Cleveland's Leading Downtown Department Stores: a Business Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

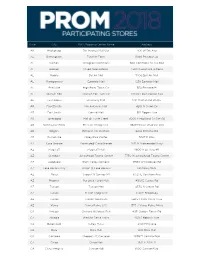

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

\ in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York

\ IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK COVER SHEET: APPLICATION FOR PROFESSIONAL COMPENSATION --------------------------------------------------------------) ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) Bradlees Stores, Inc., et al. ) Case Nos 95 B 42777 through ) 95B 42784 Debtors ) (Judge Burton R. Lifland) ) --------------------------------------------------------------) Jointly Administered Type of Application: Interim Final X ' Name of Applicant: Zolfo Cooper, LLC Authorized to Provide Professional Services to: The Debtors Date of Order Authorizing Employment: August 23, 1995 Compensation Sought: Application Date: March 19, 1999 Application Period: June 23, 1995 - February 2, 1999 Hours Amount . Fees: Professional 20,270.3 $5,530,799.00 Expense Reimbursement 491,944.14 Total $6,022,743.14 1 Fees incurred during the period from June 23, 1995 through February 2, 1999 (the “Application Period”) A summary of professional fees incurred during the Application Period, by professional, is set forth below: Name of Position Years of Hours Hourly Professional with ZC Experience Billed Rate Total Partners: S. Cooper Principal 28 7.6 $425 $3,230.00 S. Cooper 1,839.6 $395 726,642.00 S. Cooper 513.4 $375 192,525.00 D. Taura Principal 34 52.3 $375 19,612.50 M. Flynn Principal 20 2.0 $375 750.00 M. Flynn 10.0 $350 3,500.00 N. Lavin Principal 32 2.9 $395 1,145.50 N. Lavin 14.7 $375 5,512.50 N. Lavin 44.6 $350 15,610.00 N. Lavin 15.6 $325 5,070.00 Associates: P. Gund Project Manager 15 140.0 $375 52,500.00 P. Gund 1,928.8 $325 626,860.00 P. -

031100Travelguide.Pdf

DOWNTOWN CLEVELAND (10 min. from The Cleveland Clinic) DOWNTOWN CLEVELAND (10 min. from The Cleveland Clinic) Fine Dining Points of Interest Hyde Park Chop House Cleveland Browns Stadium (Browns -NFL) Jacobs Field (Indians-MLB) 123 Prospect Ave 216-344-2444 Great Lakes Science Center The Warehouse District Johnny's Downtown 1406 W. 6th St 216-623-0055 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame & Museum The Flats on the Cuyahoga River Morton's of Chicago Steakhouse, Tower City Center Steamship William G. Mather Museum Playhouse Square Theatres 1600 W. 2nd St 216-621-6200 The COD, World War II Submarine Tower City Center One Walnut The Cleveland Convention Center The Galleria at Erieview 1 Walnut Ave 216-575-1111 The Old Stone Church Public Square Casual Dining Gund Arena (Cavaliers-NBA) Fat Fish Blue 21 Prospect Ave 216-875-6000 Flannery's Pub of Cleveland 323 Prospect St 216-781-7782 Frank & Pauly's, BP Building 200 Public Square 216-575-1000 Hard Rock Café, Tower City Center 230 W. Huron Rd 216-830-7625 Hornblower's Barge & Grill 1151 N. Marginal Rd 216-363-1151 John Q's Steakhouse 55 Public Square 216-861-0900 Ruthie & Moe's Diner 4002 Prospect Ave 216-881-6637 Slyman's Deli 3106 St. Clair Ave 216-621-3760 Accommodations Short Stay Comfort Inn $ 216-861-0001 1800 Euclid Ave 800-424-6423 Embassy Suites Hotel $$$ 216-523-8000 1701 E. 12th St 800-362-2779 Hampton Inn $ 216-241-6600 1460 E. 9th St 800-426-7866 Holiday Inn Lakeside Express $ 216-443-1000 629 Euclid Ave 800-465-4329 Holiday Inn City Center $ 216-241-5100 Accommodations Extended Stay 1111 Lakeside Ave 800-465-4329 The following provide various extended stay options which include Hyatt Regency $$$$ 216-575-1234 apartments, condominiums, private homes and bed and breakfasts. -

By Joseph Aquino December 17, 2019 - New York City

New York’s changing department store landscape - by Joseph Aquino December 17, 2019 - New York City Department stores come and go. When one goes out of business, it’s nothing unusual. But consider how many have gone out of business in New York City in just the past generation: Gimbels, B. Altman, Mays, E. J. Korvette, Alexanders, Abraham & Straus, Gallerie Lafayette, Wanamaker, Sears & Roebuck, Lord & Taylor, Bonwit Teller, and now Barneys New York—and those are just the ones I remember. The long-time survivors are Bloomingdale’s, Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf Goodman and Macy’s. The new kids on the block are Nordstrom (which has had a chance to study their customer since they have operated Nordstrom Rack for some time) and Neiman-Marcus, which has opened at Hudson Yards with three levels of glitz, glam, luxury, and fancy restaurants. It’s unfortunate to see Lord & Taylor go, especially to be taken over by a group like WeWork, which has been on a meteoric rise to the top of the heap and controls a lot of office space. I was disappointed at this turn of events but I understood it, and was not surprised. Lord & Taylor had the best ladies’ department (especially for dresses) in Manhattan. I know, because I try to be a good husband, so I shop with my wife a lot! But that was a huge amount of space for the company to try to hold onto. Neither does the closing of Barneys comes as any shock. I frequented Fred’s Restaurant often and that was the place to see and be seen. -

Draft Submission to the United Kingdom's Department of Health the European Commission's Proposal for a Revised Tobacco Prod

DRAFT SUBMISSION TO THE UNITED KINGDOM’S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION’S PROPOSAL FOR A REVISED TOBACCO PRODUCTS DIRECTIVE 1. Introduction i. British American Tobacco UK Ltd and the scope of this submission British American Tobacco UK Ltd (BAT UK) is the British operating subsidiary of British American Tobacco Plc. The UK company is run from its offices in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire and employs some 170 people nationwide. British American Tobacco UK Ltd is the UKs third largest tobacco company with a share of the legal UK market of just over 8%. Its main brands are Pall Mall, Rothmans, Royals, Lucky Strike, Vogue, Dunhill and Cutters Choice. Through this document, BAT UK submits its initial viewpoints on the European Commission’s proposal for a revised Tobacco Products Directive (“The Directive”), launched on 19 December 2012. The proposal is now the subject of the EU’s ordinary legislative procedure in the context of which Member States Governments including the UK will form negotiating positions to be progressed in the Council of Ministers. This document focuses on the impact the Directive is expected to have on the legitimate UK tobacco market, on issues regarding the Directive’s legal base and on the process via which the Directive was developed. We also hope that this document may address some of the concerns raised in the Department of Health’s Explanatory Memorandum on TPD of 4 February 2013. ii. Summary of the TPD’s impact on the UK tobacco market BAT UK believes that the Tobacco Products Directive, if passed in its current form, will have the following consequences for the British tobacco market: The Directive would ban pack formats accounting for 37% of the UK cigarette market and 78% of the UK Handrolling Tobacco (HRT) market. -

A Local Shopping Guide for Families

B8 The Boston Globe FRIDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2020 ComfortZone UNION SQUARE CRAIG F. WALKER/GLOBE STAFF/FILE FRUGAL BOOKSTORE BELMONT BOOKS HENRY BEAR’S PARK ERIN CLARK/GLOBE STAFF/FILE JONATHAN WIGGS/GLOBE STAFF/FILE DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF/FILE By Kara Baskin Lilah Rose GLOBE CORRESPONDENT Locals love this Melrose spot, his year, it’s even more which is a toy store wonderland as in essential to support A local shopping days of old: shelves brimming with small, independent puzzles, classic games (Parcheesi, T businesses. It’s sooth- anyone?), Calico Critters, and more, ingly mechanical to all with curbside pickup and deliv- click over to Amazon and wait for a ery. www.lilahrosemelrose.com brown box to arrive — but that’s not going to help the thousands of guide for families The Merry Lion families around Boston who’ve This Wakefield shop sells funny poured their hopes into a small kids’ clothing (why not buy a “Pies shop, a tiny studio, a life’s passion. Boston is fortunate to have so much creative talent. Before Guys” sweatshirt for your Shop local isn’t a hashtag; it’s a life- tot?), plus toys like dinosaur play- line. It’s on us to support them this season. dough and gifts for grown-ups too. It’s not just about altruism, ei- www.shopthemerrylion.com ther. These places are genuinely amazing. Handmade bibs, 3-D ear- your gently loved books for store fault/files/diversity-catalog.pdf Nantucket Kids rings straight out of Studio 54, credit. www.book-rack.com Mom of three Andrea Romito thoughtfully curated books, on and QUIRKY & FUN owns this preppy hideout at Hing- on. -

JOURNAL DE MONACO� Vendredi 18 Novembre 1994

et a C.) CENT TRENTE-SEPT1EME ANNEP, N° 7.156 Le numéro 7,70 F VENDREDI 18 NOVEMB 1994 SERVICES UMM CENTRALES • JOURNAL DE MONA *1:e Bulletin Officiel de la Principauté JOURNAL HEBDOMADAIRE PARAISSANT LE VENDREDI DIRECTION - REDACTION - ADMINISTRATION MINISTERE D'ETAT - Place de la Visitation - B.P. 622 - MC 98015 MONACO Téléphone : 93.15.80.00 - Compte Chèque Postal 30 1947 T Marseille ABONNEMENT INSERTIONS LÉGALES 1 an (à compter du 1° janvier) la ligne hors taxe : tarifs toutes taxes comprises Greffe Générai - Parquet Général 34,50 F 295,00 F Monaco, France métropolitaine Gérances libres, locations gérances 37,00 F Etranger 360,00 F Commerces (cessions, etc ) 38,00 F Etranger par avion 455,00 F Annexe de la "Propriété Industrielle", seule 145,00 F Société (Statut, convocation aux assemblées, Changement d'adresse 7,00 F avis financiers, etc ...) 40,00 F Microfiches, l'année 450,00 F Avis concernant las associations (constitution, (Remise de 10 % au-delà de la 10' année souscrite) modifications, dissolution) 34,50 F SOMMAIRE Arrêté Ministériel n° 94-494 du 10 noveMbre 1994 autorisant un méde- cin à pratiquer son art en Principauté (p. -1281). ARRÊTÉS MINISTÉRIELS Arrêté Ministériel n° 94-495 du 10 novembre 1994 fixant les modali- tés d'application de l'article 17 de la loi n° 622 du 5 novembre 1956 relative à l'Aviation Civile (p. 1281). A rrêté Ministériel n° 94-487 du 10 novembre 1994 portatufixatim des taux de redevances perçues à l'occution de la mise en fourrière des Arrêté Ministériel n° 94-496 du 10 novembre 1994 fixant les montants véhicules (p. -

09 WBB Guide.Indd

TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION Table of Contents 1 City of Akron, Ohio 2 The Akron Advantage 3 Colleges and Law School 4 Diversity and Student Support 5 Dr. Luis M. Proenza, President 6 2009 Board of Trustees 7 This is Akron Basketball 8-9 This is Rhodes Arena 10-11 UA Athletics Mission Statement / Athlete Involvement 12 Akron Athletics Accomplishments 13 COACHING STAFF Head Coach Jodi Kest 14-15 Associate Head Coach Curtis Loyd 16 Assistant Coaches / Support Staff 16-17 2009-10 SEASON PREVIEW Roster Information 20 TV / Radio Roster 21 Season Outook 22-23 Returner Profiles 24-39 Newcomer Profiles 40-41 MAC Composite Schedule 42 Opponent Information / Lodging Schedule 43 2008-09 SEASON REVIEW Season Statistics 46-49 Career Game-by-Game 50-51 Game Recaps / Box Scores 52-61 AKRON RECORDS & HISTORY All-Time Letterwinners 63 Annual Leaders 64-65 Team Records 66 Single-Game Records 67 Season Records 68 Career Records / All-Americans / Coaching History 69 Team Records 70 Postseason History 71 Year-by-Year Team Statistics 72 All-Time Series Records 73 Year-by-Year Results 74-78 THE UNIVERSITY Quick Facts / Media Policies 80 Tom Wistrcill / Senior Staff 81 ISP Sports Network 82 ISP / Corporate Sponsors 83 Staff Directory 84-85 Mid-American Conference 86-87 Media Outlets 88 CREDITS Writing, Layout and Design: Paul Warner Editorial Assistance: Amanda Aller, Gregg Bach, Mike Cawood Cover Design: David Morris, The Berry Company Photography: John Ashley, Jeff Harwell Printing: Herald Printing (New Washington, Ohio) Follow Akron women’s Basketball on the offi cial web site of UA athletics, www.GoZips.com. -

Make Caldor Your 10Y Store!

20 - EVENING HERALD. Fri.. Nov. 16,197» Experts Say Solar Power Is Efficient HARTFORD (UPI) - Putting the sun to work is an ef The] ubllc has been very receptive to the idea of aolar should expect a return in about five to 10 years. ficient and economically feasible way to tackle the power but needs to learn more of the facts, Ms. Friedland "The real issue is out of pocket expenses. In a very current energy crisis, specialists told a solar power said. short period of time it’s costing you less and less every workshop for the financial community Thursday. "I think the whole issue of ‘heating or eathig' in this month to pay your beat,” Hollander said. Luggage Consultants with a federally funded solar research and part of the country will raise the consciousness about solar,” she said. information group also said the long-term advantages of LooMm to r e AMT The Nr Tari solar power will far outweigh the initial investment as A hot water heating system is the moat practical and learryai the cost of fuel increases. economical solar system an average family can install in DENTIST? ■Mi iM), MMMe, I “Solar power is a pretty simple technology. It’s func an existing home, Hollander said. The type of system Try ut for the poraonal touohl SamnL tional now. It works now. And it la economically depends on the location and construction of &e home, and Our modern office Is conveniently located In East rinl Fw feasible,” said Gayle Friedland, a financial analyst for and W to 120 gallon Unk can cost from $1,000 to $4 000. -

Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1998 Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration Patricia E. Mears Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Mears, Patricia E., "Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration" (1998). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 191. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/191 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and "Exotic" Textile Inspiration by Patricia E. Mears Jessie Franklin Turner was an American couturier who played a prominent role in the emergence of the high-fashion industry in this country, from its genesis in New York during the First World War to the flowering of global influence exerted by Hollywood in the thirties and forties. The objective of this paper is not only to reveal the work of this forgotten designer, but also to research the traditional and ethnographic textiles that were important sources of inspiration in much of her work. Turner's hallmark tea gowns, with their mix of "exotic" fabrics and flowing silhouettes, evolved with the help of a handful of forward-thinking manufacturers and retailers who, as early as 1914, wished to establish a unique American idiom in design. -

Cleveland in a Nutshell

Cleveland in a Nutshell Cleveland Clinic House Staff Spouse Association The House Staff Spouse Association (HSSA) would like to welcome all new Cleveland Clinic residents, fellows and their families to Cleveland. We can help make this move and new phase of your life a little easier. Cleveland in a Nutshell is a resource we hope you will find useful! The information in this booklet is a compilation of information gathered by past and current Cleveland Clinic spouses. It will help you during your relocation to Cleveland and once you’re settled in your new home. After you arrive in Cleveland, the HSSA is a great way to meet new friends and take part in fun events. Our volunteer group is subsidized by the Cleveland Clinic and organizes affordable social functions for residents, fellows, and their families. From discount sporting event tickets to play dates, we are a social and support network. Membership is free and there are no commitments, except to have fun! Look for our monthly meetings and events in our monthly HSSA newsletter – The Stethoscoop-- which will be mailed to your home in Cleveland and addressed to the resident/fellow. In addition to the newsletter, we also have an online community through Yahoo groups! There are over 100 members and we encourage you to join and become an active member in our community. Please email [email protected] for more details. If you have any questions before you arrive, please don’t hesitate to contact one of our officers: President - Erin Zelin (216)371-9303 [email protected] Vice President - Annie Allen (216)320-1780 [email protected] Stethoscoop Editor - Jennifer Lott (216)291-5941 [email protected] Membership Secretary - MiYoung Wang (216)-291-0921 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: The information presented here is a compilation of information from past and current CCF spouses. -

Bonwit Teller's First Female President, 1934-1940 Michael Mamp

Charlotte, North Carolina 2014 Proceedings Hortense Odlum: Bonwit Teller’s first female president, 1934-1940 Michael Mamp, Central Michigan University, USA; Sara Marcketti, Iowa State University, USA Keywords: Hortense Odlum, Bonwit Teller, retail, history From the late 19th century onward, a myriad of new retail stores developed within the United States. These establishments provided shoppers, particularly women, assortments of fashion products that helped shape the American culture of consumption. Authors have explored the role that women played as consumers and entry-level saleswomen in department stores in both America and abroad.1 However, aside from scholarship regarding Dorothy Shaver and her career at Lord & Taylor, little is known about other female leaders of retail companies. Shaver is documented as the first female President of a major American retail company and the “first lady of the merchandising world.”2 However, Hortense Odlum, who served as first President and then Chairwoman of Bonwit Teller from 1934-1944, preceded Shaver by ten years.3 Furthermore, although Bonwit Teller operated for close to a hundred years (1895-1990), the history of the store remains somewhat obscure. Aside from brief summaries in books that speak to the history of department stores, no comprehensive history of the company exists. A historical method approach was utilized for this research. Primary sources included Odlum’s autobiography A Woman’s Place (1939), fashion and news press articles and advertisements from the period, archival records from multiple sources, and oral history.4 The use of multiple sources allowed for the validation of strategies noted in Odlum’s autobiography. Without previous management or business knowledge, Odlum approached her association with the store from the only perspective she really knew, that of a customer first who appreciated quality, style, service, and friendliness.5 She created an environment that catered to a modern woman offering products that would be appreciated, truly a Woman’s Place.