The Sheffield College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20150622 Sheffield UTC

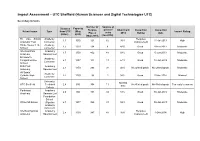

Impact Assessment – UTC Sheffield (Human Sciences and Digital Technologies UTC) Secondary Schools: Number of Surplus at Distance Capacity Surplus point of Attainment Inspection Inspection School name Type from UTC (May Impact Rating Places entry 2014 Rating Date (miles) 2013) (May 2013) (Jan 2014) Fir Vale School Academy Requires 1.1 1050 121 62 36% 11-Jul-2013 High Academy Trust Converter Improvement Hinde House 3-16 Academy 1.5 1320 134 0 42% Good 8-Nov-2012 Moderate School Converter Sheffield Park Academy 1.7 1300 402 41 64% Good 5-Jun-2013 Moderate Academy Sponsor Led Brinsworth Academy Comprehensive 2.1 1487 144 13 64% Good 14-Jun-2012 Moderate Converter School Firth Park Academy 2.1 1350 298 38 40% No Ofsted grade No Ofsted grade Moderate Academy Sponsor Led All Saints' Academy Catholic High 2.2 1290 -96 -1 54% Good 7-Mar-2014 Minimal Converter School University No KS4 UTC Sheffield Technical 2.4 600 394 11 No Ofsted grade No Ofsted grade Too early to assess data College Parkwood Academy 2.6 900 151 34 51% Good 30-Jan-2014 Moderate Academy Sponsor Led Foundation School Winterhill School (Pipeline 2.7 1577 365 83 59% Good 30-Jan-2013 Moderate academy converter) Sheffield Springs Academy Requires 2.8 1300 347 43 36% 1-Oct-2014 High Academy Sponsor Led Improvement Community Handsworth School Grange (Pipeline 3.0 1025 17 4 58% Good 24-May-2012 Minimal Community academy Sports College converter) Outwood Academy 3.1 1200 245 47 54% No Ofsted grade No Ofsted grade Moderate Academy City Sponsor Led Academy Requires Chaucer School 3.2 900 92 28 29% 25-Jun-2014 High Sponsor Led Improvement King Edward VII Community Requires 3.2 1649 -96 -3 62% 19-Apr-2013 Minimal School School Improvement Yewlands Academy Technology 3.6 900 48 21 49% Inadequate 12-Mar-2014 Moderate Converter College Summary Within the local area of the proposed UTC, it is expected that only three schools may feel a high impact, eight may feel a moderate impact and three schools may feel a minimal impact. -

Monthly Trade & Industry Focus July 2014 Business MONTHLY How Sweet

The Star’s monthly trade & industry focus July 2014 Business MONTHLY How sweet... a Franco becomes crafty new way the Big Mac at to network PAGE 26 McDonald’s PAGE 3 Agriculture is a case of like father, FARMING STAYS like son: FAMILY MATTER PAGE 5 Lawyer shows her True Colours in our Smarten Up The Boss makeover: Page 23 2 THE STAR www.thestar.co.uk Wednesday, July 2, 2014 BUSINESS SHOWCASING BUSINESSES n innovative fit- Départ International Busi- Leaders of over 30 leading to track performance and Jo Davison – EDITOR ness system that ness Festival in Sheffield. businesses will be showcas- recovery. aspires to help Sport Tech Match is part ing their skills and services. Details of free workshops, win the global of a packed programme of MIE Medical Research seminars and conferences race is among the activity at the English In- Limited will be demonstrat- are at www.letour.york- technology being stitute of Sport from today ing FitQuest, an innovative shire.com/cycling-culture- Ashowcased at the Grand until Friday. instrument that can be used and-business. Le Tour - think of it as a giant selfie ’ll be honest. Since in the world swooping to- ditching my broth- wardS Attercliffe. er’S fake Raleigh The Tour de France is Chopper in a hedge on our patch. Not that because my Free- you’d know it. I went down Time to switch man’s flares kept Winco’s Newman Road and Igettingca ught in the chain, up the soon-to-be-legen- I haven’t cycled much. -

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

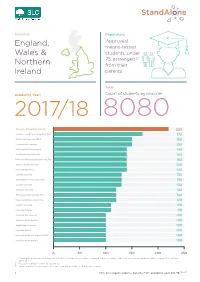

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Sheffield City Region Area Review Final Report

Sheffield City Region Area Review Final report November 2016 Contents Background 4 The needs of the Sheffield City Region 6 Demographics and the economy 6 Patterns of employment and future growth 10 LEP priorities 10 Feedback from LEPs, employers, local authorities and students 11 The quantity and quality of current provision 13 Performance of schools at Key Stage 4 14 Schools with sixth-forms 14 The further education and sixth-form colleges 15 The current offer in the colleges 16 Quality of provision and financial sustainability of colleges 18 Higher education in further education 19 Provision for students with special educational needs and disability (SEND) and high needs 19 Apprenticeships and apprenticeship providers 20 Competition 21 The need for change 22 The key areas for change 22 Initial options raised during visits to colleges 22 Criteria for evaluating options and use of sector benchmarks 24 Assessment criteria 24 FE sector benchmarks 24 Recommendations agreed by the steering group 25 Dearne Valley College and the RNN Group 26 Barnsley College and Doncaster College 26 Sheffield College 26 Thomas Rotherham College and Longley Park Sixth Form 27 Delivery and growth of apprenticeships 27 Implementation group 27 2 Curriculum mapping 27 Support to governing bodies 28 Conclusions from this review 29 Next steps 31 3 Background In July 2015, the government announced a rolling programme of around 40 local area reviews, to be completed by March 2017, covering all general further education and sixth-form colleges in England. The reviews are designed to ensure that colleges are financially stable into the longer-term, that they are run efficiently, and are well-positioned to meet the present and future needs of individual students and the demands of employers. -

Yorkshire & Humberside Service Report September

Yorkshire & Humberside Service Report September 2019 1 Yorkshire & Humberside Service Report September 2019 Service Availability The SLA target sets a minimum of 99.7% availability for each customer, averaged over a 12 month rolling period Periods of scheduled and emergency maintenance are discounted when calculating availability of services Monthly and annual availabilities falling below 99.7% are highlighted * Service has resilience - where an organisation retains connectivity during an outage period by means of a second connection, the outage is not counted against its availability figures 12 Month Service Oct 18 Nov 18 Dec 18 Jan 19 Feb 19 Mar 19 Apr 19 May 19 Jun 19 Jul 19 Aug 19 Sep 19 Rolling Availability Askham Bryan College, York Campus 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Barnsley College 100% 100% 99.94% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% >99.99% Barnsley College, Honeywell Lane 0.00% 0.00% 0.00% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% <12 Months Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council, Personal & 100% 100% 99.94% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% >99.99% Community Development Bishop Burton College, Bishop Burton 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Bradford College 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Bradford College, The David Hockney Building 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Calderdale College 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Calderdale Metropolitan Borough -

Sheffield's Language Education Policies

Rev 28.11.08 Council of Europe CITY REPORT Sheffield’s Language Education Policies Cllr M. Reynolds January 2008 Final pre visit report 28.11.08 Council of Europe City Report: Sheffield’s Language Education Policies CONTENTS Section 1 Factual Description of Sheffield Page 1.1 Sheffield- general overview 6 1.2 Sheffield’s economy 8 1.3 Sheffield – ethnic composition and diversity 10 1.4 Sheffield – political and socio-economic structures 13 1.4.1 Political structures and composition 13 1.4.2 Social division 15 1.4.3 ‘Sheffield First’ 17 1.4.4 ‘Creative Sheffield’ 17 1.4.5 Sheffield Chamber of Commerce and Industry 18 1.5 Sheffield – home languages spoken by children 19 1.6 Policies and responsibilities for Language Teaching 21 1.6.1 Preface 21 1.6.2 Responsibilities for education 21 1.6.3 The education system in England 22 1.6.4 Types of school in England 23 1.6.4.1 Maintained 23 1.6.4.2 Other types of school 25 1.6.5 Current curriculum debates 26 1.6.6 Language education policy: the National Languages Strategy (2002) 27 1.6.7 Policy implementation 28 1.6.8 Higher education networks 29 1.6.9 Innovations in approaches to language education 30 1.7 Education in Sheffield 32 1.7.1 Children and Young People’s Directorate 32 1.7.2 Sheffield’s schools 34 1.7.3 ‘Transforming Learning Strategy’ 35 1.8 Teachers 36 1.8.1 Teacher training structures 36 1.8.2 Methodological approaches to language teaching 37 1.8.2.1 Primary 37 1.8.2.2 Secondary (Key Stage 3) 38 1.8.2.3 Secondary (Key Stage 4) 40 1.8.2.4 Beyond 16 40 2 Final pre visit report 28.11.08 -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

Edtech 50 Yearbook

Magazine Yearbook 2020 The people, products and projects shaping education technology across the UK Edtech 50 2020 Contents PortsmouthPortsmouth College College put put the the iPad iPad at at the the heartheart of of their their teaching teaching and and learning learning strategy strategy 4 Our Developing EdTech Nations InIn March March 2013, 2013, Portsmouth Portsmouth College College received received WhatWhat were were the the best best moments moments of of the the 7 Looking Back a aGood Good Ofsted Ofsted report, report, but but they they didn’t didn’t want want to to iPadiPad project? project? to Look Forward sitsit back back on on that. that. They They knew knew that that they they would would The Edtech 50 needneed to to be be innovative innovative if ifthey they were were to to move move PrincipalPrincipal of of Portsmouth Portsmouth College, College, Simon Simon 10 Edtech 50: People fromfrom Good Good to to Outstanding. Outstanding. They They felt felt that that their their BarrableBarrable said, said, “In “In November November 2017, 2017, we we Yearbook 2020 studentsstudents needed needed to to be be working working harder, harder, and and werewere awarded awarded the the Association Association Of Of Colleges Colleges becomebecome more more independent. independent. They They also also felt felt that that awardaward for for effective effective use use of of technology technology in in 14 Edtech 50: Products Welcome to the Education Foundation’s Edtech it itwas was important important to to improve improve the the digital digital literacy literacy FurtherFurther Education Education (FE). (FE). This This was was something something 50 that celebrates the people, products and ofof their their students students and and prepare prepare them them for for the the thatthat we we were were all all very very proud proud of of and and it itwas was 20 Edtech 50: Projects projects that are shaping education technology modernmodern workplace. -

College and 6 Form Open Events Autumn–Winter 2020-21

College and 6th Form Open Events Autumn–Winter 2020-21 Important! For public safety reasons many of these events will be virtual and / or will need to be pre- booked. Information may also change suddenly. Visit school and college websites to confirm details, times, type of event and whether registration is needed. Do not go without checking first. All Saints 6th Form: www.allsaints.sheffield.sch.uk Sat 7th November Birkdale 6th Form (independent): www.birkdaleschool.org.uk Virtual events plus pre-booked visits Chapeltown Academy: www.chapeltownacademy.com Virtual event - see website Forge Valley 6th Form: https://forgevalley.school Weds 11th November High Storrs 6th Form: https://highstorrs.co.uk Weds 4th November - virtual King Ecgbert 6th Form: www.ecgbert.sheffield.sch.uk Thurs 19th November - virtual King Edward VII 6th Form: www.kes.sheffield.sch.uk Thurs 12th November – virtual Longley Park 6th Form: www.longleypark.ac.uk Sat 17th October Meadowhead 6th Form: www.meadowhead.sheffield.sch.uk Thurs 12th November Notre Dame 6th Form: www.notredame-high.co.uk Sat 14th November Sheffield Girls’ 6th Form (independent): Sat 7th November – virtual www.sheffieldhighschool.org.uk Sheffield South East 6th Form: www.sheffieldpark- Visit website for details academy.org/sixthform Silverdale 6th Form: www.silverdale-chorustrust.org Thurs 22nd October – virtual Tapton 6th Form: www.taptonschool.co.uk Tues 24th November - virtual The Sheffield College Weds 21st October - virtual (City, Hillsborough, Olive Grove and Peaks): Thurs 19th November - virtual -

Police ESOL at Sheffield-College

Third World boost Genetic link David Blunkett MP from Hillsborough World class Dining between bananas Launches CoVE 3 Students 2 returns to Sheffield 3 and humans 10 re:vival fashion show 06 Carrier bags, old tin cans, yoghurt pots and magazines - just a load of rubbish? Not any more! Fashion students from Hillsborough College transformed these familiar items usually found in our bins into exciting and breathtaking garments. Veolia Environmental Services staged a spectacular fashion show at Sheffield City Hall for some of the 2500 members of its Recycling Champions Club. The event was aimed at encouraging more recycling in the city and provided an opportunity to work with the local community through Hillsborough College. Twenty HND Fashion Design students took part in the event. Their brief was to select a favourite designer who inspired them and create an environmentally friendly garment by using only recycled materials. The students spent many weeks researching their project as well as experimenting with various materials before making their final choice. In addition, there was an exhibition of the student's work throughout the year, which gave guests the opportunity to see some stunning garments, one of which had been selected by Clothes Show Live for its show in Birmingham. Sheila Smith, tutor on the HND Fashion Design course, said: "This has been a wonderful experience for our students who have thoroughly enjoyed the whole project. To have the opportunity to showcase their work in a professional fashion show is what every student dreams of. We are very grateful to Veolia Environmental Services for their support." Continued on back page. -

This Is a List of the Formal Names of The

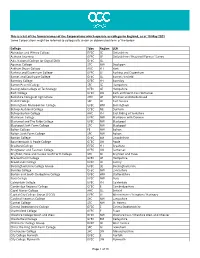

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 10 May 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St. -

PROGRAMME 22Nd - 26Th July 2019 Welcome to the Daily Schedule Invictus UK Trials

PRESENTED BY FUNDED BY PROGRAMME 22nd - 26th July 2019 Welcome to the Daily Schedule Invictus UK Trials Welcome to the Invictus UK Trials Sheffield 2019! We are delighted that you 10:00 - 16:00 Registration are joining us to experience an amazing display of courage and determination, whether as a competitor, family member, friend, carer or proud supporter. English Institute of Sport Sheffield All Competitors and Friends & Family to register at the EISS in Netball For each of the 350+ wounded, injured or sick Veterans and military personnel Court 3 competing, the Trials represent a stage of their recovery journey for them and their families. It is not simply about being the fastest or the strongest. It is about 10:00 - 18:00 Photographic exhibition the recovery benefit and the will to succeed in whatever that individual defines as Sheffield City Hall - Rupert Frere / Wendy Faux success. Winter Garden - Amanda Searle For many, simply leaving their house is a massive achievement, and taking part in Come and see the images of photographers whose work focuses on the sport is just a small element of a wider set of goals. different perspectives of conflict and conflict resolution. Photographers In previous years, the Trials have spanned three days in one venue. This year, in 22nd July Monday Amanda Searle, Rupert Frere and Wendy Faux will be exhibiting. recognition of the growing benefits of being part of Team UK, the Trials have been This event is free to attend and open to all scaled up. With the very generous support of Sheffield City Council, nine sports will take place across multiple venues.