT Cricket’s activities for 2016 - 17. The past year has been one where the Board of NT Cricket has undertaken a number of activities to prepare for the future growth of the game as we look to Grow the Game in the North. Our focus has been on governance, our objects and Board renewal. As advised at last years AGM, the Board is proposing to bring a recommendation to the members that NT Cricket adopts a new governance structure as a Company Limited by Guarantee. -

Submission to the Select Committee on the Effectiveness of the Australian Government’S Northern Australia Agenda

Submission to the Select Committee on the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s northern Australia agenda The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science thanks the Select Committee for the opportunity to provide this submission, which outlines the progress made under the Australian Government’s northern Australia economic development agenda. Department of Industry, Innovation and Science The Department of Industry, Innovation and Science is focused on economic transformation and boosting Australia’s competitiveness by backing business, science, innovation and investment. The department works to position Australian businesses to harness the opportunities presented by technological change and global economic growth. Equally important is the department’s responsibility to help people navigate these changes by ensuring policies and programs pave the way for businesses to create jobs across all parts of the economy. The Office of Northern Australia (ONA) is a branch within the department. The ONA has responsibility for leading the Australian Government’s northern Australia agenda, working across all levels of government to implement measures under the White Paper on Developing Northern Australia, and the economic development agenda more broadly. Implementation of initiatives occurs at various levels, across the Commonwealth, state and territory governments and, industry, economic development, research and academic sectors. The ONA provides coordination and leadership to achieve strategic outcomes, minimising duplication, and broadening objectives to achieve maximum development potential. The ONA has staff in Darwin, Broome, Cairns, Townsville, Brisbane and Canberra. This footprint enables the views of northern Australian residents to be heard in a nationally significant policy agenda. ONA’s northern presence models meaningful and agile stakeholder engagement and collaboration, which responds quickly to emerging barriers and opportunities. -

Justice Reinvestment in Katherine

JUSTICE REINVESTMENT IN KATHERINE Report on Initial Community Consultations Fiona Allison Research Fellow James Cook University July 2016 1 JUSTICE REINVESTMENT IN KATHERINE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. JR PROJECT IN KATHERINE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Justice Reinvestment 1.2.1 JR as an alternative strategy 1.2.2 The four stages of JR 1.3 Our project methodology 1.3.1 Gathering project data 1.3.2 Collective impact framework 1.3.3 Identifying the JR ‘community’ 2. SUMMARY OF DATA 2.1 Strengths-based approach 2.2 Community interest in and support for JR in Katherine 2.3 Offending and incarceration in Katherine: nature and impacts 2.3.1 Offending and incarceration in Katherine 2.3.2 Impacts of offending and incarceration in Katherine 2.4 Social drivers of offending/incarceration in Katherine 2.4.1 Boredom and connection 2.4.2 Mental health, disability, alcohol/substances 2.4.3 Family issues 2.4.4 Education and employment 2.4.5 Indigenous disempowerment 2.5 Drivers of offending/incarceration within the justice system in Katherine 2.5.1 Justice system 2.5.2 Police diversion 2.5.3 Eligibility for and completion of diversionary orders 2.5.4 Post-release and detention 2.6 Community-based responses to offending and incarceration 2.6.1 Addressing boredom and the need for belonging 2.6.2 Responding to family, mental health, disability and substance/alcohol issues 2.6.3 Indigenous community-led responses outside the justice system 2.6.4 Education 2.6.5 Economic development and employment 2.7 Justice responses to offending and incarceration 2.7.1 Extending and increasing effectiveness of diversionary options 2 2.7.2 Detention and post-release 2.7.3 Youth Hub 2.8 Indigenous leadership and empowerment 2.8.1 Mentoring 2.8.2 Camps 2.8.3 Sentencing of offenders and courts: Indigenous input 2.9 Conclusion BIBLIOGRAPHY Appendix A: Project Documents Appendix B: Statistics Appendix C: List of consultations Appendix D: Consultation questions Appendix E: JR ‘Wheel’ 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. -

Project Sea Dragon Stage 1 Legune Grow-Out Facility Draft Environmental Impact Statement

PROJECT SEA DRAGON STAGE 1 LEGUNE GROW-OUT FACILITY DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT VOLUME 5 - APPENDICES APPENDIX 21 -ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT Volume 5 - Appendices Appendix 21 -Economic Impact Assessment 1 REPORT TO SEAFARMS GROUP LIMITED 5 JULY 2016 PROJECT SEA DRAGON SOCIO-ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT STAGE 1 – LEGUNE GROW-OUT FACILITY ACIL ALLEN CONSULTING PTY LTD ABN 68 102 652 148 LEVEL FIFTEEN 127 CREEK STREET BRISBANE QLD 4000 AUSTRALIA T+61 7 3009 8700 F+61 7 3009 8799 LEVEL TWO 33 AINSLIE PLACE CANBERRA ACT 2600 AUSTRALIA T+61 2 6103 8200 F+61 2 6103 8233 LEVEL NINE 60 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE VIC 3000 AUSTRALIA T+61 3 8650 6000 F+61 3 9654 6363 LEVEL ONE 50 PITT STREET SYDNEY NSW 2000 AUSTRALIA T+61 2 8272 5100 F+61 2 9247 2455 LEVEL TWELVE, BGC CENTRE 28 THE ESPLANADE PERTH WA 6000 AUSTRALIA T+61 8 9449 9600 F+61 8 9322 3955 161 WAKEFIELD STREET ADELAIDE SA 5000 AUSTRALIA T +61 8 8122 4965 ACILALLEN.COM.AU FOR INFORMATION ON THIS REPORT PLEASE CONTACT: CONTRIBUTING TEAM MEMBERS (ALPHABETICAL) Guy Jakeman ANTONIA HODBY E: [email protected] GUY JAKEMAN Office: +61 2 6103 8200 | D: +61 2 6103 8202 | M: 0417 706 522 DR PETER JOHNSON RELIANCE AND DISCLAIMER THE PROFESSIONAL ANALYSIS AND ADVICE IN THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PREPARED BY ACIL ALLEN CONSULTING FOR THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF THE PARTY OR PARTIES TO WHOM IT IS ADDRESSED (THE ADDRESSEE) AND FOR THE PURPOSES SPECIFIED IN IT. THIS REPORT IS SUPPLIED IN GOOD FAITH AND REFLECTS THE KNOWLEDGE, EXPERTISE AND EXPERIENCE OF THE CONSULTANTS INVOLVED. -

Governance of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Justice Agreement 6 Governance of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Justice Agreement

Governance of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Justice Agreement 6 Governance of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Justice Agreement Central to the governance of the NTAJA is the guiding principle that Aboriginal Territorians have the right to speak, to be heard, and be actively engaged in decision-making processes that impact on Aboriginal people in the NT. A robust governance structure is critical to ensure the signatories to the NTAJA are held accountable and to monitor the Agreement’s effectiveness. In line with the NTAJA’s staged implementation, the Agreement’s governance structure will consist of two distinct phases delivered over seven years. Under NTAJA Stage 1 (2019-2021), an initial governance structure will be established. Following an evaluation, the governance structure will be revised under NTAJA Stage 2 (2022-2025). In all stages of the NTAJA, governance committees will be established to serve as the forum for Aboriginal community representatives to directly discuss Aboriginal justice issues with Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) of NTG agencies. The establishment of local Law and Justice Groups (LJGs) will provide a platform for Aboriginal Territorians to develop culturally-competent, place- based strategies to improve local justice outcomes. The structure proposed below has been developed to reflect the partners’ agreed understanding that only an integrated, Territory-wide, whole-of-government approach will create meaningful change and achieve the Agreement’s aims. 6.1 Governance Overview 6.1.1 Stage 1: 2019-2021 A summary of the governance structure for Stage 1 is outlined below and in Figure 29. The Attorney-General and Minister for Justice will: • oversee the implementation of the NTAJA within the broader justice portfolio • table an annual progress report to Parliament reporting on the outcomes of the NTAJA • communicate and coordinate activities between the Aboriginal Affairs Sub-Committee of Cabinet and the NTAJA Governance Committee.