Cross-Examining the Mistaken Witness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proffer, Plea and Cooperation Agreements in the Second Circuit

G THE B IN EN V C R H E S A N 8 D 8 B 8 A E 1 R SINC Web address: http://www.law.com/ny VOLUME 230—NO.27 THURSDAY, AUGUST 7, 2003 OUTSIDE COUNSEL BY ALAN VINEGRAD Proffer, Plea and Cooperation Agreements in the Second Circuit he Department of Justice over- Northern and Western districts provide sees 93 U.S. Attorney’s offices that proffer statements will not be used in throughout the country and any criminal proceeding, the Eastern and beyond. Thousands of criminal Southern agreements are narrower, T promising only that such statements will prosecutors in these offices are responsible for enforcing a uniform set of criminal not be introduced in the government’s statutes, sentencing guidelines and case-in-chief or at sentencing. Thus, Department of Justice internal policies. proffer statements in those districts may Among the basic documents that are be offered at detention hearings and criminal prosecutors’ tools of the trade are suppression hearings as well as grand proffer, plea and cooperation agreements. jury proceedings. These documents govern the relationship Death Penalty Proffer. The Eastern between law enforcement and many of the District’s proffer agreement has a provision subjects, targets and defendants whom defendant) to make statements to the that assures a witness or defendant that DOJ investigates and prosecutes. government without fear that those proffer statements will not be considered Any belief that these agreements are as statements will be used directly against the by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in deciding uniform as the laws and policies underly- witness in a later prosecution. -

Proffer Agreements

BAR OURNAL J FEATURE States Attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York provides: [T]he Office may use any statements made by Proffer Agreements Client: (A) to obtain leads to other evidence, which evidence may be used by the Office in any stage of a criminal prosecution (including What Is Your Client Waiving but not limited to detention hearing, trial or sentencing), civil or administrative proceeding, (B) as substantive evidence to and Is It Worth the Risk? cross-examine Client, should Client testify, and (C) as substantive evidence to rebut, directly or indirectly, any evidence offered or elicited, BY JOHN MCCAFFREY & JON OEBKER or factual assertions made, by or on behalf of Client at any stage of a criminal prosecution (including but not limited to detention hearing, our client is the target of a federal a plea of guilty later withdrawn” is inadmissible trial or sentencing).(Emphasis added.) investigation. He is offered the against the defendant. It is well-settled that the In practice, the particular language of these opportunity to speak with prosecutors protections afforded under these rules can be agreements determines what triggering events Yand investigators so that they have “his side” waived in proffer agreements, thus opening the open the door to the admission of a client’s of the story before determining whether door for a client’s statements to be used against proffer statements at trial. For example, in charges will be pursued. You may ask yourself, him at trial. United States v. Mezzanatto, 513 United States v. Gonzalez, 309 F.3d 882 (5th “What do I have to lose?” Well, the answer is U.S. -

The Child Witness in Tort Cases: the Trials and Tribulations of R

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 24 | Issue 1 Article 2 1998 The hiC ld Witness in Tort Cases: The rT ials and Tribulations of Representing Children Chris A. Messerly Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Messerly, Chris A. (1998) "The hiC ld Witness in Tort Cases: The rT ials and Tribulations of Representing Children," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 24: Iss. 1, Article 2. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol24/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Messerly: The Child Witness in Tort Cases: The Trials and Tribulations of R THE CHILD WITNESS IN TORT CASES: THE TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS OF REPRESENTING CHILDREN Chris A. Messerlyt Trib-u-la-tion; n: distress or suffering resulting from op- pression, persecution or affliction also: a trying experi- ence.* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................169 II. To TESTIFY OR NOT TO TESTIFY, THAT IS THE QUESTION ....170 A . Obeying the Child ..............................................................171 III. IS THE CHILD COMPETENT TO TESTIFY? ................................178 IV. PREPARING THE CHILD TO MEET DARTH VADER ...................180 V. PRESENTING THE CHILD'S "TESTIMONY" WITHOUT CALLING THE CHILD TO TESTIFY ...........................................184 VI. CONCLUSION ..........................................................................188 I. INTRODUCTION A child's testimony may provide some therapeutic value for the child,1 but, at the same time it is unquestionably traumatic for a child. -

Why Prosecutors Are Permitted to Offer Witness Inducements: a Matter of Constitutional Authority*

WHY PROSECUTORS ARE PERMITTED TO OFFER WITNESS INDUCEMENTS: A MATTER OF CONSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY* Hon. H. Lloyd King, Jr.** INTRODUCTION Prosecutors1 in the twenty-first century will undoubtedly face ever more resourceful criminals who will devise increasingly sophis- ticated and complex methods of operation designed to shield their activities and identities from detection by law enforcement.2 As now, next century's prosecutors will find accomplice testimony to be an essential tool in piercing the veil of secrecy surrounding the leaders of organized crime and narcotics trafficking, as well as detecting cor- ruption by public officials and white-collar criminals.3 Obviously, * © H. Lloyd King, Jr., 1999. All rights reserved. ** Immigration Judge, Miami, Florida. B.A., Henderson State University, 1975; J.D., University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1978. Immigration Judges are appointed by, and serve under the direction of, the Attorney General of the United States. The views expressed in this Article are those of the Author and are not necessarily the views of the United States Department of Justice. Prior to appointment as an Immigration Judge, the Author served as an Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, and as Chief Deputy Prosecuting Attorney and Deputy Prosecuting Attorney for the Sixth Judicial District of Arkansas. 1. This Article primarily examines the federal prosecutor's role in offering induce- ments to government witnesses. The issues addressed in this Article are, however, equally relevant to state prosecutors in light of similar challenges to witness inducement agreements raised in various state jurisdictions. See, e.g., Neil B. Eisenstadt, Let's Make a Deal: A Look at United States v. -

The Perils of Calling Your Opponent As a Witness in Your Case

OUTSIDE PERSPECTIVES The Perils Of Calling Your Opponent As A Witness In Your Case YEARS AGO, I WATCHED A PLAINTIFF’S ing on direct did not voluntarily take the stand and, attorney fail miserably in his attempts to tell his more importantly, did not have the opportunity prior to client’s story to a jury through his very first wit- examination by the opposing counsel to fully tell his or ness – one of the named her story. Many judges under these circumstances will Michael A. Stick defendants. At a recess, a allow an adverse witness greater freedom to deviate friend said to me: “This from the standard “yes or no” answers of cross exami- just proves that you are a nation and to explain their answers. This results in fool if you try to put on your case in chief through a direct examination that is often lengthier, choppier, an adverse witness.” As self-evident as my friend’s less predictable, and ultimately less compelling than a advice might seem, it is often ignored. tight, clean cross examination of the same witness in Except under unique circumstances, examining an your opponent’s case. The time to examine an unpre- adverse witness on direct during your case in chief dictable and hostile witness is during cross examina- for any extended period of time is usually a mistake. tion and not on direct during your case in chief. To begin with, using an adverse witness as your To make matters worse, juries in particular might spokesperson is simply not a compelling way to offer sympathize more with an adverse witness being exam- your evidence at trial. -

Judicial Gatekeeping of Police-Generated Witness Testimony Sandra Guerra Thompson

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 102 | Issue 2 Article 2 Spring 2012 Judicial Gatekeeping of Police-Generated Witness Testimony Sandra Guerra Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Sandra Guerra Thompson, Judicial Gatekeeping of Police-Generated Witness Testimony, 102 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 329 (2013). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol102/iss2/2 This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/12/10202-0329 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 102, No. 2 Copyright © 2012 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. JUDICIAL GATEKEEPING OF POLICE- GENERATED WITNESS TESTIMONY SANDRA GUERRA THOMPSON* This Article urges a fundamental change in the administration of criminal justice. The Article focuses on what I call “police-generated witness testimony,” by which I mean confessions, police informants, and eyewitness identifications. These types of testimony are leading causes of wrongful convictions. The Article shows that heavy-handed tactics by the police have a tendency to produce false evidence of these types, especially when the individuals being questioned by police are particularly vulnerable, such as juveniles or those who are intellectually disabled or mentally ill. It also demonstrates that there are procedural best practices that the police can follow to reduce the dangers of false evidence. -

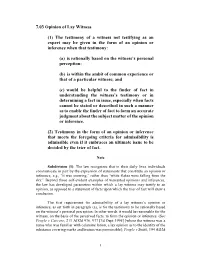

7.03 Opinion of Lay Witness (1) the Testimony of a Witness Not Testifying

7.03 Opinion of Lay Witness (1) The testimony of a witness not testifying as an expert may be given in the form of an opinion or inference when that testimony: (a) is rationally based on the witness’s personal perception; (b) is within the ambit of common experience or that of a particular witness; and (c) would be helpful to the finder of fact in understanding the witness’s testimony or in determining a fact in issue, especially when facts cannot be stated or described in such a manner as to enable the finder of fact to form an accurate judgment about the subject matter of the opinion or inference. (2) Testimony in the form of an opinion or inference that meets the foregoing criteria for admissibility is admissible even if it embraces an ultimate issue to be decided by the trier of fact. Note Subdivision (1). The law recognizes that in their daily lives individuals communicate in part by the expression of statements that constitute an opinion or inference; e.g., “it was snowing,” rather than “white flakes were falling from the sky.” Beyond those self-evident examples of warranted opinions and inferences, the law has developed parameters within which a lay witness may testify to an opinion, as opposed to a statement of facts upon which the trier of fact will draw a conclusion. The first requirement for admissibility of a lay witness’s opinion or inference, as set forth in paragraph (a), is for the testimony to be rationally based on the witness’s personal perception. -

CHARACTER EVIDENCE QUICK REFERENCE Reputation – Opinion – Specific Instances of Conduct - Habit

CHARACTER EVIDENCE QUICK REFERENCE reputation – opinion – specific instances of conduct - habit Character of the Defendant – 404(a)(1) (pages 14-29) (pages 4-8) * Test: Proper Purpose + Relevance + Time * Test: Relevance (to the crime charged) + Similarity + 403 balancing; rule of inclusion + 403 balancing; rule of exclusion * Put basis for ruling in record (including * Defendant gets to go first w/ "good 403 balancing analysis) character" evidence – reputation or opinion only (see rule 405) * D has burden to keep 404(b) evidence out ^ State can cross-examine as to specific instances of bad character * proper purposes: motive, opportunity, knowledge/intent, preparation/m.o., common * Law-abidingness ALWAYS relevant scheme/plan, identity, absence of mistake/ accident/entrapment, res gestae (anything * General good character not relevant but propensity) * Defendant's character is substantive ^ Credibility is never proper – 608(b), not 404(b) evidence of innocence – entitled to instruction if requested * time: remoteness is less significant when used to show intent, motive, m.o., * D's evidence of self-defense does not knowledge, or lack of mistake/accident - automatically put character at issue * remoteness more significant when common scheme or plan (seven year rule) ^ unless continuous course of conduct, or D is gone * similarity: particularized, but not Character of the victim – 404(a)(2) (pages 8-11) necessarily bizarre ^ the more similar acts are, the less problematic time is * Test: Relevance (to the crime charged) + 403 balancing; -

Second Circuit Clarifies Scope of Proffer Agreement Waivers

G THE B IN EN V C R H E S A N 8 8 D 8 B 1 AR SINCE WWW. NYLJ.COM VOLUME 256—NO. 103 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 29, 2016 Outside Counsel Expert Analysis Second Circuit Clarifies Scope Of Proffer Agreement Waivers lthough securing a coopera- both to white-collar criminal defense tion agreement after proffer- practitioners and to those who prac- ing to the government can tice in the gang-related context in which lead to enormous benefits for Rosemond arose. those who successfully navi- By And Proffer Agreements Agate the process, the negative conse- Harry Helen P. quences of a failed proffer are profound. Sandick O’Reilly The standard proffer agreements in Assessing the risks of whether to proffer the Southern and Eastern Districts of and enter into a proffer agreement is an Mezzanatto, 513 U.S. 196 (1995) that New York typically protect the defen- important part of federal criminal prac- the protections afforded under Rule dant from the government’s use of tice. These written agreements between 410 can be waived in proffer agree- factual assertions made during plea federal prosecutors and a subject of a ments, thereby opening the door for agreements. This is necessary because criminal investigation set the ground the factual assertions made in the proffer rules for the future use by the govern- are inevitably inculpatory: The point of ment of a defendant’s statements made The Second Circuit clarified a proffer is for a defendant to admit his during a proffer session. how and when certain defense participation in the crime and to explain The agreements typically involve a tactics at trial can open the who else was involved in committing the partial waiver of the protections pro- door to the introduction of the crime. -

Legal Professional Privilege

FOI Guide No. 1 Issued: October 2001 Legal Professional Privilege This is a plain English guide to the application of the exemption in clause 7 of the FOI Act. An agency can refuse access to exempt matter or an exempt document. The word “matter” refers to a piece of information. It can be a whole page or part of a page, or a single word or figure on a page. Parts of a page can be exempt when other parts are not. Exemptions are not mandatory; agencies have discretion to disclose documents that may be technically exempt where that may properly be done. Legal professional privilege is a rule of law that protects What is legal the confidentiality of communications made between a professional lawyer and his or her client. The privilege belongs to privilege the client and may only be waived by the client. The exemption in clause 7 protects information that would Purpose be privileged from production in legal proceedings on the ground of legal professional privilege. Criteria Legal professional privilege protects confidential communications between a lawyer and his or her client made for the dominant purpose of - ! seeking or giving legal advice or professional legal assistance; or !use, or obtaining material for use, in legal proceedings that had commenced, or were reasonably anticipated, at the time of the relevant communication. Other Legal professional privilege also protects confidential communications communications between the client or the client’s that are also lawyers (including communications through employees or protected agents) and third parties made for the dominant purpose of use, or obtaining material for use, in legal proceedings that had commenced, or were reasonably anticipated, at the time of the relevant communication. -

3. Form of Witness Examination

3. FORM OF WITNESS EXAMINATION 1. Judicial Discretion The trial judge has broad discretion to control the procedure of interrogating witnesses and presenting evidence so that the trial furthers three goals: facilitating truth-determination, avoiding waste of time, and protecting witnesses from harassment. 2. Separation of Witnesses At the request of a party, the judge must order witnesses excluded from the courtroom so they cannot hear the testimony of others and (purposely or inadvertently) alter their own testimony to be consistent. Rule 615. The order should include a prohibition against discussing testimony outside the courtroom. The rule does not apply to parties, who may remain in the courtroom. If a party is an organization, it may designate one representative to remain in the courtroom to assist the attorney. In criminal cases, this is usually the lead detective. The judge has discretion to also allow an expert witness to remain in the courtroom and assist counsel in a complex cross-examination of the opposing expert. The victim of a crime may not be designated by the State to remain in the courtroom, but may be called as the first witness and then allowed to remain after testifying. 3. Basic Procedure The basic principle of witness testimony is that it must be presented in question-and-answer format, i.e: a. The attorney asks questions. b. The witness supplies answers. This means three things: a. The attorney must ask a question and not make statements and arguments. If the attorney makes a remark, such as "That's very odd, considering it was pitch dark outside," you may object that "This is a statement, not a question." b. -

Military Rules of Evidence

PART III MILITARY RULES OF EVIDENCE SECTION I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101. Scope the error materially prejudices a substantial right of (a) Scope. These rules apply to courts-martial the party and: proceedings to the extent and with the exceptions (1) if the ruling admits evidence, a party, on the stated in Mil. R. Evid. 1101. record: (b) Sources of Law. In the absence of guidance in (A) timely objects or moves to strike; and this Manual or these rules, courts-martial will apply: (B) states the specific ground, unless it was (1) First, the Federal Rules of Evidence and the apparent from the context; or case law interpreting them; and (2) if the ruling excludes evidence, a party in- (2) Second, when not inconsistent with subdivi- forms the military judge of its substance by an offer of proof, unless the substance was apparent from the sion (b)(1), the rules of evidence at common law. context. (c) Rule of Construction. Except as otherwise pro- (b) Not Needing to Renew an Objection or Offer of vided in these rules, the term “military judge” in- Proof. Once the military judge rules definitively on cludes the president of a special court-martial the record admitting or excluding evidence, either without a military judge and a summary court-mar- before or at trial, a party need not renew an objec- tial officer. tion or offer of proof to preserve a claim of error for appeal. Discussion (c) Review of Constitutional Error. The standard Discussion was added to these Rules in 2013. The Discussion provided in subdivision (a)(2) does not apply to er- itself does not have the force of law, even though it may describe rors implicating the United States Constitution as it legal requirements derived from other sources.