American Immigrant Writers and the New Global Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joe Rosochacki - Poems

Poetry Series Joe Rosochacki - poems - Publication Date: 2015 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Joe Rosochacki(April 8,1954) Although I am a musician, (BM in guitar performance & MA in Music Theory- literature, Eastern Michigan University) guitarist-composer- teacher, I often dabbled with lyrics and continued with my observations that I had written before in the mid-eighties My Observations are mostly prose with poetic lilt. Observations include historical facts, conjecture, objective and subjective views and things that perplex me in life. The Observations that I write are more or less Op. Ed. in format. Although I grew up in Hamtramck, Michigan in the US my current residence is now in Cumby, Texas and I am happily married to my wife, Judy. I invite to listen to my guitar works www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Dead Hand You got to know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em, Know when to walk away and know when to run. You never count your money when you're sittin at the table. There'll be time enough for countin' when the dealins' done. David Reese too young to fold, David Reese a popular jack of all trades when it came to poker, The bluffing, the betting, the skill that he played poker, - was his ace of his sleeve. He played poker without deuces wild, not needing Jokers. To bad his lungs were not flushed out for him to breathe, Was is the casino smoke? Or was it his lifestyle in general? But whatever the circumstance was, he cashed out to soon, he had gone to see his maker, He was relatively young far from being too old. -

2018 SLU Mcnair Research Journal

THE SLU MCNAIR RESEARCH JOURNAL Summer 2018, Vol 1 Saint Louis University 1 THE SLU MCNAIR RESEARCH JOURNAL Summer 2018, Vol. 1 Published by the Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program St. Louis University Center for Global Citizenship, Suite 130 3672 West Pine Mall St. Louis, MO 63108 Made possible through a grant from the U.S. Department of Education to Saint Louis University, the Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program (McNair Scholars Program) is a TRIO program that prepares eligible high- achieving undergraduate students for the rigor of doctoral studies. These services are also extended to undergraduates from Harris-Stowe State University, Washington University in St. Louis, Webster University, University of Missouri St. Louis and Fontbonne University. The SLU McNair Research Journal is published annually and is the official publication of the Ronald E. McNair Post- Baccalaureate Achievement Program (McNair Scholars Program) at Saint Louis University. Neither the McNair Scholars Program nor the editors of this journal assume responsibility for the vieWs expressed by the authors featured in this publication. © 2018 Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program, Saint Louis University 2 Table of Contents MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR ...................................................................................... 4 MCNAIR PROGRAM ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS 2018 ............................................ 5 LIST OF 2018 MCNAIR SCHOLARS .................................................................................... -

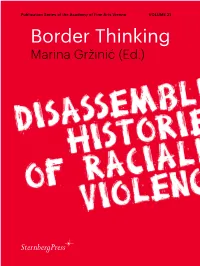

Border Thinking

Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna VOLUME 21 Border Thinking Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Border Thinking Disassembling Histories of Racialized Violence Marina Gržinić (Ed.) Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Eva Blimlinger, Andrea B. Braidt, Karin Riegler (Series Eds.) VOLUME 21 On the Publication Series We are pleased to present the latest volume in the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna’s publication series. The series, published in cooperation with our highly com- mitted partner Sternberg Press, is devoted to central themes of contemporary thought about art practices and theories. The volumes comprise contribu- tions on subjects that form the focus of discourse in art theory, cultural studies, art history, and research at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and represent the quintessence of international study and discussion taking place in the respective fields. Each volume is published in the form of an anthology, edited by staff members of the academy. Authors of high international repute are invited to make contributions that deal with the respective areas of emphasis. Research activities such as international conferences, lecture series, institute- specific research focuses, or research projects serve as points of departure for the individual volumes. All books in the series undergo a single blind peer review. International re- viewers, whose identities are not disclosed to the editors of the volumes, give an in-depth analysis and evaluation for each essay. The editors then rework the texts, taking into consideration the suggestions and feedback of the reviewers who, in a second step, make further comments on the revised essays. -

Fictions of the Self in Aleksandar Hemon's the Lazarus Project

Brno Studies in English Volume 37, No. 2, 2011 ISSN 0524-6881 DOI: 10.5817/BSE2011-2-14 Wendy Ward Does Autobiography Matter?: Fictions of the Self in Aleksandar Hemon’s The Lazarus Project Abstract In this article, I examine Bosnian writer Aleksandar Hemon’s relationship to and intervention in life-writing. Hemon’s fiction provides rich terrain for exploring the key shifts and obstacles facing the genre(s) at present by crossing national as well as aesthetic borders. In doing so, I trace his first autobiographical gestures in his earlier fiction against his recent insistence that his stories are “antibio- graphical” since they are the very “antimatter to the matter of my life. They con- tain what did not happen to me” – thus, an alternate, unrestrained space in which Hemon can flesh out multiple fictional selves. With his novel,The Lazarus Pro- ject, he delivers, in essence, a fictional biography on two levels: a main narrator (Brik) who enacts the author’s own exodus but also traces and retells an im- migrant stranger’s past (Lazarus) in order to work through his present conflicts, anger and sadness. The novel’s tensions between biography, autobiography and photography emerge from what Hemon calls a “conditional Americanness” that has overtaken the American Dream. Hemon employs photographic imagery not only to refute given notions of history and archive but also to craft a narrative imagination that builds on late German writer W. G. Sebald’s own transgressions within (auto)biographical writing, yet targets and questions more American and cross-cultural identity categories. Key words Autobiography; photography; Aleksandar Hemon; intermediality; immigrant identity; W. -

Bibliography & End-Notes

TESTIMONY Sources This is a compilation of sources I consulted while researching Testimony, both works that provided general information about recurring themes, e.g., Gypsy life, and ones that inspired specific statements in the novel. I mean to be forthright about the points of departure for my imagination, as well as to provide an opportunity for further reading for those who might be curious about the actual facts, remembering that Testimony is fiction, and not intended to be a reliable portrayal of any real-world person or event. BIBLIOGRAPHY Books Isabel Fonseca, Bury Me Standing, (Knopf, 1995) Available currently in a Vintage Departures edition. This book by a researcher who met and lived among various European Rom communities remains gorgeously written, intricately researched, and constantly moving. Ian Hancock, We Are the Romani People (University of Hertfordshire Press, 2002) An introductory guide to Rom culture. Professor Hancock, Rom by birth, is one of the world’s leading experts on Romnipen and his people, to whom he, understandably, remains fiercely loyal. Like Fonseca, he is occasionally criticized for being more advocate than scholar, but his works were invaluable to me, and this book is only one of several works of his that I consulted, including several of his lectures and interviews captured on YouTube. Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (Picador 2013). A deserving finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Non-Fiction, this book is a memoir in essays about Sasha’s movement from his boyhood in Bosnia to Chicago, from which he watched at a distance as the world he grew up in was savaged. -

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings

Ethnic Groups and Library of Congress Subject Headings Jeffre INTRODUCTION tricks for success in doing African studies research3. One of the challenges of studying ethnic Several sections of the article touch on subject head- groups is the abundant and changing terminology as- ings related to African studies. sociated with these groups and their study. This arti- Sanford Berman authored at least two works cle explains the Library of Congress subject headings about Library of Congress subject headings for ethnic (LCSH) that relate to ethnic groups, ethnology, and groups. His contentious 1991 article Things are ethnic diversity and how they are used in libraries. A seldom what they seem: Finding multicultural materi- database that uses a controlled vocabulary, such as als in library catalogs4 describes what he viewed as LCSH, can be invaluable when doing research on LCSH shortcomings at that time that related to ethnic ethnic groups, because it can help searchers conduct groups and to other aspects of multiculturalism. searches that are precise and comprehensive. Interestingly, this article notes an inequity in the use Keyword searching is an ineffective way of of the term God in subject headings. When referring conducting ethnic studies research because so many to the Christian God, there was no qualification by individual ethnic groups are known by so many differ- religion after the term. but for other religions there ent names. Take the Mohawk lndians for example. was. For example the heading God-History of They are also known as the Canienga Indians, the doctrines is a heading for Christian works, and God Caughnawaga Indians, the Kaniakehaka Indians, (Judaism)-History of doctrines for works on Juda- the Mohaqu Indians, the Saint Regis Indians, and ism. -

Thursday, February 08, 2018

Journal of the House ________________ Thursday, February 8, 2018 At one o'clock in the afternoon the Speaker called the House to order. Devotional Exercises Devotional exercises were conducted by Ebony Nyoni of Winooski, VT. House Bill Introduced H. 887 By Rep. Smith of Derby, House bill, entitled An act relating to establishing the Study Committee on Surveys of Land Burdened by Public Rights-of-Way; Which was read and referred to the committee on Transportation. Senate Bill Referred S. 179 Senate bill, entitled An act relating to community justice centers Was read and referred to the committee on Judiciary. House Resolution Adopted H.R. 19 House resolution, entitled House resolution recognizing the importance of the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. and Vermont Black communities Offered by: Representatives Morris of Bennington, Ancel of Calais, Bartholomew of Hartland, Briglin of Thetford, Burke of Brattleboro, Chesnut- Tangerman of Middletown Springs, Christie of Hartford, Cina of Burlington, Colburn of Burlington, Conquest of Newbury, Copeland-Hanzas of Bradford, Emmons of Springfield, Gonzalez of Winooski, Grad of Moretown, Head of South Burlington, Howard of Rutland City, Jessup of Middlesex, Krowinski of Burlington, LaLonde of South Burlington, Long of Newfane, Masland of Thetford, McCormack of Burlington, Miller of Shaftsbury, Rachelson of Burlington, Scheu of Middlebury, Sharpe of Bristol, Sheldon of Middlebury, 328 329 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 08, 2018 Stevens of Waterbury, Stuart of Brattleboro, Sullivan of Burlington, Toleno -

Balkan Minds: Transnational Nationalism and the Transformation of South Slavic Immigrant Identity in Chicago, 1890-1941

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations (1 year embargo) 2012 Balkan Minds: Transnational Nationalism and the Transformation of South Slavic Immigrant Identity in Chicago, 1890-1941 Dejan Kralj Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss_1yr Part of the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Kralj, Dejan, "Balkan Minds: Transnational Nationalism and the Transformation of South Slavic Immigrant Identity in Chicago, 1890-1941" (2012). Dissertations (1 year embargo). 4. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss_1yr/4 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations (1 year embargo) by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2012 Dejan Kralj LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO BALKAN MINDS: TRANSNATIONAL NATIONALISM & THE TRANSFORMATION OF SOUTH SLAVIC IMMIGRANT IDENTITY IN CHICAGO, 1890-1941 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY DEJAN KRALJ CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2012 Copyright by Dejan Kralj, 2012 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is quite a difficult task to thank everyone that has helped me throughout this epic scholarly journey. However, many deserve recognition for the roles they played guiding me through to the end of my graduate career. Foremost in mind, I must thank Lillian Hardison, the heart and soul of the history graduate department at Loyola. Your support and friendship have meant the world to me and countless other graduate students that have made their way through the program. -

Acbih.Org UNITED. MULTI-ETHNIC. DEMOCRATIC

UNITED. MULTI-ETHNIC. DEMOCRATIC. acbih.org 2007 - 2017 Celebrating a decade of 1510 H Street, NW, Suite 900 Washington, D.C. 20005 Bosnian-American advocacy Phone: (202) 347-6742 in Washington, D.C. [email protected] acbih.org 1 01/ WHO WE ARE 02/ A DECADE OF ADVOCACY 04/ SCHOLARSHIPS & FELLOWSHIPS 07/ CULTURAL PROMOTION 16/ UNITY & PARTNERSHIPS 16/ GIVING BACK 16/ JOIN US! 2 acbih.org The Advisory Council for Bosnia and Herzegovina (ACBH) is the leading independent, non-governmental organization dedicated to promoting the interests of Bosnian Americans and advocating for a united, multi-ethnic and democratic Bosnia and Herzegovina. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Adnan Hadrovic, Chairman Nedim Music, Vice Chairman Ida SeferRoche, Secretary Edina Skaljic, Treasurer Elmina Kulasic, Director of European Operations Adisada Dudic, Esq., Legal Adviser Ajla Delkic, President Dr. Mirsad Hadzikadic, Honorary Board Member Djenita Pasic, Esq., Honorary Board Member Haris Hromic, Honorary Board Member Mirzeta Hadzikadic, Honorary Board Member acbih.org 3 OBJECTIVES • Safeguarding the Bosnian American voice in Wash- ington, D.C. by providing outreach to U.S. policy and decision makers on issues that are relevant to the Bosnian American community. • Countering genocide denial and the revision of history. • Improving and promoting community involvement and participation of Bosnian Americans in the U.S. electoral and political processes. • Promoting and preserving the Bosnian and Herze- govinian heritage and identity through education. POLICY ISSUES • Supporting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. • Improving bilateral relations between the United States and Bosnia and Herzegovina. • Supporting Bosnia and Herzegovina’s aspiration to become a full-fledged member of the North Atlan- tic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU). -

Roguish Self-Fashioning and Questing in Aleksandar Hemon's

Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture Number 9 Roguery & (Sub)Versions Article 6 December 2019 Roguish Self-Fashioning and Questing in Aleksandar Hemon’s “Everything” Jason Blake University of Ljubljana Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/textmatters Recommended Citation Blake, Jason. "Roguish Self-Fashioning and Questing in Aleksandar Hemon’s “Everything”." Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture, no.9, 2020, pp. 100-117, doi:10.18778/2083-2931.09.06 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Text Matters: A Journal of Literature, Theory and Culture by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Text Matters, Number 9, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/2083-2931.09.06 Jason Blake University of Ljubljana Roguish Self-Fashioning and Questing in Aleksandar Hemon’s “Everything” A BSTR A CT This paper examines self-fashioning in Aleksandar Hemon’s “Everything,” a story about a Sarajevo teenager’s journey through ex-Yugoslavia to the Slovenian town of Murska Sobota. His aim? “[T]o buy a freezer chest for my family” (39). While in transit, the first-person narrator imagines himself a rogue of sorts; the fictional journey he takes, meanwhile, is clearly within the quest tradition. The paper argues that “Everything” is an unruly text because by the end of the story the reader must jettison the conventional reading traditions the quest narrative evokes. -

Bosnian Genocide Denial and Triumphalism: Origins

BOSNIAN GENOCIDE DENIAL AND TRIUMPHALISM: ORIGINS, IMPACT AND PREVENTION IMPACT ORIGINS, DENIAL ANDTRIUMPHALISM: BOSNIAN GENOCIDE BOSNIAN GENOCIDE DENIAL AND TRIUMPHALISM: ORIGINS, IMPACT AND PREVENTION Illustration © cins Edited by Sead Turčalo – Hikmet Karčić BOSNIAN GENOCIDE DENIAL AND TRIUMPHALISM: ORIGINS, IMPACT AND PREVENTION PUBLISHER Faculty of Political Science University of Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina IN COOPERATION WITH Srebrenica Memorial Center Institute for Islamic Tradition of Bosniaks ON BEHALF OF THE PUBLISHER Sead Turčalo EDITORS Hikmet Karčić Sead Turčalo DTP & LAYOUT Mahir Sokolija COVER IMAGE Illustration produced by Cins (https://www.instagram.com/ cins3000/) for Adnan Delalić’s article Wings of Denial published by Mangal Media on December 2, 2019. (https://www.mangalmedia.net/english//wings-of-denial) DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions of Publishers or its Editors. Copyright © 2021 Printed in Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnian Genocide Denial and Triumphalism: Origins, Impact and Prevention Editors: Sead Turčalo – Hikmet Karčić Sarajevo, 2021. Table of Contents Preface ..............................................................................7 Opening Statement by Ambassador Samantha Power .....9 PETER MAASS: The Second War: Journalism and the Protection of the Memory of Genocide From the Forces of Denial ..........................................15 MARKO ATTILA HOARE: Left-Wing Denial of the Bosnian Genocide ................................20 SAMUEL TOTTEN: To Deny the Facts of the Horrors of Srebrenica Is Contemptible and Dangerous: Concrete Recommendations to Counter Such Denial ...27 NeNad dimitrijević: Life After Death: A View From Serbia ....................................................36 ediNa Bećirević: 25 Years After Srebrenica, Genocide Denial Is Pervasive. It Can No Longer Go Unchallenged .........................42 Hamza Karčić: The Four Stages of Bosnian Genocide Denial .........................................................47 DAVID J. -

B ALTIC on 52 POC KET PR OGRAM Ma Y 25-28, 20 18

BALTICON 52 POCKET PROGRAM May 25-28, 2018 Note: Program listings are current as of Sunday, May 20 at 8 PM. For up-to-date information, please pick up a schedule grid, the daily Rocket Mail, or see our downloadable, interactive schedule at: https://schedule.balticon.org/ LOCATIONS AND HOURS OF OPERATION Locations and Hours of Operation 5TH FLOOR, ATRIUM ENTRANCE: • Info Desk • Volunteer Desk • Accessibility • Registration o Fri 1 PM – 10 PM o Sat 8:45 AM – 9 PM o Sun 8:45 AM – 7 PM o Mon 10 AM – 2 PM 5TH FLOOR , ATRIUM: • Con Suite: Baltimore A o Friday 4 PM through Monday 2 PM • Dealers’ Rooms: Baltimore B & Maryland E/F o Fri 2 PM – 7 PM o Sat 10 AM – 7 PM o Sun 10 AM – 7 PM o Mon 10 AM – 2 PM • Artist Alley & Writers’ Row o Same hours as Dealers, with breaks for participation in panels, workshops, or other events. • Art Show: Maryland A/B o Fri 5 PM – 7 PM; 9 PM – 10 PM o Sat 10 AM – 8 PM o Sun 10 AM – 1 PM; 2 PM – 5 PM o Mon 10 AM – noon • Masquerade Registration o Fri 4 PM – 7 PM o Sat 10 AM – 3 PM • Hall Costume Contest o Saturday only. Photos: 12 PM – 4 PM; Voting: 4 PM – 8 PM. • LARP Registration o Fri 5 PM – 9 PM o Sat 9 AM – 10:45 AM • Autographs: o See schedule 5TH FLOOR: • Con Ops: Fells Point (past elevators) o Friday 2 PM through Monday 5 PM • Hal Haag Memorial Game Room: Federal Hill o Fri 4 PM – 2 AM o Sat 10 AM – 2 AM o Sun 10 AM – 2 AM o Mon 10 AM – 3 PM BALTICON 52 POCKET PROGRAM 3 BSFS & BALTICON POLICY STATEMENTS • Sales Table: outside Federal Hill o Fri 2 PM – 7 PM o Sat 10:30 AM – 7:30 PM o Sun 10:30 AM – 7:30 PM o Mon 10:30 AM – 3 PM 6TH FLOOR: • Open Filk: Kent o Fri 11 PM – 2 AM o Sat 10 PM – 2 AM o Sun 10 PM – 2 AM o Mon 3 PM – 5 PM • Medical: Room 6017 INVITED PARTICIPANTS ONLY: • Program Ops: Fells Point (past elevators) o Fri 4 PM – 8 PM o Sat 9 AM – 5 PM o Sun 9 AM – Noon o Mon: contact Con Ops • Green Room: 12th Floor Presidential Suite o Fri 1 PM – 9 PM o Sat 9 AM – 7 PM o Sun 9 AM – 4 PM o Mon 9 AM – 4 PM Most convention areas will close by 2 AM each night.