War Feels Like War a Film by Esteban Uyarra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faces of Diplomatic Security

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF STATE BUREAU OF DIPLOMATIC SECURITY FACES OF DIPLOMATIC SECURITY YEAR IN REVIEW 2015 On the cover: Highlighted in this OUR MISSION: The Bureau of Diplomatic Security (DS) is the law enforcement and security edition of the DS Year in Review arm of the U.S. Department of State. It bears the core responsibility for providing a safe are nine Diplomatic Security (DS) environment for the conduct of American diplomacy. DS is the most widely represented U.S. personnel representing the diversity law enforcement and security organization in the world and protects people, property, and of skills that help DS fulfill its information at 275 State Department missions around the globe. To achieve this mission, DS is broad law enforcement and a leader in mitigating terrorist threats to American lives and facilities, mounting international security mission. (U.S. Department of State photos) investigations, and generating innovations in cyber security and physical security engineering. BUREAU OF DIPLOMATIC SECURITY YEAR IN REVIEW 2015 02 Message from the Assistant Secretary for Diplomatic Security 05 Embassies: On the 30 Investigating Terror 44 Critical Information Front Lines and Crime • Cyber Defenders..... 44 • Mali Hotel Rescue ...5 • Investigations ....... 30 • The Face of DS: • The Face of DS: • The Face of DS: Chris Buchheit....... 45 Carrington Johnson .. 9 Marcus Purkiss ...... 33 • Command Center.... 46 • Embassy Havana • Most Wanted ....... 35 • The Face of DS: Opens ............. 10 • Field Notes.......... 36 Anthony Corbin .....47 • The Face of DS: • OSAC .............. 48 Michelle Dube....... 11 • Recruiting • Kathmandu and Vetting ......... 50 Earthquake ......... 12 • The Face of DS: Jason Willis ......... 13 • 2015 Attacks ....... -

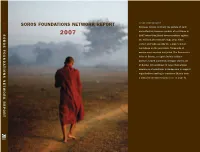

Soros Foundations Network Report

2 0 0 7 OSI MISSION SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT C O V E R P H O T O G R A P H Y Burmese monks, normally the picture of calm The Open Society Institute works to build vibrant and reflection, became symbols of resistance in and tolerant democracies whose governments SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT 2007 2007 when they joined demonstrations against are accountable to their citizens. To achieve its the military government’s huge price hikes mission, OSI seeks to shape public policies that on fuel and subsequently the regime’s violent assure greater fairness in political, legal, and crackdown on the protestors. Thousands of economic systems and safeguard fundamental monks were arrested and jailed. The Democratic rights. On a local level, OSI implements a range Voice of Burma, an Open Society Institute of initiatives to advance justice, education, grantee, helped journalists smuggle stories out public health, and independent media. At the of Burma. OSI continues to raise international same time, OSI builds alliances across borders awareness of conditions in Burma and to support and continents on issues such as corruption organizations seeking to transform Burma from and freedom of information. OSI places a high a closed to an open society. more on page 91 priority on protecting and improving the lives of marginalized people and communities. more on page 143 www.soros.org SOROS FOUNDATIONS NETWORK REPORT 2007 Promoting vibrant and tolerant democracies whose governments are accountable to their citizens ABOUT THIS REPORT The Open Society Institute and the Soros foundations network spent approximately $440,000,000 in 2007 on improving policy and helping people to live in open, democratic societies. -

Of Embedded Journalism: the New Media/Military Relationship by Kylie Tuosto

Stanford Journal of International Relations The "Grunt Truth" of Embedded Journalism: The New Media/Military Relationship By Kylie Tuosto The following article is an exploration and critique of the media-military relationship during times of war. War correspondence has always required a difficult balance of censorship and free press, but with advances in technology and the use of embedded reporters, the problem has grown quite complex. This article argues that in addition to the classic problems of objectivity in war correspondence, the use of embedded reporters has also led to an unprecedented media-military collaboration. A collaborative effort by both the government and the so-called "free press" allows for a pro-war propaganda machine disguised as an objective eyewitness account of the war effort in Iraq. The problems exposed in this article have greater implications for the media and government relationship at large and open { doors for further research and exploration of war correspondence in general. } Longwarjournal.com Embedded journalists make scenes like this one from Jalulah, Iraq accessible to the American public, but at what cost? 20 • Fall/Winter 2008 Embedded Journalsim “We didn’t want to be in bed with the military, tactics, few, if any, questioned US policy. Then, in 1968, but we certainly wanted to be there.” the Tet Offensive changed the media’s perspective on war. – Marjorie Miller, editor of the Los Angeles Times As American troops began to lose significant battles for the first time, the public and press began to challenge America’s merican journalism today has evolved such that decision to continue the fight in Vietnam. -

Thorne Anderson Curriculum Vitae, Updated January 2019

Thorne Anderson Curriculum Vitae, Updated January 2019 EDUCATION 1994-1997 University of Missouri-Columbia; M.A. in Journalism and Mass Communication Master’s Project: A Tale of Two Settlements: Employing Ethnographic Photoelicitation Techniques in the Production of Cross-Cultural Documentary in the Missouri Bootheel Advisory Committee: Dr. Loup Langton, Chair (Photojournalism), Dr. Peter Gardner (Anthropology), and Jan Colbert (Journalism) 1985-1989 Rhodes College; Memphis, Tennessee; B.A. in Psychology POSTGRADUATE EDUCATION 2008-2009 Affiliate to the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University. Studied non-profit organization at the Harvard Business School, American government with David Gergen at the Kennedy School of Government, semiotics with Robin Kelsey, Mozart sonatas with Robert D. Levin, history of documentary film with Scott McDonald, and documentary film production with Robb Moss. Attended once weekly journalism skills and techniques seminars in the Nieman Foundation for Journalism. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2009-Present University of North Texas, Frank W. & Sue Mayborn School of Journalism Mayborn Endowed Chair for Narrative & Multimedia Journalism, August 2018 Associate Professor, Tenured and Promoted to Associate Professor, June 2015 Member of both the Undergraduate and Graduate School Faculties 2015-2016 Foundry Photojournalism Workshops Faculty Member This renowned annual immersive workshop for emerging professionals takes place over one week in July in a different country each year. The faculty includes some of the most esteemed photojournalists working today, including Ron Haviv, Maggie Steber, John Stanmeyer, Andrea Bruce, Paula Bronstein, Stephanie Sinclair, Adriana Zehbrauskas, Jodi Bieber, and Kael Alford. 1996-1998 American University in Bulgaria Full-Time Adjunct Professor of Journalism and Mass Communication, Instructor in fundamentals of journalism, basic reporting, basic and advanced photojournalism, still and video documentary production, visual communication, graphic design and numerous independent studies. -

International ERIKA LARSEN

EXPOSITIONS/EXHIBITIONS . PEDRO UGARTE . ED JONES . LOUISA GOULIAMAKI . ANGELOS e/th TZORTZINIS . ARIS MESSINIS . MATHIAS BRASCHLER . MONIKA FISCHER . JEAN-LOUIS FERNANDEZ . 24 Festival JULIEN GOLDSTEIN . STANLEY GREENE . ROBIN HAMMOND . MASSOUD HOSSAINI . JUSTIN JIN . KRISANNE JOHNSON . BÉNÉDICTE KURZEN . International ERIKA LARSEN . SEBASTIÁN LISTE . JIM LO SCALZO . MANI . DOUG MENUEZ . ILVY NJIOKIKTJIEN . du/of photojournalism RÉMI OCHLIK . PRESSE QUOTIDIENNE . NOËL QUIDU . JOHANN ROUSSELOT . DAMIR SAGOLJ . STEPHANIE SINCLAIR . HADY SY . AMY TOENSING . photojournalisme NIK WHEELER . WORLD PRESS PHOTO 2012 . PROJECTIONS/SCREENINGS . TIMOTHY ALLEN . BRUNO AMSELLEM . JASON ANDREW . JOCELYN BAIN HOGG . JAN BANNING . JONAS BENDIKSEN . ALFREDO BINI . PEP BONET . SARAH CARON . NATHANAEL CHARBONNIER . COLLECTIF SUB.COOP / PICTURE TANK . FABIO CUTTICA . MARCO DAL MASO . WILLIAM DANIELS . CARL DE KEYSER . PHILIPPE DE POULPIQUET . ADAM DEAN . AMÉLIE DEBRAY . JESCO DENZEL . JEAN- PATRICK DI SILVESTRO . MISHA FRIEDMAN . JAN GRARUP . AMNON GUTMAN . ANDY HALL . ROBIN HAMMOND . MARK HENLEY . AARON PRESS HUEY . DIEGO IBARRA SANCHEZ . ED KASHI . DEBRA KELLNER . FRANCE KEYSER . YUNGHI KIM . SRIKANTH KOLARI . EDWIN KOO . MARO KOURI . THORVALDUR ÖRN KRISTMUNDSSON . GERD LUDWIG . PASCAL MAITRE . PAOLO MARCHETTI . LORENZO MELONI . MACIEK NABRDALIK . MICHELE PALAZZI . ALESSANDRO PENSO . SPENCER PLATT . LIZZIE SADIN . MASSIMO KIT SCIACCA . FRANCK SEGUIN . SHOBHA . STEPHANIE SINCLAIR . VLAD SOKHIN . TED SOQUI . GEORGE STEINMETZ . BRENT STIRTON . PATRICE TERRAZ . GALI TIBBON . JONATHAN TORGOVNIK . KADIR VAN LOHUIZEN . STEPHAN VANFLETEREN . MUGUR VARZARIU . JOHN VINK . CRAIG F. WALKER . 2012 ANN-CHRISTINE WOEHRL . DENIS ALLARD . JEAN- CLAUDE COUTAUSSE . OLIVIER LABAN-MATTEI 01. 09 . GUILLAUME BINET . ULRICH LEBEUF. LIONEL CHARRIER . CHARLES OMMANNEY . LAURENCE 16. 09 HAIM . CAROLINE POIRON . JOHN CANTLIE . ROBERT KING . GIULIO PISCITELLI . LAURENT VAN DER STOCKT . GORAN TOMASEVIC . NICOLE pro-week TUNG . MIQUEL DEWEVER-PLANA . -

INK MIAMI,Adam Davies “Boundaries And

INK MIAMI On our trip to Art Basel Miami we planned to attend some of the satellite shows surrounding the convention center. The first one on our list was INK MIAMI because one of our customers, Graphicstudio, was an exhibitor and we wanted to stop by and say hello. It was well worth the trip. INK MIAMI is the antidote to the larger art fairs. It is located in the Dorchester Hotel which is located a few blocks from the convention center where ART BASEL is held. Unlike ART MIAMI and ART BASEL each exhibitor has their own hotel room, which limits the visual clutter of competing exhibitors. The scale of the space and the atmosphere makes it much easier to appreciate the art. It is sponsored by the International Fine Print Dealers Association (IFPDA) and exhibitors are selected from among their members. Since its founding in 2006, the Fair has attracted a loyal following among museum curators and committed collectors of works on paper. There are 15 exhibitors at INK MIAMI and they all serve an important role in the fine art works on paper community. Time constraints did not allow us to talk with each of them individually. In addition to Graphicstudio, we had the opportunity to talk directly with the ones below and we hope to have the privilege of touring their studios in the future. Graphicstudio We have done many projects with Graphicstudio and have toured their studio in Tampa at the University of South Florida so we were familiar with their mission. Artists are invited to work at the studio by invitation. -

THE UNFINISHED REVOLUTION Voices from the Global Fight for Women's Rights

February 28, 2012 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ruth Weiner [email protected] Tel 212-226-8760 Minky Worden [email protected] Tel 212-216-1250 or (m) 1-917-497-054 0 “Women are not free anywhere in this world until all women in the world are free.” ~ Leymah Gbowee, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, 2011 * Publication on March 8, 2012, to coincide with International Women’s Day * THE UNFINISHED REVOLUTION Voices from the Global Fight for Women’s Rights Edited by Minky Worden Foreword by Christiane Amanpour “It’s a time of change in the world, with dictators toppling and new opportunities rising, but any revolution that doesn’t create equality for women will be incomplete. The time has come to realize the full potential of half the world’s population.” ~Christiane Amanpour, from the foreword Women’s rights have progressed significantly in the last two decades, but major challenges remain in order to end gender discrimination as required by international human rights law. The Unfinished Revolution (March 8th, 2012) tells the story of the global struggle to secure basic rights for women and girls, including in the Middle East where the Arab Spring raised high hopes, but where genuine long-term progress in women’s rights remains an uncertainty. More than 30 writers —leading activists, top policymakers, experts in women’s rights, and former victims—have contributed to this anthology. With incisive essays by Nobel Peace Prize laureates Shirin Ebadi and Jody Williams, as well as Mary Robinson, Dr. Hawa Abdi of Somalia, a foreword by Christiane Amanpour, and many other contributors, this book tackles some of the toughest questions and offers bold new approaches to problems affecting hundreds of millions of women. -

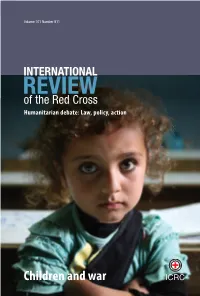

Children And

Children and war 101 Number 911 Volume Volume 101 Number 911 Volume 101 Number 911 Editorial: Childhood in the crossfire: How to ensure a dignified present and future for children affected by war Ellen Policinski and Kvitoslava Krotiuk Interview with Mira Kusumarinai, Executive Director of the Coalition of Civil Society Against Violent Extremism (C-SAVE) Testimonies of former child soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo “This is my story”: Children’s war memoirs and challenging protectionist discourses Helen Berents Living through war: Mental health of children and youth in conflict-affected areas Rochelle L. Frounfelker, Naris Islam, Joseph Falcone, Jordan Farrar, Chekufa Ra, Cara M. Antonaccio, Ngozi Enelamah and Theresa S. Betancourt Born in the twilight zone: Birth registration in insurgent areas Kathryn Hampton The Policy on Children of the ICC Office of the Prosecutor: Toward greater accountability for crimes against and affecting children Diane Marie Amann International humanitarian law, Islamic law and the protection of children in armed conflict Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action Ahmed Al-Dawoody and Vanessa Murphy Child marriage in armed conflict Dyan Mazurana, Anastasia Marshak and Kinsey Spears Engaging armed non-State actors on the prohibition of recruiting and using children in hostilitites: Some reflections from Geneva Call’s experience Pascal Bongard and Ezequiel Heffes Taking measures without taking measurements? An insider’s reflections on monitoring the implementation of the African Children’s Charter in -

Gallery Frames

Collectors make a difference The South Dakota Art Museum has received an extensive, growing donation of valuable fine art prints that offer visitors an encyclopedic collection of printmaking from the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. The collection includes impressive examples of pop, op, abstract, color field and photo-realist art. The donation comes from Neil C. Cockerline, a former preservation services director and senior conservator with the Midwest Art Conservation Center in Minneapolis, MN in memory of his late mother Florence L. Cockerline. From initial appraisals, the value of the collection in today’s art market ranges between $500,000 and $1 million. Neil C. Cockerline holding a print by Robert Indiana called “Jo the Loiterer” The collection currently contains more than 400 prints and will continue to grow with the South Dakota Art Museum as its permanent home. The Cockerline Collection features more than 100 notable artists including Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Motherwell, Andy Warhol, Henri Matisse and Robert Indiana. The works are all original prints which means the artist was present or had strict control of the piece during the printmaking process. After each edition is completed, the plate or screen used to make the print is destroyed, making all the pieces in the collection rare. “I chose to donate this collection to the South Dakota Art Museum because I knew the staff and university are very supportive of the museum, and they have a reputation of professionalism and a commitment to preservation. The collection will also attract people to the museum. There isn’t a collection like this in the state or nearby.” Cockerline selected each piece to be included in the first exhibition. -

Photographer: Myriam Boulous

Photographer: Myriam Boulous Caption: Ahmad takes a break to pray in Mar Mikhael. He is part of a Palestinian association that is helping the victims of the explosion. Artist Bio: Born in Beirut in 1992, Myriam Boulos graduated with a master degree in photography from the Academie Libanaise des Beaux Arts in 2015. She took part in both national and international collective exhibitions, including Photomed, Beirut Art Fair, Berlin PhotoWeek, Mashreq to Maghreb (Dresden, Germany), Beyond boundaries (New York), C’est Beyrouth (Paris) and 3ème biennale des photographes du monde arabe (Paris). She received the Byblos Bank Award for Photography in 2014, which lead to her rst solo exhibition at the Byblos Bank in April 2015. Her second solo exhibition took place at the French institute of Lebanon in 2019. Myriam uses her camera to question the city, its people, and her place among them. Her photo series are a mix of documentary and personal research. Instagram: @myriamboulous Website: www.myriamboulous.com Photographer: Omar Sfeir Caption: As Sfeir photographed Lebanons October Revolution and captured its surreal moments, he was reminded of the work of French surrealist artist, artist Rene Magritte. His work pays homage to Magritte’s painting, “The Lovers,” but with a distinctly Lebanese feel. Artist Bio: Omar Sfeir is a lmmaker and photographer whose work focuses on documenting human intimacy and the complexity of relationships with regards to gender and sexuality. In addition to questioning norms and challenging the role of ruling elites, Sfeir’s work examines societal behaviors on a grand scale through the lens of political movements, uprisings and revolutions. -

CHILD MARRIAGE in HUMANITARIAN SETTINGS Millions of Lives Are Being Torn Apart by Conflict, Disasters and Displacement

Z Thematic brief August 2018 CHILD MARRIAGE IN HUMANITARIAN SETTINGS Millions of lives are being torn apart by conflict, disasters and displacement. Girls are hit particularly hard and face many forms of violence. Child marriage has been rising at an alarming rate in humanitarian settings. This brief summarises what we know about this issue and what needs to be done. Why is this an important issue? cause of child marriage in both stable and crisis contexts, often in times of crisis, families see child • Nine out of the ten countries with the highest child marriage as a way to cope with greater economic marriage rates are considered either fragile or i hardship and to protect girls from increased violence. extremely fragile states. Seven out of the twenty But in reality, it leads to a range of devastating countries with the highest child marriage rates face iv ii consequences. Several organisations have even some of the biggest humanitarian crises. We cannot reported cases of girls turning to suicide as a last ignore child marriage in such settings. v iii resort. • Growing evidence shows that in these settings, child • Yet, child marriage is not being adequately addressed marriage rates increase, with a disproportionate in humanitarian settings. In their evaluation of the impact on girls. While gender inequality is a root Thematic brief emergency response to the Syrian refugee crisis in Child marriage and conflict Turkey, UNHCR highlighted the insufficient attention Conflict devastates millions of lives across the world, to child marriage as a major gap in the United vi forcing families to adopt negative coping mechanisms to Nation’s protection response. -

Gallery Frames

Collectors make a difference The South Dakota Art Museum has received an extensive, growing donation of valuable fine art prints that offer visitors an encyclopedic collection of printmaking from the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. The collection includes impressive examples of pop, op, abstract, color field and photo-realist art. The donation comes from Neil C. Cockerline, a former preservation services director and senior conservator with the Midwest Art Conservation Center in Minneapolis, MN in memory of his late mother Florence L. Cockerline. From initial appraisals, the value of the collection in today’s art market ranges between $500,000 and $1 million. Neil C. Cockerline holding a print by Robert Indiana called “Jo the Loiterer” The collection currently contains more than 400 prints and will continue to grow with the South Dakota Art Museum as its permanent home. The Cockerline Collection features more than 100 notable artists including Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Motherwell, Andy Warhol, Henri Matisse and Robert Indiana. The works are all original prints which means the artist was present or had strict control of the piece during the printmaking process. After each edition is completed, the plate or screen used to make the print is destroyed, making all the pieces in the collection rare. “I chose to donate this collection to the South Dakota Art Museum because I knew the staff and university are very supportive of the museum, and they have a reputation of professionalism and a commitment to preservation. The collection will also attract people to the museum. There isn’t a collection like this in the state or nearby.” Cockerline selected each piece to be included in the first exhibition.