The Relationship Between the Constitutional Right to Silence and Confessions in Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imo Police Command Moves Five Luxury Buses of Policemen to Edo Pg

Imo police command moves five luxury buses of policemen to Edo pg. 3 Kidnappers kill DSS operative Nsukka women after N5m ransom against lawmakers’ pg. 7 poor performance pg. 2 ...Strong voice echoes the truth ISSN: 2736-0512 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 2020 VOL. 1 NO. 9 N150 Ikpeazu Ugwuanyi Biafra pg. 2 Reason Nigeria can’t work Kanu Madiebo Ojukwu Abia health workers protest Information Minister on facility 14 months unpaid salaries tour of Walter Smith refinery, Ohaji pg. 3 pg. 2 Mother seeks justice over alleged Police arrest child trafficking syndicate, rape of her 7year old daughter pg. 3 rescues 8 children in Anambra pg. 6 Wednesday, September 16, 2020 representatives have to take the Abia commissioner canvasses media launch to the states and local government levels. Biafra computer literacy for women Dr Okaro said, “we appeal to you for your support and assistance Why Nigeria can't work From Dan Maduagwu, Umuahia products instead of depending on to ensure that the project succeeds, their husbands and children all the bia State Commissioner for so that our women benefits Women Affairs and Social time. maximally from its provisions" Ex war general reveals She appealed to the members of ADevelopment, Chief Mrs Imo water corporation the delegation to be steadfast, By Peter Aneme alternative, but to seek resistance Ukachi Amala has advocated basic workers lament 8 months' through secession". computer training for women in the adding that the assignment is civil war veteran and the voluntary while also warning salary arrears He explained in details, "The state as a basis for them to benefit man who commanded from the Economic Community of against division in the organization. -

Curriculum Vitae of PROF. IMRAN OLUWOLE SMITH, SAN, FCI

Curriculum Vitae of PROF. IMRAN OLUWOLE SMITH, SAN, FCI Arb (UK), FCTI School of Law, SOAS University of London Thornhaugh Street Bloomsbury, London United Kingdom Phone: +44 7488701801 +234 8037736780 E-mail:[email protected] [email protected] PERSONAL DETAILS SURNAME: SMITH OTHER NAMES: Imran Oluwole NATIONALITY: Nigerian/British CORRESPONDENCE ADDRESS: 33 Shawbrooke Road, London SE9 6AL MARITAL STATUS: Married ______________________________________________________________________________ INSTITUTIONS ATTENDED WITH DATES • Oxford City Academy, Oxford, United Kingdom (2018) • Hague Academy of International Law, Netherlands (1989) • University of Lagos, (1984-1985), (1979-1982) • Nigerian Law School (1982-1983) • Ansar-Ud-Deen Grammar School, Suru-lere-Lagos (1971-1976) ______________________________________________________________________________ ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS WITH DATES • Master of Laws (LL.M) 1985 • Bachelor of Laws LL.B (Hons) 1982 • General Certificate of Education, Advanced Level 1977 • West African School Certificate 1976 _____________________________________________________________________________ PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS/ELEVATION WITH DATES • Senior Advocate of Nigeria, 2010 • Solicitor of the Supreme Court of England and Wales, 2007 • Barrister and Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, 1983 _____________________________________________________________________________ EMPLOYMENT • Lecturer/Professor of Law, University of Lagos, Nigeria (November 1999 to date) • Lecturer in Law, Lagos State University, Nigeria (January1986 to November 1999) 1 CURRENT ACADEMIC STATUS • Professor of Private and Property Law, University of Lagosw.e.f October 2003. WORK EXPERIENCE IN THE UNIVERSITY SYSTEM A. TEACHING Lecturer in law at the Lagos State University, Lagos-Nigeria (1986-1999) • Taught Land law, Conveyancing, Equity and Trust at the undergraduate level; Law of secured credit and International Environmental law at the post graduate level. • Supervised a total of 46 undergraduate long essays. • Supervised a total of 25 LL.M dissertations. -

1 2 Nigerian Diaspora Investment Summit | 3 TABLE of CONTENT

Nigerian Diaspora Investment Summit | www.ndis.gov.ng 1 2 Nigerian Diaspora Investment Summit | www.ndis.gov.ng 3 TABLE OF CONTENT 04 PROGRAM OF EVENT 08 ABOUT NIGERIA DIASPORA INVESTMENT SUMMIT 2018 23 SUMMARY REPORT & GALLERY OF THE INAUGURAL NIGERIA DIASPORA INVESTMENT SUMMIT 2018 39 MEET THE MEMBERS 2 Nigerian Diaspora Investment Summit | www.ndis.gov.ng 3 PROGRAM THEME: Activating Diaspora Investments for a Diversified Economy. VENUE: State House Banquet Hall, Aso Villa, Abuja. DATE: 27th – 29th November, 2018. DAY 1: TUESDAY, 27THNOVEMBER, 2018 Summit Coordinator: Dr. Badewa Adejugbe-Williams Programme Coordinator: Theodore O. P. Sefia Esq. Rapportéur-General: Mrs. Marie David 07:00 Arrivals and Registration 08:55 All Participants Seated COMMENCEMENT Rapportéurs: Samuel Audu Ibrahim & Ms. Olayinka Solange Kuye-Romelus 09:00 National Anthem 09:05 Welcome Remarks by Senior Special Assistant to the President on Foreign Affairs and the Diaspora, Hon. Abike Dabiri-Erewa. 09:10 Goodwill Messages by: i. Chair, Events Committee, Nigerian Diaspora Alumni Network (NiDAN), Dr. Mrs. Badewa Adejugbe-Williams. ii. Executive Secretary/Chief Executive Officer, Nigeria Investment Promotion Commission (NIPC), Ms. Yewande Sadiku iii. Honourable Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. Geoffrey Onyeama. 09:20 Address by Secretary to the Government of the Federation (SGF), Mr. Boss Mustapha. 09:25 Keynote Speech, The Diaspora: Investing for Growth and Development, by His Excellency, Rwandan High Commissioner to Nigeria, Mr. Kamanzi Stanislas. 09:45 Group Photographs NETWORKING AND REFRESHMENTS BREAK FIRST PLENARY SESSION – THEMATIC PRESENTATIONS Chairman: Mr. Godwin Emefiele, Governor, Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). Rapportéurs: Olusegun Akintoye & Olajumoke Usifoh 10:30 Plenary Presentation: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and the Capital Market: Promoting Diversified Economic Growth – Director General, Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), Ms. -

Olukunle Edun Ll.B, B.L, Ll.M

OLUKUNLE EDUN LL.B, B.L, LL.M RESUME PERSONAL DETAILS Name: Edun O. Olukunle Place of Birth: Ibadan State of Origin: Ogun State Mobile/Home No: +234-8038695936 Date of Birth: 31st March 1974 Email: [email protected] Academic Sojourn University of Benin, Benin City …………………..2006 (LL.M) Nigerian Law School, Abuja.……………………….1998 - 1999 (2.1) Ogun State University, Ago-Iwoye…………….1991- 1997 (LL.B) Ogun State Polytechnic, Abeokuta…………….1991 Rev. Kuti Mem. Gramm. Sch. Abeokuta……1986-1990 (SSCE) Essi College , Warri …………………………………1985 Pessu Primary Sch. Warri………………………1979-1985 BAR ACTIVITIES: Presently, National Publicity Secretary, Nigerian Bar Association. Member, 2019 and 2020 NBA AGC Technical Committee on Conference Planning. Chairman, Publicity & Media Sub Committee, 2019 and 2020 AGC. Member, National Executive Committee, NBA 2016-till date. Member, NBA Human Right Institute (NBA-HRI) 2016- 2018 Member, Governing Council, SPIDEL (2016-2018). Member, NBA National Assets Management Committee 2014-2016 Past Vice Chairman, NBA Warri 2016-2018. Past Chairman, NBA Warri Human Right Committee 2016-2018. Past Chairman, NBA Warri Ad Hoc Committee on Members' Insurance 2016-2018. Past Chairman, NBA Warri Public Interest Litigation Committee 2014-2016 Past Chair, NBA Warri Fake Lawyers and NBA Car Sticker Committee 2014-2016. Member, NBA Warri 2017 Select Committee: Workshop on the Delta State Administration of Criminal Justice Law. Member, NBA Warri Special Publication Committee that compiled and published "Selected Judgments of the Late Hon. Justice F.O. Ohwo" 2018. Chair,NBA Warri Committee on"State of the Courts in Warri, Effurun and Udu" 2017. Member, MWBF 5 Man Committee to study and appraise the Senator Godswill Akpabio's proposed amended Legal Practitioners' Bill-2018. -

Defected Aspirants Won't Be Missed by APC, Says Group

Four killed, 50 houses razed in fresh Plateau hostility Anambra Guber: A functional lateau State Police Miango community and c o n f i r m e d t h a t , “ O n C o m m a n d h a s Fulani herders over an age- 31/07/2021, the Command Pc o n f i r m e d f o u r long land crisis in the locality. received a report that there LG will make persons were killed and 50 A c c o r d i n g t o t h e was a conflict between Defected aspirants houses razed down in a command, three persons were gunmen suspected to be renewed hostilities between said to have been injured in Fulani Militia and youth from life more Fulani Militia and Irigwe the bloody clashes that lasted Irigwe at Jebbu Miango, natives of Bassa LGAs on for hours, while four persons Bassa LGA of Plateau State. won't be missed by abundant Saturday night at Jebbu were shot dead, with about 50 “Unfortunately, fifty Miango locality. houses burnt down. houses were torched and four It was gathered on Sunday The spokesman of the natives were also shot dead. from the police authorities in P l a t e a u S t a t e P o l i c e “Upon receipt of the APC, says group Jos that the hostilities were Command, ASP. Gabriel report, the tactical team of the PAGE 16 between Irigwe youths in the U b a h i n a s t a t e m e n t PAGE 3 Continued on page 3 Vol. -

Corruption in Electricity Report A4

“From Darkness to Darkness” "From Darkness To Darkness" How Nigerians are Paying the Price for Corruption in the Electricity Sector © Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) Lagos, Nigeria August 2017 How Nigerians are paying the price for corruption in the electricity sector Page 01 “From Darkness to Darkness” ISBN: 978-978-960-645-2 First Published in Nigeria, 2017 © August 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without the expressed permission of the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP). Published by: SOCIO-ECONOMIC RIGHTS AND ACCOUNTABILITY PROJECT (SERAP) 2B Oyetola Street Off Ajanaku Street, Off Salvation Street, Opebi Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria. Printed in Nigeria by Eddy Asae Press 0802 325 1446, 0806 018 2441 Page 02 How Nigerians are paying the price for corruption in the electricity sector “From Darkness to Darkness” Acknowledgments The Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project (SERAP) extends its sincere appreciation to all those who were involved in the production and publication of this report. SERAP would like to thank the MacArthur Foundation, USA, for its generous support, which made the publication of this report possible. We also thank our consultant Yemi Oke, Associate Professor, Energy/Electricity Law, Faculty of Law, University of Lagos for his excellent work on the report. Dr Oke had his LL.M and PhD degrees from Osgoode Hall Law School, York University, Canada; LL.B from University of Ilorin, Nigeria; B.L. from the Nigerian Law School, Abuja. He specializes in Electricity Law, Energy Resources and Environmental Law. He is the author of the pioneering electricity law textbook in Nigeria, titled “Nigerian Electricity Law and Regulation”. -

Curriculum Vitae Section A: General Information 1

CURRICULUM VITAE SECTION A: GENERAL INFORMATION 1. a. Name: Dr. Theophilus Chinedu NWANO b. Place and Date of Birth: Lagos, 9/02/1978 c. Home Address: 77, Adetola Street, Aguda Surulere, Lagos. d. Sex: Male e. E-mail: [email protected] f. Phone (Mobile ): +234 8033372420, g. Nationality: Nigerian h. State of Origin Imo i. Marital Status: Married j. Current Position Senior Lecturer SECTION B: ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS Schools attended with Dates 1. United Primary School Ilorin 1984-1990 2. Government High School, Ilorin 1990-1996 3. Lagos State University, Ojo 1998-2003 4. Nigerian Law School Abuja 2004-2005 5. Lagos State University, Ojo 2007-2008 6. Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma 2012- 2018 A. Degrees Obtained with Dates 1. Bachelor of Laws (LL.B), 2004 Lagos State University (Second Class Honours, Upper Division) 2. Barrister at Law (B.L), 2005 Nigerian Law School, Abuja (Second Class Honours Lower Division) 3. Master of Laws (LL.M), 2008 Lagos State University, (PhD Grade) 4. Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D), 2019 Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma Page 1 of 8 SECTION C: PROFESSIONAL PROFILE Teaching and Professional Experience 1. Legal Practice (February 2006- August 2009) M. A. Ashimi & Co., 78 Bambgose street, Lagos Island, Lagos 2. Lecturer in Law, Faculty of Law, Benson Idahosa University i. October 2009- October 2012 Lecturer II ii. October 2012- to 2018 Lecturer I iii. October 2018- to Date Senior Lecturer Courses Taught Include: a. Criminal Law, 2009- Date b. International Law, 2009-2012 c. Law of Torts, 2011-2015 d. Land Law, 2011- Date e. Clinical Legal Education, 2012 - Date f. -

Of Paporderpaper.Ng) ER Tvodayol 1

O(A specialR commemorativeDER edition of PAPOrderPaper.ng) ER TVODAYOL 1. NO. 1 SEPTEMPTER 2016 Secrecy of NASS Budget Whistleblowers and anti-corruption war Meet the New Clerk of the National Assembly Movers&Shakers of the National Assembly Happening today (Monday, September 26, 2016) THE GALLERY COLLOQUIUM ON BUDGETARY REFORMS Venue: Ladi Kwali Hall, Sheraton Hotel and Towers, Abuja Time: 10am prompt 2 ORDERPAPERTODAY | September 2016 September 2016 | ORDERPAPERTODAY 3 EDITor’S NOTE t is with immense delight that I introduce to you this commemorative edition of ORDERPAPERTODAY, a special print publication of OrderPaper.ng. We are essentially an online newspaper dedicated to reporting and tracking the IParliament (both the National and State Assemblies) in Nigeria. Part of our mission is also to offer citizens a veritable platform to interface and engage with their representatives in the legislature. In summary OrderPaper.ng is a medium designed to serve legislative news to citizens and offer them a much-desired channel of communication with those they elected to make laws and ensure good governance. So the fact that you have this copy in your hand and going through these lines and subsequent pages is very gratifying to all of us in the editorial team. For us this is a milestone achievement. And not just because this special issue commemorates the formal public presentation of OrderPaper.ng but because it also signposts the hosting of the maiden The Gallery Colloquium convened to interrogate Nigeria’s budgetary process and offer suggestions on how the nation’s annual budgets can be made to work towards delivering the goods of democracy to the greater majority of citizens. -

PARTNERS WEST AFRICA NIGERIA Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative (PWAN) LEGAL AID DIRECTORY

PARTNERS WEST AFRICA NIGERIA Rule of Law And Empowerment Initiative (PWAN) LEGAL AID DIRECTORY SUPPORTED BY THE NIGERIA POLICING PROGRAMME coffey Supporting National Policing to Respond Locally Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative also known as Partners West Africa Nigeria NPP (PWAN) is a nongovernmental organization dedicated to enhancing citizens’ participation and improving security governance in Nigeria and West Africa broadly. Twitter- @partnersnigeria Facebok- @partnersnigeria www.partnersnigeria.org I SOCIAL ACCOUNTABILITY in the JUDICIAL SECTOR SUPPORTED BY US Embassy Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement LEGAL AID DIRECTORY IN NIGERIA II RULE OF LAW AND EMPOWERMENT INITIATIVE also known as PARTNERS WEST AFRICA-NIGERIA (PWAN) Editors: ‘Kemi Okenyodo Barbara Shitnaan Maigari Copyright © 2018 by Rule of Law and Empowerment Initiative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of PWAN. III LEGAL AID DIRECTORY iii JUSTIFICATION AND OBJECTIVE FOR CREATING A NIGERIAN LEGAL AID DIRECTORY Section 35 of The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria1999 (CFRN 1999) (as amended) guarantees the right of a suspect or an accused person to bail. Likely, Section 36(6)(c) guarantees the right of a defendant to defend himself in person or by any lawyer of his choice. Notwithstanding the above provisions, majority of Nigerians, particularly the vulnerable persons like women, children, the elderly and persons with disabilities etc are deprived of their right of access to justice because they cannot afford legal services. This is so because according to the Central Intelligence Agency(CIA)1, “over 62% of Nigeria’s 170 million people still live in extreme poverty”, and as such engaging the services of an lawyer when the need arises would appear as a superfluous luxury, contrary to the Fundamental Rights provisions of The CFRN 1999(as amended). -

INTRODUCTION This Paper Seeks to Draw Upon the Experiences of Nigeria As a Growing Mediation Movement to Serve As a Blueprint for Emerging Mediation Movements

INTRODUCTION This paper seeks to draw upon the experiences of Nigeria as a growing mediation movement to serve as a blueprint for emerging mediation movements. Nigeria, often described as the most populous black nation has a current estimated population of 200 million (200,963,599)1 and is divided into 36 states with the Federal Capital Territory (F.C.T.) as the political seat. The commercial centre which is Lagos state, is about 3, 577 sq.km in size and has a current estimated population of 14,862,1112. With this population and the number of businesses based in Lagos, it is inevitable that there will be substantially a greater number of disputes in Lagos State than all the other States in Nigeria. Pre-colonial African societies normally resolved disputes through four hierarchically related options.3 First, the disputants tried to resolve the disputes by themselves; what is now known as negotiation. If that failed, they sought the assistance of kinsmen; what is now known as mediation. If this also failed, the dispute was taken to the Headman of the defendant’s neighbourhood; what is now known as ‘neutral evaluation’. If this also failed, the matter was then taken to the High Chief or King for a binding decision; what is now known as arbitration.4 This hierarchical approach was also practised by the three predominant tribes in Nigeria; Yoruba, Igbo and Hausa, prior to colonisation5 This system was jettisoned with the advent of colonialization and traditional legal systems branded as “repugnant to natural justice”6 The growing demands for “modern justice” relegated the better understood traditional channels to the background.7 The Nigerian Legal System is a reflection of the federal character of the Nigerian society. -

Senior Advocate of Nigeria(SAN)

Senior Advocate of Nigeria(SAN) No. 20, Etang O. Obuli Crescent, Jabi, Abuja SUMMARY Age: – 55 years Gender: – Male Profession: – Legal Practice Experience: – 28 years of uninterrupted full time legal practice as Solicitor and attorney at trial and appellate courts in Nigeria. Special Areas of interest: – Constitutional and Electoral Law litigation, Corporate and Commercial Law practice, Labour Law disputes, defence attorney in criminal law matters. Professional Excellence: – Conferred with the rank of Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN) in August, 2011, in recognition of outstanding professional competence, loyalty, ability and integrity as advocate; and for significant contribution to the development of the legal profession in Nigeria. Page | 1 PERSONAL DETAILS:- Date of Birth: – 20th May, 1963 Place of Birth: – Enugu, Nigeria Nationality: – Nigerian State of Origin: – Cross River Local Government Area: – Biase Marital Status: – Married Mobile Numbers: – +234-8035883474; +234-8058116191 Email Address: – [email protected] EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS S/N Institution Qualification Year 1. Nigerian Law School, BL-Barrister-at– Law. December, Lagos. 1990 2. University of Cross River L.L.B(Hons) September, State (now University of 1989 Uyo) 3. School of Arts and WAEC (A/Level) June, 1984 Science, Uyo 4. Secondary School, Adim WAEC (O/Level) June, 1982 5. Primary School, Adim FSLC July, 1976 CAREER PROGRESSION 1. As Litigation Officer (NYSC) Nnewi Local Government Area – Oct, 1990 – Sept, 1991 Headquarters, Nnewi Anambra State. 2. As Barrister and Solicitor Chief Richard Efa & Co – Dec, 1991 – Dec, 1992 53, Edgerly Road Calabar. 3. Barrister and Solicitor Kanu G. Agabi(CON), SAN & Associates – Jan, 1993 – June, 1995 No. 1, Edet Eyo Crescent Calabar. -

2017-2018 Nov. Set Nominal Roll Verification

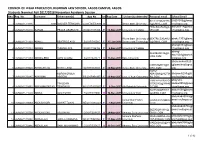

COUNCIL OF LEGAL EDUCATION, NIGERIAN LAW SCHOOL, LAGOS CAMPUS, LAGOS. Students Nominal Roll 2017/2018 November Academic Session . SNo Reg. No. Surname Othername(s) App No Sex Reg Date University Attended Personal email School Email SILVERHOUGH36 68091036@lawsc 1 LA/NOV/17/1036 6809 DSILVER TERKUMA G/2017S/576809 M Benue State University [email protected] hoollagos.org PEACEAARON@LI aaron0318@laws 2 LA/NOV/17/0318 AARON PEACE OSARUCHI W/2017/417985 F 10-Nov-2017 University of Calabar VE.COM choollagos.org Rivers State University of BEATRICEABAKU abaku1303@laws 3 LA/NOV/17/1303 ABAKU BEATRICE AYO S/2017/740585 F 15-Jan-2018 Science and Technology [email protected] choollagos.org abang0133@laws 4 LA/NOV/17/0133 ABANG THELMA AYA W/2017/496452 F 9-Nov-2017 University of Calabar choollagos.org abang- ALEXBANG10@G ebu1039@lawsch MAIL.COM 5 LA/NOV/17/1039 ABANG-EBU ALEX OJONG A/2017/623571 M 13-Dec-2017 Baze University oollagos.org abanumebo0520 MARYZION19@G @lawschoollagos. 6 LA/NOV/17/0520 ABANUMEBO MARY EJIRO G/2017/268984 F 14-Nov-2017 Benue State University MAIL.COM org KOFO- KOFOWOROLA ABAYOMI@HOTM abayomi0285@la 7 LA/NOV/17/0285 ABAYOMI ABIDEMI FS/2017/401997 F 10-Nov-2017 Univ. of Kent Canterbury AIL.COM wschoollagos.org TIMILEHINABAYO abayomi- TIMILEHIN MISADIKU@YAHO sadiku0952@laws 8 LA/NOV/17/0952 ABAYOMI-SADIKU TEMIDAYO AU/2017/997667 F 8-Dec-2017 Afe Babalola University O.COM choollagos.org TOYINSMARTIST abdul1068@lawsc 9 LA/NOV/17/1068 ABDUL ALIU TOYIN Y/2017/437890 M 14-Dec-2017 University of Ilorin @GMAIL.COM hoollagos.org abdulkadir0059@l