Urbanization in Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Study on Economic Partnership Projects in Developing Countries in Fiscal Year 2017

STUDY ON ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP PROJECTS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES IN FISCAL YEAR 2017 STUDY ON YANGON INNER RING ROAD CONSTRUCTION PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR Final Report February 2018 Prepared for: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Prepared by: JFE Engineering Corporation Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. Metropolitan Expressway Company Limited Marubeni Corporation Preface This report is prepared by JFE engineering Corporation, Oriental Consultants Global Co. Ltd., Metropolitan Expressway Company Limited and Marubeni Corporation as the result of “Study on the Economic Partnership Projects in Developing Countries in Fiscal Year 2017” for the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. The study presented here is titled “Study on YANGON INNER RING ROAD CONSTRUCTION PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR”. The project aims to construct 24km long motor way along with its O&M in Yangon, former capital city of Myanmar, by PPP scheme. As in other Asian major cities, in Yangon the number of vehicles has increased sharply with the rapid population increase. As a result, traffic congestion occurs through daytime although it only occurred in the morning and evening commuting time become a big social problem. This survey is to study the countermeasure for this urgent issue and contributes to the development of Yangon. We hope this report will contribute to the realization of the project mentioned above and serve as reference for the related organizations and parties in Japan. February 2018 JFE Engineering Corporation Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. Metropolitan Expressway Company Limited Marubeni Corporation Project Area Map Source: Study Team by Internet Information Table of Contents Preface Project Area Map Table of Contents Table list Figure List Abbreviations Page Executive Summary (1) Outline of the Project ........................................................................................................................................ -

Appendix 6 Satellite Map of Proposed Project Site

APPENDIX 6 SATELLITE MAP OF PROPOSED PROJECT SITE Hakha Township, Rim pi Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village A6-1 Falam Township, Webula Village Tract, Chin State Kim Mon Chaung Village A6-2 Webula Village Pa Mun Chaung Village Tedim Township, Dolluang Village Tract, Chin State Zo Zang Village Dolluang Village A6-3 Taunggyi Township, Kyauk Ni Village Tract, Shan State A6-4 Kalaw Township, Myin Ma Hti Village Tract and Baw Nin Village Tract, Shan State A6-5 Ywangan Township, Sat Chan Village Tract, Shan State A6-6 Pinlaung Township, Paw Yar Village Tract, Shan State A6-7 Symbol Water Supply Facility Well Development by the Procurement of Drilling Rig Nansang Township, Mat Mon Mun Village Tract, Shan State A6-8 Nansang Township, Hai Nar Gyi Village Tract, Shan State A6-9 Hopong Township, Nam Hkok Village Tract, Shan State A6-10 Hopong Township, Pawng Lin Village Tract, Shan State A6-11 Myaungmya Township, Moke Soe Kwin Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-12 Myaungmya Township, Shan Yae Kyaw Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-13 Labutta Township, Thin Gan Gyi Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Protection Dike Rainwater Pond (New) : 5 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) : 20 Facilities A6-14 Labutta Township, Laput Pyay Lae Pyauk Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-15 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road Irrigation Channel Rainwater Pond (New) : 2 Facilities Rainwater Pond (Existing) Hinthada Township, Tha Si Village Tract, Ayeyarwady Region A6-16 Symbol Facility Proposed Road Other Road -

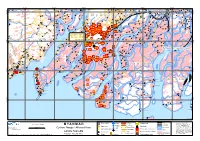

Recent Flood Condition in Myanmar

Flood Inundation Analysis and Flood Assessment for Nyaungdon Township Presented by Hydrological Division Department of Meteorology and Hydrology Ministry of Transport and Communication MICC 2, Nay Pyi Taw The presentation will cover Recent flood condition Location and background of study area Data sources RRI Model structure overview Model simulation Result and discussion Conclusion and recommendation 2 Recent flood condition in Myanmar Recently, Myanmar had to face the Meteorological and Hydrological hazards. Flood occurred in 13 region due to the bad weather impact. The strengthen monsoon and cyclone KOMEN caused the water related disaster as landslide, debris flow and flood(riverine flood & flash flood). 3 Cloud covered the whole country by Cyclone KOMEN 4 Flood affected areas and affected people Source: RRD 5 Estimate inundation areas in Myanmar(July-August 2015) . Software : RRI Model . DEM : USGS Hydroshed (grid size 2Km) . Rainfall : 3B42RT (Satellite) . Model parameter : Standard value 6 Ayeyarwaddy Bawle Lat: 16.85 deg to 17.21deg Long: 95.55 deg to 95.90 deg Population: 215906 Area: 899.72Km2 Village: 41 Pan Hlaing Source: GAD, Nyaungdon 7 8 Destroyed farmland in acres (2015-flood event) 9 Field trip survey to Nyaung Don City area (18.5.2016) 10 Final meeting of ADB 8456: Part II Flood Management at Royal ACE Hotel, Nay Pyi Taw 11 Field trip survey to Nyaung Don City area (23rd-26th .1.2017) 12 13 http://floodobservatory.colorado.edu/14 Highest Water level records at Pan Hlaing River, Nyaung Don Site Data Sources: Department of Irrigation and Water Utilization Management, Nyaung Don 15 Overview of model structures 16 Input data and parameter setting The following data are used to run the RRI- Model • 15 sec DEM (HydroSHEDS) • Approx. -

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1

Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 2 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 3 4 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 စ Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 5 6 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 7 8 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 9 10 Pathein University Research Journal 2017, Vol. 7, No. 1 Spatial Distribution Pattrens of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City Tin Tin Mya1, May Oo Nyo2 Abstract Pathein City is located in Pathein Township, western part of Ayeyarwady Region. The study area is included fifteen wards. This paper emphasizes on the spatial distribution patterns of these schools are analyzed by using appropriate data analysis methods. This study is divided into two types of schools, they are governmental schools and nongovernmental schools. Qualitative and quantitative methods are used to express the spatial distribution patterns of Basic Education Schools in Pathein City. Primary data are obtained from field surveys, informal interview, and open type interview .Secondary data are collected from the offices and departments concerned .Detailed facts are obtained from local authorities and experience persons by open type interview. Key words: spatial distribution patterns, education, schools, primary data ,secondary data Introduction The study area, Pathein City is situated in the Ayeyarwady Region. The study focuses only on the unevenly of spatial distribution patterns of basic education schools in Pathein City . -

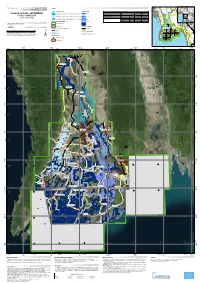

Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area Delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R

Nepal (!Loikaw GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR130 I Legend r n r India China e Product N.: 16IRRAWADDYDELTA, v2, English Magway a Rakhine w Bangladesh e a w l d a Vietnam Crisis Information Hydrology Consequences within the AOI on 09, 10, 11/08/2015 d Myanmar S Affected Total in AOI y Nay Pyi Taw Irrawaddy Delta - MYANMAR Flooded Area delineation 11/08/2015 11:46 UTC River R ha 428922,1 i v Laos Flooded area e ^ r S Flood - 01/08/2015 Flooded Area delineation 10/08/2015 23:49 UTC Stream Estimated population Inhabitants 4252141 11935674 it Bay of ( to Settlements Built-up area ha 35491,8 75542,0 A 10 Bago n Bengal Thailand y g Delineation Map e Flooded Area delineation 09/08/2015 11:13 UTC Lake y P Transportation Railways km 26,0 567,6 a Cambodia r i w Primary roads km 33,0 402,1 Andam an n a Gulf of General Information d Sea g Reservoir Secondary roads km 57,2 1702,3 Thailand 09 y Area of Interest ) Andam an Cartographic Information River Sea Missing data Transportation Bay of Bengal 08 Bago Tak Full color ISO A1, low resolution (100 dpi) 07 1:600000 Ayeyarwady Yangon (! Administrative boundaries Railway Kayin 0 12,5 25 50 Region km Primary Road Pathein 06 04 11 12 (! Province Mawlamyine Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 46N map coordinate system Secondary Road 13 (! Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± Settlements 03 02 01 ! Populated Place 14 15 Built-Up Area Gulf of Martaban Andaman Sea 650000 700000 750000 800000 850000 900000 950000 94°10'0"E 94°35'0"E 95°0'0"E 95°25'0"E 95°50'0"E 96°15'0"E 96°40'0"E 97°5'0"E N " 0 ' 5 -

D E D a Y E K Y a I K L a T B O G a L E Pyapon Mawlamyinegyun

95°30’0"E 95°40’0"E 95°50’0"E TAUNGBOGON NGA-EINDAN KWINGYAUNG KALAGYI KALAUNGBON DAUNGGYI MIGYAUNGAING YWA-BIT YWAHAUNG MAYAN KYUNGYA MAYAN TA M AN G YI KALAGYIWA YOKSAING GYOWA GONDANGALE KUNBINGYAUNG MALAGON NPOPON YWATHIT KYONSOK ONGYI TA M U T TALOKSEIK KUNGYANGON TAUNGALE MINHLAZU MAYAN AMAWCHOK KYAUKYEZU KYAGON THEGON TA I N G KWI HTEINGAING NGE-EINZU KYONKYAIK KYONBE LE-EINZU AINGBON TEIKPWIN TANYINGON Mawlamyinegyun TA M O N KYONTA MEZALIGAN HPONYOZEIKASU KYIBINZU SHANGWIN NYAUNGGYAUNG Kyaiklat TA M AWG Y I LINDAING KANZU TA M AN MINHLA-ASU HNGETTAW TETTEZU THEINGONGYI HKANAUNG KYAGAYET YWATHIT-ASHE TA M AW- ATE T CHAUKEINDAN MAYITKA-KWIN KUNBIN THALEIK KANZU MA-UBIN KULAN-MYAUK THAYAGON HTALUNZU INDU DABAYIN MINGAN KULAN-TAUNG NYINAUNG NANGYAUNG MYINGAGON HKANAUNG-ASHE AKHA KULAN-MYAUK LAMUGYI SHANZU AGEGYI PETALA BOGALE TEINBIN BONTHALEIK DANIZU KOTHETSHE-ASU ASIGALE TA M AN KWI N TAW H KA M AN KYONDU KYONTHUT-ASHE HSATTHABUGON 16°20’0"N KYUNGYA THANLAIK PETTETAUNG 16°20’0"N THE-EIN KAYINZU HMAWBI HMAWAING TAW H L A WEGYI HAINGSI YWATHIT THAKAN CHAUNGDWIN TA M AN G YI GWEDAAUKKON LETPYAUNGBAING THEGONGALE YWADANSHE THITTOGYAUNG PAYA GY IGO N POYAUNG THE-EINGYAUNGZU THAYAGON KAYINZU SAYAYO-ASU AKYI MAYANGWA MEZALIGYAUNG ONBIN PA-AUNGGYI PANGADAT SHANGWIN KALAGYICHAUNG TEBINZEIK THAKAN DANIBAT KYONKU KWIN KHAMAPO UDO KONDAN YEGYAW-YWA POSHWELON-ASU MANGEGALE KANZU KYAUNGZU DedayeTA N YI PAYA GYAUNG MAGYIDAN DANIPAT EINYAGYI KUNTHICHAUNGWA KYONPA TA M AN NEYAUNGGON KYONTHUT-MYAUK APYAUNG SITKON KOTAIKKYI-ASU PAUK PA NBY UZU MYINGAGON -

Social Assessment for Ayeyarwady Region and Shan State

AND DEVELOPMENT May 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR AYEYARWADY REGION AND SHAN STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition 1 Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement May 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 10 List of BOXES ................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Introduction and Background....................................................................................................... 11 1 Objectives of the Social Assessment ................................................................................................11 2 Project Description ..........................................................................................................................11 3 Relevant Country and Sector Context..............................................................................................12 3.1 -

B O G a L E Mawlamyinegyun Wakema Labutta M Y a U N G M Y a N

94°20’0"E 94°30’0"E 94°40’0"E 94°50’0"E 95°0’0"E 95°10’0"E CHAUNGAUK KYETTHUNGYAUNG DAYIN-GAUK PEINNEGYAUNG YEGYAN KONGALE TUMYAUNG ONBINZEIKPONSOGYI BYAINGDAUNG YWATHIT NYAUNGLAN UDOCHAUNG MEZALI-UDO YEGYAWGYI KYAUKKWE KYAGWIN HM ANGU KWINBAT KYAUKPON POBYE KANGYAUNG THONGWA KYAWNU-UDO HGETKYIDAN SHWEKA YWATHITGALE NGAYOKTHI THAYETKON LABUTPYE SHWEZAN THEGYAUNG SEIKKYI YWATHITGALE KYAUKPYAGALE PAWDAW MU YWATHIT MEZALI MANKALA THAYETCHAUNG LEGWA TIKOGAING KYAUKKWE BEBAUK KYONLATA KYUNTHIT WakemaNYAUNGGYAUNG KANGON LE-EINDAN KALAMATAUNG TA U KS H A PACHAUNG KYEINNI SABYUZU SHANZU THALIGAGON HM ANGU SABYUZU TALAPHIKYUN HTANNYETCHAUNG ALEGYAUNG AUNGHLAING 16°20’0"N KINMONZEIK NONKYUN-AUKSU 16°20’0"N MAUNG-BI KYEINGONGYI THAYEGYAUNG BUDINGYAUNG ZAYATCHAUNGBYA PEIKTA DUNWAING PEINGYAUNG YAKAINGGON THINGANBYU YAMALNW KYONLATA-AWA MYINDALIN LEIKABO KYIGYAUNG POLAUNG KOKKO KANGYAUNG KUNGWIN THAINGGYAUNG MyaungmyaLEBYAUK KYONLAMU MYATTHA-UDO POYANGON KANAZOGYAUNG NYAUNGBINTHA KWINGYAUNG MINGON MYITKYO SETKON NGADA NTAY TEBIN MOGAUNG MAYANGON EINMAGON KYUDAW THAUNGBON KYONLATA BYAUNGBYAN PO-SHWE HLAW MEZALI THEGYAUNG MYAHPUGYAUNG PYINMAGYAUNG-WA KHAYEGON KYAGAN KYAGAN PYAKEIK SE-EINZU KYAGYAUNG NGAYANGAUNGDO KYUNGALE MWEHAUK THEGON SAMALAUK CHAUNGBYA MABE POTILUT CHAUNGBYA KATHABAUNG AWABEIK CHAUNGGWEGYI AUNGHLAING NAT-HMU KYUTKON CHAUNGGWE KYAUKGYI ALEYWA THINDAWGYI PEIKTAGYI SHAUKCHAUNG YWATHIT MAYANGON KYAUKPYAKWIN BAWINSU KYAUKPYA LEIKPOK KYUNGYAUNG THAHTEGON THAMA AH-KA YWATHIT YEGYOGON HLAINGBON SANGYIGON THAYETPINGWIN KABALU NY EINU DIPAYON -

Reviewing of Political Dialogue Framework : Steps to All Inclusiveness

Vol. III, No. 120, 11th Waxing of Wagaung 1378 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Sunday, 14 August, 2016 Tens of thousands 2nd batch of detained State of fish Myanmar workers Counsellor to released into returns to Yangon pay official visit Yayzin Dam from Malaysia PAGE 9 PAGE 2 to China PAGE 3 FLOOD PROTECTION VP pledges to assist in rehabilitation of flood victims in Ayeyawady Region VICE President U Henry Van Thio pledged to assist in the reha- bilitation of flood-affected people in the Ayeyawady Region and stressed the need to step up pre- paredness to fight such disasters in future. At a meeting with flood-af- fected people sheltering at a monastery in Nyaungdon the vice president called on locals to co- operate with the government in disaster preparedness matters as the country is experiencing flood- ing nearly every year. During his tour of Ay- eyawady Region, Vice Pres- ident U Hnery Van Thio vis- ited flood-affected people sheltering at temporary relief camps in Ngathaingchaung, Lay- myatnar, Hinthada, Zalun, Danu- byu and Nyaungdon and present- ed aid to them. The vice president also in- spected dams and dykes. The flooding hit nine- teen townships in the region, displacing more than 120,000 residents. Vice President U Henry Van Thio assists in preparedness to the flooding in Danubyu, Ayeyawady Region. PHOTO: MNA Local authorities have estab- lished more than 680 shelters for submerged more than 202,000 Ayeyawady Region. Meawhile, three rivers over the next two days, according the peoples in the areas affected acres of farmland with paddy The flooding has also forced which are currently exceeding the Department of Meteorolo- by flooding. -

The Provision of Public Goods and Services in Urban Areas in Myanmar: Planning and Budgeting by Development Affairs Organizations and Departments

The Provision of Public Goods and Services in Urban Areas in Myanmar: Planning and Budgeting by Development Affairs Organizations and Departments Michael Winter and Mya Nandar Thin December 2016 Acknowledgements The authors thank the many Development Affairs Organization (DAO) officials in Shan, Mon and Kayin States and in Ayeyarwady and Tanintharyi Regions who discussed their work and generously provided access to DAO documentation. The authors would also like to thank members of Township Development Affairs Committees (TDACs) who contributed to the production of this report. In addition, the authors thank the staff of The Asia Foundation and Renaissance Institute for providing invaluable logistical and administrative support. About the Authors Michael Winter, the lead author of the report, over the last twenty years, has worked as a consultant on local government and local development issues in Asia and Africa. His main clients have included UNCDF, UNDP, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, SDC, and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID). Mya Nandar Thin is a Program Associate at Renaissance Institute and provides support in the planning and implementation of research and advocacy activities lead by the Public Financial Management Reform team. About The Asia Foundation and Renaissance Institute The Asia Foundation is a nonprofit international development organization committed to improving lives across a dynamic and developing Asia. Informed by six decades of experience and deep local expertise, our programs address critical issues affecting Asia in the 21st century—governance and law, economic development, women’s empowerment, environment, and regional cooperation. In addition, our Books for Asia and professional exchanges are among the ways we encourage Asia’s continued development as a peaceful, just, and thriving region of the world. -

Laboratory Aspects in Vpds Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

Laboratory Aspect of VPD Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation Dr Ommar Swe Tin Consultant Microbiologist In-charge National Measles & Rubella Lab, Arbovirus section, National Influenza Centre NHL Fever with Rash Surveillance Measles and Rubella Achieving elimination of measles and control of rubella/CRS by 2020 – Regional Strategic Plan Key Strategies: 1. Immunization 2. Surveillance 3. Laboratory network 4. Support & Linkages Network of Regional surveillance officers (RSO) and Laboratories NSC Office 16 RSOs Office Subnational Measles & Rubella Lab, Subnational JE lab National Measles/Rubella Lab (NHL, Yangon) • Surveillance began in 2003 • From 2005 onwards, case-based diagnosis was done • Measles virus isolation was done since 2006 • PCR since 2016 Sub-National Measles/Rubella Lab (PHL, Mandalay) • Training 29.8.16 to 2.9.16 • Testing since Nov 2016 • Accredited in Oct 2017 Measles Serology Data Measles Measles IgM Measles IgM Measles IgM Test Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 1766 1245 452 69 2012 1420 1182 193 45 2013 328 110 212 6 2014 282 24 254 4 2015 244 6 235 3 2016 531 181 334 16 2017 1589 1023 503 62 Rubella Serology Data Rubella Test Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 425 96 308 21 2012 195 20 166 9 2013 211 23 185 3 2014 257 29 224 4 2015 243 34 196 13 2016 535 12 511 12 2017 965 8 948 9 Measles Genotypes circulating in Myanmar 1. Isolation in VERO h SLAM cell line 2. Positive culture shows syncytia formation 3. Isolated MeV or sample by PCR 4. Positive PCR product is sent to RRL for sequencing 5.