Prejudice Vs. Probative Value, Philadelphia Style

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Pratt Is One of Hollywood's Most Sought

CHRIS PRATT BIOGRAPHY: Chris Pratt is one of Hollywood’s most sought- after leading men. Pratt will next appear in The Magnificent Seven opposite Denzel Washington and Ethan Hawke for director, Antoine Fuqua on September 23, 2016. Chris just wrapped production on the highly anticipated Sony sci-fi drama, Passengers opposite Jennifer Lawrence for Oscar nominated director of The Imitation Game, Morten Tyldum. The film is slated for a December 2016 release. Most recently, Chris headlined Jurassic World which is the 4th highest grossing film of all time behind Avatar, Titanic, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens. He will reprise his role of 'Owen Grady’ in the 2nd installment of Jurassic World- set for a 2018 debut. 2015 also marked the end of seventh and final season of Emmy- nominated series Parks & Recreation for which Pratt is perhaps best known for portraying the character, ‘Andy Dwyer’ opposite Amy Poehler, Nick Offerman, Aziz Ansari, and Adam Scott. 2014 was truly the year of Chris Pratt. He top lined Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy which was one of the top 3 grossing films of 2014 with over $770 million at the global box office. He will return to the role of ‘Star Lord’ in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 which is scheduled for a May 2017 release. Plus, Chris lent his vocal talents to the lead character, ‘Emmett,’ in the enormously successful Warner Bros, animated feature The Lego Movie which made over $400 million worldwide. Other notable film credits include: the DreamWorks comedy Delivery Man, Spike Jonze’s critically acclaimed, Her, and the Universal comedy feature, The Five-Year Engagement. -

Wickline Casting's Film & TV Program Gwynedd Mercy Academy

Wickline Casting’s Film & TV Program at Gwynedd Mercy Academy First Trimester Thursday’s October 13, 20, November 3, 10, 17 We are thrilled to bring our very unique Film & TV course to your school. Starting in October, Wickline Casting will be “rolling camera” at your school! Your child will learn how to shine in front of the camera or learn how to make it happen “behind the scenes”. We have pulled together a special diversified course to show your child all the basics in Acting for Camera, Directing For Camera, Camera-Operating, and Scriptwriting. Everyone will learn several ways of developing commercials and film scenes from start to finish. Wickline Casting has over 10,000 credits in commercials, Academy Award winning feature films and television. We are best known for our work on “Philadelphia” with Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington, “The Long Kiss Goodnight” with Geena Davis and Samuel L. Jackson. In addition, among our television credits are numerous Cambells, Build-A-Bear, ABC Daytime Soap Operas, NBC-10, Toyota, Hasbro Toys, IKEA, AC Moore and Sesame Place. Aside from Kathy being a successful casting director, her commitment is to share filmmaking with children through after school programs and summer camps throughout PA NJ and DE. Our instructors are professional actors and directors with impressive credits. We are excited about showing young people how to bring the art of on-camera into their lives, whether it is just for fun or career aspirations. You never know…you could have the next Steven Spielberg or Jennifer Lawrence in your household! Please contact us with any questions. -

Demme Takes AIDS and Homophobia to Streets of 'Philadelphia' and Succeeds

Page 10, Sidelines - February 21.1994 Features Demme takes AIDS and homophobia to streets of 'Philadelphia' and succeeds SAM GANNON CONTRIBUTING EDITOR How can any director make a movie on one the hand and Wyant, Wheeler, in America about a touching, yet Hellerman, Tetlow and Brown on the controversial subject without being other. attacked from all sides? "Philadelphia" is Washington angles in on the dark, the first big-budget, big-star film to deal brooding side of mankind. The with the subjects of AIDS, homophobia homophobia he exhibits is not unnatural and discrimination. The industry has been or uncommon today, but he turns over waiting. The AIDS community and not only a new leaf, but his entire life. He activists have been waiting. Most of all, goes from a man resentful and ignorant the public has been waiting. Now that the about AIDS and homosexuals to a man cat is out of the bag, detractors from all who truly cares about Andy, a gay man, groups have slung muddy criticism at the and his life and death. When Beckett producers, director, actors and appears at Miller's doorstep in search of screenwriter. representation, Miller is frantic, watching There will always be criticism: It what is touched and how it is handled. doesn't accomplish enough, it doesn't He immediately visits his doctor for an explore this, there's too much of this and AIDS test. This is homophobia; true fear not enough of that—the complaints go on. fills Washington's Miller. By movie's end, How much can the first industry film do however, he is embracing Andy. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

H 5584 State of Rhode Island

2017 -- H 5584 ======== LC001925 ======== STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2017 ____________ H O U S E R E S O L U T I O N CONGRATULATING VIOLA DAVIS FOR WINNING BEST ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Introduced By: Representatives Mattiello, Shekarchi, Morgan, McLaughlin, and Maldonado Date Introduced: February 28, 2017 Referred To: House read and passed 1 WHEREAS, Award-winning actress and producer Viola Davis was born on August 11, 2 1965, in South Carolina, a daughter of Mary Alice and Dan Davis. Her family moved to Central 3 Falls, Rhode Island, when she was two-months old and despite living in poverty as a child, she 4 excelled at Central Falls High School, where she developed her love and passion for the arts and 5 acting; and 6 WHEREAS, As a teenager, Ms. Davis enrolled in the Young People's School for the 7 Performing Arts in West Warwick, where her immense artistic talents were first discovered. 8 Following graduation from high school, she enrolled at Rhode Island College, majoring in theater 9 and graduating in 1988. After graduating from Rhode Island College, she attended the prestigious 10 Juilliard School and was a member of the school's Drama Group; and 11 WHEREAS, Ms. Davis earned her Screen Actors Guild card in 1996, and proceeded to 12 act in numerous forums, including Broadway, television and motion pictures. In 2001, she won a 13 Tony Award and a Drama Desk Award for her portrayal of a struggling mother in King Hedley II. 14 She won another Drama Desk Award for her performance in the 2004 Off-Broadway Production 15 of Intimate Apparel; and 16 WHEREAS, In 2008, Ms. -

“Fall Forward” – Denzel Washington's Inspiring Commencement Speeches

Speech “Fall Forward” – Denzel Washington’s Inspiring Commencement Speeches Denzel Washington commencement speeches to University of Pennsylvania and Dillard University You’ve invested a lot in your education, and people have invested in you. And let me tell you the world needs your talents, and does it ever? The world needs a lot and we need it from you. We really do. We need it from you, young people. I mean, I’m not speaking for the rest of us up here, but I know I’m getting a little grayer. We need it from you, the young people, because remember this: you’ve got to get out there, and you got to give it everything you got. Whether it's your time, your talent, your prayers, or your treasures. Because remember this: you will never see a u-haul behind a hearse. I’ll say it again: You will never see a u-haul behind a hearse. The Egyptians tried it—and all they got was robbed! So the question is: what are you going to do with what you have? And I’m not talking about how much you have. Some of you are business majors. Some of you are theologians, nurses, sociologists. Some of you have money. Some of you have patience. Some have kindness. Some have love. Some of you have the gift of long-suffering. Whatever it is… whatever your gift is, what are you going to do with what you have? Fail big. That’s right. Fail big. Today is the beginning of the rest of your life and it can be very frightening. -

Denzel Washington and the Equalizer Celebrity Brand Assessment and Market Positioning Topline

Click to edit Master text styles Denzel Washington and The Equalizer Celebrity Brand Assessment and Market Positioning Topline Methodology & Key Findings METHODOLOGY ► PENN SCHOEN BERLAND conducted a Denzel Washington Brand Study and Equalizer franchise and positioning study to evaluate Denzel Washington’s and The Equalizer’s health and essence, and potential interest in The Equalizer movie adaptation starring Washington. The online study was conducted among 1000 moviegoers 17-54 including: 300 African Americans, 275 Equalizer Viewers and 550 Denzel Washington Fans. TOPLINE FINDINGS ► DENZEL IS TOP TIER: Denzel Washington is among the top of his class – he has extremely strong fanship, (50% of moviegoers say they are ‘big fans’ - only below Morgan Freeman and Tom Hanks), 7 in 10 say he is ‘on the way up’ (among the top third of all actors tested), and he drives the highest interest in seeing a new movie with a stellar 44% of moviegoers saying they are ‘definitely interested’ in seeing the next film he stars in. ► FANSHIP SKEWS AA & OVER 35 : Denzel Washington's fans skew AA (23% of his fanbase vs.15% overall) and Older (58% of his fanbase are over 35 vs. 50% overall). Additionally, while both Older Males and Older Females are similarly strong supporters, there is a gender split among Younger moviegoers with Younger Females much less enthusiastic than Younger males (36% ‘big fans’ for Younger Females vs. 48% for Younger Males). ► MOVIEGOERS WANT DENZEL TO BE THE CONFIDENT PROTECTOR: Moviegoers want to see Denzel as tough, confident, and intense and at the same time likable and heroic. -

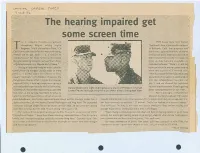

The Hearing Impaired Get Some Screen Time

LI\N:, I� CAP(fc\L T'IM(.) CJ -2.2,,.crc.. The hearing impaired get some screen time ry to imagine Casablanca without SHH books films from Tripod Humphrey Bogart telling Ingrid Captioned Films, a non-profit company T Bergman, uwe'II always have Paris." Or in Burbank, Calif. that prepares and CoolHand Luke without Strother Martin declaring, distributes captioned editions of recent "What we've got here ... is a failure to films to non-profit organizations such as communicate." Or Pulp Fiction without John SHH. Coscarelli books the most popular Travolta informing Samuel L. Jackson that in Paris, films as they become available in a Quarter-Pounder is a "Royale With Cheese." captioned editions. "There's a time lag Having a hard time? Imagine what a deaf or between when the movie comes out and hard-of-hearing filmgoer would make of these when they caption it," Coscarelli said. films - or for that matter most American films, "They have to get the fi Im fromthe studio usually top-heavy with dialogue. However, the and send it off to caption it, and that takes Capitol Area chapter of Self-Help forthe Hearing time. But Independence Day came out Impaired (SHH), is helping to make moviegoing a July 3, and we showed the captioned more enjoyable experience for the hard of hearing. version later that month. They're getting Denzel Washington (right) interrogates Lou Diamond Phillips in Courage Since March, they've beensponsoring a captioned Under Fire, the next captioned film to be shown at the LansingMall West better about getting movies out faster." film series at the Lansing Mall West Cinema, in Not surprisingly, Independence which recent Hollywoodhits are shown in special Day and Toy Story have been SHH's most subtitled editions. -

Denzel Washington: America's Favorite Movie Star

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Denzel Washington: America’s Favorite Movie Star After two years at #1, Tom Hanks drops to #2, according to a new Harris Poll ROCHESTER, N.Y. – January 16, 2007 – Hollywood movie star Denzel Washington returns to the list of America’s favorite movie stars in dramatic fashion, taking the number one position after dropping off the top ten list in 2005. Dropping from number one to number two is Tom Hanks, while movie legend John Wayne remains in third place. Tough guy Clint Eastwood jumps up two spots to fourth place. These are the results of a nationwide Harris Poll of 1,147 U.S. adults surveyed online by Harris Interactive ® between December 12 and 18, 2006. Will Smith also joins the list this year, perhaps due to the recent success of his film, The Pursuit of Happyness . Smith not only joins the top ten for the first time, but does so tied for fifth place. While all the other stars are the same, they have changed places within the top ten. Some of these changes include: • Harrison Ford is the biggest mover as he drops seven places from tied for #3 to #10. This excludes him from the top five for the first time since 1997; • Julia Roberts is tied for #5, a spot held alone in 2005. She is still alone in one regard – this Pretty Woman is the only female to appear in the top ten; • Johnny Depp drops five spots on the list. In 2005, he was #2 and this time out he is tied for #7. -

Denzel Washington Remains America's Favorite Movie Star

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Denzel Washington Remains America’s Favorite Movie Star Even Though He Hasn’t Made a Movie since 1976, John Wayne Remains on the List at Number Six ROCHESTER, N.Y. – January 15, 2008 – Whether it was his appearances in American Gangster or The Great Debaters, Denzel Washington scores the top position as America’s favorite movie star for the second year in a row on The Harris Poll’s annual favorite movie star list. In second place, also for the second year in a row, is Charlie Wilson’s War, or rather, Tom Hanks. Perhaps due to the success of the final Pirates of the Caribbean or his singing skills in Sweeney Todd, Johnny Depp moves from a seventh place tie to third place this year. Finishing out the top five are a Pretty Woman, Julia Roberts (#4), and one of the Men in Black, Will Smith (#5), who were each tied for fifth place on last year’s list. These are the results of a nationwide Harris Poll of 1,114 U.S. adults surveyed online by Harris Interactive® between December 4 and 12, 2007. Rounding out the top ten is one old standard and four movie stars who are new to the list this year, three returning after an absence and one on the list for the first time. In sixth place is John Wayne, who is the only movie star to appear on every Harris Poll top ten movie star list since it first began in 1994. And this is after having died in 1979! Tied for seventh on the list are Matt Damon, who’s Bourne Trilogy may have helped him make his first appearance on the list, and an old James Bond, Sean Connery. -

Open Ninth: Conversations Beyond the Courtroom Judges on Film

1 OPEN NINTH: CONVERSATIONS BEYOND THE COURTROOM JUDGES ON FILM: PART 2 EPISODE 36 DECEMBER 5, 2017 HOSTED BY: FREDERICK J. LAUTEN 2 >>Welcome to another episode of “Open Ninth: Conversations Beyond the Courtroom” in the Ninth Judicial Circuit Court of Florida. Now here’s your host, Chief Judge Frederick Lauten. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: Well, welcome. We are live, Facebook live and podcasting Phase 2 or Round 2 of Legal Eagles. So Phase 1 was so popularly received, and we’re back for Round 2 with my colleagues and good friend Judge Letty Marques, Judge Bob Egan, and we’re talking about legal movies. And last time there were so many that we just had to call it quits and pick up for Phase 2, so I appreciate that you came back for Round 2, so I’m glad you’re here. You ready to go? >>JUDGE MARQUES: Sure. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: Okay, here we go. Watch this high tech. Here’s the deal. We need a box of popcorn, but we’re going to name that movie and then talk a little bit about it. So this is the hint: Who can name that movie from this one slide? >>JUDGE MARQUES: From Runaway Jury? >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: Did you see the movie? >>JUDGE EGAN: I did; excellent movie. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: What’s it about? Do you remember? Anybody remember? >>JUDGE MARQUES: He gets in trouble. Dustin Hoffman gets in trouble at the beginning of the movie with the judge, but I don’t remember why. >>CHIEF JUDGE LAUTEN: I don’t know that I’ve seen this movie. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue.