Children's Literature Across Space and Time the Challenges Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Formal Approaches to Dps in Old Romanian Brill’S Studies in Historical Linguistics

Formal Approaches to DPs in Old Romanian Brill’s Studies in Historical Linguistics Series Editor Jóhanna Barðdal (Ghent University) Consulting Editor Spike Gildea (University of Oregon) Editorial Board Joan Bybee (University of New Mexico) – Lyle Campbell (University of Hawai’i Manoa) – Nicholas Evans (The Australian National University) Bjarke Frellesvig (University of Oxford) – Mirjam Fried (Czech Academy of Sciences) – Russel Gray (University of Auckland) – Tom Güldemann (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) – Alice Harris (University of Massachusetts) Brian D. Joseph (The Ohio State University) – Ritsuko Kikusawa (National Museum of Ethnology) – Silvia Luraghi (Università di Pavia) Joseph Salmons (University of Wisconsin) – Søren Wichmann (MPI/EVA) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bshl Formal Approaches to DPs in Old Romanian Edited by Virginia Hill LEIDEN | BOSTON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Formal approaches to DPs in Old Romanian / Edited by Virginia Hill. pages cm. — (Brill’s Studies in Historical Linguistics; Volume 5.) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-28771-6 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-29255-0 (e-book) 1. Romanian language—Syntax. 2. Romanian language—To 1500. 3. Romanian language—History. 4. Discourse analysis—History. 5. Pragmatics—History. 6. Historical linguistics. 7. Romania—History—To 1711. I. Hill, Virginia, editor. PC713.F67 2015 459’.5—dc23 2015010249 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 2211-4904 isbn 978-90-04-28771-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-29255-0 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Beatrix Potter Studies

Patron Registered Charity No. 281198 Patricia Routledge, CBE President Brian Alderson This up-to-date list of the Society’s publications contains an Order Form. Everything listed is also available at Society meetings and events, at lower off-the-table prices, and from its website: www.beatrixpottersociety.org.uk BEATRIX POTTER STUDIES These are the talks given at the Society’s biennial International Study Conferences, held in the UK every other year since 1984, and are the most important of its publications. The papers cover a wide range of subjects connected with Beatrix Potter, presented by experts in their particular field from all over the world, and they contain much original research not readily available elsewhere. The first two Conferences included a wide range of topics, but from 1988 they followed a theme. All are fully illustrated and, from Studies VII onwards, indexed. (The Index to Volumes I-VI is available separately.) Studies I (1984, Ambleside), 1986, reprinted 1992 ISBN 1 869980 00 X ‘Beatrix Potter and the National Trust’, Christopher Hanson-Smith ‘Beatrix Potter the Writer’, Brian Alderson ‘Beatrix Potter the Artist’, Irene Whalley ‘Beatrix Potter Collections in the British Isles’, Anne Stevenson Hobbs ‘Beatrix Potter Collections in America’, Jane Morse ‘Beatrix Potter and her Funguses’, Mary Noble ‘An Introduction to the film The Tales of Beatrix Potter’, Jane Pritchard Studies II (1986, Ambleside), 1987 ISBN 1 869980 01 8 (currently out of print) ‘Lake District Natural History and Beatrix Potter’, John Clegg ‘The Beatrix -

The Tale of Peter Rabbit, Group 1

The Tale of Peter Rabbit Fun things to do! Babies like looking at their favourite This is the first book every baby or child books often. Try making time each day receives from the Imagination Library to go through your baby’s favourite book together. Doing the same thing at the same time each day builds good habits. The Tale of Peter Rabbit was first Good to know published by Frederick Warne in Having a set time for reading will help your baby to recognise a routine, 1902 and endures as Beatrix Potter’s which helps them feel safe and secure. For more information visit most popular and well-loved tale. It Words for Life: https://wordsforlife.org.uk/activities/baby-book-time/ tells the story of a very mischievous rabbit and the trouble he encounters in Mr McGregor’s vegetable garden! Visit the fabulous Tiny Happy People website to help you develop your child's communication skills. Explore the simple activities and play ideas and find out about their amazing early development. Welcome from North Lincolnshire to the Imagination Library. This is the www.bbc.co.uk/tiny-happy-people first of many books which will be delivered to your home. Please keep and treasure the books you receive to create your own library. Every book will help as your child grows and develops, starts to talk and then read for themselves. To find out more about why Dolly launched the Imagination library use this link: dollyparton.com/imagination-library Imagination Library Newsletter Making ten minutes a day to share books with Have you subscribed to our free monthly Imagination Library Newsletter? your child will make a huge Each month you will receive ideas and activities for the books you difference to their development receive: https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/UKNOLC/subscriber/new www.northlincs.gov.uk/imagination-library . -

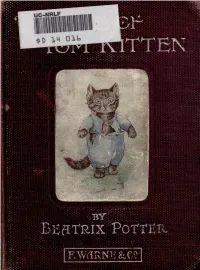

The Tale of Tom Kitten

.TTEN Title: The Tale of Tom Kitten Author: Beatrix Potter Language: English Subject: Fiction, Literature, Children's literature Publisher: World Public Library Association Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net World Public Library The World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net is an effort to preserve and disseminate classic works of literature, serials, bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other reference works in a number of languages and countries around the world. Our mission is to serve the public, aid students and educators by providing public access to the world's most complete collection of electronic books on-line as well as offer a variety of services and resources that support and strengthen the instructional programs of education, elementary through post baccalaureate studies. This file was produced as part of the "eBook Campaign" to promote literacy, accessibility, and enhanced reading. Authors, publishers, libraries and technologists unite to expand reading with eBooks. Support online literacy by becoming a member of the World Public Library, http://www.WorldLibrary.net/Join.htm. Copyright © 2008, All Rights Reserved Worldwide by World Public Library, www.WorldLibrary.net www.worldlibrary.net *This eBook has certain copyright implications you should read.* This book is copyrighted by the World Public Library. With permission copies may be distributed so long as such copies (1) are for your or others personal use only, and (2) are not distributed or used commercially. Prohibited distribution includes any service that offers this file for download or commercial distribution in any form, (See complete disclaimer http://WorldLibrary.net/Copyrights.html). World Public Library Association P.O. -

Animated Stories by Beatrix Potter

The Brompton Tales Animated stories by Beatrix Potter Summary The Brompton Tales is a 14 part TV series that brings Beatrix Potter’s World of Peter Rabbit to life . Told to generations of children all over the world for the last century, these unique stories are wholesome and fun, yet they provide some valuable basic lessons for young children. Specs Over 45 millions copies of “The tale of Peter Rabbit” alone have been sold worldwide, Aspect Ratio together with numerous films and adaptations. Beatrix Potter’s stories are as loved today as 16 x 9 they were when first published over one hundred years ago. Resolution UHD Each episode is told by the enchanting voice of Perdita Avery. The story telling has been Framerate 3840 x 2160 kept true to the original text of the books with a few changes to some words that have 25fps lost their meaning over time in the modern english language. Perdita Avery’s voice is a Audio received pronunciation and very easy to understand. Bit Depth Stereo Each episode contains all of the drawings that feature in the books and are carefully brought Sample Rate 24 Bit to life with subtle animations to enhance the images and create movement all in stunning 48,000 Hz 4K. Format WAV (uncompressed) The most well known episode is of course “The Tale of Peter Rabbit”. The Tale of Peter Rabbit was first published by Frederick Warne in 1902 and endures as- Be atrix Potter’s most popular and well-loved tale. It tells the story of a very mischievous rabbit and the trouble he encounters in Mr McGregor’s vegetable garden! The series provides fourteen episodes that total run time of 145 minutes. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q0q765 Author Browning, Catherine Cronquist Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature By Catherine Cronquist Browning A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor Paula Fass Fall 2013 Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature © 2013 by Catherine Cronquist Browning Abstract Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature by Catherine Cronquist Browning Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature analyzes the history of the child as a textual subject, particularly in the British Victorian period. Nineteenth-century literature develops an association between the reader and the child, linking the humanistic self- fashioning catalyzed by textual study to the educational development of children. I explore the function of the reading and readable child subject in four key Victorian genres, the educational treatise, the Bildungsroman, the child fantasy novel, and the autobiography. I argue that the literate children of nineteenth century prose narrative assert control over their self-definition by creatively misreading and assertively rewriting the narratives generated by adults. The early induction of Victorian children into the symbolic register of language provides an opportunity for them to constitute themselves, not as ingenuous neophytes, but as the inheritors of literary history and tradition. -

100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators

Page i 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Page ii POPULAR AUTHORS SERIES The 100 Most Popular Young Adult Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. Revised First Edition. By Bernard A. Drew. Popular Nonfiction Authors for Children: A Biographical and Thematic Guide. By Flora R. Wyatt, Margaret Coggins, and Jane Hunter Imber. 100 Most Popular Children's Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. By Sharron L. McElmeel. 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. By Sharron L. McElmeel. Page iii 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies Sharron L. McElmeel Page iv Copyright © 2000 Sharron L. McElmeel All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. P.O. Box 6633 Englewood, CO 801556633 18002376124 www.lu.com Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data McElmeel, Sharron L. 100 most popular picture book authors and illustrators : biographical sketches and bibliographies / Sharron L. McElmeel. p. cm. — (Popular authors series) Includes index. ISBN 1563086476 (cloth : hardbound) 1. Children's literature, American—Biobibliography—Dictionaries. 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. Illustrators—United States—Biography—Dictionaries. 4. Illustration of books—Biobibliography—Dictionaries. 5. Illustrated children's books—Bibliography. 6. Picture books for children—Bibliography. I. Title: One hundred most popular picture book authors and illustrators. -

Recent Anglicisms in Romanian

207 RECENT ANGLICISMS IN ROMANIAN Hortensia Parlog, University of Timisoara In the years after the fall of the communist regime in 1989, when Ro• mania opened to the West, the influence of English on the Romanian lan• guage rose to an unprecedented level. Nowadays, English words can be found in all Romanian newspapers and journals, can be heard on any Romanian TV channel, and are frequently used as shop or business names (Parlog 2002); English has even become the language of Romanian graffiti. The phenomenon has been most recently charted in the three volumes on European Anglicisms edited by Manfred Görlach (2001; 2002a; 2002b). A previous article on English loanwords in Romanian, published twenty years ago (Parlog 1983), was based on a corpus in which only eighteen nouns referred to human beings. The current corpus, collected since 1990 from several newspapers and magazines of different orienta• tion, contains more than six times as many (see Annex).1 With some ex• ceptions, they denote human agents or members of a profession and many do not represent random usage but seem to occur regularly. Their gradual adaptation to Romanian is governed by formal and semantic cri• teria. From a formal point of view, borrowed names of human agents end• ing in a consonant or a semivowel may become either masculine or neuter in Romanian and the difference becomes obvious only in the plural forms; from a semantic point of view, however, such nouns usually become mas• culine while the neuter is reserved for nouns with non-animate referents. Many of the borrowed English words are used unmodified, without any change in their formal structure e.g.: 208 Nordic Journal of English Studies o pozitie de outsider ["a position of outsider"];2 angajeazä brand manager, creative director, account manager, art director, account executive, copywriter, designer ["wanted ..."]; locuri de muncäpentru baby-sitter ["jobs as baby-sitter"]; and A.N., hostess de night-club ["A.N., night-club hostess"]. -

Of Academy of Sciences

OF ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF MOLDOVA YOU CAN TEACH A STUDENT A LESSON FOR A DAY, BUT IF YOU CAN TEACH HIM TO LEARN BY CREATING CURIOSITY, HE WILL CONTINUE THE LEARNING PROCESS AS LONG AS HE LIVES. Clay P. BEDFORD DEAR FRIENDS, Thoughts about the future of Moldova make us understand that its welfare strongly depends on the Science, which is the base of the perpetual progress. Thinking about you, scientists of tomorrow, who have to put your shoulder to the creation of the knowledge based society, we make the base of this modern hostel which will be one of the important backgrounds for the preparing of young researchers - the future of national science. Become professionals, state personalities, remarkable scientists On behalf of the Moldovan Scientific Community I would like to great the young generation of Moldova and invite them to participate actively in the science and technology development. The Academy of Sciences of Moldova creates a lot of opportunities for the young generation for scientific carrier pursuit: - Modern Research, Education and Innovation, Environment - State-of-the-art equipment - Connection to the R & D institutions in Moldova and abroad - Involvement of the experienced Teachers and Professors in education process - Participation in the International Projects: FP7, TEMPUS, NATO,… - Collaboration development with Scientific diaspora. You are welcome to accumulate all these opportunities. On you depends the future of knowledge triangle: research – education – innovation development in Moldova. From the bottom of our heart we wish you to be happy. Scientific activity should bring you just satisfaction. You have to carry on the baton received from the forerunners. -

Dative Constructions in Romance and Beyond

Dative constructions in Romance and beyond Edited by Anna Pineda Jaume Mateu language Open Generative Syntax 7 science press Open Generative Syntax Editors: Elena Anagnostopoulou, Mark Baker, Roberta D’Alessandro, David Pesetsky, Susi Wurmbrand In this series: 1. Bailey, Laura R. & Michelle Sheehan (eds.). Order and structure in syntax I: Word order and syntactic structure. 2. Sheehan, Michelle & Laura R. Bailey (eds.). Order and structure in syntax II: Subjecthood and argument structure. 3. BacskaiAtkari, Julia. Deletion phenomena in comparative constructions: English comparatives in a crosslinguistic perspective. 4. Franco, Ludovico, Mihaela Marchis Moreno & Matthew Reeve (eds.). Agreement, case and locality in the nominal and verbal domains. 5. Bross, Fabian. The clausal syntax of German Sign Language: A cartographic approach. 6. Smith, Peter W., Johannes Mursell & Katharina Hartmann (eds.). Agree to Agree: Agreement in the Minimalist Programme. 7. Pineda, Anna & Jaume Mateu (eds.). Dative constructions in Romance and beyond. ISSN: 25687336 Dative constructions in Romance and beyond Edited by Anna Pineda Jaume Mateu language science press Pineda, Anna & Jaume Mateu (eds.). 2020. Dative constructions in Romance and beyond (Open Generative Syntax 7). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/258 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-249-5 (Digital) 978-3-96110-250-1 -

The Enduring Tale of Beatrix Potter by Val Baynton

The Enduring Tale of Beatrix Potter by Val Baynton ‘Once upon a time there were four little Rabbits, and their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cotton-tail, and Peter.’ This, the opening sentence of The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter, must be one of the most famous openings to a children’s book. First published privately by Potter, it began her career as a children’s author, but it represents just one aspect of the life of this extraordinary lady. A fuller biography was explored in the film Miss Potter, released in the UK on 5th January 2007, which told the story of how Beatrix developed her artistic and story-telling abilities from a young age and rebelled against the conventions of the time by refusing to marry for the sake of it. The film, starring Renée Zellweger as Beatrix Potter and Ewan McGregor as Norman Warne, received mixed reviews with some critics describing it as ‘twee’ and not liking the way Beatrix’s drawings of characters such as Peter Rabbit or Jemima Puddleduck were animated. Others described it as ‘enchanting’, ‘the right balance of pathos, humour and romance’ and ‘an entertaining trifle, but a trifle nevertheless.’ One of the best biographies published about Beatrix Potter is by Judy Taylor. Beatrix Potter Artist, Storyteller and Countrywoman, recounts Potter’s story from her Victorian childhood in London to her final years farming in the Lake District. Regarded as a standard work on Beatrix Potter’s life, the book has been updated regularly to include fresh material and previously unpublished photographs that have come to light. -

Great Big Treasu Ry of Beatrix Potter Great Big Treasu Ry of Beatrix Potter

Picture here Great Big Treasury of Beatrix Potter By Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) Born in Victorian London on July 28th, 1866, Beatrix Potter created some of the best-loved children’s stories of all time. Starting with Peter Rabbit and moving through the rest of these delightful tales, the Great Big Treasury of Beatrix Potter will warm the hearts both of those who remember her fondly from their childhoods and those who discover for the first time the magic of these timeless stories. (Summary by Chip) Great Big Treasury of Beatrix TreasuryPotter Great Beatrix of Big 01 – The Tale of Peter Rabbit, read by Kara Shallenberg – 00:06:49 02 – The Tailor of Gloucester, read by Marilyn Saklatvala – 00:17:21 03 – The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, read by Sherry Crowther – 00:08:50 04 – The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, read by Geva – 00:06:33 05 – The Tale of Two Bad Mice, read by Hugh McGuire – 00:07:29 06 – The Tale of Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle, read by Jeremy – 00:09:13 07 – The Pie and the Patty-Pan, read by wedschild – 00:09:27 08 – The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher, read by retswerb – 00:06:11 09 – The Story of a Fierce Bad Rabbit, read by Brad Bush – 00:01:23 10 – The Story of Miss Moppet, read by Betsie Bush – 00:02:06 11 – The Tale of Tom Kitten, read by Neils Clemenson – 00:05:13 12 – The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, read by Brad Bush – 00:07:57 13 – The Roly-Poly Pudding, read by Vlooi – 00:19:19 14 – The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies, read by Annie Coleman – 00:08:13 15 – The Tale of Mrs.