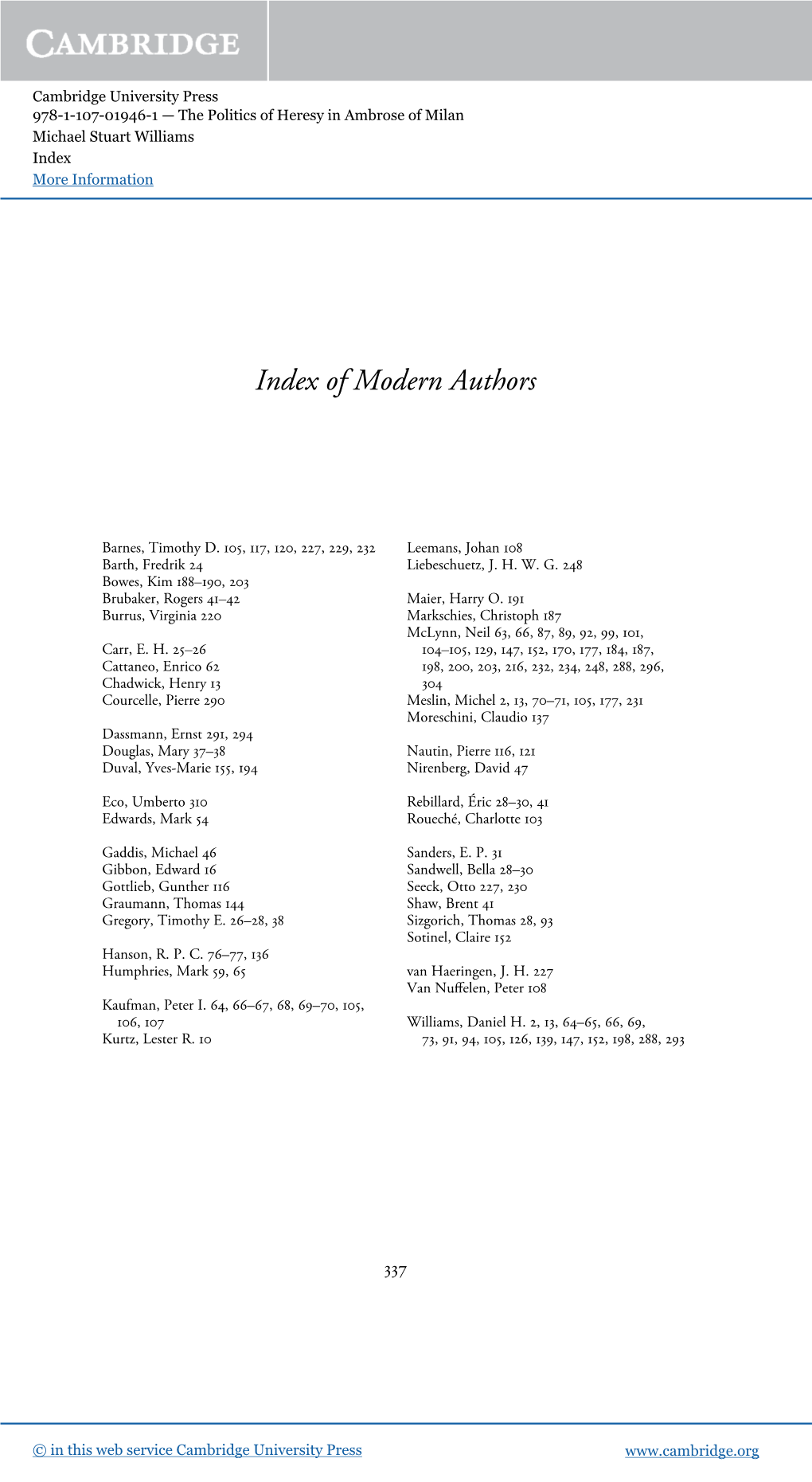

Index of Modern Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman-Barbarian Marriages in the Late Empire R.C

ROMAN-BARBARIAN MARRIAGES IN THE LATE EMPIRE R.C. Blockley In 1964 Rosario Soraci published a study of conubia between Romans and Germans from the fourth to the sixth century A.D.1 Although the title of the work might suggest that its concern was to be with such marriages through- out the period, in fact its aim was much more restricted. Beginning with a law issued by Valentinian I in 370 or 373 to the magister equitum Theodosius (C.Th. 3.14.1), which banned on pain of death all marriages between Roman pro- vincials and barbarae or gentiles, Soraci, after assessing the context and intent of the law, proceeded to discuss its influence upon the practices of the Germanic kingdoms which succeeded the Roman Empire in the West. The text of the law reads: Nulli provineialium, cuiuscumque ordinis aut loci fuerit, cum bar- bara sit uxore coniugium, nec ulli gentilium provinciales femina copuletur. Quod si quae inter provinciales atque gentiles adfinitates ex huiusmodi nuptiis extiterit, quod in his suspectum vel noxium detegitur, capitaliter expietur. This was regarded by Soraci not as a general banning law but rather as a lim- ited attempt, in the context of current hostilities with the Alamanni, to keep those barbarians serving the Empire (gentiles)isolated from the general Roman 2 populace. The German lawmakers, however, exemplified by Alaric in his 63 64 interpretatio,3 took it as a general banning law and applied it in this spir- it, so that it became the basis for the prohibition under the Germanic king- doms of intermarriage between Romans and Germans. -

Cemetery Info by Death

Birth Death Sister Former Last Name Month Day Year Month Day Year SEC Row NO Claudia Pehura January 1 1881 B1 19 2 Clara Seiter August 17 1837 April 24 1881 B1 20 1 Maria Spitznagel January 31 1882 B1 15 1 Borgia Muelhaupt July 12 1882 B1 19 1 Constantia Stocker June 1 1882 B2 3 4 Ursula Kremer November 1 1882 B1 18 3 Dominica Braxmeier November 1 1883 B1 24 3 Theodora Unknown October 1 1883 B1 24 2 Armella Schuehle March 3 1884 B1 18 2 Catherina Schuele March 11 1884 B1 21 1 Adelheid Riesterer May 3 1886 B1 23 3 Albertina (Ms) (Train wreck) Schmitt October 28 1886 B1 17 4 Dionysia (Train wreck) Schwab October 28 1886 B1 16 3 Juliana Unknown 1885 January 1 1888 B1 23 2 Constantia Foehrenbach June 30 1888 B1 21 2 Veronica Eberle August 16 1890 B1 20 2 Dorothea Dresel April 4 1891 B1 20 3 Eugenia Kalt April 25 1891 B1 16 8 Susanna Gersbach August 14 1891 B1 16 9 Constantia Schildgen December 11 1892 B1 16 10 Fridolina Hoefler April 23 1893 B1 15 3 (d) Agatha Bisch (on stone 1894 May 10 1893 B1 15 5 Dionysia Schermann March 28 1894 B1 15 4 Clara On stone Renz April 4 1985 April 3 1895 B1 15 6 Frumentia Dudinger July 24 1895 B2 4 1 Thomasine Hickey June 2 1895 B1 14 7 Natalia Breitweiser April 24 1896 B2 4 4 Lydia Kuehle August 6 1896 B2 3 3 Anna Weis August 14 1896 B2 4 3 Josephina Maloney May 10 1896 B2 3 2 Helena Williams August 14 1897 B1 14 10 Maria Pehura July 20 1897 B1 14 8 Leocadia Jagemann March 26 1898 B2 2 1 Nicodema Lomele March 25 1899 B2 2 2 Adela Mayer April 7 1900 B2 2 3 Scholastica Philipp August 27 1900 B2 1 3 Nepomucka -

History Unveiling Prophecy (Or Time As an Interpreter)

1906 Digitally formatted for Historicism.com in 2003 courtesy of B. Keenan. "Reading The Approaching End of the Age was somewhat of a turning point in my belief in the bible. It is a very convincing argument that the bible is influenced by some supernatural power. It has given me a strong enthusiasm for learning more of what H. Grattan Guinness has to say, along with many other authors that cover end time (current) events, and the plethora of fabricated events in history leading to this stage." – B. Keenan For more information on Henry Grattan Guinness, and a list of his works that are available on the Internet, visit the H. Grattan Guinness Archive at http://www.historicism.com/Guinness. © 2003 Historicism.com PREFACE THE lofty decree of Papal Infallibility issued by the Vatican Council of 1870, immediately followed by the sudden and final fall of the Papal Temporal Power, after a duration of more than a thousand years, was the primary occasion of my writing that series of works on the fulfilment of Scripture prophecy which has appeared during the last quarter of a century. I left Paris, where I had been labouring in the Gospel, at the outbreak of the Franco-German war in July, 1870. It was in the light of the German bombardment of that city, of the ring of fire which surrounded it, and of the burning of the Tuileries, that I began to read with interest and understanding the prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse. Subsequent visits to Italy and Rome enlarged my view of the subject. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Meletian schism at antioch Barker, Celia B. How to cite: Barker, Celia B. (1974) The Meletian schism at antioch, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9969/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE MSLETIAN SCHISM AT ANTIOCH THE MELETIAN SCHISM AT ANTIOCH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM BY CELIA B. BARKER, B.A. (Dunelm) FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Department of Theology, Date: April,1974. University of Durham. (1) The object of this thesis is to examine the schism in the Church of Antioch during the Arian Controversy of the Fourth century, with a view to establishing what coherent order, if any, can be found in the course of events, and to show how the interaction of theological emphases and personal prejudices exacerbated and prolonged the Antiochene divisions. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Could a Heretic Be a Beautiful Woman in Socrates of Constantinople's and Sozomenus's Eyes?

REVIEW OF HISTORICAL SCIENCES 2017, VOL. XVI, NO. 3 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1644-857X.16.03.08 MINOR WORKS AND MATERIALS Sławomir BralewSki UniverSity of lodz* Could a heretic be a beautiful woman in Socrates of Constantinople’s and Sozomenus’s eyes? their Historia Ecclesiastica Socrates of Constantinople and Hermias Sozomenus mention women of various mar- In ital and social status. We know some of their names, oth- ers are anonymous and we can only learn that they were wives, daughters, widows or virgins. Either way, they appear in the back- ground of the historians’ narrations about the history of the Church as well as records of political events. Of all women, both Socrates and Sozomenus devoted most attention to empresses. Among them there was an exceptionally beautiful woman: Empress Justina, the wife of Valentinian I, who was, however, a follower of Arianism, so in Socrates’s and Sozomenus’s eyes she was a heretic; but can a heretic be beautiful? How was Justina presented by the afore- mentioned church historians? Did Socrates and Sozomenus, who, to a big extent, based his Historia Ecclesiastica on the Socrates’s work1, really perceive that empress similarly. Did he intentionally * The Faculty of Philosophy and History, The Institute of History, The Depart- ment of Byzantine History / Wydział Filozoficzno-Historyczny, Instytut Historii, Katedra Historii Bizancjum, e-mail: [email protected]. 1 The relation between Sozomenus’s and Socrates’s texts has been pointed out several times. See G.C. H a n s e n, Einleintung, [in:] Sozomenus, Kirchengeschichte, eds I. -

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus

The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus ‘A thesis submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy’ 2016 Jillian Mitchell For Michael – and in memory of my father Kenneth who started it all Abstract for PhD Thesis in Classics The Religious World of Quintus Aurelius Symmachus This thesis explores the last decades of legal paganism in the Roman Empire of the second half of the fourth century CE through the eyes of Symmachus, orator, senator and one of the most prominent of the pagans of this period living in Rome. It is a religious biography of Symmachus himself, but it also considers him as a representative of the group of aristocratic pagans who still adhered to the traditional cults of Rome at a time when the influence of Christianity was becoming ever stronger, the court was firmly Christian and the aristocracy was converting in increasingly greater numbers. Symmachus, though long known as a representative of this group, has only very recently been investigated thoroughly. Traditionally he was regarded as a follower of the ancient cults only for show rather than because of genuine religious beliefs. I challenge this view and attempt in the thesis to establish what were his religious feelings. Symmachus has left us a tremendous primary resource of over nine hundred of his personal and official letters, most of which have never been translated into English. These letters are the core material for my work. I have translated into English some of his letters for the first time. -

CHURCH HISTORY LITERACY Lesson 24 St

CHURCH HISTORY LITERACY Lesson 24 St. Ambrose Takes His Stand Before we leave the 300’s, we need to spend some time discussing St. Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan.1 Ambrose fits into the time period of our last class, active both before and after the Council of Constantinople, which finally placed Arianism2 into the category of heresy. Ambrose famously took stands based on his faith that could easily have cost him his position, if not his life. I have asked Edward to: (i) discuss Ambrose, (ii) discuss these key life events, and (iii) use some personal examples from his life along with scripture in order to put a contemporary understanding of lessons we might learn and inspirations we might find from our examination of St. Ambrose. BACKGROUND Ambrose was born around 3393 in Treves (modern Trier, Germany). He lived about 58 years, dying April 4, 397. His family was of Roman nobility, his father being “Praetorian Prefect” of the Gauls, a high position of authority. Ambrose had one brother and one sister. While Ambrose was still a young boy, his father died. Ambrose and his siblings were then brought to Rome. In Rome, Ambrose received an excellent education in both law and the broader liberal arts. Latin was the common language for Ambrose, but he was also well trained in Greek both at home and at school. There is some indication that Ambrose’s family was originally of Greek origin. 1 More so than normal, in preparation of this lesson, I am indebted to the New Catholic Encyclopedia, Second Edition. -

Collected Orations of Pope Pius II. Edited and Translated by Michael Von Cotta-Schönberg

Collected Orations of Pope Pius II. Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg. Vol. 2: Orations 1-5 (1436-1445). 8th version Michael Cotta-Schønberg To cite this version: Michael Cotta-Schønberg. Collected Orations of Pope Pius II. Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg. Vol. 2: Orations 1-5 (1436-1445). 8th version. Scholars’ Press. 2019, 9786138910725. hal-01276919 HAL Id: hal-01276919 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01276919 Submitted on 24 Aug 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Collected orations of Pope Pius II. Vol. 2 0 Collected orations of Pope Pius II. Edited and translated by Michael von Cotta-Schönberg Vol. 2: Orations 1-5 (1436-1445) Preliminary edition, 8th version 2019 1 Abstract Volume 2 of the Collected Orations of Pope Pius II contains four orations and one sermon held in the period from 1436 to 1443. The first three orations and the sermon are from his time at the Council of Basel and the fourth oration from his time at the Imperial Chancery of Emperor Friedrich III. Keywords Enea Silvio Piccolomini; Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini; Aenas Sylvius Piccolomini; Pope Pius II; Papa Pio II; Renaissance orations; Renaissance oratory; Renaissance rhetorics; 1436-1443; 15th century; Church History; Council of Basel; Council of Basle; See of Freising; Freisinger Bistumsstreit Editor and translator Michael v. -

To the People of Antioch and the Bishops of Africa

A SELECT LIBRARY OF THE NICENE AND POST-NICENE FATHERS OF THE CHRISTIAN CHURCH. SECOND SERIES TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH WITH PROLEGOMENA AND EXPLANATORY NOTES. VOLUMES I–VII. UNDER THE EDITORIAL SUPERVISION OF PHILIP SCHAFF, D.D., LL.D., PROFESSOR OF CHURCH HISTORY IN THE UNION THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, NEW YORK. AND HENRY WACE, D.D., PRINCIPAL OF KING’S COLLEGE, LONDON. VOLUME IV ATHANASIUS: TO THE PEOPLE OF ANTIOCH AND TO THE BISHOPS OF AFRICA T&T CLARK EDINBURGH __________________________________________________ WM. B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN 481 Introduction to Tomus Ad Antiochenos. ———————————— THE word ‘tome’ (τόμος) means either a section, or, in the case of such a document as that before us, a concise statement. It is commonly applied to synodical letters (cf. the ‘Tome’ of Leo, A.D. 450, to Flavian). Upon the accession of Julian (November, 361) the Homœan ascendancy which had marked the last six years of Constantius collapsed. A few weeks after his accession (Feb. 362) an edict recalled all the exiled Bishops. On Feb. 21 Athanasius re-appeared in Alexandria. He was joined there by Lucifer of Cagliari and Eusebius of Vercellæ, who were in exile in Upper Egypt. Once more free, he took up the work of peace which had busied him in the last years of his exile (see Prolegg. ch. ii. §9). With a heathen once more on the throne of the Cæsars, there was everything to sober Christian party spirit, and to promise success to the council which met under Athanasius during the ensuing summer. Among the twenty-one bishops who formed the assembly the most notable are Eusebius of Vercellæ, Asterius of Petra, and Dracontius of Lesser Hermopolis and Adelphius of Onuphis, the friends and correspondents of Athanasius. -

Virginity Discourse and Ascetic Politics in the Writings of Ambrose of Milan

Virginity Discourse and Ascetic Politics in the Writings of Ambrose of Milan by Ariel Bybee Laughton Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Dr. Elizabeth A. Clark, Supervisor ___________________________ Dr. Lucas Van Rompay ___________________________ Dr. J. Warren Smith ___________________________ Dr. J. Clare Woods ___________________________ Dr. Zlatko Pleše Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Virginity Discourse and Ascetic Politics in the Writings of Ambrose of Milan by Ariel Bybee Laughton Department of Religion Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Dr. Elizabeth A. Clark, Supervisor ___________________________ Dr. Lucas Van Rompay ___________________________ Dr. J. Warren Smith ___________________________ Dr. J. Clare Woods ___________________________ Dr. Zlatko Pleše An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religion in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Ariel Bybee Laughton 2010 ABSTRACT Ambrose, bishop of Milan, was one of the most outspoken advocates of Christian female virginity in the fourth century C.E. This dissertation examines his writings on virginity in the interest of illuminating the historical and social contexts of his teachings. Considering Ambrose’s treatises on virginity as literary productions with social, political, and theological functions in Milanese society, I look at the various ways in which the bishop of Milan formulated ascetic discourse in response to the needs and expectations of his audience. Furthermore, I attend to the various discontinuities in Ambrose’s ascetic writings in the hope of illuminating what kinds of ideological work these texts were intended to perform by the bishop within Milanese society and beyond.