Deforestation Drivers and Human Rights in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4-The-Truth-About-Sarawaks-Forest

8/28/2020 The Truth About Sarawak's 'Forest Cover' - Why Shell Should Think Twice Before Engaging With The Timber Crooks | Sarawak Report Secure Key Contact instructions Donate to Sarawak Report Facebook Twitter Sarawak Report Latest Stories Sections Birds Of A Feather Flock Together? "I Am Alright Jack" AKA Najib Razak? Coup Coalition's 1MDB Cover-Up Continues As Talks Confirmed With IPIC GOLF DIPLOMACY AND "BACK-CHANNEL LOBBYING" - US$8 Million To Lobby President Trump, But Najib's Golf Got Cancelled! The Hawaii Connection - How Jho Low Secretly Lobbied Trump For Najib Over 1MDB! 'Back To Normal' With The Same Tired Tricksters And Their Same Old Playbook - Of Sex, Lies and Videotape Stories Talkbacks Campaign Platform Speaker's Corner Press About Sarawak Report Tweet https://www.sarawakreport.org/2019/06/the-truth-about-sarawaks-forest-cover-why-shell-should-think-before-engaging-with-the-timber-crooks/ 1/5 8/28/2020 The Truth About Sarawak's 'Forest Cover' - Why Shell Should Think Twice Before Engaging With The Timber Crooks | Sarawak Report The Truth About Sarawak's 'Forest Cover' - Why Shell Should Think Twice Before Engaging With The Timber Crooks 16 June 2019 Looking for all the world like a gruesome bunch of mafia dons, the head honchos of Sarawak dressed casual this weekend and waddled out to some turf to grin for their favourite PR organ, the Borneo Post (owned by the timber barons of KTS) in order to proclaim their belated attempt to get onto the tree planting band-waggon. The broad face of the mysteriously wealthy deputy chief minister, Awang Tengah dominated the shot (his earlier positions included chairman and director of the Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation and minister of Urban Development and Natural Resources). -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

20 Julai 2020, Pukul 10.00 Pagi

MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT ATURAN URUSAN MESYUARAT NASKAH SAHIH/BAHASA MALAYSIA http://www.parlimen.gov.my HARI ISNIN, 20 JULAI 2020, PUKUL 10.00 PAGI Bil. 6 PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN BAGI JAWAB LISAN 1. PR-1432-L09737 Dr. Nik Muhammad Zawawi bin Haji Salleh [ Pasir Puteh ] minta MENTERI PEMBANGUNAN USAHAWAN DAN KOPERASI menyatakan adakah pihak Kementerian mempunyai perancangan untuk memperkenalkan program Pengekalan PKS dalam memastikan PKS dapat melindungi pendapatan dan mampu bertahan sebagai antara pemain utama ekonomi pasca COVID-19. 2. PR-1432-L10003 Dato' Seri Anwar bin Ibrahim [ Port Dickson ] minta MENTERI SUMBER MANUSIA menyatakan unjuran kadar pengangguran negara dan anggaran jumlah penduduk yang menganggur sehingga akhir tahun ini serta menyatakan langkah-langkah yang diambil Kementerian dalam mengatasi lonjakan kenaikan kadar pengangguran terkini. 3. PR-1432-L08972 Tuan Ahmad Johnie bin Zawawi [ Igan ] minta MENTERI PEMBANGUNAN LUAR BANDAR menyatakan apakah perancangan jangka pendek dan jangka panjang pihak FELCRA BHD di kawasan Parlimen P.207 Igan untuk membantu meningkatkan pendapatan para peserta kelapa sawit. Berapakah keluasan keseluruhan tanaman kelapa sawit yang diselenggarakan oleh pihak FELCRA BHD di Kawasan Parlimen P.207 Igan dan jumlah peserta yang terlibat. 4. PR-1432-L08846 Tuan Fong Kui Lun [ Bukit Bintang ] minta MENTERI DALAM NEGERI menyatakan indeks jenayah di Kuala Lumpur sebelum, semasa dan selepas tamat tempoh Perintah Kawalan Pergerakan (PKP). 2 AUM DR 20/7/2020 5. PR-1432-L09141 Dato' Haji Ahmad Nazlan bin Idris [ Jerantut ] minta MENTERI PEMBANGUNAN USAHAWAN DAN KOPERASI menyatakan mekanisme serta inisiatif yang diambil oleh Kementerian bagi membantu perkembangan koperasi di Malaysia terutama koperasi yang baru ditubuhkan atau yang bergelut dengan masalah aliran tunai. -

A Taxonomic Revision of the Myrmecophilous Species of the Rattan Genus Korthalsia (Arecaceae)

A taxonomic revision of the myrmecophilous species of the rattan genus Korthalsia (Arecaceae) Article Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Shahimi, S., Conejero, M., Prychid, C. J., Rudall, P. J., Hawkins, J. and Baker, W. J. (2019) A taxonomic revision of the myrmecophilous species of the rattan genus Korthalsia (Arecaceae). Kew Bulletin, 74 (4). 69. ISSN 0075-5974 doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-019-9854-x Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/88338/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12225-019-9854-x Publisher: Springer All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online KEW BULLETIN (2019) 74: 69 ISSN: 0075-5974 (print) DOI 10.1007/S12225-019-9854-X ISSN: 1874-933X (electronic) A taxonomic revision of the myrmecophilous species of the rattan genus Korthalsia (Arecaceae) Salwa Shahimi1,2,3, Maria Conejero2, Christina J. Prychid2, Paula J. Rudall2, Julie A. Hawkins1 & William J. Baker2 Summary. The rattan genus Korthalsia Blume (Arecaceae: Calamoideae: Calameae) is widespread in the Malesian region. Among the 28 accepted species are 10 species that form intimate associations with ants. -

The Taib Timber Mafia

The Taib Timber Mafia Facts and Figures on Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs) from Sarawak, Malaysia 20 September 2012 Bruno Manser Fund - The Taib Timber Mafia Contents Sarawak, an environmental crime hotspot ................................................................................. 4 1. The “Stop Timber Corruption” Campaign ............................................................................... 5 2. The aim of this report .............................................................................................................. 5 3. Sources used for this report .................................................................................................... 6 4. Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 6 5. What is a “PEP”? ....................................................................................................................... 7 6. Specific due diligence requirements for financial service providers when dealing with PEPs ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 7. The Taib Family ....................................................................................................................... 9 8. Taib’s modus operandi ............................................................................................................ 9 9. Portraits of individual Taib family members ........................................................................ -

The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds

Seattle Pacific University Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring 6-7-2021 The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds Chea-Mun Tan Seattle Pacific University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Economics Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Tan, Chea-Mun, "The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia's 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds" (2021). Honors Projects. 131. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/131 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. The 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) Scandal: Exploring Malaysia’s 2018 General Elections and the Case for Sovereign Wealth Funds by Chea-Mun Tan First Reader, Dr. Doug Downing Second Reader, Dr. Hau Nguyen A project submitted in partial fulfillMent of the requireMents of the University Scholars Honors Project Seattle Pacific University 2021 Tan 2 Abstract In 2015, the former PriMe Minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, was accused of corruption, eMbezzleMent, and fraud of over $700 million USD. Low Taek Jho, the former financier of Malaysia, was also accused and dubbed the ‘mastermind’ of the 1MDB scandal. As one of the world’s largest financial scandals, this paper seeks to explore the political and economic iMplications of 1MDB through historical context and a critical assessMent of governance. Specifically, it will exaMine the economic and political agendas of former PriMe Ministers Najib Razak and Mahathir MohaMad. -

South Africa: January 2020 Newsletter

Newsletter January 2020 Plantations in the Kokstad area of KwaZulu-Natal Photo: Jenny Duvenage [email protected] │ +27 (0) 82 652 1533 │ www.timberwatch.org.za c/o groundWork at the Phansi Museum, 500 Esther Roberts Rd, Glenwood PO Box 59072 Umbilo 4075 Durban South Africa Will 2020 be the year shift happens? IN THIS ISSUE The past year has been incredibly eventful. Major 1-2 Will 2020 be the year shift happens? public dissent is taking place and a battle on a global 2-6 Africa scale is showing signs of developing. Essentially, this is Africa is the focus of the New Bioeconomy between ordinary people and powerful corporate Traditional Khoisan Leadership Bill: President signs away rural forces although it may be framed differently by various people’s rights factions, ideologies and aspiring ‘leaders’ attempting to New frontier of the palm oil industry dominate and own the new story that is beginning to Ecofeminists fight for Uganda's forests unfold. A disaster for water resources in Mpumalanga The trouble with mass tree planting At its core, this battle is the unending struggle for ‘I will not dance to your beat’ a poem by Nnimmo Bassey justice; self-determination; and a fair, equitable system 6-11 Climate Resistance and COP25 for the majority of the Earth’s citizens but this time the Neoliberalism began in Chile and will die in Chile stakes have never been higher. The final three months In Defence of Life: The resistance of indigenous women of 2019 ended with waves of civil unrest erupting COP25 and Cumbre de los Pueblos (The People’s Summit) around the world in protests against corrupt, self- The Coming Green Colonialism by Nnimmo Bassey serving governments pursuing anti-people, anti- 11-14 Stand with the Defenders of Life democratic and anti-environmental policies on behalf Death of courageous Indonesian eco-activist Golfrid Siregar of a neo-feudal, corporate elite. -

Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Asia and Africa Volume II Table of Contents

Final Report Submitted to the United States Agency for International Development Conflict Timber: Dimensions of the Problem in Asia and Africa Volume II Asian Cases Authors James Jarvie, Forester Ramzy Kanaan, Natural Resources Management Specialist Michael Malley, Institutional Specialist Trifin Roule, Forensic Economist Jamie Thomson, Institutional Specialist Under the Biodiversity and Sustainable Forestry (BIOFOR) IQC Contract No. LAG-I-00-99-00013-00, Task Order 09 Submitted to: USAID/OTI and USAID/ANE/TS Submitted by: ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, Vermont USA 05401 Tel: (802) 658-3890 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS............................................................................................................................................................ ii OVERVIEW OF CONFLICT TIMBER IN ASIA ................................................................................................1 INDONESIA CASE STUDY AND ANNEXES......................................................................................................6 BURMA CASE STUDY.......................................................................................................................................106 CAMBODIA CASE STUDY ...............................................................................................................................115 LAOS CASE STUDY ...........................................................................................................................................126 NEPAL/INDIA -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

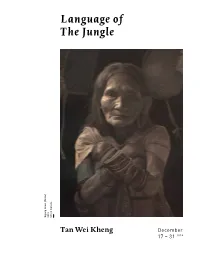

Language of the Jungle

Language of The Jungle Oil on Canvas Sigang Kesei (Detail) Sigang Kesei 2013 Tan Wei Kheng December 17 – 31 2014 Has the jungle become more beautiful? The artist Tan Wei Kheng paints portraits of the unseen heroes of the nomadic Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia. He invites us to discover the values and dreams of the Penans, who continue with their struggles in order to live close to nature. Tan is also involved in other initiatives and often brings with him rudimentary Language Of supplies for the Penans such as rice, sugar, tee shirts, and toothpaste. As natural – Ong Jo-Lene resources are destroyed, they now require supplements from the modern world. The Jungle Kuala Lumpur, 2014 Hunts do not bear bearded wild pigs, barking deers and macaques as often anymore. Now hunting takes a longer time and yields smaller animals. They fear that the depletion of the tajem tree from which they derive poison for their darts. The antidote too is from one specific type of creeper. The particular palm tree that provides leaves for their roofs can no longer be found. Now they resort to buying tarpaulin for roofing, which they have to carry with them every time they move Painting the indigenous peoples of Sarawak is but one aspect of the relationship from camp to camp. Wild sago too is getting scarcer. The Penans have to resort to that self-taught artist, Tan Wei Kheng has forged with the tribal communities. It is a farming or buying, both of which need money that they do not have. -

Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key?

sustainability Article Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key? Nadzirah Hosen 1,* , Hitoshi Nakamura 2 and Amran Hamzah 3 1 Graduate School of Engineering and Science, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan 2 Department of Planning, Architecture and Environmental Systems, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Built Environment and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai 81310, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 December 2019; Accepted: 15 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: The traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often neglected despite its significance in combating climate change. This study uncovers the potential of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) from the perspective of indigenous communities in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, and explores how TEK helps them to observe and respond to local climate change. Data were collected through interviews and field work observations and analysed using thematic analysis based on the TEK framework. The results indicated that these communities have observed a significant increase in temperature, with uncertain weather and seasons. Consequently, drought and wildfires have had a substantial impact on their livelihoods. However, they have responded to this by managing their customary land and resources to ensure food and resource security, which provides a respectable example of the sustainable management of terrestrial and inland ecosystems. The social networks and institutions of indigenous communities enable collective action which strengthens the reciprocal relationships that they rely on when calamity strikes. -

A Revision of Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. (Vitaceae) in Sarawak, Borneo

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317746026 A revision of Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. (Vitaceae) in Sarawak, Borneo Article in Malayan Nature Journal · January 2017 CITATION READS 1 324 4 authors, including: Wan Nuur Fatiha Wan Zakaria Aida Shafreena Ahmad Puad University Malaysia Sarawak University Malaysia Sarawak 5 PUBLICATIONS 10 CITATIONS 9 PUBLICATIONS 30 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ramlah bt Zainudin University Malaysia Sarawak 59 PUBLICATIONS 205 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Characterizations of peptides from Borneon frogs skin secretion View project Molecular Phlogeny of Genus Hylarana View project All content following this page was uploaded by Wan Nuur Fatiha Wan Zakaria on 02 May 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Malayan Nature Journal 2017, 69(1), 71 - 90 (Updated 31-5-2017) A revision of Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. (Vitaceae) in Sarawak, Borneo WAN NUUR FATIHA WAN ZAKARIA1, AIDA SHAFREENA AHMAD PUAD1, *, RAMLAH ZAINUDIN2 and A. LATIFF3 Abstract: A revision of the genus Tetrastigma (Miq.) Planch. in Sarawak is presented. A total of 11 Tetrastigma species in Sarawak are recorded namely T. brunneum Merrill, T. dichotomum (Blume) Planch., T. diepenhorstii (Miq.) Latiff, T. dubium (Laws.) Planch., T. glabratum (Blume) Planch., T. hookeri (Lawson) Planch., T. megacarpum Latiff, T. papillosum (Blume) Planch., T. pedunculare (Wall. ex Laws.) Planch., T. rafflesiae (Miq.) Planch., and T. tetragynum Planch. Morphological descriptions are given for each taxon, as well as a key for identification. A general discussion on the growth habits and morphology of stem, inflorescence, flowers, fruits and seeds is also given.