What Can the Apple Teach the Orange? Lessons U.S. Land Trusts Can Learn from the National Trust in the U.K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beatrix Potter Studies

Patron Registered Charity No. 281198 Patricia Routledge, CBE President Brian Alderson This up-to-date list of the Society’s publications contains an Order Form. Everything listed is also available at Society meetings and events, at lower off-the-table prices, and from its website: www.beatrixpottersociety.org.uk BEATRIX POTTER STUDIES These are the talks given at the Society’s biennial International Study Conferences, held in the UK every other year since 1984, and are the most important of its publications. The papers cover a wide range of subjects connected with Beatrix Potter, presented by experts in their particular field from all over the world, and they contain much original research not readily available elsewhere. The first two Conferences included a wide range of topics, but from 1988 they followed a theme. All are fully illustrated and, from Studies VII onwards, indexed. (The Index to Volumes I-VI is available separately.) Studies I (1984, Ambleside), 1986, reprinted 1992 ISBN 1 869980 00 X ‘Beatrix Potter and the National Trust’, Christopher Hanson-Smith ‘Beatrix Potter the Writer’, Brian Alderson ‘Beatrix Potter the Artist’, Irene Whalley ‘Beatrix Potter Collections in the British Isles’, Anne Stevenson Hobbs ‘Beatrix Potter Collections in America’, Jane Morse ‘Beatrix Potter and her Funguses’, Mary Noble ‘An Introduction to the film The Tales of Beatrix Potter’, Jane Pritchard Studies II (1986, Ambleside), 1987 ISBN 1 869980 01 8 (currently out of print) ‘Lake District Natural History and Beatrix Potter’, John Clegg ‘The Beatrix -

Finding Common Ground

Finding common ground Integrating local and national interests on commons: guidance for assessing the community value of common land Downley Common in the Buckinghamshire Chilterns. About this report This work was commissioned by Natural England and funded through its Ma- jor Project on Common Land. The objective of the work, as given in the work specification, is to identify mechanisms to recognise and take account of local community interests on commons, hence complementing established criteria used in assessing national importance of land for interests such as nature con- servation and landscape. The intention is not that community interests should be graded or weighed and balanced against national interests, but rather that they should be given proper recognition and attention when considering man- agement on a common, seeking to integrate local and national aspirations within management frameworks. Specifically, the purpose of the commission was to provide information to enable the user or practitioner to: i be aware of issues relating to the community interests of common land, ii assess the importance of common land to local neighbourhoods, iii engage with communities and understand their perspectives, iv incorporate community concerns in any scheme examining the future and management of commons. The advice and views presented in this report are entirely those of the Open Spaces Society and its officers. About the authors This report is produced for Natural England by Kate Ashbrook and Nicola Hodgson of the Open Spaces Society. Kate Ashbrook BSc Kate has been general secretary (chief executive) of the Open Spaces Society since 1984. She was a member of the Common Land Forum (1983-6), and the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions’ advisory group on the good practice guide to managing commons (1997-8). -

South East Walker June 2017 a Walk in the Park

SOUTH EAST No. 98 June 2017 Publicwalker path victory at Harrow ocal residents, backed by known as numbers 57 and 58 in the had argued that Harrow Council the Open Spaces Society, London Borough of Harrow, which should make the school reopen the Lthe Ramblers and Harrow have for centuries run in direct lines path, as required by law but instead Hill Trust, have defeated plans by across the land now forming part of the council chickened out and elite Harrow School to move two its grounds. agreed to allow the school to move public footpaths across its sports Footpath 57 follows a north - the path around the obstructions. pitches, all-weather pitches and south route between Football Lane Footpath 58 runs in a direct line Signs point the way from Football Lane. tennis courts. The objectors and Pebworth Road. The school between the bottom of Football fought the plans at a six-day obstructed the footpath with tennis Lane and Watford Road, and objectors represented themselves. straight towards it. The proposed public inquiry earlier this year. courts surrounded by fencing in the school applied to move it to a Appearing as objectors at the diversions are inconvenient and The government inspector, Ms 2003. For nine years, the school zigzag route to avoid the current inquiry were Kate Ashbrook of considerably longer'. Alison Lea, has now rejected the even padlocked the gates across configuration of its sports pitches. the Open Spaces Society and the Says Kate Ashbrook, General proposals. another section of the path but Alison Lea refused the proposals Ramblers, Gareth Thomas MP, Secretary of the Open Spaces Harrow School wanted to move reopened them following pressure principally because of the impact of Harrow councillor Sue Anderson, Society and Footpath Secretary for the two public footpaths, officially from the objectors. -

Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain

Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain Edited by Brendan Prendiville and David Haigron Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain Edited by Brendan Prendiville and David Haigron This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Brendan Prendiville, David Haigron and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4247-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4247-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables and Figures ........................................................................ vii Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Brendan Prendiville Chapter One .............................................................................................. 17 Political Ecology and Environmentalism in Britain: An Overview Brendan Prendiville Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 49 The Transformation of Climate Politics in the UK Neil Carter Chapter Three .......................................................................................... -

Keswick – Crow Park – Derwent Water North Lakes, CA12 5DJ

Keswick – Crow Park – Derwent Water North Lakes, CA12 5DJ Trust New Art: Socially engaged artist residency Artists’ Brief: The view down Derwent Water and Borrowdale from Crow Park Summary of initial ideas and themes: Crow Park was one of the original c1750 of Thomas West’s Lake District “Viewing Stations” and still boasts classic panoramic 360 views across the town towards Skiddaw and Blencathra, and across Derwent water to Catbells, Newlands and the Jaws of Borrowdale. 125 years ago the local vicar in Keswick, Hardwicke Rawnsley, along with his wife and other local people campaigned to secure the Lakes for a much wider constituency of people to enjoy: the vision was that the Lakes were a “national property”, and led to the creation of a “National” Trust, eventually a National Park in the Lakes and finally a “World” Heritage Site. What has been the impact of this vision on the local community, and especially on how they feel about the places on their doorstep, their home turf? And how can we ensure that they remain at the heart of this landscape in terms of feeling a stake in its use, enjoyment, protection, and plans for its future. What we want to achieve: We want to work with artists alongside community consultation to explore what people need from the places we care for NOW and in the future, and how that is different (if it is) from why they came into our care in the first place. In collaboration with our audiences, local partners and arts organisations we will creatively explore alternative visions of the future of this area and test ideas at Crow Park through events and installations working within the leave no physical trace philosophy. -

Local Spaces Open Minds Report

Local Spaces: Open Minds Inspirational ideas for managing lowland commons and other green spaces An Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Published by the Chilterns Conservation Board in March 2015 Local Spaces: Open Minds Inspirational ideas for managing lowland commons and other green spaces o CONSERVATION BOARD HITCHIN The M1 Chilterns Area of DUNSTABLE LUTON Outstanding Natural AYLESBURY Beauty TRING HARPENDEN WENDOVER HEMEL BERKHAMSTED HEMPSTEAD PRINCES RISBOROUGH CHESHAM M25 CHINNOR M40 M1 STOKENCHURCH AMERSHAM CHORLEYWOOD WATLINGTON HIGH BENSON WYCOMBE BEACONSFIELD MARLOW WALLINGFORD M40 N River Thames M25 0 5 10 km HENLEY-ON-THAMES GORING M4 0 6 miles M4 READING Acknowledgements The Chilterns Conservation Board is grateful to the Heritage Lottery Fund for their financial support from 2011 to 2015 which made the Chilterns Commons Project possible. We are also grateful to the project's 18 other financial partners, including the Chiltern Society. Finally, we would like to pay special tribute to Rachel Sanderson who guided the project throughout and to Glyn Kuhn whose contribution in time and design expertise helped to ensure the completion of the publication. Photographs: Front cover main image – Children at Swyncombe Downs by Chris Smith Back cover main image – Sledging on Peppard Common by Clive Ormonde Small images from top to bottom – Children at home in nature by Alistair Will Hazel dormouse courtesy of redorbit.com Orange hawkweed by Clive Ormonde Grazing herd, Brill Common by Roger Stone Discovering trees on a local nature reserve by Alistair Will Local Spaces: Open Minds Determining and setting out a future for key areas of open space, like the 200 commons Preface scattered across the Chilterns, is essential, but a daunting challenge for any individual. -

Why Places Matter to People Research Report

Why places matter to people Research report Visitors at the 2018 Kite Festival at Downhill Demesne and Hezlett House, County Londonderry ©National Trust Images/Chris Lacey Contents I. Foreword 5 II. Executive summary 6 III. Background 10 IV. Results 14 V. Conclusion 32 VI. Appendix 34 2 3 I. Foreward I. Foreword In 1895, the National Trust was founded by Octavia Hill, Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley. They set out with the aim of preserving our nation’s heritage and open spaces for everyone to enjoy forever, based on their belief of the value of these places for fulling a human need in us all. ‘The need of quiet, the need of air, and I believe the sight of sky and of things growing, seem human needs, common to all.’ Octavia Hill, 1888 124 years since it was founded, National Trust memberships are at an all-time high, so it seems that the benefit of places to people is just as important today as it was in 1895. What are the places that make us feel we belong? Why does this relationship exist between people and places? And what are the benefits of having these deep-rooted emotional connections with a place? These are all questions to which we aim to find answers in this report. Visitors at Corfe Castle, Dorset Working with leading researchers at Walnut Unlimited, we have ©National Trust Images/John Millar looked at the importance of people having a deep connection to a ‘special place’, and how that influences the factors that have been proven to influence wellbeing: to connect, be active, take notice, keep learning and to give. -

Natural Environment White Paper

House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee Natural Environment White Paper Written Evidence Only those submissions written specifically for the Committee and accepted by the Committee as evidence for the inquiry Natural Environment White Paper are included. 1 List of written evidence 1 British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) 2 Countryside Alliance 3 Soil Association 3A Soil Association (further submission) 4 The Open Spaces Society 4A The Open Spaces Society (further submission) 5 Landscape Institute 5A Landscape Institute (further submission) 6 British Ecological Society 7 Plantlife 7A Plantlife (further submission) 8 Food Ethics Council 9 Centre for Ecology & Hydrology 10 Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) 10A Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) (further submission) 11 Woodland Trust 11A Woodland Trust (further submission) 12 Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) 12A Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) (further submission) 13 Campaign for National Parks 14 Friends of the Earth England 15 London Wildlife Trust 16 Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT), the Farming & Wildlife Advisory Group (FWAG) and Linking Environment and Farming (LEAF) 17 English Heritage 18 Field Studies Council 19 Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) 19A Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA) (further submission) 20 Local Government Association (LGA) 20A Local Government Association (LGA) (further submission) 21 Food and Drink Federation 22 National Farmers’ Union (NFU) 22A -

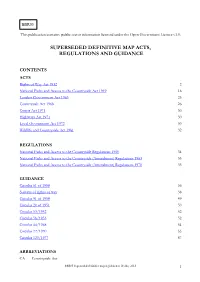

BBR05 Definitive Maps Historical

BBR05 This publication contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. SUPERSEDED DEFINITIVE MAP ACTS, REGULATIONS AND GUIDANCE CONTENTS ACTS Rights of Way Act 1932 2 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 16 London Government Act 1963 25 Countryside Act 1968 26 Courts Act 1971 30 Highways Act 1971 30 Local Government Act 1972 30 Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 32 REGULATIONS National Parks and Access to the Countryside Regulations 1950 34 National Parks and Access to the Countryside (Amendment) Regulations 1963 35 National Parks and Access to the Countryside (Amendment) Regulations 1970 35 GUIDANCE Circular 81 of 1950 36 Surveys of rights of way 38 Circular 91 of 1950 49 Circular 20 of 1951 50 Circular 53/1952 52 Circular 58/1953 52 Circular 44/1968 54 Circular 22/1970 55 Circular 123/1977 57 ABBREVIATIONS CA Countryside Act BBR05 Superseded definitive map legislation at 20 May 2013 1 ACTS This transcript has been made available with the permission of the Open Spaces Society as copyright holder. The text of the Rights of Way Act 1932 is public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. THE COMMONS, OPEN SPACES AND FOOTPATHS PRESERVATION SOCIETY THE RIGHTS OF WAY ACT, 1932 (with special reference to the functions of Local Authorities thereunder) ITS HISTORY AND MEANING By Sir Lawrence Chubb THE TEXT OF THE ACT WITH A COMMENTARY By Humphrey Baker, MA, Barrister-at-Law Reprinted with revisions from the Journal of the Society for October, 1932 First Revision - -

English Women and the Late-Nineteenth Century Open Space Movement

English Women and the Late-Nineteenth Century Open Space Movement Robyn M. Curtis August 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Australian National University Thesis Certification I declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History at the Australian National University, is wholly my own original work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged and has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Robyn M. Curtis Date …………………… ………………… Abstract During the second half of the nineteenth century, England became the most industrialised and urbanised nation on earth. An expanding population and growing manufacturing drove development on any available space. Yet this same period saw the origins of a movement that would lead to the preservation and creation of green open spaces across the country. Beginning in 1865, social reforming groups sought to stop the sale and development of open spaces near metropolitan centres. Over the next thirty years, new national organisations worked to protect and develop a variety of open spaces around the country. In the process, participants challenged traditional land ownership, class obligations and gender roles. There has been very little scholarship examining the work of the open space organisations; nor has there been any previous analysis of the specific membership demographics of these important groups. This thesis documents and examines the four organisations that formed the heart of the open space movement (the Commons Preservation Society, the Kyrle Society, the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association and the National Trust). It demonstrates connections between philanthropy, gender and space that have not been explored previously. -

CIHS April 2015

Industry and the Arts in Cumbria Saturday, 18th April 2015 Who's Who at the Conference John Ruskin [1819-1900] had a love of Lakeland as intense as his loathing of most aspects of modern industry. With Wordsworth he resisted the intrusion of railways, shuddered at the prospect of the “lower orders seeing Helvellyn while drunk” and of Manchester turning Thirlmere into a reservoir. While he found much to criticise in the dehumanising effects and avaricious attitudes accompanying mechanised industry, Ruskin had a profound influence on the emergence in Cumbria of a cluster of manufacturing enterprises where the machine was subordinated to hand labour and nature was taken as the chief inspiration for design. Stephen Wildman is Professor of the History of Art at Lancaster University and Director of its Ruskin Library and Research Centre. He has an impressive list of publications to his name and is widely sought after as a lecturer. His Conference talk will explore Ruskin's role in stimulating the moral and philosophical climate that encouraged and sustained the several communities of painters, carvers, furniture makers, metal and textile workers that were distinctive in the Cumbria of the mid- nineteenth century and were precursors to the main flowering of the Arts and Crafts Movement. The Keswick School of Industrial Arts began in 1884 as an evening class in repousé metalwork arranged by Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley and his wife Edith at the Crosthwaite Parish Rooms. Rawnsley had felt the influence of Ruskin while at Oxford and set about giving practical effect to his teachings “to counteract the pernicious effect of turning men into machines . -

Great Heritage 2020 Castles, Historic Houses, Gardens & Cultural Attractions

FAMILY DAYS OUT • ALL WEATHER ATTRACTIONS • WHAT’S ON LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 2020 CASTLES, HISTORIC HOUSES, GARDENS & CULTURAL ATTRACTIONS www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Welcome to Cumbria’s Living Heritage Cumbria’s Living Heritage brings you an exclusive collection of over 30 unique attractions and cultural destinations in and around the Lake District. This year we are celebrating three significant anniversaries - William Wordsworth’s 250th anniversary, the 125th anniversary of the National Trust and the centenary of the death of its founder, Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley. Join us to celebrate their lives and achievements and enjoy the landscapes they loved and protected. We have a full programme of events throughout the year, here is just a selection. FEBRUARY /MARCH DECEMBER 28 Feb - 1 Mar Askham Hall: Classical Music Festival 26 Lakeland Motor Museum: Classic Drive & Ride 14 & 15 Dalemain: Marmalade Awards & Festival REGULAR GARDEN TOURS 27 Birdoswald Roman Fort, Walking the Roman Mile Brantwood 2.15pm Wed, Fri & Sun Apr-Oct APRIL / EASTER Holehird Gardens 11am Wednesday May-Sept 4 Lakeland Motor Museum: Drive It Day Levens Hall Gardens 2pm Tuesday Apr-Oct 10-13 Steam Yacht Gondola: Evening Cruises SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS 18 Celebrate World Heritage Day at Allan Bank Until - 19 Apr Blackwell: The Arts & Crafts of Politics with Wordsworth Grasmere and Keswick Museum 1 Feb - Dec Keswick Museum: The Stories of Keswick MAY 15 Feb - 1 Nov Beatrix Potter Gallery: ‘Friendship 2 & 3 Holker Hall: Spring Fair by Post’ 2 & 3 Swarthmoor Hall: Printfest Collection Exhibit 17 Feb - Nov Swarthmoor Hall: The Quaker Story 8 - 10 Muncaster: Victorious Food Fest 14 Mar - 8 Nov Wordsworth House and Garden: 10 Hutton-in-the-Forest: Plant and Food Fair The Child is Father of the Man 17 Holehird Gardens: Open Day/Meet the Gardeners 21 Mar – 1 Nov Sizergh Castle: One Place, One Family, 800 Years 24 Hutton-in-the-Forest: Classic Cars in the Park 20 Mar - Dec Brantwood: The Treasury.