Psychoanalysis and the Bloomsbury Group 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It Is Time for Virginia Woolf

TREBALL DE FI DE GRAU Tutor/a: Dra. Ana Moya Gutierrez Grau de: Estudis Anglesos IT IS TIME FOR VIRGINIA WOOLF Ane Iñigo Barricarte Universitat de Barcelona Curso 2018/2019, G2 Barclona, 11 June 2019 ABSTRACT This paper explores the issue of time in two of Virginia Woolf’s novels; Mrs Dalloway and To the Lighthouse. The study will not only consider how the theme is presented in the novels but also in their filmic adaptations, including The Hours, a novel written by Michael Cunningham and film directed by Stephen Daldry. Time covers several different dimensions visible in both novels; physical, mental, historical, biological, etc., which will be more or less relevant in each of the novels and which, simultaneously, serve as a central point to many other themes such as gender, identity or death, among others. The aim of this paper, beyond the exploration of these dimensions and the connection with other themes, is to come to a general and comparative conclusion about time in Virginia Woolf. Key Words: Virginia Woolf, time, adaptations, subjective, objective. Este trabajo consiste en una exploración del tema del tiempo en dos de las novelas de Virginia Woolf; La Señora Dalloway y Al Faro. Dicho estudio, no solo tendrá en cuenta como se presenta el tema en las novelas, sino también en la adaptación cinematográfica de cada una de ellas, teniendo también en cuenta Las Horas, novela escrita por Michael Cunningham y película dirigida por Stephen Daldry. El tiempo posee diversas dimensiones visibles en ambos trabajos; física, mental, histórica, biológica, etc., que cobrarán mayor o menor importancia en cada una de las novelas y que, a su vez, sirven de puntos de unión para otros muchos temas como pueden ser el género, la identidad o la muerte entre otros. -

AWAR of INDIVIDUALS: Bloomsbury Attitudes to the Great

2 Bloomsbury What were the anti-war feelings chiefly expressed outside ‘organised’ protest and not under political or religious banners – those attitudes which form the raison d’être for this study? As the Great War becomes more distant in time, certain actions and individuals become greyer and more obscure whilst others seem to become clearer and imbued with a dash of colour amid the sepia. One thinks particularly of the so-called Bloomsbury Group.1 Any overview of ‘alter- native’ attitudes to the war must consider the responses of Bloomsbury to the shadows of doubt and uncertainty thrown across page and canvas by the con- flict. Despite their notoriety, the reactions of the Bloomsbury individuals are important both in their own right and as a mirror to the similar reactions of obscurer individuals from differing circumstances and backgrounds. In the origins of Bloomsbury – well known as one of the foremost cultural groups of the late Victorian and Edwardian periods – is to be found the moral and aesthetic core for some of the most significant humanistic reactions to the war. The small circle of Cambridge undergraduates whose mutual appreciation of the thoughts and teachings of the academic and philosopher G.E. Moore led them to form lasting friendships, became the kernel of what would become labelled ‘the Bloomsbury Group’. It was, as one academic described, ‘a nucleus from which civilisation has spread outwards’.2 This rippling effect, though tem- porarily dammed by the keenly-felt constrictions of the war, would continue to flow outwards through the twentieth century, inspiring, as is well known, much analysis and interpretation along the way. -

EM Forster's Howards End and Virginia Woolfs Mrs. Dalloway

The Metropolis and the Oceanic Metaphor: E.M. Forster's Howards End and Virginia Woolfs Mrs. Dalloway Melissa Baty UH 450 / Fall 2003 Advisor: Dr. Jon Hegglund Department of English Honors Thesis ************************* PASS WITH DISTINCTION Thesis Advisor Signature Page 1 of 1 TO THE UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE: As thesis advisor for Me~~'Y3 ~3 I have read this paper and find it satisfactory. 1 1-Z2.-03 Date " http://www.wsu.edu/~honors/thesis/AdvisecSignature.htm 9/22/2003 Precis Statement ofResearch Problem: In the novels Howards End by E.M. Forster and Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, the two authors illwninate their portrayal ofearly twentieth-century London and its rising modernity with oceanic metaphors. My research in history, cultural studies, literary criticism, and psychoanalytic theory aimed to discover why and to what end Forster and Woolf would choose this particular image for the metropolis itselfand for social interactions within it. Context of the Problem: My interpretation of the oceanic metaphor in the novels stems from the views of particular theorists and writers in urban psychology and sociology (Anthony Vidler, Georg Simmel, Jack London) and in psychoanalysis (Sigmund Freud, particularly in his correspondence with writer Romain Rolland). These scholars provide descriptions ofthe oceanic in varying manners, yet reflect the overall trend in the period to characterizing life experience, and particularly experiences in the city, through images and metaphors ofthe sea. Methods and Procedures: The research for this project entailed reading a wide range ofhistorically-specific background regatg ¥9fSter, W661f~ eity of I .Q~e various academic areas listed above in order to frame my conclusions about the novels appropriately. -

Bloomsbury Scientists Ii Iii

i Bloomsbury Scientists ii iii Bloomsbury Scientists Science and Art in the Wake of Darwin Michael Boulter iv First published in 2017 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ ucl- press Text © Michael Boulter, 2017 Images courtesy of Michael Boulter, 2017 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Michael Boulter, Bloomsbury Scientists. London, UCL Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350045 Further details about Creative Commons licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 006- 9 (hbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 005- 2 (pbk) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 004- 5 (PDF) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 007- 6 (epub) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 008- 3 (mobi) ISBN: 978- 1- 78735- 009- 0 (html) DOI: https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787350045 v In memory of W. G. Chaloner FRS, 1928– 2016, lecturer in palaeobotany at UCL, 1956– 72 vi vii Acknowledgements My old writing style was strongly controlled by the measured precision of my scientific discipline, evolutionary biology. It was a habit that I tried to break while working on this project, with its speculations and opinions, let alone dubious data. But my old practices of scientific rigour intentionally stopped personalities and feeling showing through. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Fast Horses The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 - 1920 Harper, Esther Fiona Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 Fast Horses: The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 – 1920 Esther Harper Ph.D. History King’s College London April 2018 1 2 Abstract Sports historians have identified the 19th century as a period of significant change in the sport of horseracing, during which it evolved from a sporting pastime of the landed gentry into an industry, and came under increased regulatory control from the Jockey Club. -

The Tyro a Review of the Arts of Painting Sculptore and Design

THE TYRO A REVIEW OF THE ARTS OF PAINTING SCULPTORE AND DESIGN. EDITED BY WYNDHAM LEWIS. TO BE PRODUCED AT INTERVALS OF TWO OR THREE MONTHS. Publishers : THE EGOIST PRESS, 2, ROBERT STREET, ADELPH1. PUBLISHED AT 1s. 6d, Subscription for 4 numbers, 6s. 6d, with postage. Printed by Bradley & Son, Ltd., Little Crown Yard, Mill Lane, Reading. NOTE ON TYROS. We present to you in this number the pictures of several very powerful Tyros.* These immense novices brandish their appetites in their faces, lay bare their teeth in a valedictory, inviting, or merely substantial laugh. A. laugh, like a sneeze, exposes the nature of the individual with an unexpectedness that is perhaps a little unreal. This sunny commotion in the face, at the gate of the organism, brings to the surface all the burrowing and interior broods which the individual may harbour. Understanding this so well, people hatch all their villainies in this seductive glow. Some of these Tyros are trying to furnish you with a moment of almost Mediterranean sultriness, in order, in this region of engaging warmth, to obtain some advantage over you. But most of them are, by the skill of the artist, seen basking themselves in the sunshine of their own abominable nature. These partly religious explosions of laughing Elementals are at once satires, pictures, and stories The action of a Tyro is necessarily very restricted; about that of a puppet worked with deft fingers, with a screaming voice underneath. There is none" of the pathos of Pagliacci in the story of the Tyro. It is the child in him that has risen in his laugh, and you get a perspective of his history. -

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 Through 2009

Works on Giambattista Vico in English from 1884 through 2009 COMPILED BY MOLLY BLA C K VERENE TABLE OF CON T EN T S PART I. Books A. Monographs . .84 B. Collected Volumes . 98 C. Dissertations and Theses . 111 D. Journals......................................116 PART II. Essays A. Articles, Chapters, et cetera . 120 B. Entries in Reference Works . 177 C. Reviews and Abstracts of Works in Other Languages ..180 PART III. Translations A. English Translations ............................186 B. Reviews of Translations in Other Languages.........192 PART IV. Citations...................................195 APPENDIX. Bibliographies . .302 83 84 NEW VICO STUDIE S 27 (2009) PART I. BOOKS A. Monographs Adams, Henry Packwood. The Life and Writings of Giambattista Vico. London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reprinted New York: Russell and Russell, 1970. REV I EWS : Gianturco, Elio. Italica 13 (1936): 132. Jessop, T. E. Philosophy 11 (1936): 216–18. Albano, Maeve Edith. Vico and Providence. Emory Vico Studies no. 1. Series ed. D. P. Verene. New York: Peter Lang, 1986. REV I EWS : Daniel, Stephen H. The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography, n.s. 12 (1986): 148–49. Munzel, G. F. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 173–75. Simon, L. Canadian Philosophical Reviews 8 (1988): 335–37. Avis, Paul. The Foundations of Modern Historical Thought: From Machiavelli to Vico. Beckenham (London): Croom Helm, 1986. REV I EWS : Goldie, M. History 72 (1987): 84–85. Haddock, Bruce A. New Vico Studies 5 (1987): 185–86. Bedani, Gino L. C. Vico Revisited: Orthodoxy, Naturalism and Science in the ‘Scienza nuova.’ Oxford: Berg, 1989. REV I EWS : Costa, Gustavo. New Vico Studies 8 (1990): 90–92. -

Undergraduate Prospectus 2021 Entry

Undergraduate 2021 Entry Prospectus Image captions p15 p30–31 p44 p56–57 – The Marmor Homericum, located in the – Bornean orangutan. Courtesy of USO – UCL alumnus, Christopher Nolan. Courtesy – Students collecting beetles to quantify – Students create a bespoke programme South Cloisters of the Wilkins Building, depicts Homer reciting the Iliad to the – Saltburn Mine water treatment scheme. of Kirsten Holst their dispersion on a beach at Atlanterra, incorporating both arts and science and credits accompaniment of a lyre. Courtesy Courtesy of Onya McCausland – Recent graduates celebrating at their Spain with a European mantis, Mantis subjects. Courtesy of Mat Wright religiosa, in the foreground. Courtesy of Mat Wright – Community mappers holding the drone that graduation ceremony. Courtesy of John – There are a number of study spaces of UCL Life Sciences Front cover captured the point clouds and aerial images Moloney Photography on campus, including the JBS Haldane p71 – Students in a UCL laboratory. Study Hub. Courtesy of Mat Wright – UCL Portico. Courtesy of Matt Clayton of their settlements on the peripheral slopes – Students in a Hungarian language class p32–33 Courtesy of Mat Wright of José Carlos Mariátegui in Lima, Peru. – The Arts and Sciences Common Room – one of ten languages taught by the UCL Inside front cover Courtesy of Rita Lambert – Our Student Ambassador team help out in Malet Place. The mural on the wall is p45 School of Slavonic and East European at events like Open Days and Graduation. a commissioned illustration for the UCL St Paul’s River – Aerial photograph showing UCL’s location – Prosthetic hand. Courtesy of UCL Studies. -

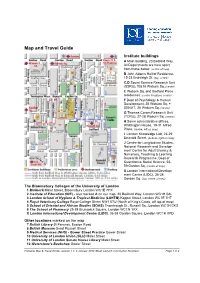

Map and Travel Guide

Map and Travel Guide Institute buildings A Main building, 20 Bedford Way. All Departments are here apart from those below. (centre of map) B John Adams Hall of Residence, 15-23 Endsleigh St. (top, centre) C,D Social Science Research Unit (SSRU),10&18 Woburn Sq. (centre) E Woburn Sq. and Bedford Place residences. (centre & bottom, centre) F Dept of Psychology & Human Development, 25 Woburn Sq. + SENJIT, 26 Woburn Sq. (centre) G Thomas Coram Research Unit (TCRU), 27-28 Woburn Sq. (centre) H Some administrative offices, Whittington House, 19-31 Alfred Place. (centre, left on map) I London Knowledge Lab, 23-29 Emerald Street. (bottom, right on map) J Centre for Longitudinal Studies, National Research and Develop- ment Centre for Adult Literacy & Numeracy, Teaching & Learning Research Programme, Dept of Quantitative Social Science, 55- 59 Gordon Sq. (centre of map) X London International Develop- ment Centre (LIDC), 36-38 (top, centre of map) Gordon Sq. The Bloomsbury Colleges of the University of London 1 Birkbeck Malet Street, Bloomsbury London WC1E 7HX 2 Institute of Education (IOE) - also marked A on our map, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL 3 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT 4 Royal Veterinary College Royal College Street NW1 0TU (North of King's Cross, off top of map) 5 School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Thornhaugh St., Russell Sq., London WC1H 0XG 6 The School of Pharmacy 29-39 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AX X London International Development Centre (LIDC), 36-38 Gordon -

On Ambivalence

PROBLEMI INTERNATIONAL, vol.On 1 no.Ambivalence 1, 2017 © Society for Theoretical Psychoanalysis On Ambivalence Tadej Troha The term “ambivalence” was coined a little over hundred years ago by Eugen Bleuler, the then director of Burghölzli, who despite sympathizing with psychoanalysis refrained from becoming a genuine part of the emerging Freudian collective body. In the end, his insistence on maintaining his individuality produced an ironic twist: while Freud (and Jung, for that matter) became popular authors, Bleuler was left with the impossible trophy of being the author of popular signifiers, the author of terms that seem to have appeared out of nowhere: in addition to ambivalence, he ought to be credited for inventing “autism” and “schizophrenia.” It is well known that Freud was not very enthusiastic about the latter terms and kept insisting on paraphrenia and narcissism, respectively. As for ambivalence, he accepted it immediately and without hesitation. When introduced in Freud’s essays, ambiva- lence is accompanied with a whole series of laudatory remarks: the term is glücklich, gut, passend, trefflich, “happily chosen” (Freud 2001 [1905], p. 199), “excellent” (Freud 2001 [1912], p. 106), “appropriate” (Freud 2001 [1909], p. 239n), “very apt” (Freud 2001 [1915], p. 131). Although he rarely fails to point out that he is not the author of the term, he never bothers to present the reader with the particular clinical framework within which the term has been invented. The praise of the author is here transformed into the praise of the term itself, the quotation does not add anything to Bleuler’s authority; it is rather an excuse to repeatedly point to the authority and breakthrough nature of the 217 Tadej Troha very conceptual background that made the invention possible. -

Novel to Novel to Film: from Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway to Michael

Rogers 1 Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ Novel to Novel to Film: From Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway to Michael Cunningham’s and Daldry-Hare’s The Hours Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Literature at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Fall 2015 By Jacob Rogers ____________________ Thesis Director Dr. Kirk Boyle ____________________ Thesis Advisor Dr. Lorena Russell Rogers 2 All the famous novels of the world, with their well known characters, and their famous scenes, only asked, it seemed, to be put on the films. What could be easier and simpler? The cinema fell upon its prey with immense rapacity, and to this moment largely subsists upon the body of its unfortunate victim. But the results are disastrous to both. The alliance is unnatural. Eye and brain are torn asunder ruthlessly as they try vainly to work in couples. (Woolf, “The Movies and Reality”) Although adaptation’s detractors argue that “all the directorial Scheherezades of the world cannot add up to one Dostoevsky, it does seem to be more or less acceptable to adapt Romeo and Juliet into a respected high art form, like an opera or a ballet, but not to make it into a movie. If an adaptation is perceived as ‘lowering’ a story (according to some imagined hierarchy of medium or genre), response is likely to be negative...An adaptation is a derivation that is not derivative—a work that is second without being secondary. -

John Halperin Bloomsbury and Virginia W

John Halperin ., I Bloomsbury and Virginia WooH: Another VIew . i· "It had seemed to me ever since I was very young," Adrian Stephen wrote in The Dreadnought Hoax in 1936, "that anyone who took up an attitude of authority over anyone else was necessarily also someone who offered a leg to pull." 1 In 1910 Adrian and his sister Virginia and Duncan Grant and some of their friends dressed up as the Emperor of Abyssinia and his suite and perpetrated a hoax upon the Royal Navy. They wished to inspect the Navy's most modern vessel, they said; and the Naval officers on hand, completely fooled, took them on an elaborate tour of some top secret facilities aboard the HMS Dreadnought. When the "Dread nought Hoax," as it came to be called, was discovered, there were furious denunciations of the group in the press and even within the family, since some Stephen relations were Naval officers. One of them wrote to Adrian: "His Majesty's ships are not suitable objects for practical jokes." Adrian replied: "If everyone shared my feelings toward the great armed forces of the world, the world [might] be a happier place to live in . .. armies and suchlike bodies [present] legs that [are] almost irresistible." Earlier a similarly sartorial practical joke had been perpetrated by the same group upon the mayor of Cam bridge, but since he was a grocer rather than a Naval officer the Stephen family seemed unperturbed by this-which was not really a thumbing·of-the-nose at the Establishment. The Dreadnought Hoax was harder to forget.