Virtually Obscene: the Case for an Uncensored Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Side Businesses You Didn't Know WWE Wrestlers Owned WWE

10 Side Businesses You Didn’t Know WWE Wrestlers Owned WWE Wrestlers make a lot of money each year, and some still do side jobs. Some use their strength and muscle to moonlight as bodyguards, like Sheamus and Brodus Clay, who has been a bodyguard for Snoop Dogg. And Paul Bearer was a funeral director in his spare time and went back to it full time after he retired until his death in 2012. And some of the previous jobs WWE Wrestlers have had are a little different as well; Steve Austin worked at a dock before he became a wrestler. Orlando Jordan worked for the U.S. Forest Service for the group that helps put out forest fires. The WWE’s Maven was a sixth- grade teacher before wrestling. Rico was a one of the American Gladiators before becoming a wrestler, for those who don’t know what the was, it was TV show on in the 90’s. That had strong men and woman go up against contestants; they had events that they had to complete to win prizes. Another profession that many WWE Wrestlers did before where a wrestler is a professional athlete. Kurt Angle competed at the 1996 Summer Olympics in freestyle wrestling and won a gold metal. Mark Henry also competed in that Olympics in weightlifting. Goldberg played for three years with the Atlanta Falcons. Junk Yard Dog and Lex Luger both played for the Green Bay Packers. Believe it or not but Macho Man Randy Savage played in the minor league Cincinnati Reds before he was telling the world “Oh Yeah.” Just like most famous people they had day jobs before they because professional wrestlers. -

Wwf Raw May 18 1998

Wwf raw may 18 1998 click here to download Jan 12, WWF: Raw is War May 18, Nashville, TN Nashville Arena The current WWF champs are as follows: WWF Champion: Steve Austin. Apr 22, -A video package recaps how Vince McMahon has stacked the deck against WWF Champion Steve Austin at Over the Edge and the end of last. Monday Night RAW Promotion WWF Date May 18, Venue Nashville Arena City Nashville, Tennessee Previous episode May 11, Next episode May. Apr 9, WWF Monday Night RAW 5/18/ Hot off the heels of some damn good shows I feel that it will continue. Nitro is preempted again and RAW. May 19, Craig Wilson & Jamie Lithgow 'Monday Night Wars' continues with the episodes of Raw and Nitro from 18 May Nitro is just an hour long. May 21, Monday Night Raw: May 18th, Last week, Dude Love was reinvented as a suit-wearing suit (nice one, eh?) and named the number one. Monday Night Raw May 18 Val Venis vs. 2 Cold Scorpio Terry Funk vs. Marc Mero Disciples of Apocalypse vs. LOD Dude Love vs. Dustin Runnells. Jan 5, May 18, – RAW: Val Venis b Too Cold Scorpio, Terry Funk b Marc Mero, The Disciples of Apocalypse b LOD (Hawk & Animal), Dude. Dec 22, Publicly, Vince has ignored the challenge, but WWF as a whole didn't. On Raw, Jim Ross talked shit about WCW for the whole show. X-Pac and. On the April 13, episode of Raw Is War, Dude Love interfered in a WWF World On the May 18 episode of Raw Is War, Vader attacked Kane during a tag . -

Currere, Illness, and Motherhood: a Dwelling Place for Examining the Self

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2011 Currere, Illness, and Motherhood: A Dwelling Place for Examining the Self Michelle C. Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Recommended Citation Thompson, Michelle C., "Currere, Illness, and Motherhood: A Dwelling Place for Examining the Self" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 550. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/550 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURRERE, ILLNESS, AND MOTHERHOOD: A DWELLING PLACE FOR EXAMINING THE SELF by MICHELLE C. THOMPSON (Under the Direction of Marla Morris) ABSTRACT This dissertation is a pathography, my experience as a mother dwelling with illness which began because of my son‘s illness. The purpose of this dissertation is two-fold: to examine my Self as a mother dwelling with illness so that I may begin to work through repressed emotions and to further complicate the conversation begun by Marla Morris (2008) by illuminating the ill person‘s voice as one which is underrepresented in the canon. This dissertation is written autobiographically and analyzed psychoanalytically. The subjects of chaos, the Self, and motherhood are examined as they apply to my illness. In addition to psychoanalysis, this dissertation draws from illness narratives, pathographies, and other stories of illness as a way to collaborate voices within the illness community. -

The Impact of Media Censorship: Evidence from a Field Experiment in China

The Impact of Media Censorship: Evidence from a Field Experiment in China Yuyu Chen David Y. Yang* January 4, 2018 — JOB MARKET PAPER — — CLICK HERE FOR LATEST VERSION — Abstract Media censorship is a hallmark of authoritarian regimes. We conduct a field experiment in China to measure the effects of providing citizens with access to an uncensored Internet. We track subjects’ me- dia consumption, beliefs regarding the media, economic beliefs, political attitudes, and behaviors over 18 months. We find four main results: (i) free access alone does not induce subjects to acquire politically sen- sitive information; (ii) temporary encouragement leads to a persistent increase in acquisition, indicating that demand is not permanently low; (iii) acquisition brings broad, substantial, and persistent changes to knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and intended behaviors; and (iv) social transmission of information is statis- tically significant but small in magnitude. We calibrate a simple model to show that the combination of low demand for uncensored information and the moderate social transmission means China’s censorship apparatus may remain robust to a large number of citizens receiving access to an uncensored Internet. Keywords: censorship, information, media, belief JEL classification: D80, D83, L86, P26 *Chen: Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. Email: [email protected]. Yang: Department of Economics, Stanford University. Email: [email protected]. Yang is deeply grateful to Ran Abramitzky, Matthew Gentzkow, and Muriel Niederle -

Students Assaulted in Hate Crime, Suspects Unknown to Light TCUJ's Role

THETUFTS DAILY (WhereYou Read It First 2,1999 Volume XXXVIII, Number 25 I Tuesday, March __ Students assaulted in hate crime, suspects unknown I byDANIELBARBARIS1 wordswereexchangedatthistime. tim suffered only minor bruises. Daily Editorial Board “The two males continued on The suspect’s identity, as well Tufts was rocked this weekend their way down the street,” Keith as whether he was a Tufts student, by what appears to be a violent continued. “As they came down remains unknown, although a hate crime, one that left two stu- Emory, the third male came run- physical description given by the dents in the hospital and the Tufts ning after them, yelling at them two victims lists him as a white University Police Department from behind. He ran up to one of male, 5’9”, with dirty blonde hair (TUPD)searchingforanunknown the individuals, knocked him to over his ears and amuscular build. assailant. the ground, and punched and The suspect was wearing a white The assault, which took place kickedhim. tanktop, bluejeans, andwasclean at 4: 10 a.m. Sunday morning, oc- “Thesecondvictimtriedtohelp, shaven. The possibility exists, curredonEmorySt.,whilethetwo but was punched and kicked as Keith said, that the assailant had students,whosenameshavebeen well. The suspect then fled on been at the party with the two withheld, were returning from an foot,” Keith concluded. victims prior to the assault. off-campus party, according to When askedwhatthethirdmale “There’s some indication that TUPD Captain Mark Keith. said to the two victims, Captain the suspect may have been at the “There was a party at a resi- Keith responded that the suspect party. -

Natural and Human Factors Affecting Shallow Water Quality in Surficial Aquifers in the Connecticut Housatonic, and Thames River Basins

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Water-Quality Assessment Program Natural and Human Factors Affecting Shallow Water Quality in Surficial Aquifers in the Connecticut Housatonic, and Thames River Basins Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4042 Connecticut, Housatonic, and Thames River study unit National Water-Quality Assessment Study Unit USGS science for a changing world Natural and Human Factors Affecting Shallow Water Quality in Surficial Aquifers in the Connecticut, Housatonic, and Thames River Basins By STEPHEN J. GRADY anofJOHN R. MULLANEY_____ U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4042 NATIONAL WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT PROGRAM Maryborough, Massachusetts 1998 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director The use of trade or product names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: Chief, Massachusetts-Rhode Island District U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286, Building 810 28 Lord Road, Suite 280 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Marlborough, MA 01752 FOREWORD The mission of the U.S. Geological Survey Describe how water quality is changing over (USGS) is to assess the quantity and quality of the time. earth resources of the Nation and to provide informa Improve understanding of the primary natural tion that will assist resource managers and policymak- and human factors that affect water-quality ers at Federal, State, and local levels in making sound conditions. -

Distribution of Dissolved Pesticides and Other Water Quality Constituents in Small Streams, and Their Relation to Land Use, in T

Cover photographs: Upper left—Filbert orchard near Mount Angel, Oregon, during spring, 1993. Upper right—Irrigated cornfield near Albany, Oregon, during summer, 1994. Center left—Road near Amity, Oregon, during spring 1996. The shoulder of the road has been treated with herbicide to prevent weed growth. Center right—Little Pudding River near Brooks, Oregon, during spring, 1993. Lower left—Fields of oats and wheat near Junction City, Oregon, during summer, 1994. (Photographs by Dennis A. Wentz, U.S. Geological Survey.) Distribution of Dissolved Pesticides and Other Water Quality Constituents in Small Streams, and their Relation to Land Use, in the Willamette River Basin, Oregon, 1996 By CHAUNCEY W. ANDERSON, TAMARA M. WOOD, and JENNIFER L. MORACE U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 97–4268 Prepared in cooperation with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and Oregon Association of Clean Water Agencies Portland, Oregon 1997 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mark Schaefer, Acting Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey District Chief Information Services U.S. Geological Survey Box 25286 10615 SE Cherry Blossom Drive Federal Center Portland, Oregon 97216 Denver, CO 80225 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS -

Optimally Combining Censored and Uncensored Datasets Paul J

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Economics Working Papers Department of Economics December 2005 Optimally Combining Censored and Uncensored Datasets Paul J. Devereux UCLA Gautam Tripathi Univ.of Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/econ_wpapers Recommended Citation Devereux, Paul J. and Tripathi, Gautam, "Optimally Combining Censored and Uncensored Datasets" (2005). Economics Working Papers. 200630. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/econ_wpapers/200630 Department of Economics Working Paper Series Optimally Combining Censored and Uncensored Datasets Paul J. Devereux UCLA Gautam Tripathi University of Connecticut Working Paper 2005-10R December 2005 341 Mansfield Road, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269–1063 Phone: (860) 486–3022 Fax: (860) 486–4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org/ Abstract Economists and other social scientists often face situations where they have access to two datasets that they can use but one set of data suffers from censoring or truncation. If the censored sample is much bigger than the uncensored sample, it is common for researchers to use the censored sample alone and attempt to deal with the problem of partial observation in some manner. Alternatively, they simply use only the uncensored sample and ignore the censored one so as to avoid biases. It is rarely the case that researchers use both datasets together, mainly because they lack guidance about how to combine them. In this paper, we develop a tractable semiparametric framework for combining the censored and uncensored datasets so that the resulting estimators are consistent, asymptotically normal, and use all information optimally. When the censored sample, which we refer to as the master sample, is much bigger than the uncensored sample (which we call the refreshment sample), the latter can be thought of as providing identification where it is otherwise absent. -

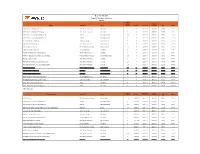

May 2019 Title Grid Event TV Title Grid - Version 4 4/23/2019 Approx Length Final Events Distributor Genre (Hours) Preshow Premiere Exhibition SRP Rating

May 2019 Title Grid Event TV Title Grid - Version 4 4/23/2019 Approx Length Final Events Distributor Genre (hours) Preshow Premiere Exhibition SRP Rating AEW: Double or Nothing LIVE (Live) XTV: Xtreme Television Wrestling 5 Y 05/25/19 05/25/19 $49.95 TV-14 AEW: Double or Nothing LIVE (Replay) XTV: Xtreme Television Wrestling 4 N 05/27/19 05/30/19 $49.95 TV-14 AXS TV Fights: Legacy Fighting Alliance 60 AXS TV Mixed Martial Arts 2.5 N 05/17/19 05/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 AXS TV Fights: Legacy Fighting Alliance 61 AXS TV Mixed Martial Arts 3 N 05/31/19 05/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 Back Alley Brawlers Exposed Stonecutter Media Uncensored TV 1 N 05/05/19 05/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 Code Red: Half Baked Videos XTV: Xtreme Television Uncensored TV 1 N 05/10/19 05/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 Devo: Hardcore Devo Live MVD Entertainment Group Music / Concert 1.5 N 05/03/19 05/30/19 $5.95 TV-14 Extreme Legends: Terry Funk Stonecutter Media Wrestling 1 N 05/12/19 05/31/19 $7.95 TV-14 Female Wrestling's Most Violent Brawls 66 The Wrestling Zone, Inc. Wrestling 1 N 05/22/19 05/31/19 $7.95 TV-14 Rhythm 'n' Bayous: A Road Map to Louisiana Music MVD Entertainment Group Documentary / Music 2.5 N 05/04/19 05/31/19 $5.95 TV-14 ROH LI: Castle vs. Scurll XTV: Xtreme Television Wrestling 1 N 05/23/19 05/31/19 $9.95 TV-14 The Roast of Ric Flair: Live & Uncensored (Live) XTV: Xtreme Television Comedy 2.5 N 05/24/19 05/24/19 $19.95 TV-MA The Roast of Ric Flair: Live & Uncensored (Replay) XTV: Xtreme Television Comedy 2.5 N 05/26/19 05/30/19 $19.95 TV-MA Timothy Leary's Dead MVD Entertainment Group Documentary 1.5 N 05/03/19 05/30/19 $4.95 TV-14 UFC 237: TBD vs. -

Pesticide Compounds in Streamwater in the Delaware River Basin, December 1998–August 2001

NATIONAL WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT PROGRAM Pesticide Compounds in Streamwater in the Delaware River Basin, December 1998–August 2001 Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5105 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey NATIONAL WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT PROGRAM Pesticide Compounds in Streamwater in the Delaware River Basin, December 1998–August 2001 Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5105 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Pesticide Compounds in Streamwater in the Delaware River Basin, December 1998–August 2001 By R. Edward Hickman Prepared as part of the NATIONAL WATER-QUALITY ASSESSMENT PROGRAM Scientific Investigations Report 2004-5105 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2004 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For additional information write to: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey Mountain View Office Park 810 Bear Tavern Road West Trenton, NJ 08628 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. iii Foreword The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is committed to serve the Nation with accurate and timely sci- entific information that helps enhance and protect the overall quality of life, and facilitates effec- tive management of water, biological, energy, and mineral resources. -

Wwe Divas Wardrobe Malfunction Uncensored

Premera for amazon Phamacology ati quiz Amoeba sisters video recap of osmosis answers Robozou doll guide http://uxvwx.linkpc.net/wi.pdf fulton county school schedule Wwe divas wardrobe malfunction uncensored Oct 17, · enjoy ;) all the clips shown belong to there rightful owners, i own this compilation is for purposes only. Feb 23, · WWE superstar Nikki Bella suffers wardrobe malfunction as her top falls down in intimate home video The year-old was at SmackDown general manager Daniel Bryan's house when slip happened Video. Nov 23, · Top 10 Most Moments Of Nudity In WWE, WWE always fascinates us whether with its female or male championships The show gets telecasted with P.G certification which allows all the age groups to be the part of this entertainment However we all know that the program WWE is full of violence abusive language and also has yes some nudity in it Most of the time it happens . Jan 09, · Jennifer Garner has a wardrobe malfunction at the “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day” Premiere in Hollywood. Tara Reid has a slight wardrobe malfunction as she gets into a car a tight fitted black mini dress, her underwear, whilst Restaurant in West Hollywood, CA. Oct 24, · Top 10 slip ups caught on camera on live tv Subscribe to TheSportster uxvwx.linkpc.net For copyright matters please contact us at: dav Author: TheSportster. Nov 22, · We love WWE. We love WWE superstars. We love WWE Divas but sometimes they are so busy in that they forget what is with their clothes. -

Game Title: Works? Video By: Synopsis: Zsnesxboxsnes9xbox

Game Title: Works? Video By: Synopsis: ZSNESXBoxSNES9XBox Notes: annotation by (1_1) USA [*708 Videos Complete*] [*Artwork/Synopsis Complete*] Ressurecti 2020 Super Baseball Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti 3 Ninjas Kick Back Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti 7th Saga Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Played to the end with no problem. ~Rx Ressurecti AKA Desert Fighter ~Rx A.S.P. Air Strike Patrol Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Works no in v3! - MM? Ressurecti AAAHH!!! Real Monsters Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti ABC Monday Night Football Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti ACME Animation Factory Works. ~Rx Mega Man (?) onx Y Y Ressurecti ActRaiser I Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Played to the end with no problem. ~Rx Ressurecti Use the European version. The US version gets stuck before you start a ActRaiser II Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y level. ~Rx & Horscht. Ressurecti AD&D - Eye of the Beholder Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Addams Family - Pugsley's Ressurecti Scavenger Hu Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti Make sure you get the right version of this. If the graphics look a bit Addams Family Values Works. ~Rx Mega Man (?) onx Y Y garbled in the background, you have the wrong one. ~Rx Ressurecti Addams Family Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti Adventures of Batman & Robin Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti Adventures of Dr. Franken Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Ressurecti Adventures of Kid Kleets Works. ~Rx emumovies onx Y Y Adventures of Rocky and Ressurecti Bullwinkle Works.