The Big Lebowski (1998) and No Country for Old Men (2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Movies and Movie Clips

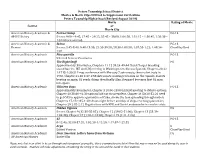

Peters Township School District Movies & Movie Clips Utilized to Supplement Curriculum Peters Township High School (Revised August 2019) Movie Rating of Movie Course or Movie Clip American History Academic & Forrest Gump PG-13 AP US History Scenes 9:00 – 9:45, 27:45 – 29:25, 35:45 – 38:00, 1:06:50, 1:31:15 – 1:30:45, 1:50:30 – 1:51:00 are omitted. American History Academic & Selma PG-13 Honors Scenes 3:45-8:40; 9:40-13:30; 25:50-39:50; 58:30-1:00:50; 1:07:50-1:22; 1:48:54- ClearPlayUsed 2:01 American History Academic Pleasantville PG-13 Selected Scenes 25 minutes American History Academic The Right Stuff PG Approximately 30 minutes, Chapters 11-12 39:24-49:44 Chuck Yeager breaking sound barrier, IKE and LBJ meeting in Washington to discuss Sputnik, Chapters 20-22 1:1715-1:30:51 Press conference with Mercury 7 astronauts, then rocket tests in 1960, Chapter 24-30 1:37-1:58 Astronauts wanting revisions on the capsule, Soviets beating us again, US sends chimp then finally Alan Sheppard becomes first US man into space American History Academic Thirteen Days PG-13 Approximately 30 minutes, Chapter 3 10:00-13:00 EXCOM meeting to debate options, Chapter 10 38:00-41:30 options laid out for president, Chapter 14 50:20-52:20 need to get OAS to approve quarantine of Cuba, shows the fear spreading through nation, Chapters 17-18 1:05-1:20 shows night before and day of ships reaching quarantine, Chapter 29 2:05-2:12 Negotiations with RFK and Soviet ambassador to resolve crisis American History Academic Hidden Figures PG Scenes Chapter 9 (32:38-35:05); -

Hole a Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers

University of Dundee DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Going Down the 'Wabbit' Hole A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Barrie, Gregg Award date: 2020 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Gregg Barrie PhD Film Studies Thesis University of Dundee February 2021 Word Count – 99,996 Words 1 Going Down the ‘Wabbit’ Hole: A Remediative Approach to the Filmmaking of the Coen Brothers Table of Contents Table of Figures ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Declaration ............................................................................................................................................ -

A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Honors Scholar Theses Honors Scholar Program Spring 5-6-2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Timothy Semenza University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Semenza, Timothy, ""The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen" (2012). Honors Scholar Theses. 241. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/srhonors_theses/241 Semenza 1 Timothy Semenza "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Semenza 2 Timothy Semenza Professor Schlund-Vials Honors Thesis May 2012 "The wicked flee when none pursueth": A Formalist Critique of Three Crime Films by Joel and Ethan Coen Preface Choosing a topic for a long paper like this can be—and was—a daunting task. The possibilities shot up out of the ground from before me like Milton's Pandemonium from the soil of hell. Of course, this assignment ultimately turned out to be much less intimidating and filled with demons than that, but at the time, it felt as though it would be. When you're an English major like I am, your choices are simultaneously extremely numerous and severely restricted, mostly by my inability to write convincingly or sufficiently about most topics. However, after much deliberation and agonizing, I realized that something I am good at is writing about film. -

The Humorous View of a Psychotic Break in Raising Arizona, by the Coen Brothers

The Humorous View of a Psychotic Break in Raising Arizona, by the Coen Brothers Thoughts on the bizarre object. Robert A.W. Northey Raising Arizona, the second film by the now well known writer/director duo, Joel and Ethan Coen, was released in 1987. Many of the actors in the film were relatively unknown at the time. The young Nicolas Cage had just caught attention starring beside Cher in Moonstruck, with a few smaller roles in some feature films before that. Holly Hunter was relatively unknown. Frances McDormand had recognition for her stage acting with one Tony nomination, otherwise a few television series and one feature film, Blood Simple, the first Coen brothers film (know that she is married to Joel Coen). John Goodman had been in a few films, but his fame from the TV series Rosanne was still ahead of him. Raising Arizona is a film I know well, first seeing it shortly after it was released, and having re- watched it at least a dozen times since then. The quirky comedy speaks to my sense of humour, and it was an early lesson to me about the art of making film, and of telling a story. Reviewing it more recently from a psychoanalytic perspective has brought me great joy as I was able to discover yet more in this film that I love. Could this story be told in any other way than a comedy? Certainly a story of a childless couple, devastated by their inability to have a child, kidnapping a baby to try and fill the need, hiding the crime from inquiring friends, and being hunted by police and bounty hunters, might be possible as a drama; but would it be watchable or relatable or on any level believable? I would suggest that the story as a comedy nullifies believability as a concern. -

Elijah Siegler, Coen. Framing Religion in Amoral Order Baylor University Press, 2016

Christian Wessely Elijah Siegler, Coen. Framing Religion in Amoral Order Baylor University Press, 2016 I would hardly seem the most likely candidate to review a book on the Coen brothers. I have not seen all of their films, and the ones I saw … well, either I did not understand them or they are really as shallow as I thought them to be. With one exception: I did enjoy O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000). And I like A Serious Man (2009). So, two exceptions. And, of course, True Grit (2010) – so, all in all three exceptions1 … come to think of it, there are more that have stuck in my mind in a positive way, obfuscated by Barton Fink (1991) or Burn After Reading (2008). Therefore, I was curious wheth- er Elijah Siegler’s edited collection would change my view on the Coens. Having goog- led for existing reviews of the book that might inspire me, I discovered that none are to be found online, apart from the usual flattery in four lines on the website of Baylor University Press, mostly phrases about the unrivalled quality of Siegler’s book. Turns out I have do all the work by myself. Given that I am not familiar with some of the films used to exemplify some of this book’s theses, I will be brief on some chapters and give more space to those that deal with the films I know. FORMAL ASPECTS Baylor University Press is well established in the fields of philosophy, religion, theol- ogy, and sociology. So far, they have scarcely published in the media field, although personally I found two of their books (Sacred Space, by Douglas E. -

Cross-Evaluation of Metrics to Estimate the Significance of Creative Works

Cross-evaluation of metrics to estimate the significance of creative works Max Wassermana, Xiao Han T. Zengb, and Luís A. Nunes Amaralb,c,d,e,1 Departments of aEngineering Sciences and Applied Mathematics, bChemical and Biological Engineering, and cPhysics and Astronomy, dHoward Hughes Medical Institute, and eNorthwestern Institute on Complex Systems, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 Edited by Kenneth W. Wachter, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved December 1, 2014 (received for review June 27, 2014) In a world overflowing with creative works, it is useful to be able a more nuanced estimation of significance, it is also more diffi- to filter out the unimportant works so that the significant ones cult to measure. For example, Ingmar Bergman’s influence on can be identified and thereby absorbed. An automated method later film directors is undebatable (4, 5), but not easily quanti- could provide an objective approach for evaluating the significance fied. Despite different strengths and limitations, any quantitative of works on a universal scale. However, there have been few approaches that result in an adequate estimation of significance attempts at creating such a measure, and there are few “ground should be strongly correlated when evaluated over a large corpus truths” for validating the effectiveness of potential metrics for sig- of creative works. nificance. For movies, the US Library of Congress’s National Film By definition, the latent variable for a creative work is in- “ accessible. However, for the medium of films—which will be the Registry (NFR) contains American films that are culturally, histori- — cally, or aesthetically significant” as chosen through a careful focus of this work there is in fact as close to a measurement of the latent variable as one could hope for. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

Il Cinema Dei Fratelli Coen: Declinazioni Del Vuoto 1

Il cinema dei fratelli Coen: declinazioni del vuoto Introduzione Joel e Ethan Coen esordiscono come registi negli anni Ottanta, epoca in cui è lo stesso concetto di autore – e quindi anche quello di regista – a tornare di moda, ma al tempo stesso si trasforma: l’artista non è più creatore, ma imitatore, in un momento storico in cui si riconosce di non aver più nulla da dire. Come infatti sottolinea Buccheri, “non cerca una voce personale, ma uno stile che gli dia visibilità, un’estetica come marchio e come look – si mette in scena, offrendo il proprio corpo allo “scandalo evangelico”, in una deriva dell’autobiografismo politico degli anni Sessanta”1. E in questo giudizio di valore sono coinvolti anche i fratelli Coen che, come Brian De Palma, o Woody Allen, sono spesso stati definiti manieristi; termine inteso in questo contesto come imitatori prima che della natura, di altro cinema a sé precedente. Tuttavia, nonostante critici come Paolo Cerchi Usai abbia riportato, su “Segnocinema”, come “il loro cinema sia senza motivo, ma abbiano deciso di fare ugualmente cinema nel nome della sua inutilità”2, l’attitudine dei due registi è in realtà profondamente critica riguardo al materiale usato: dietro all’apparenza leggera infatti, si nasconde una critica radicale agli stereotipi e simboli della vita americana e in generale alla vita contemporanea, come il consumismo, la ristrettezza mentale della provincia, la ruralità, la libertà dell’arte, la controcultura stessa. I personaggi che portano in scena hanno corpi sgraziati, spesso grotteschi (si pensi a quelli interpretati da Steve Buscemi, uno degli attori feticcio del cinema dei due fratelli), e sono destinati ad un’irrimediabile alienazione, che arriva a distruggerli, persi nelle rete delle rappresentazioni e leggi sociali. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Et Tu, Dude? Humor and Philosophy in the Movies of Joel And

ET TU, DUDE? HUMOR AND PHILOSOPHY IN THE MOVIES OF JOEL AND ETHAN COEN A Report of a Senior Study by Geoffrey Bokuniewicz Major: Writing/Communication Maryville College Spring, 2014 Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Faculty Supervisor Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Division Chair Abstract This is a two-part senior thesis revolving around the works of the film writer/directors Joel and Ethan Coen. The first seven chapters deal with the humor and philosophy of the Coens according to formal theories of humor and deep explication of their cross-film themes. Though references are made to most of their films in the study, the five films studied most in-depth are Fargo, The Big Lebowski, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, and A Serious Man. The study looks at common structures across both the Coens’ comedies and dramas and also how certain techniques make people laugh. Above all, this is a study on the production of humor through the lens of two very funny writers. This is also a launching pad for a prospective creative screenplay, and that is the focus of Chapter 8. In that chapter, there is a full treatment of a planned script as well as a significant portion of written script up until the first major plot point. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter - Introduction VII I The Pattern Recognition Theory of Humor in Burn After Reading 1 Explanation and Examples 1 Efficacy and How It Could Help Me 12 II Benign Violation Theory in The Big Lebowski and 16 No Country for Old Men Explanation and Examples -

Smart Cinema As Trans-Generic Mode: a Study of Industrial Transgression and Assimilation 1990-2005

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service Smart cinema as trans-generic mode: a study of industrial transgression and assimilation 1990-2005 Laura Canning B.A., M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. November 2013 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Pat Brereton 1 I hereby certify that that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 58118276 Date: ________________ 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction p.6 Chapter Two: Literature Review p.27 Chapter Three: The industrial history of Smart cinema p.53 Chapter Four: Smart cinema, the auteur as commodity, and cult film p.82 Chapter Five: The Smart film, prestige, and ‘indie’ culture p.105 Chapter Six: Smart cinema and industrial categorisations p.137 Chapter Seven: ‘Double Coding’ and the Smart canon p.159 Chapter Eight: Smart inside and outside the system – two case studies p.210 Chapter Nine: Conclusions p.236 References and Bibliography p.259 3 Abstract Following from Sconce’s “Irony, nihilism, and the new American ‘smart’ film”, describing an American school of filmmaking that “survives (and at times thrives) at the symbolic and material intersection of ‘Hollywood’, the ‘indie’ scene and the vestiges of what cinephiles used to call ‘art films’” (Sconce, 2002, 351), I seek to link industrial and textual studies in order to explore Smart cinema as a transgeneric mode. -

She's Baa-Aack!

FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 17, 2018 5:15:56 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of March 25 - 31, 2018 She’s Roseanne Barr stars in baa-aack! “Roseanne” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Roseanne (Roseanne Barr, “The Roseanne Barr Show”) and Dan Conner (John Goodman, “The Big Lebowski, 1998”) return to the airwaves in the premiere of “Roseanne,” airing Tuesday, March 27, on ABC. A reboot of the classic comedy of the same name, the new series once again takes a look at the struggles of working class Americans. The rest of the original main cast returns as well, including Emmy winner Laurie Metcalf (“Lady Bird,” 2017). WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL Salem, NH • Derry, NH • Hampstead, NH • Hooksett, NH ✦ 37 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE Newburyport, MA • North Andover, MA • Lowell, MA ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIES YOUR MEDICAL HOME FOR CHRONIC ASTHMA We Need: SALES & SERVICE SPRING ALLERGIES ARE HERE! Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE DON’T LET IT GET YOU DOWN INSPECTIONS Alleviate your mold allergy this season! We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC Appointments Available Now CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 978-683-4299 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA www.newenglandallergy.com at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Thomas F. Johnson, MD, FACP, FAAAAI, FACAAI Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Mar 17, 2018 5:15:57 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights CHANNEL Kingston (27) Atkinson Sunday 9:30 p.m.