Family-Centered Community Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbus Near East Side BLUEPRINT for COMMUNITY INVESTMENT Acknowledgements the PARTNERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE the PACT TEAM President E

Columbus Near East Side BLUEPRINT FOR COMMUNITY INVESTMENT Acknowledgements THE PARTNERS ADVISORY COMMITTEE THE PACT TEAM President E. Gordon Gee, The Ohio State University Tim Anderson, Resident, In My Backyard Health and Wellness Program Trudy Bartley, Interim Executive Director Mayor Michael B. Coleman, City of Columbus Lela Boykin, Woodland Park Civic Association Autumn Williams, Program Director Charles Hillman, President & CEO, Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority Bryan Brown, Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority (CMHA) Penney Letrud, Administration & Communications Assistant (CMHA) Willis Brown, Bronzeville Neighborhood Association Dr. Steven Gabbe, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Reverend Cynthia Burse, Bethany Presbyterian Church THE PLANNING TEAM Goody Clancy Barbara Cunningham, Poindexter Village Resident Council OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE ACP Visioning + Planning Al Edmondson, Business Owner, Mt. Vernon Avenue District Improvement Fred Ransier, Chair, PACT Association Community Research Partners Trudy Bartley, Interim Executive Director, PACT Jerry Friedman, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Skilken Solutions Jerry Friedman, Associate Vice President, Health Services, Ohio State Wexner Columbus Policy Works Medical Center Shannon Hardin, City of Columbus Radio One Tony Brown Consulting Elizabeth Seely, Executive Director, University Hospital East Eddie Harrell, Columbus Urban League Troy Enterprises Boyce Safford, Former Director of Development, City of Columbus Stephanie Hightower, Neighborhood -

Ohio's 3Rd District (Joyce Beatty - D) Through 2018 LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3Rd District Through 2018

LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3rd District (Joyce Beatty - D) Through 2018 LIHTC Properties in Ohio's 3rd District Through 2018 Annual Low Rent or HUD Multi-Family Nonprofit Allocation Total Tax-Exempt Project Name Address City State Zip Code Allocated Year PIS Construction Type Income Income Credit % Financing/ Sponsor Year Units Bond Amount Units Ceiling Rental Assistance Both 30% 1951 PARSONS REBUILDING LIVES I COLUMBUS OH 43207 Yes 2000 $130,415 2000 Acquisition and Rehab 25 25 60% AMGI and 70% No AVE present value 3401 QUINLAN CANAL Not STRATFORD EAST APTS OH 43110 Yes 1998 $172,562 2000 New Construction 82 41 BLVD WINCHESTER Indicated 4855 PINTAIL CANAL 30 % present MEADOWS OH 43110 Yes 2001 $285,321 2000 New Construction 95 95 60% AMGI Yes CREEK DR WINCHESTER value WHITEHALL SENIOR 851 COUNTRY 70 % present WHITEHALL OH 43213 Yes 2000 $157,144 2000 New Construction 41 28 60% AMGI No HOUSING CLUB RD value 6225 TIGER 30 % present GOLF POINTE APTS GALLOWAY OH 43119 No 2002 $591,341 2001 Acquisition and Rehab 228 228 Yes WOODS WAY value GREATER LINDEN 533 E STARR 70 % present COLUMBUS OH 43201 Yes 2001 $448,791 2001 New Construction 39 39 50% AMGI No HOMES AVE value 423 HILLTOP SENIOR 70 % present OVERSTREET COLUMBUS OH 43228 Yes 2001 $404,834 2001 New Construction 100 80 60% AMGI No VILLAGE value WAY Both 30% 684 BRIXHAM KINGSFORD HOMES COLUMBUS OH 43204 Yes 2002 $292,856 2001 New Construction 33 33 60% AMGI and 70% RD present value 30 % present REGENCY ARMS APTS 2870 PARLIN DR GROVE CITY OH 43123 No 2002 $227,691 2001 Acquisition and -

March 14 Safer Together Day Staff

Tracey D. Johnson, President The CEA Voice Volume XLVII, No. 28 Columbus Education Association March 12, 2018 functions and policy-making powers of the State Board of March 14 Safer Together Day Education (SBOE) to the new department. Under the bill, SBOE During the March 6 CCS Board of Education meeting, would oversee teacher licensure and educator misconduct. OEA is the board adopted a resolution in support of our students and opposed to this bill. staff in response to the gun violence in our communities and On Tuesday, February 27, 2018, supporters of the bill offered our nation. District Administration met with a focus group of proponent testimony in a hearing before the House Government students to get their thoughts on how we should respond to Accountability and Oversight Committee. Te proposal was the call for a nationwide student walk-out on Wednesday, praised by officials from Governor Kasich’s administration. John March 14. Te District calls the day Safer Together Day. Carey, Chancellor of the Ohio Department of Higher Education What is the National School Walkout? Students, school and Ryan Burgess, Director of the Governor’s Office of Workforce faculty and supporters around the world will walk out of their Transformation stated that the bill will lead to greater schools to honor those killed in the massacre at the Parkland coordination and collaboration. Among others providing High School in Florida earlier this year for 17 minutes at 10 testimony in favor of HB 512 were Dennis Franks, a.m. on Wednesday, March 14. Tose participating are Superintendent of the Pickaway-Ross Career and Technology encouraged to wear orange – the color used by many who Center; Ron Larussi, Superintendent of the Mahoning County support gun control. -

Short North Parking Plan Details

FINAL PLAN DETAIL SHEET TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary Zones Rates & Restrictions Benefit District Enforcement Employees Residents Guest Privileges Visitors Assessment & Evaluation Miscellaneous Plan Provisions PLAN SUMMARY BENEFIT DISTRICT All revenue, after administrative and operating costs, will be shared with the district. HOURS Meters: 8a - 10p Permit Zones: Three-hour limit 8a - 10p | Permit only 10p - 8a RATES Meters: $1/hr from 8a - 3p | $2/hr from 3p - 10p Permit Zones: SNC & SND - $1/hr from 8a -3p & $2/hr from 3p - 10p SNA, SNB, & SNE - $2/hr from 8a - 3p & $3/hr from 3p - 10p PERMITS Residential: 1/licensed driver with a maximum of 2/address Employee: 10/business with time restrictions after 4 permits PERMIT FEES Residential: $25/permit & an additional $25/address for guest privileges Employee: $100/permit for the first 4 permits and $200-$700 for permits 5 through 10 GUEST PARKING See plan details for more information. MOBILITY OPTIONS Car Share: Revising rules & regulations to expand program. Remote Parking: For employees downtown with parking operator. Evening Service: Exploring shuttle options. ASSESSMENT Initial 6 month stabilization period, then quarterly evaluation and modification. Will Assess: rates, permit utilization, and mobility options. Rates will increase a quarter ($0.25) per quarter (3 months) if needed. ZONES GOAL Create consistent parking zones that are easily understandable to the parking public and can be efficiently enforced. Parking zones are utilized to better manage parking demand in a defined geographic area. Zones were drawn to incorporate varying parking demand, with high parking demand closer to High Street and lower parking demand away from High Street. -

University District Plan

University District Plan Columbus Planning Division University District Plan Columbus Planning Division 50 w. Gay street, fourth floor Columbus, ohio 43215 CITY COUNCIL UNIVERSITY AREA COMMISSION Andrew J. Ginther, Council President Doreen Uhas-Sauer President Hearcel F. Craig Susan Keeny 1st Vice President Shannon G. Hardin David Hegley 2nd Vice President Zachary M. Klein Sharon Young Corresponding Secretary Michelle M. Mills Terra Goodnight Recording Secretary Eileen Y. Paley Seth Golding Treasurer Priscilla R. Tyson James Bach Racheal Beeman (elect) DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION Craig Bouska Michael J. Fitzpatrick, Chair Ethan Hansen John A. Ingwersen, Vice Chair Joyce Hughes Marty Anderson Rory Krupp (elect) Maria Manta Conroy Jennifer Mankin John A. Cooley Brandyn McElroy Kay Onwukwe Colin Odden Stefanie Coe Charles Robol Michael Sharvin (elect) Deb Supelak DEPARTMENT OF DEVELOPMENT Richard Talbott Steve Schoeny Director Stephen Volkmann Vince Papsidero, FAICP Deputy Director Tom Wildman PLANNING DIVISION UNIVERSITY AREA REVIEW BOARD Kevin Wheeler Planning Administrator Fredric (Ted) Goodman, aia Chair Mark Dravillas, aiCP Assistant Administrator Pasquale Grado, aia Dan Ferdelman, aia Urban Designer Brian Horne, aia Marc Cerana, GIS Analyst George Kane, aia Todd Singer, aiCP, J.D. Senior Planner Robert Mickley Christine Leed Senior Planner Frank Petruziello, aia Victoria Darah Planning Volunteer Doreen Uhas Sauer Contents Section 1 6 Section 3 38 Section 4 78 Introduction Recommendations Implementation Planning Area 9 Land Use Plan 40 Plan -

Osu Research Project Mapping the Food Environment Seeks Better Understanding of Columbus Residents’ Food Access

The Food Innovation Center 215 Parker Building 064 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 2015 Fyffe Road Columbus, OH 43210-1007 WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2014 614-292-0229 Phone 614-292-0218 Fax Press Contact: [email protected] fic.osu.edu Ben Kerrick, Project Coordinator [email protected] foodmapping.osu.edu OSU RESEARCH PROJECT MAPPING THE FOOD ENVIRONMENT SEEKS BETTER UNDERSTANDING OF COLUMBUS RESIDENTS’ FOOD ACCESS COLUMBUS, Ohio – An ambitious OSU research project hopes to gain a better understanding of how and where residents of central Columbus get their food, and what factors influence their decisions about what they eat. The project, entitled “Mapping the Food Environment,” is funded by OSU’s Food Innovation Center, and is led by the Food Mapping Team, an interdisciplinary team of researchers and community partners. As part of the research effort, the team is administering a survey to residents of certain ZIP Codes in central Columbus, covering the neighborhoods of Milo-Grogan, Weinland Park, Victorian Village, Italian Village, Downtown, Franklinton and the Near East Side during the first phase of data collection. The survey is offered in-person during select hours at several public locations in the study area, and can also be taken online at: go.osu.edu/FoodSurvey. The survey, which takes about 20 minutes to complete, includes questions about where people get their food, what kinds of foods they buy, and whether they experience food insecurity. Survey participants are eligible to enter a raffle for prizes including grocery giftcards and Apple iPad Minis. The results will be used to conduct a detailed spatial analysis of the “food environment” of Columbus, and to understand how the food environment varies across these neighborhoods. -

Message from Mayor Andrew J. Ginther

Message from Mayor Andrew J. Ginther As we begin 2016, I am excited about the future of our city and all the new programs and facilities the Columbus Recreation and Parks Department will be featuring. Currently, their 230+ parks, 29 recreation centers, 7 outdoor pools, athletic complexes, golf courses and a trail system that provide opportunities for all of our residents to lead a healthy life. In the coming months, the department will offer even more possibilities for Central Ohioans to improve their quality of life while making a positive economic impact on the city. This spring, the department is anticipating the reopening of Douglas, Glenwood and Driving Park Recreation Centers that were closed for renovations. In the summer, Driving Park will unveil a new 8,500 square foot swimming pool and will continue to add to the Central Ohio Greenways Columbus City Council trail for Columbus biking enthusiasts. Later in the year, the department Zachary M. Klein, President anticipates their new Greg S. Lashutka Event Center to open giving Elizabeth C. Brown residents more rental space for meetings, weddings and other events. Mitchell J. Brown Shannon G. Hardin We know our programs mean so much more to a community than Jaiza N. Page just places to play and enjoy the outdoors. Our programs truly have Michael Stinziano a positive impact on our residents’ quality of life. In fact our centers Priscilla R. Tyson are a starting point for many young people to learn life skills and to participate in team and individual activities. We promote active, healthy Columbus Recreation & Parks Department Commission living and our centers are a safe environment after school, in the evening, on weekends and throughout the summer. -

City of Columbus Secures Court Order to Shut Down Short North Carryout

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Friday, July 13, 2018 Contact: Meredith Tucker, 614.965.0203 Email: [email protected] City of Columbus Secures Court Order to Shut Down Short North Carryout ‘High Five Spice Emporium’ to immediately stop selling alcohol, must cease all operations today after judge issues order COLUMBUS, OH— Columbus City Attorney Zach Klein announced today that the City of Columbus secured a court order to vacate and shutter the High Five Spice Emporium, a carryout store that has plagued the Short North with violence and crime for years. It is the seventh business City Attorney Klein has closed down due to unlawful and irresponsible business practices since he took office in January. The property will be boarded up today at 12:00 p.m. The Franklin County Environmental Court issued the order after the City Attorney’s office filed a complaint for preliminary and permanent injunctive relief against the establishment that, according to officer testimony, accounted for as many as one-third of all police runs in a precinct that encompasses several neighborhoods, including Weinland Park, the University District, Harrison West, Italian Village, Victorian Village and Fifth-by-Northwest. The order, stating that the City of Columbus “has established by clear and convincing evidence that the [High Five Spice Emporium] presents a threat of irreparable harm to the community due to the history of alcohol violations and acts of violence,” requires the carryout to immediately stop selling alcohol and declares that the premises shall be boarded up today, Friday, July 13, 2018 at 12:00 p.m. “This is now the seventh business we have shut down since January for operating unlawfully and irresponsibly and hopefully it sends a message to others to clean up their act,” said Columbus City Attorney Zach Klein. -

Community Reinvestment Areas

Godown Morse Community Reinvestment Areas n Davidso Henderson HOUSING DIVISION Ferris Cooke Easton Way Cooke M C o he r r Cooke s ry e B Maize C o ro t Karl t ss o in m Reed g Mccoy CRA STATUS Riverside Innis Market Ready Westerville Cemetery O l e Indianola n Mccutcheon Dublin t Oakland Park Ready for Revitalization a North Broadway Fishinger n g Stygler n ow y st n R h i o v Agler 270 J Ready for Opportunity e r Weber Mcguey Cleveland Tremont High Agler Ackerman Mill Granville CRA INFORMATION Dodridge 62 The designations approved by City Council are listed below. Hudson Northwest Mock Stelzer Sunbury . AC Humko Berrell Johnstown 33 Lane 71 . Fifth By Northwest Cassady . Franklinton Joyce Roberts 315 . Hilltop 17th Holt International G . Linden Fourth at eway Kinnear . Livingston and James Kenny Summit t 11th r o . Milo-Grogan p ir A King . Near East Trabue Brentnell 5th . North Central . Short North 3rd 5th Dublin Neil Starr . Southside 2nd Nelson . Weinland Park Wilson Leonard Grandview 670 St Clair Goodale Goodale Mt Vernon s 16 r e v i Taylor Fisher R Hamilton n Nationwide Naughten Twi Broad Spring Long M Grant a r Governor Valleyview McKinley c Phillipi o n i Third Souder Bryden Hartford 40 Town Rich Yearling Central Main Front James Town Rich Davis Glenwood 0 0.5 1 2 Miles 70 Cole Hague Ohio Coordinate System: State Plane Ohio South; U.S. Foot; North American Datum Miller Sullivant Kelton Livingston College Date: .. Mound Whittier Edited: .. Greenlawn Thurman Created by: Lockbourne Eakin Fairwood Columbus Planning Division/mc Stimmel W. -

COLUMBUS CITY COUNCIL MEETING HIGHLIGHTS for Immediate Release: February 22, 2016

COLUMBUS CITY COUNCIL MEETING HIGHLIGHTS For Immediate Release: February 22, 2016 For More Information: Lee Cole, (614) 645-5530 Web – Facebook – Twitter CRIBS FOR KIDS: President Pro Tem Priscilla R. Tyson is sponsoring ordinance 0378-2016 to purchase portable cribs for the Department of Public Health. Columbus Public Health, as recommended by the Greater Columbus Infant Mortality Task Force, has a need to purchase portable cribs to ensure a safe sleep environment for the children of Franklin County. CRIME PATROL: Councilmember Mitchell J. Brown is sponsoring ORD. 0259-2016 for the Department of Public Safety to enter into a contract with the Community Crime Patrol. Continuing Council’s focus on safe neighborhoods, the area to be patrolled includes The Ohio State University District, Weinland Park, Hilltop, Franklinton, Merion Village Area, Olde Towne East/Franklin Park and Northland/North Linden Area. COMMUNITY PLAYGROUND: Chair of Recreation and Parks committee, Jaiza Page, is sponsoring an ordinance that will enter into contract with Playworld Midstates for the design, site preparation and supervision of a community built playground at the Marion Franklin Community Center. By using the The KaBoom! Community Build Model, community volunteers will plan for, design and build the playground. EMPLOYEE TRAINING: Councilmember Elizabeth Brown is sponsoring ordinance 0302-2016 to continue investing in employee professional development. This legislation will enhance the training supplies, equipment and course offerings at the Citywide Training and Development Center. TECHNOLOGY IMPROVEMENTS: Councilmember Michael Stinziano is supporting ordinance 0201-2016, entering into the third year of an agreement with Lucity, Inc. This application system is integrated with Columbus’ 311 app, City GIS, and other City of Columbus organization-wide applications. -

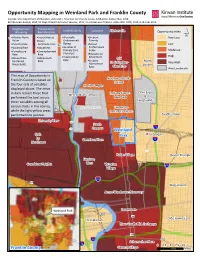

Opportunity Mapping in Weinland Park and Franklin County

Opportunity Mapping in Weinland Park and Franklin County Sources: Ohio Department of Education, 2010-2011; American Community Survey, 2006-2010; Justice Atlas, 2008; ESRI Business Analyst, 2010; US Dept of Health & Human Services, 2010; County Business Patterns, 2006-2009; COTA, 2010; HUD User, 2010 Neighborhood Transportation Health & Safety EducatioSnouth Clintonville & Housing & Employment Opportunity Index East Linden Up•pMeerd Aiarnli Hnogmtoen •Transit Access •Medically •Student Very Low Value •Mean Underserved Poverty •Poverty Rate Commute Time RiverRvaiteinwg •School Low •Number of Performance •Vacancy Rate •Job Access Moderate •Foreclosure •Unemployment Primary Care Index Providers Rate Rate •Educational High •Rate of Cost- •Job Growth •Incarceration Attainment Old Burdened Rate Rate •Student N. Columbus- North Very High Attendence Households Glen Echo Linden Rate Area Landmarks This map of Opportunity in Northwood Park- Franklin County is based on SoHud the four sets of variables North Campus displayed above. The areas in dark red are those that Indiana Forest- Ohio Expo West & Main Campus & performed the best across Iuka Park Fairgrounds these variables among all census tracts in the county, Ohio State University University- while the light yellow areas Indianola Terrace performed the poorest . South Linden University View 315 South Campus 71 315 Weinland Fifth Milo-Grogan by Park Dennison Place 71 Northwest 3 Italian Village Devon Triangle Harrison West Victorian Grandview Heights 670 Village 670 33 King-Lincoln North Franklinton -

Incentive Analysis for Existing Community Reinvestment Areas and Neighborhood Investment Districts in Columbus, Ohio

Incentive Analysis for Existing Community Reinvestment Areas and Neighborhood Investment Districts in Columbus, Ohio: For: Mr. Quinten Harris, JD MPA Deputy Direct, Jobs & Economic Development City of Columbus, Department of Development Ms. Hannah Reed Assistant Director City of Columbus, Department of Development Effective Date: May 30, 2018 VSI Job Reference Number: 14795NY Phone: (614) 224-4300 Fax: (614) 225-9505 1310 Dublin Rd., Columbus, Ohio 43215 VSInsights.com CRA and NID Incentive Analysis Columbus, OH Table of Contents Introduction I Summary of Indicators (by CRA and NID) Outperforming the City of Columbus Baseline II Total Number of Indicators (by CRA & NID) Outperforming the City of Columbus Baseline II-1 Designation Criteria Classification by CRA and NID II-2 Individual Community Reinvestment Area (CRA) and Neighborhood Investment District (NID) Profiles III Fifth by Northwest Community Reinvestment Area III-1 Franklinton Neighborhood Investment District III-5 Hilltop Neighborhood Investment District III-9 Linden Neighborhood Investment District III-13 Livingston and James Community Reinvestment Area III-17 Milo-Grogan Community Reinvestment Area III-21 Near East Side Neighborhood Investment District III-25 North Central Community Reinvestment Area III-29 Short North Community Reinvestment Area III-33 Southside Neighborhood Investment District III-37 Weinland Park Community Reinvestment Area III-41 Summary of Indicators (by CRA and NID) Outperforming the City of Columbus Baseline IV Population (2000, 2010, 2012 and 2017) IV-1 Percent Change in Population from 2012 to 2017 IV-2 Median Household Incomes (2000, 2010, 2012 and 2017) IV-3 Percent Change in Median Household Incomes from 2012 to 2017 IV-4 Poverty Rates (2016) IV-5 Median Rent Per Square Foot (2012 and 2017) IV-6 Percent Change in Median Rent Per Square Foot from 2012 to 2017 IV-7 Housing Vacancy Rates (2017) IV-8 Mortgage Foreclosure Rate (May 2018) IV-9 Qualifications V Table of Contents Incentive Analysis Columbus, OH I.