Evolution of Centre-State Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

Page-1.Qxd (Page 2)

daily Vol No. 49 No. 354 JAMMU, TUESDAY, DECEMBER 24, 2013 REGD.NO.JK-71/12-14 12 Pages ` 3.50 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/1992 SKIMS Director to identify diseases caused by adulterated products Home Secy issues HC imposes Rs 30 cr penalty on advisories ahead companies for food adulteration of election year Fayaz Bukhari its utilization. "In our consid- Director SKIMS, Srinagar to Sanjeev Pargal the upcoming year of 2014 with ered view, at this stage, we file report about the nature of senior officers of BSF, CRPF, SRINAGAR, Dec 23: In a deem it appropriate to direct diseases caused by the colouring JAMMU, Dec 23: Union Intelligence agencies, police and landmark judgment aimed at the owners/Managing and other material which has Home Secretary Anil civil administration, drawn from safeguarding the health of Directors of the above said been found in the spices and the Goswami today called upon both divisions of the State for people, the Jammu and companies, corporations to toned milk. Army, para-military forces, over two hours from 11 am to 1 Kashmir High Court today deposit amount of Rs 10 crore The Government has been police and Intelligence agen- pm. imposed a penalty of Rs 30 each with the Director directed to give wide publicity cies to maintain high level Mr Goswami is reported to crore to three food products SKIMS, Soura, Srinagar with- in the print and electronic media alert in the State including the have shared inputs the MHA manufacturing companies in two weeks from today", about these food items so as to borders ahead of next year's had gathered about security sce- whose products were found directed the court. -

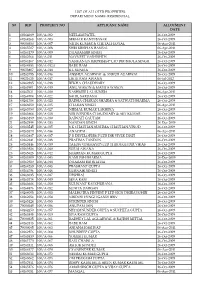

S# Rid Property No Applicant Name Allotment Date 1

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- RESIDENTIAL S# RID PROPERTY NO APPLICANT NAME ALLOTMENT DATE 1 60264689 100/A-002 NEELAM PATEL 26-Oct-2009 2 60264268 100/A-003 SEKHAR KANTI BASAK 26-Oct-2009 3 90000350 100/A-007 NITIN KUMAR & CHETALI GOYAL 06-Apr-2011 4 60265507 100/A-008 SHRI KRISHAN BANSAL 06-Apr-2011 5 60264179 100/A-009 DHARAMBIR SINGH 26-Oct-2009 6 60262564 100/A-011 NAVNEET VASHISHTH 26-Oct-2009 7 60264167 100/A-012 YASIKAN ENTERPRISES P LTD DIR BHOLA SINGH 26-Oct-2009 8 60264553 100/A-012A BABU RAM 26-Oct-2009 9 90023807 100/A-014 K L SUNEJA 26-Oct-2009 10 60265795 100/A-016 ANSHUL AGARWAL & ANKUR AGARWAL 26-Oct-2009 11 90021623 100/A-017 LIKHI RAM AWANA 06-Jul-2012 12 60262985 100/A-018 REKHA CHAUDHARY 26-Oct-2009 13 60263901 100/A-019 ANIL WASON & MAMTA WASON 26-Oct-2009 14 60267621 100/A-020 KASHMIRI LAL SUNEJA 06-Apr-2011 15 60264704 100/A-022 SAHIL SARDANA 26-Oct-2009 16 60261786 100/A-023 RADHA CHARAN SHARMA & SATWATI SHARMA 26-Oct-2009 17 60266050 100/A-025 CHARAN SINGH 06-Apr-2011 18 60263750 100/A-027 NIRMAL KUMAR LAKHINA 26-Oct-2009 19 60263868 100/A-028 VISHVENDRA CHAUDHARY & AJIT KUMAR 26-Oct-2009 20 60263189 100/A-030 RAJWATI GAUTAM 26-Oct-2009 21 60262994 100/A-033 NANDAN SINGH 26-Dec-2009 22 60263545 100/A-035 S K CHAUHAN,SUSHMA CHAUHAN,VINOD 26-Oct-2009 23 60265570 100/A-036 ANAGPAL 06-Apr-2011 24 60262887 100/A-037 P R DEVELOPERS P LTD DIR VIVEK DIXIT 26-Oct-2009 25 60262241 100/A-038 PRATIMA TANDON 26-Oct-2009 26 60263846 100/A-039 TALON VINIMAY(P) LTD THROUGH DIR.VIKAS 26-Oct-2009 27 60263926 100/A-040 -

Ibps Rrb Officer Scale-I & Office Assistant Capsule 2015

IBPS RRB OFFICER SCALE-I & OFFICE ASSISTANT CAPSULE 2015 Dear Readers, second divides the banks into two categories: scheduled banks Here we are providing you the most awaited capsule which you and non-scheduled banks. In both of these systems of all were demanding for the upcoming banking exams mainly categorization, the Reserve Bank of India, or RBI, is at the center IBPS RRB 2015. of the banking structure. It holds the reserve capital of all In this capsule we have included the Current Affairs, Banking commercial and scheduled banks in the country. Awareness, Static Gk and other sections which are important for Scheduled Banks the upcoming bank exams. The eligibility criteria exist for scheduled banks: Also, in the last we have provided the previous year GK questions a) The first of which entails carrying on the business of banking asked in RRB and other banking exams, so that you all can have in India. an idea about the topics from which the question can be asked. b) All scheduled banks must maintain a reserve capital of 5 lakhs On the basis of last year GK questions, here is the expected rupees in the Reserve Bank of India. pattern for this year RRB. Rememer that the pattern is mainly c) These are registered under the second schedule of RBI Act, from the analysis and it can be changed a bit. 1934. According to our analysis, the break-up of GK portion can be like: S.N Topic of GA No. of questions 1 Banking Awareness 10-15 2 Banking Current Awareness 3-5 3 New Appointments (National/ 2-3 International) 4 National/International Events 3-4 5 Economy/Business News 2 6 Sports 2 7 Awards & Honours 2-3 8 International Orgzn 1 9 Days 1-2 10 Miscellanoeus: Country/Currency, 10 RBI CM/Governors, Head Quarters, Days, 2) RBI AND ITS ROLES Dances, Dams, Power Plants, etc RBI is the central Bank of India and controls the entire the entire 11 Books & Authors 1-2 money issue, circulation and control by its monetary policies and 12 Government Schemes 2 lending policies. -

Annual Report 2010–11 National Council of Applied Economic Research

National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report 2010–11 National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report 2010–11 NCAER | Quality . Relevance . Impact August 2011 Published by Jatinder S. Bedi Secretary and Head, Operations National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate New Delhi 110 002 T +91 11 23379861-3 F +91 11 23370164 W www.ncaer.org E [email protected] Compiled by J.S. Punia ii I NCAER Annual Report 2010–11 About NCAER | Quality . Relevance . Impact he National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) is an T independent policy research institute that supports India’s economic development through empirical economic and sociological research. It is India’s oldest and largest policy think-tank. NCAER was inaugurated by the President of India, Dr Rajendra Prasad, on December 18, 1956. NCAER’s original Governing Body included leading post- Independence figures from both the public and private sectors: John Mathai, C.D. Deshmukh, T.T. Krishnamachari, V.T. Krishnamachari, Ashoka Mehta, J.R.D. Tata, John F. Sinclair, and N.R. Pillai. The Ford Foundation provided much of the initial financial support, including for NCAER’s Sector Management for Europe and Central campus for which Prime Minister Jawaharlal Asia, Governance Adviser, and Lead Nehru laid the foundation stone. The bulk of Economist and Country Coordinator for NCAER’s revenues today come from research Bangladesh. Before joining the World Bank, studies done for the government and the pri- he was the Ford Foundation’s Programme vate sector. This is supplemented by internal Officer for International Economics for resources from NCAER’s endowment income South Asia. -

General Awareness

General Awareness 1. The 4th SAARC culture ministers meeting will be held in which of the following countries? 1) Bangladesh 2) Sri Lanka 3) Nepal 4) Maldives 5) None of these 2. The 1st International Sanskrit Conference was held, recently, in which of the following states? Sanskrit scholars from India and eight foreign countries deliberated on methods to revive the glory of the ancient language. 1) Uttarakhand 2) Madhya Pradesh 3) Gujarat 4) Rajasthan 5) None of these 3. Who among the following has been sworn in as the new Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu? 1) Edappadi K Palaniswami 2) R Vaithilingam 3) Natham R Viswanathan 4) O Panneerselvam 5) None of these 4. The central govt imposed president rule in which of the following states after its chief minister resigned as his party went into minority after its split with its ally recently? 1) Jharkhand 2) Bihar 3) Maharashtra 4) Haryana 5) None of these 5. Who among the following is/was the first chief minister of an Indian state who has been/was convicted and sent to jail during holding the office? 1) Lalu Prasad Yadav 2) J Jayalalithaa 3) Mayawati 4) Mulayam Singh Yadav 5) BS Yeddyurappa 6. PM Narendra Modi promised to merge PIO and OCI schemes to facilitate their hassle-free travel to India. While PIO stands for Persons of Indian Origin, OCI stands for 1) Other Citizenship of India 2) Overseas Countrymen of India 3) Overseas Citizenship of India 4) Other Countrymen of India 5) None of these 7. The prestigious Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize was announced recently. -

Volume Iv: Local Self Governments and Decentralized Governance

D E N C A N S A T N N R E E V M O T N G R E D V CH 2010 E ON ATE RELATIONS O Z I G REPOR L MAR OLUME - IV F A COMMISSION V L R E T S N L E A C CENTRE-ST C E O D L REPORT OF THE COMMISSION ON CENTRE-STATE RELATIONS. MARCH 2010 VOLUME - IV LOCAL SELF GOVERNMENTS AND DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE COMMISSION ON CENTRE-STATE RELATIONS REPORT VOLUME IV LOCAL SELF GOVERNMENTS AND DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE MARCH 2010 THE COMMISSION CHAIRPERSON Shri Justice Madan Mohan Punchhi (Retd.) Former Chief Justice of India MEMBERS Shri Dhirendra Singh Shri Vinod Kumar Duggal Former Secretary to the Former Secretary to the Government of India Government of India Dr. N.R. Madhava Menon Shri Vijay Shanker Former Director, Former Director, National Judicial Academy, Bhopal, and Central Bureau of Investigation, National Law School of India, Bangalore Government of India Dr. Amaresh Bagchi was a Member of the Commission from 04.07.2007 to 20.02.2008, the date he unfortunately passed away. The Commission expresses its deep gratitude to late Dr. Bagchi for his signal contribution during his tenure as a Member. SECRETARIES Shri Amitabha Pande (17.07.2007 - 31.05.2008) Shri Ravi Dhingra (25.06.2008 - 31.03.2009) Shri Mukul Joshi (01.04.2009 - 31.03.2010) i ii The Commission on Centre-State Relations presents its Report to the Government of India. Justice Madan Mohan Punchhi Chairman Dhirendra Singh Vinod Kumar Duggal Member Member Dr. -

Shares to Be Transferred to IEPF

Statement of unclaimed/unpaid dividend (Final Dividend 2012‐13), whose shares being transferred to IEPFAuthority SL NO DPID CLIENTID NAME DIVIDEND AMT SHARES DIVYEAR 1 SRS0000436 TODKAR SHRIKANT SHIVAMURTI 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 2 SRS0000454 VAGGAR MUDAKAPPA BHIMAPPA 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 3 SRS0000597 D COSTA WALLACE WALLY 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 4 SRS0001060 SANIKOPPA MALLIKARJUN BASAPPA 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 5 SRS0001315 HABIB SURESH ANNASA 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 6 SRS0001344 VIJAYKUMAR H A 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 7 SRS0002192 HOTTIGIMATH PARAMESHWAR MAHESHWAR 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 8 SRS0002301 PATTANSHETTI ASHWINIKUMAR VASANTRAO 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 9 SRS0002334 YARAZARVI SHANTANAND BASAVANTAPPA 2500.00 5000 DIV. 2012‐2013 10 SRS0004631 GADI VIRUPAKSHAPPA MALLAPPA 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 11 SRS0006065 DEVANAL VEERASANGAPPA RUDRAPPA 2500.00 5000 DIV. 2012‐2013 12 SRS0006876 HAGIDALE()(SHIDAGOUDA) SURESH BHIMARAO 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 13 SRS0008237 JOSHI NARAYAN KRISHNAJI 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 14 SRS0009530 KULKARNI NITANT SUDHEER 5000.00 10000 DIV. 2012‐2013 15 SRS0011283 PRAKASH M.P 10000.00 20000 DIV. 2012‐2013 16 SRS0051071 SHRIKANT NINGAPPA NEGTINAHAL 320.00 640 DIV. 2012‐2013 17 SRS0065744 CHINTAMANI S KELKAR 200.00 400 DIV. 2012‐2013 18 10601 1201060100194442 HARIDAS PATIL 50.00 100 DIV. 2012‐2013 19 16700 1301670000576141 RAKESH BHUPENDRABHAI JOSHI 50.00 100 DIV. 2012‐2013 20 17502 1201750200053722 NILESH MADANLAL PICHA 25.00 50 DIV. 2012‐2013 21 19101 1201910101014336 J. ANAND PRABHAKAR 25.00 50 DIV. 2012‐2013 22 21900 1302190000094032 MUKUND VASANT KAKADE 75.00 150 DIV. -

Pdf, 197.36 Kb

ISAS Working Paper No. 29 – Date: 2 January 2008 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg India-Myanmar Relations – Geopolitics and Energy in Light of the New Balance of Power in Asia Dr Marie Lall Institute of South Asian Studies1 National University of Singapore and Institute of Education University of London 1 The author would like to thank the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore, for funding the fieldwork over six weeks in India and Myanmar for this research report. Dr Lall was a Visiting Research Fellow at ISAS from April to August 2007. She can be reached at [email protected]. Executive Summary of Research Findings In light of India’s changing foreign policy over the last decade, Indo-Myanmar relations have also changed radically. The reasons thereof pertain principally to four factors: the economic development of India’s North East, India’s increased interest in trade with ASEAN, India’s search for energy security and increased Chinese involvement in Myanmar. This paper offers an in depth analysis of these issues, drawing on seven weeks of fieldwork during the summer of 2007 and over 50 interviews with officials and academics in both countries. The summary of the fieldwork is listed below. The paper concludes that, although today Indo-Myanmar relations have improved, India has, in essence, been too slow to develop this important relationship and is now loosing out to China. -

1. Report of the Technical Expert

September SECRET 2010 Report of the Technical Expert on The Implementation of the Steps Flowing from the Political, Constitutional, Judicial and Administrative Events that took place between 1947 and 2010, in the area of Reservation in Public Employment for the People of the Telangana Region in the State of Andhra Pradesh Mukesh Kacker (IAS) Report of the Technical Expert on The Implementation of the Steps Flowing from the Political, Constitutional, Judicial and Administrative Events that took place between 1947 and 2010, in the area of Reservation in Public Employment for the People of the Telangana Region in the State of Andhra Pradesh Presented to The Committee for Consultation on the Situation in Andhra Pradesh 2 | Page Foreword It was indeed a unique opportunity to write the factual history of a particular period and also attempt an analytical critique of that history at the same time. This process required the play of two different faculties of mind and two different approaches. While the recording of events in their correct chronological sequence is a function of research and diligence, writing an analytical critique of those events requires perspective and the capacity to present the big picture, to separate the grain from the chaff. This was essential as the history of the issue of reservation on the basis of residential qualification in the Telangana region is replete with political agreements and formulae, constitutional provisions, legislative enactments, judicial orders, reports of Commissions and hundreds of government orders and instructions. It is easy to lose sight of the woods in the maze of these trees. -

Bankersadda August (1-31) Q1

Page 1 of 134 BANKERSADDA AUGUST (1-31) Q1. Name the australian all-rounder who have became the first cricketer to reach the milestone of scoring 1000 runs and taking 100 wickets in the T20 format. Ellyse Perry Rachael Haynes Nicole Bolton Shane watson Glenn Maxwell Solution: Australia all-rounder Ellyse Perry became the first cricketer of either gender to reach the rare milestone of scoring 1000 runs and taking 100 wickets in the T20 format. Q2. Name the West African country to which India extended the assistance of USD 500,000 to support the skill development and cottage industry projects in the country. Cape Verde Benin Burkina Faso Gambia Ghana Solution: India will extend the assistance of USD 500,000 to the West African country "Gambia" to support the skill development and cottage industry projects in the country. Q3. Who has been given the additional charge of the post of Director General Narcotics Control Bureau by the Appointments Committee of Cabinet? P C Mody Rajiv Rai Bhatnagar Arvind Kumar Anil Kumar Dhasmana Rakesh Asthana Solution: For more join - https://t.me/bhawna_weekly_quiz_pdf https://t.me/reasoning_group https://t.me/quant_group https://t.me/adda4ssc https://t.me/adda4english https://t.me/ca_quizzes https://t.me/target_mains_puzzles Page 2 of 134 The Appointments Committee on Cabinet has given the additional charge of the post of Director General Narcotics Control Bureau to Rakesh Asthana. Q4. Name the Indian Air Force Wing Commander who has become the first Indian Air Force pilot to perform a wingsuit skydive jump. A Sudharsanan Bhopali Biswas Tarun Chaudhri V Anthem A Dhawade Solution: Wing Commander Tarun Chaudhri has become the first Indian Air Force pilot to perform a wingsuit skydive jump. -

Volume V: Internal Security, Criminal Justice and Centre-State Co-Operation

L N A O N I I T M A I R R E C D , P Y N O T T A O I C R E C U E CH 2010 ON I ATE RELATIONS C T T E A S REPOR OLUME - V S T MAR U V S COMMISSION J L - A E N R R T E N CENTRE-ST T E N C I REPORT OF THE COMMISSION ON CENTRE-STATE RELATIONS. MARCH 2010 VOLUME - V INTERNAL SECURITY, CRIMINAL JUSTICE AND CENTRE-STATE COOPERATION COMMISSION ON CENTRE-STATE RELATIONS REPORT VOLUME V INTERNAL SECURITY, CRIMINAL JUSTICE AND CENTRE-STATE CO-OPERATION MARCH 2010 THE COMMISSION CHAIRPERSON Shri Justice Madan Mohan Punchhi (Retd.) Former Chief Justice of India MEMBERS Shri Dhirendra Singh Shri Vinod Kumar Duggal Former Secretary to the Former Secretary to the Government of India Government of India Dr. N.R. Madhava Menon Shri Vijay Shanker Former Director, Former Director, National Judicial Academy, Bhopal, and Central Bureau of Investigation, National Law School of India, Bangalore Government of India Dr. Amaresh Bagchi was a Member of the Commission from 04.07.2007 to 20.02.2008, the date he unfortunately passed away. The Commission expresses its deep gratitude to late Dr. Bagchi for his signal contribution during his tenure as a Member. SECRETARIES Shri Amitabha Pande (17.07.2007 - 31.05.2008) Shri Ravi Dhingra (25.06.2008 - 31.03.2009) Shri Mukul Joshi (01.04.2009 - 31.03.2010) The Commission on Centre-State Relations presents its Report to the Government of India.