Will All of You Stop Being A-Holes, Please?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loss and Grief Manual

LOSS & GRIEF: A manual to help those living with ALS, their families, and those left behind. Mourn not just for the loss of what was but also for what will never be. And then gently, lovingly let go. Copyright © application pending 2007 by The ALS Association, St. Louis Regional Chapter All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Special Acknowledgement to Ms. Jan Korte-Brinker, TKS Graphics, Highland, Illinois for assisting with the design of the front cover. The ALS Association, St. Louis Regional Chapter is dedicated to improving the quality of life for those affected by Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, educating the community, and supporting research. To learn more about the services provided through The ALS Association, St. Louis Regional Chapter in Eastern Missouri as well as Central and Southern Illinois: visit our website at www.alsa-stl.org Table of Contents I. Patients with ALS II. Adults, Spouses, and Caregivers III. Parents and Caregivers of Children ▲ Children – 12 and under ▲ Teenagers – 13-18 ▲ Young Adults – 18-25 ▲ - pullout sections for parents to give to children LOSS AND GRIEF As you deal with your diagnosis of ALS and its effects on your life, you and your family will be confronted with numerous changes and losses. You will face the loss of physical abilities coupled with changes in your role and responsibilities within your family and your community. In addition, you will be facing the inevitable loss of life, while trying to understand and reconcile the experience of having ALS. -

Billboard #1 Records

THE BILLBOARD #1 ALBUMS COUNTRY ALBUM SALES DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (1) 5/11/19 1 1. SCOTT, Dylan Nothing To Do Town (EP) Curb HEATSEEKER ALBUMS DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (1) 7/8/95 1 1. PERFECT STRANGER You Have The Right To Remain Silent Curb 77799 (1) 11/3/01 1 2. HOLY, Steve Blue Moon Curb 77972 (1) 5/21/11 1 3. AUGUST, Chris No Far Away Fervent/Curb-Word 888065 MUSIC VIDEO SALES DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (28) 5/8/93 1 1. STEVENS, Ray Comedy Video Classics Curb 77703 (6) 5/7/94 1 2. STEVENS, Ray Live Curb 77706 TOP CATALOG COUNTRY ALBUMS DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (1) 6/15/91 1 1. WILLIAMS, Hank Jr. Greatest Hits Elektra/Curb 60193 (2) 8/21/93 1 2. JUDDS, The Greatest Hits RCA/Curb 8318 (26) 6/19/99 1 3. MCGRAW, Tim Everywhere Curb 77886 (18) 4/1/00 1 4. MESSINA, Jo Dee I'm Alright Curb 77904 (1) 8/17/02 1 5. SOUNDTRACK Coyote Ugly Curb 78703 (54) 12/7/02 1 6. MCGRAW, Tim Greatest Hits Curb 77978 (2) 1/19/08 1 7. MCGRAW, Tim Greatest Hits, Vol. 2: Reflected Curb 78891 (4) 6/16/11 1 8. MCGRAW, Tim Number One Hits Curb 79205 TOP CHRISTIAN ALBUMS DEBUTPEAK ARTIST TITLE LABEL SEL# (35) 9/27/97 1 1. RIMES, LeAnn You Light Up My Life: The Inspirational Album Curb 77885 (35) 10/7/01 1 2. P.O.D. Satellite Atlant/Curb-Word 83496 (5) 6/8/02 1 3. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Skillet Hero Download Mp3

Skillet Hero Download Mp3 Skillet Hero Download Mp3 1 / 3 2 / 3 Skillet Hero The Legion Of Doom Remix Awake And Remixed EP VIDEO HD Official New Song 2011. play. download. Skillet Hero Official Video mp3.. mp3 download. 4.7M . skillet sick of it official video.mp3 . Hero Mp3 Lagu Video Mp4 Hero hero skillet mp3 ﺗﻨﺰﻳﻞ - Mp3 (6.40 MB) Download. Lirik lagu serta video hero mp4 atau 3gp.. hero skillet mp3 download mp3 Download Skillet Hero Ringtone submitted by Tushar in Music ringtones category. Total downloads so ..ﺩﻧﺪﻧﻬﺎ , download mp4 far: 1933.. Skillet - Awake download free mp3 flac. , Skillet, Awake (CD, Album, Enh), Atlantic, Ardent Records, , US, , Skillet. Download I Can Be Your Hero Baby Mp3 Download Skull Mp3. Song Details. Title: Skillet - Hero (Official Video); Uploader: Atlantic Records; Duration: 03:17 .... ... Gta San Andreas Cleo Pc Download, Download Guitar Hero 5 Skillet Ps2 Via ... Line input jack les you connect your laptop, tablet, smartphone, or MP3 player ... skillet hero skillet hero, skillet hero lyrics, skillet hero mp3 download, skillet hero female singer, skillet hero chords, skillet hero tab, skillet hero live, skillet hero roblox id, skillet heroes never die, skillet hero 1 hour Hero (Skillet song) Download Lagu Skillet Burn It Down mp3 for free (03:17). ... Skillet skillet hero, download audio mp3 skillet hero, 128kbps skillet hero, full hq ... skillet hero mp3 download Skillet Monster (Official Video) - Download MP3 Online - Convert Youtube Video to mp3 instantly #mp3converter #mp3download #downloadmp3 - Skillet ... skillet hero chords Listen to Skillet - Hero Instrumental and write some lyrics on RapPad - featuring a lyrics editor with built in syllable counter, rhyming dictionary ... -

XS March 2020 Update

XS March 2020 Update Artist Song Title Artist Song Title 3 Seconds of Summer Teeth What I Know Now 311 Creatures (For A While) Beyonce Spirit AJR Sober Up Bieber, Justin Yummy Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Blue, Jonas & Theresa Rex What I Like About You Other Side, The Bridges, Leon Beyond (Instrumental Version) Brightman, Sarah & Hot I Lost My Heart to a Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Gossip Starship Trooper Camouflage Hat Brothers Osbourne 21 Summer (Instrumental Version) Brown, James Payback, The Got What I Got Brown, Kane For My Daughter Got What I Got For My Daughter (Instrumental Version) (Instrumental Version) Andress, Ingrid Both Bryan, Luke Cold Beer Drinker Both (Instrumental What She Wants Tonight Version) What She Wants Tonight Lady Lake (Instrumental Version) Lady Lake (Instrumental Buble, Michael Fever Version) Cabello, Camila Living Proof Arizona Zervas Roxanne Cabello, Camilla Shameless Arthur, James You Deserve Better Capaldi, Lewis Before You Go Ballerini, Kelsea Better Luck Next Time Someone You Loved Club Cash, Johnny I Won't Back Down Club (Instrumental Cassidy, Eva & David Gray You Don't Know Me Version) Cave, Nick & the Bad Henry Lee Banderas, Antonio Cancion Del Mariachi Seeds & PJ Harvey Bareilles, Sara I Choose You Celeste Strange Sweet as Whole Chesney, Kenny Tip of my Tongue Barrett, Gabby I Hope Cinnamon, Gerry Bonny, The Bastille Quarter Past Midnight Clarkson, Kelly Underneath the Tree Bastille & Alessia Cara Another Place Clean Bandit & Demi Solo Batey, Joey Toss a Coin to Your Lovato Witcher Clemmons, Riley -

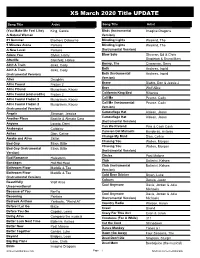

XS March 2020 Title UPDATE

XS March 2020 Title UPDATE Song Title Artist Song Title Artist (You Make Me Feel Like) King, Carole Birds (Instrumental Imagine Dragons A Natural Woman Version) 21 Summer Brothers Osbourne Blinding Lights Weeknd, The 5 Minutes Alone Pantera Blinding Lights Weeknd, The A New Level Pantera (Instrumental Version) Adore You Styles, Harry Blow Solo Sheeran, Ed & Chris Afterlife Steinfeld, Hailee Stapleton & Bruno Mars Bonny, The Ain't A Train Jinks, Cody Cinnamon, Gerry Both Ain't A Train Jinks, Cody Andress, Ingrid (Instrumental Version) Both (Instrumental Andress, Ingrid Version) Alive Daughtry Brave All is Found Frozen 2 Diablo, Don & Jessie J Bros All is FOund Musgraves, Kacey Wolf Alice California King Bed All is Found (end credits) Frozen 2 Rihanna Call Me All is Found Frozen 2 Musgraves, Kacey Pearce, Carly Call Me (Instrumental All is Found Frozen 2 Musgraves, Kacey Pearce, Carly (Instrumental Version) Version) Camouflage Hat Angels Simpson, Jessica Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Another Place Bastille & Alessia Cara Aldean, Jason (Instrumental Version) Anyone Lovato, Demi Can We Pretend Pink & Cash Cash Arabesque Coldplay Cancion Del Mariachi Banderas, Antonio Ashes Dion, Celine Change My Mind Dion, Celine Awake and Alive Skillet Chasing You Wallen, Morgan Bad Guy Eilish, Billie Chasing You Wallen, Morgan Bad Guy (Instrumental Eilish, Billie (Instrumental Version) Version) Circles Post Malone Bad Romance Halestorm Club Ballerini, Kelsea Bandages Hot Hot Heat Club (Instrumental Ballerini, Kelsea Bathroom Floor Maddie & Tae Version) Bathroom -

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT

Maximum Ride T H E ANGEL EXPERIMENT James Patterson WARNER BOOKS NEW YORK BOSTON Copyright © 2005 by Suejack, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Warner Vision and the Warner Vision logo are registered trademarks of Time Warner Book Group Inc. Time Warner Book Group 1271 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020 Visit our Web site at www.twbookmark.com First Mass Market Edition: May 2006 First published in hardcover by Little, Brown and Company in April 2005 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. Cover design by Gail Doobinin Cover image of girl © Kamil Vojnar/Photonica, city © Roger Wood/Corbis Logo design by Jon Valk Produced in cooperation with Alloy Entertainment Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Maximum Ride : the angel experiment / by James Patterson. — 1st ed. p.cm. Summary: After the mutant Erasers abduct the youngest member of their group, the "bird kids," who are the result of genetic experimentation, take off in pursuit and find themselves struggling to understand their own origins and purpose. ISBN: 0-316-15556-X(HC) ISBN: 0-446-61779-2 (MM) [1. Genetic engineering — Fiction. 2. Adventure and adventurers — Fiction.] 1. Title. 10 9876543 2 1 Q-BF Printed in the United States of America For Jennifer Rudolph Walsh; Hadley, Griffin, and Wyatt Zangwill Gabrielle Charbonnet; Monina and Piera Varela Suzie and Jack MaryEllen and Andrew Carole, Brigid, and Meredith Fly, babies, fly! To the reader: The idea for Maximum Ride comes from earlier books of mine called When the Wind Blows and The Lake House, which also feature a character named Max who escapes from a quite despicable School. -

Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM

Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message – August 16, 2019 – 8:30PM a project of Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere for SOMA Summer 2019 at La Morenita Canta Bar (Puente de la Morena 50, 11870 Ciudad de México, MX) karaoke provided by La Morenita Canta Bar songbook edited by Angel Nevarez and Valerie Tevere ( ) 18840 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash 10274 (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & Diamonds 00005 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 17636 (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 15910 (I Want To) Thank You Freddie Jackson 05545 (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees 06305 (It's) A Beautiful Mornin' Rascals 19116 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon 15128 (Keep Feeling) Fascination Human League 04132 (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran 05241 (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding 17305 (Taking My) Life Away Default 15437 (Who Says) You Can't Have It All Alan Jackson # 07630 18 'til I Die Bryan Adams 20759 1994 Jason Aldean 03370 1999 Prince 07147 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 18961 21 Guns Green Day 004-m 21st Century Digital Boy Bad Religion 08057 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 00714 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band 01379 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 14375 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 08711 4 Minutes Madonna 08867 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 09981 4 Minutes Avant 18883 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 13317 500 Miles Peter Paul & Mary 00082 59th Street Bridge Song Simon & Garfunkel 00384 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 08937 99 Luftballons Nena 03637 99 Problems Jay-Z 03855 99 Red Balloons Nena 22405 1-800-273-8255 -

Skillet Bio 2013

SKILLET RISE Skillet recently made headlines when their last album, Awake, became one of just three rock albums to be certified platinum in 2012, forming an improbable triumvirate with the Black Keys’ El Camino and Mumford & Sons’ Babel. The news that Skillet had sold more than a million albums in the U.S. came as a shock to all but the band’s wildly diverse horde of fans, male and female, young and old—known as Panheads—whose still-swelling ranks now officially number in the seven-digit range. This remarkable achievement was announced just as Skillet was putting the finishing touches on their eagerly awaited follow-up album, Rise (Atlantic/Word). Unwilling to stand pat or rest on their laurels, the band—lead vocalist/bassist John Cooper, guitarist/keyboardist Korey Cooper (John’s wife), drummer/duet partner Jen Ledger and lead guitarist Seth Morrison, making his first appearance on record with Skillet—continue to explore new terrain on Rise, expertly produced by Howard Benson, who previously helmed the mega- successful Awake. Eager for new challenges, Cooper threw himself into collaborative songwriting to a far greater degree than ever before, co-writing the uplifting title song and the lacerating first single “Sick of it” with Scott Stevens, founder/leader of the L.A.-based Exies, while teaming with Nashville songsmiths Tom Douglas and Zac Maloy on the timely and anthemic “American Noise,” which Cooper considers to be the strongest song Skillet has yet recorded. On “American Noise” and the joyous “Good to Be Alive,” the band explores new stylistic territory, bringing an element of heartland rock into their aggressive, theatrical approach. -

Skillet Collide Album Download Collide

skillet collide album download Collide. John L. Cooper has finally hit his stride with Skillet. Collide is a disc that chugs along with guitars out front, screaming vocals, and a raw intensity that strips the band of its electronic nuances. Opting for a much more aggressive sound, the band leans on guitar riffs while synths are more tastefully added. Songs like "Forsaken" and "Savior" are perfect examples of unadulterated rock bliss. Even when the band veers away from the heaviness à la the well-placed orchestration on "Collide," the meat of the tune still ends up rocking out. With this disc, Skillet takes a firm stance toward honing a sound that is marketed to Generation X. With cuts to back it, they may have found the right vehicle to reach those ears. Skillet collide album download. In an age of re-releases and "special editions" galore, Skillet is the latest to join the throes of album revisitations, offering a CD/DVD "Deluxe Edition" of their hit 2006 record Comatose . For this particular second time around, Comatose is given an additional song to its original eleven- song tracklisting that had been recorded too late to make it onto the original release last year. And in addition to these twelve studio songs, five "acoustic" renditions of tracks featured herein are tacked on at the end. Finally, to round out this re-release, a DVD is added as a second disc that includes four music videos. As a whole, the packaging for Comatose: Deluxe Edition , which boasted new artwork, merely offers a slip cover with new artwork on the front and back, and the actual CD case retains its previous back and front cover. -

1 Theresa Werner

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH ROGER DALTREY AND PETE TOWNSHEND SUBJECT: UCLA DALTREY/TOWNSHEND TEEN & YOUNG ADULT CANCER PROGRAM MODERATOR: THERESA WERNER, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2012 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. THERESA WERNER: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Theresa Werner, and I am the 105th President of the National Press Club. We are the world’s leading professional organization for journalists committed to our profession’s future through our programming and events such as this while fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. To donate to programs offered to the public through our National Press Club Journalism Institute, please visit press.org/Institute. On behalf of our members worldwide, I'd like to welcome our speakers and those of you attending today’s event. Our head table includes guests of our speakers as well as working journalists who are National Press Club members. And if you hear applause in our audience, we’d note that members of the general public are attending so it is not necessarily evidence of a lack of journalistic objectivity. -

Hit `Happens' Gigolo Aunts "The Big Lie" Muzze "Second Time.." Blur "Swamp Song" Blur 'Tender' by Rich Michalowski Stretch Pnncess "Free" Pop Unknown'wrihng It Down

ALTERNATIVE March 26, 1999 R &R 99 NEW MUSIC SPECIALTY SHOWS SPECIALTY SHOW REPORTERS R &R's Exclusive Look At The Cutting Edge Of Alternative Shows and their Top 5 songs listed alphabetically by market WEOX/Albany, NY KDGE/Dallas, TX KROQ/Los Angeles, CA KPNT/St. Louis, MO Download Adventure Club Rodney On The ROO New Music Sunday Sunday8 -11pm Sunday6 -9pm SundaymidnigM -3am Sunday 7-9:30pm Jeff Wade Josh Venable RodneyBingenheimer Les Aamn Hit `Happens' Gigolo Aunts "The Big Lie" Muzze "Second Time.." Blur "Swamp Song" Blur 'Tender' By Rich Michalowski Stretch Pnncess "Free" Pop Unknown'Wrihng It Down.. " Travo'Wrting To..." Kula Shaker "Shower Your Love' Block "Rhinoceros" Underworld "Push Upstairs" Manic Street... "You Stole The Sun" Buck- O- Nine 'Who Are They ?" Asst. Alternative Editor Rentals "Getting By' Apples In Stereo "Seems So' Snoe Bomb "Smudge' Rentals "Getting By" Stardust "Musa Sounds.," Dropkick Murptyh "Perfect Stanger Lute Murderer "Andy Warhol.. "' gallium "Chew" I gave good of Dave Hubble at KFTE/Lafayette a call last week to get his vibe on the new Grand Royal/Capitol release from Ben Lee. Dave is banging the hell out of "Nothing WQBK/Albany, NY WXEG/Dayton, OH KZNZ/Minneapolis, MN Much Happens" on his very diverse music show, End of the World, and feels very strongly Over The Edge The Edge Spin Cycle Freedom Rock Monday midnight -tam Sunday9- 10:30pm Sunday8- 9:30pm the I KXRK/Salt Lake City, UT about single: "The first time heard 'Nothing Much Happens,' I listened to it five times in Kell' McNamara Allen Rant Briaeoake Now Hear This Grand Mal "Whole Latta Nothing" Fountains Of Wayne "Dense' Rentals a row.