Uptake, Action and Generic Dissent in Anglophone Caribbean Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I COHESION in TRANSLATION

COHESION IN TRANSLATION: A CORPUS STUDY OF HUMAN- TRANSLATED, MACHINE-TRANSLATED, AND NON-TRANSLATED TEXTS (RUSSIAN INTO ENGLISH) A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tatyana Bystrova-McIntyre December, 2012 i © Copyright by Tatyana Bystrova-McIntyre 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Dissertation written by Tatyana Bystrova-McIntyre B.A., Tver State University, Russia, 1999 M.A., Kent State University, OH, 2004 M.A., Kent State University, OH, 2006 Ph.D., Kent State University, OH, 2012 APPROVED BY __________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Brian J. Baer (advisor) __________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Gregory M. Shreve __________________________, Erik B. Angelone __________________________, Andrew S. Barnes __________________________, Mikhail Nesterenko ACCEPTED BY __________________________, Interim Chair, Modern and Classical Language Studies Keiran J. Dunne __________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Timothy Chandler iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................... XIII LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................... XX DEDICATION ......................................................................................................... XXXVI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................... -

Copenhagen Studies in Genre Vol

Roskilde University Genre and Adaptation in motion Svendsen, Erik Published in: Genre and ... Publication date: 2015 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Svendsen, E. (2015). Genre and Adaptation in motion. In S. Auken, P. S. Lauridsen, & A. J. Rasmussen (Eds.), Genre and ... (pp. 221-250). ekbatana. Copenhagen Studies in Genre Vol. 2 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Oct. 2021 GENRE AND … Copenhagen Studies in Genre 2 Ekbátana Ed. Sune Auken, Palle Schantz Lauridsen, & Anders Juhl Rasmussen GENRE AND ... Copenhagen Studies in Genre 2 Edited by Sune Auken, Palle Schantz Lauridsen, & Anders Juhl Rasmussen Forlaget Ekbátana Genre and … Copenhagen Studies in Genre 2 © 2015 Ekbátana and the contributors Edited by Sune Auken, Palle Schantz Lauridsen, & Anders Juhl Rasmussen 1. edition ISBN 978-87-995899-5-1 Typeset in Times New Roman and Helvetica Cover Michael Guldbøg All chapters of this books has been sub- mitted to peer reviewed. -

GENRE STUDIES in MASS MEDIA Art Silverblatt Is Professor of Communications and Journalism at Webster Univer- Sity, St

GENRE STUDIES IN MASS MEDIA Art Silverblatt is Professor of Communications and Journalism at Webster Univer- sity, St. Louis, Missouri. He earned his Ph.D. in 1980 from Michigan State University. He is the author of numerous books and articles, including Media Literacy: Keys to Interpreting Media Messages (1995, 2001), The Dictionary of Media Literacy (1997), Approaches to the Study of Media Literacy (M.E. Sharpe, 1999), and International Communications: A Media Literacy Approach (M.E. Sharpe, 2004). Silverblatt’s work has been translated into Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and German. GENRE STUDIES IN MASS MEDIA A HANDBOOK ART SILVERBLATT M.E.Sharpe Armonk, New York London, England Copyright © 2007 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silverblatt, Art. Genre studies in mass media : a handbook / Art Silverblatt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-7656-1669-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media genres. I. Title. P96.G455S57 2007 302.23—dc22 2006022316 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ BM (c) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my “first generation” of friends, who have been supportive for so long: Rick Rosenfeld, Linda Holtzman, Karen Techner, John Goldstein, Alan Osherow, and Gary Tobin. -

Rhetorical Genre Studies: Key Concepts and Implications for Education

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Academic and Scholarly Repository of KUIS Rhetorical genre studies: Key concepts and implications for education 著者名(英) Dirk MacKenzie journal or 神田外語大学紀要 publication title volume 22 page range 175-198 year 2010-03 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1092/00000620/ asKUIS 著作権ポリシーを参照のこと Rhetorical genre studies: Key concepts and implications for education Dirk MacKenzie Abstract In this paper, I provide an overview of the theoretical roots and key concepts of UKHWRULFDOJHQUHVWXGLHV 5*6 DQGDWWHPSWWRGH¿QHUKHWRULFDOJHQUHWKHRU\,WKHQ discuss implications of rhetorical genre theory for education, with specific focus on: the acquisition process, explicit instruction, discourse community and audience, simulation and authenticity, genre-learning strategies as empowerment, and teacher UROH Introduction In the ‘80s and ‘90s, influenced by a range of theoretical developments related to language use, rhetoric and composition scholars in North America developed a new conceptual framework for genre that has revolutionized writing studies and HGXFDWLRQ5KHWRULFDOJHQUHVWXGLHV 5*6 $UWHPHYD )UHHGPDQ DVLW has come to be called, has given us a new lens, allowing us to see written (and oral) communication in a new way and leading to a deeper understanding of how the form RIRXUFRPPXQLFDWLRQVLVWLHGWRVRFLDOIXQFWLRQV7KHUHVXOWLQJJHQUHWKHRU\KDVKDG major implications for education, since learning to wield genres (especially written JHQUHV LVNH\WRDFDGHPLFVXFFHVV -RKQ6ZDOHV FDOOVJHQUHDQ³DWWUDFWLYH´ZRUGEXWD³IX]]\´FRQFHSW -

Genres of Experience: Three Articles on Literacy Narratives and Academic Research Writing

GENRES OF EXPERIENCE: THREE ARTICLES ON LITERACY NARRATIVES AND ACADEMIC RESEARCH WRITING By Ann M. Lawrence A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Rhetoric and Writing – Doctor Of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT GENRES OF EXPERIENCE: THREE ARTICLES ON LITERACY NARRATIVES AND ACADEMIC RESEARCH WRITING By Ann M. Lawrence This dissertation collects three articles that emerged from my work as a teacher and a researcher. In Chapter One, I share curricular resources that I designed as a teacher of research literacies to encourage qualitative research writers in (English) education to engage creatively and critically with the aesthetics of their research-writing processes and to narrate their experiences in dialogues with others. Specifically, I present three heuristics for writing and revising qualitative research articles in (English) education: “PAGE” (Purpose, Audience, Genre, Engagement), “Problem Posing, Problem Addressing, Problem Posing,” and “The Three INs” (INtroduction, INsertion, INterpretation). In explaining these heuristics, I describe the rhetorical functions and conventional structure of all of the major sections of qualitative research articles, and show how the problem for study brings the rhetorical “jobs” of each section into purposive relationship with those of the other sections. Together, the three curricular resources that I offer in this chapter prompt writers to connect general rhetorical concerns with specific writing moves and to approach qualitative research writing as a strategic art. Chapters Two and Three emerged from research inspired by my teaching, during which writers shared with me personal literacy narratives, or autobiographical accounts related to their experiences with academic research writing. -

Rethinking Mimesis

Rethinking Mimesis Rethinking Mimesis: Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation Edited by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi Rethinking Mimesis: Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation, Edited by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi Layout: Jari Käkelä This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Saija Isomaa, Sari Kivistö, Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Sanna Nyqvist, Merja Polvinen and Riikka Rossi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3901-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3901-3 Table of ConTenTs Introduction: Rethinking Mimesis The Editors...........................................................................................vii I Concepts of Mimesis Aristotelian Mimesis between Theory and Practice Stephen Halliwell....................................................................................3 Rethinking Aristotle’s poiêtikê technê Humberto Brito.....................................................................................25 Paul Ricœur and -

Island Ecologies and Caribbean Literatures1

ISLAND ECOLOGIES AND CARIBBEAN LITERATURES1 ELIZABETH DELOUGHREY Department of English, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 2003 ABSTRACT This paper examines the ways in which European colonialism positioned tropical island landscapes outside the trajectories of modernity and history by segregating nature from culture, and it explores how contemporary Caribbean authors have complicated this opposition. By tracing the ways in which island colonisation transplanted and hybridised both peoples and plants, I demonstrate how mainstream scholarship in disciplines as diverse as biogeography, anthropology, history, and literature have neglected to engage with the deep history of island landscapes. I draw upon the literary works of Caribbean writers such as Édouard Glissant, Wilson Harris, Jamaica Kincaid and Olive Senior to explore the relationship between landscape and power. Key words: Islands, literature, Caribbean, ecology, colonialism, environment THE LANGUAGE OF LANDSCAPE the relationship between colonisation and ecology is rendered most visible in island spaces. Perhaps there is no other region in the world This has much to do with the ways in which that has been more radically altered in terms European colonialism travelled from one island of flora and fauna than the Caribbean islands. group to the next. Tracing this movement across Although Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles the Atlantic from the Canaries and Azores to Darwin had been the first to suggest that islands the Caribbean, we see that these archipelagoes are particularly susceptible to biotic arrivants, became the first spaces of colonial experimen- and David Quammen’s more recent The Song tation in terms of sugar production, deforestation, of the Dodo has popularised island ecology, other the importation of indentured and enslaved scholars have made more significant connec- labour, and the establishment of the plantoc- tions between European colonisation and racy system. -

The Pedagogy of Intertextuality, Genre, and Adaptation: Young Adult Literary Adaptations in the Classroom

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors College 2018 The Pedagogy of Intertextuality, Genre, and Adaptation: Young Adult Literary Adaptations in the Classroom Brooke L. Poeschl Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons The Pedagogvcf. interte lm.tality,and GelU'e, Adaptation� YoWlQ.AdWt. Literacy Adap\atloos intheClas&room (TITLE) BY Brooke L. Poeschl UNDERGRADUATE THESIS SUBMITTED rN PARTrAl FUlFfllMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DEPARTMENT OF .EN.GLISH, ALONG WITH iHE HONORS COLLEGE, €ASr£R-N' .f.LUNOfS UN4VER SffY CHARLESTON, iLLINd1S .'. YEAR 1 HEREBY RECOMMEND.. THJS UNDERGRADUATETHES.JS BE ACCEPTED· AS FULFILLING THE THESIS REQUIREMENT FOR UNDERGRADUATE DEPARTMENTAL HONORS DATE !I?/ 201? HONORS COORDINAfffiR Poeschl 1 The Pedagogy of Intertextuality, Genre, andAdaptation: Young Adult Literary Adaptations in the Classroom Preface There has been a recent shift in the viewpoint of educators in regardto the literary genre known as "Young Adult" (YA L ).1 This genre, with a target audience of readers aged 12 to 18 respectively; is becoming more and more present in the English Language Arts classroom and its application within curriculum has resulted in it sometimes talcingthe place of moretraditionally taught works from the Literary Canon.2 This shift in preference and presence is arguably beneficial to students being that YAL provides a more accessible means by which students can meet Common Core State Standards through texts that are often more interesting to students. Further, there is a growing subset of YAL wherein authors provide a modernized take on literary classics, allowing narratives that have been staples in ELA curricula for decades to become more relatable to their contemporaryadolescent audiences. -

Gender, Ethnicity and Literary Represenation

• 96 • Feminist Africa 7 Fashioning women for a brave new world: gender, ethnicity and literary representation Paula Morgan This essay adds to the ongoing dialogue on the literary representation of Caribbean women. It grapples with a range of issues: how has iconic literary representation of the Caribbean woman altered from the inception of Caribbean women’s writing to the present? Given that literary representation was a tool for inscribing otherness and a counter-discursive device for recuperating the self from the imprisoning gaze, how do the politics of identity, ethnicity and representation play out over time? How does representation shift when one considers the gender and ethnicity of the protagonist in relation to that of the writer? Can we assume that self-representation is necessarily the most “authentic”? And how has the configuration of the representative West Indian writer changed since the 1970s to the present? The problematics of literary representation have been with us since Plato and Aristotle wrestled with the purpose of fiction and the role of the artist in the ideal republic. Its problematics were foregrounded in feminist dialogues on the power of the male gaze to objectify and subordinate women. These problematics were also central to so-called third-world and post-colonial critics concerned with the correlation between imperialism and the projection/ internalisation of the gaze which represented the subaltern as sub-human. Representation has always been a pivotal issue in female-authored Caribbean literature, with its nagging preoccupation with identity formation, which must be read through myriad shifting filters of gender and ethnicity. Under any circumstance, representation remains a vexing theoretical issue. -

Autumn 2003 JSSE Twentieth Anniversary

Journal of the Short Story in English Les Cahiers de la nouvelle 41 | Autumn 2003 JSSE twentieth anniversary Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 ISSN: 1969-6108 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2003 Number of pages: 287-298 ISSN: 0294-04442 Electronic reference Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize, « Olive Senior - b. 1941 », Journal of the Short Story in English [Online], 41 | Autumn 2003, Online since 31 July 2008, connection on 03 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/jsse/337 This text was automatically generated on 3 December 2020. © All rights reserved Olive Senior - b. 1941 1 Olive Senior - b. 1941 Dominique Dubois and Jeanne Devoize EDITOR'S NOTE Interviewed by Dominique Dubois, and Jeanne Devoize., Caribbean Short Story Conference, January 19, 1996.First published in JSSE n°26, 1996. Dominique DUBOIS: Would you regard yourself as a feminist writer? Olive SENIOR: When I started to write, I wasn't conscious about feminism and those issues. I think basically my writing reflects my society and how it functions. Obviously, one of my concerns is gender. I tend to avoid labels. Jeanne DEVOIZE: How can you explain that there are so many women writers in Jamaica, particularly as far as the short story is concerned. O.S.: I think there are a number of reasons. One is that it reflects what happened historically in terms of education: that a lot more women were, at a particular point in time, being educated through high school, through university and so on. -

Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God By

RE-CONNECTING THE SPIRIT: Jamaican Women Poets and Writers' Approaches to Spirituality and God by SARAH ELIZABETH MARY COOPER A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre of West African Studies School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham October 2004 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Chapter One asks whether Christianity and religion have been re-defined in the Jamaican context. The definitions of spirituality and mysticism, particularly as defined by Lartey are given and reasons for using these definitions. Chapter Two examines history and the Caribbean religious experience. It analyses theory and reflects on the Caribbean difference. The role that literary forefathers and foremothers have played in defining the writers about whom my research is concerned is examined in Chapter Three, as are some of their selected works. Chapter Four reflects on the work of Lorna Goodison, asks how she has defined God whether within a Christian or African framework. In contrast Olive Senior appears to view Christianity as oppressive and this is examined in Chapter Five. -

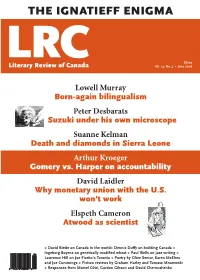

The Ignatieff Enigma

THE IGNATIEFF ENIGMA $6.00 LRCLiterary Review of Canada Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 Lowell Murray Born-again bilingualism Peter Desbarats Suzuki under his own microscope Suanne Kelman Death and diamonds in Sierra Leone Arthur Kroeger Gomery vs. Harper on accountability David Laidler Why monetary union with the U.S. won’t work Elspeth Cameron Atwood as scientist + David Biette on Canada in the world+ Dennis Duffy on building Canada + Ingeborg Boyens on genetically modified wheat + Paul Wells on jazz writing + Lawrence Hill on Joe Fiorito’s Toronto + Poetry by Olive Senior, Karen McElrea and Joe Cummings + Fiction reviews by Graham Harley and Tomasz Mrozewski + Responses from Marcel Côté, Gordon Gibson and David Chernushenko ADDRESS Literary Review of Canada 581 Markham Street, Suite 3A Toronto, Ontario m6g 2l7 e-mail: [email protected] LRCLiterary Review of Canada reviewcanada.ca T: 416 531-1483 Vol. 14, No. 5 • June 2006 F: 416 531-1612 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie 3 Beyond Shame and Outrage 18 Astronomical Talent [email protected] An essay A review of Fabrizio’s Return, by Mark Frutkin ASSISTANT EDITOR Timothy Brennan Graham Harley Alastair Cheng 6 Death and Diamonds 19 A Dystopic Debut CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Anthony Westell A review of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and A review of Zed, by Elizabeth McClung the Destruction of Sierra Leone, by Lansana Gberie Tomasz Mrozewski ASSOCIATE EDITOR Robin Roger Suanne Kelman 20 Scientist, Activist or TV Star? POETRY EDITOR 8 Making Connections A review of David Suzuki: The Autobiography Molly