The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Union Is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-1998 In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900 Kathleen C. Haggard Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Haggard, Kathleen C., "In Union is Strength Mormon Women and Cooperation, 1867-1900" (1998). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 738. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/738 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. " IN UNION IS STRENGTH" MORMON WOMEN AND COOPERATION, 1867-1900 by Kathleen C. Haggard A Plan B thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in History UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1998 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Anne Butler, for never giving up on me. She not only encouraged me, but helped me believe that this paper could and would be written. Thanks to all the many librarians and archival assistants who helped me with my research, and to Melissa and Tige, who would not let me quit. I am particularly grateful to my parents, Wayne and Adele Creager, and other family members for their moral and financial support which made it possible for me to complete this program. Finally, I express my love and gratitude to my husband John, and our children, Lindsay and Mark, for standing by me when it meant that I was not around nearly as much as they would have liked, and recognizing that, in the end, the late nights and excessive typing would really be worth it. -

Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J

Mormon Studies Review Volume 4 Number 1 Article 7 1-1-2017 Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, eds., The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women's History Reviewed by Dave Hall, Susanna Morrill, Catherine A. Brekus [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Catherine A. Brekus, Reviewed by Dave Hall, Susanna Morrill, (2017) "Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, eds., The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women's History," Mormon Studies Review: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2/vol4/iss1/7 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mormon Studies Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Catherine A. Brekus: Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matth Review Panel Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, eds. The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History. Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016. Reviewed by Dave Hall, Susanna Morrill, and Catherine A. Brekus DAVE HALL: This work gathers in one useful volume documents piv- otal to understanding the early history of Mormon women. Adding to its value is the wealth of knowledge contributed by its editorial team, headed by experienced scholars Jill Derr, Carol Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew Grow. -

Session Slides

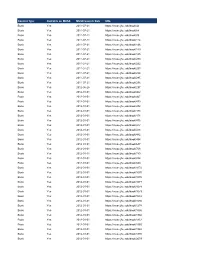

Content Type Available on MUSE MUSE Launch Date URL Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/89 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/114 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/146 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/149 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/185 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/280 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/292 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/293 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/294 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/295 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/296 Book Yes 2012-06-26 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/297 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/462 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/470 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/472 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/473 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/474 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/477 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/478 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/482 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/494 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/687 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/708 Book Yes 2012-01-11 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/780 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/834 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/840 Book Yes 2012-01-01 -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 1 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 1, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS --In Memoriam: Leonard J. Arrington, 5 --Remembering Leonard: Memorial Service, 10 --15 February, 1999 --The Voices of Memory, 33 --Documents and Dusty Tomes: The Adventure of Arrington, Esplin, and Young Ronald K. Esplin, 103 --Mormonism's "Happy Warrior": Appreciating Leonard J. Arrington Ronald W.Walker, 113 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS • --In Search of Ephraim: Traditional Mormon Conceptions of Lineage and Race Armand L. Mauss, 131 TANNER LECTURE • --Extracting Social Scientific Models from Mormon History Rodney Stark, 174 • --Gathering and Election: Israelite Descent and Universalism in Mormon Discourse Arnold H. Green, 195 • --Writing "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview" (1973): Context and Reflections, 1998 Lester Bush, 229 • --"Do Not Lecture the Brethren": Stewart L. Udall's Pro-Civil Rights Stance, 1967 F. Ross Peterson, 272 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss1/ 1 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY SPRING 1999 JOURNAL OF MORMON HISTORY SPRING 1999 Staff of the Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff Editor: Lavina Fielding Anderson Executive Committee: Lavina Fielding Anderson, Will Bagley, William G. -

Jill Mulvay Derr and Karen Lynn Davidson, Eds. Eliza R

Jill Mulvay Derr and Karen Lynn Davidson, eds. Eliza R. Snow: The Complete Poetry. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press; Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2009. Reviewed by Susan Elizabeth Howe t is unfortunate but nevertheless true that most of today’s educated read- Iers do not understand, are indifferent to, or even dislike poetry. Given that fact, many readers might pass up Eliza R. Snow: The Complete Poetry without so much as a glance at its contents. That would be a mistake. In pre- paring this comprehensive collection of Eliza R. Snow’s poetry, editors Jill Mulvay Derr and Karen Lynn Davidson have rightly understood that Eliza’s writings have great significance in their relationship to her personal life as well as the religious and historical events to which she was responding. Derr and Davidson have provided such contextual information by includ- ing in the introduction an overview of Snow’s poetry and a short biography. They also introduce each chapter with more specific historical and personal information about the period in Snow’s life when the chapter’s poems were written. By preceding each of the 507 poems with an explanation of the context and all unfamiliar references, the reader is prepared to encounter and understand Eliza’s verse. Chapter 1 includes Eliza’s earliest work, the poems she wrote between 1825 and 1835. The chapter introduction discusses her parents and grand- parents, the home she grew up in, and her development as a poet. She pub- lished her first poem in the Western Courier newspaper in 1825 when she was twenty-one, after which her poems were regularly featured there and in the Ohio Star (3). -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999

Journal of Mormon History Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 1 1999 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1999) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 25 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol25/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 25, No. 2, 1999 Table of Contents CONTENTS LETTERS viii ARTICLES • --David Eccles: A Man for His Time Leonard J. Arrington, 1 • --Leonard James Arrington (1917-1999): A Bibliography David J. Whittaker, 11 • --"Remember Me in My Affliction": Louisa Beaman Young and Eliza R. Snow Letters, 1849 Todd Compton, 46 • --"Joseph's Measures": The Continuation of Esoterica by Schismatic Members of the Council of Fifty Matthew S. Moore, 70 • -A LDS International Trio, 1974-97 Kahlile Mehr, 101 VISUAL IMAGES • --Setting the Record Straight Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, 121 ENCOUNTER ESSAY • --What Is Patty Sessions to Me? Donna Toland Smart, 132 REVIEW ESSAY • --A Legacy of the Sesquicentennial: A Selection of Twelve Books Craig S. Smith, 152 REVIEWS 164 --Leonard J. Arrington, Adventures of a Church Historian Paul M. Edwards, 166 --Leonard J. Arrington, Madelyn Cannon Stewart Silver: Poet, Teacher, Homemaker Lavina Fielding Anderson, 169 --Terryl L. -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986

Journal of Mormon History Volume 13 Issue 1 Article 1 1986 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 13, 1986 Table of Contents • --Mormon Women, Other Women: Paradoxes and Challenges Anne Firor Scott, 3 • --Strangers in a Strange Land: Heber J. Grant and the Opening of the Japanese Mission Ronald W. Walker, 21 • --Lamanism, Lymanism, and Cornfields Richard E. Bennett, 45 • --Mormon Missionary Wives in Nineteenth Century Polynesia Carol Cornwall Madsen, 61 • --The Federal Bench and Priesthood Authority: The Rise and Fall of John Fitch Kinney's Early Relationship with the Mormons Michael W. Homer, 89 • --The 1903 Dedication of Russia for Missionary Work Kahlile Mehr, 111 • --Between Two Cultures: The Mormon Settlement of Star Valley, Wyoming Dean L.May, 125 Keywords 1986-1987 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol13/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History Editorial Staff LEONARD J. ARRINGTON, Editor LOWELL M. DURHAM, Jr., Assistant Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Assistant Editor FRANK McENTIRE, Assistant Editor MARTHA ELIZABETH BRADLEY, Assistant Editor JILL MULVAY DERR, Assistant Editor Board of Editors MARIO DE PILLIS (1988), University of Massachusetts PAUL M. -

C.001 C., JE “Dr. Duncan and the Book of Mormon.”

C. C.001 C., J. E. “Dr. Duncan and the Book of Mormon.” MS 52 (1 September 1890): 552-56. A defense of the Book of Mormon against the criticism of Dr. Duncan in the Islington Gazette of August 18th. Dr. Duncan, evidently a literary critic, concluded that the Book of Mormon was either a clumsy or barefaced forgery or a pious fraud. The author writes that the Book of Mormon makes clear many doctrines that are difcult to understand in the Bible. Also, the history and gospel taught by the Bible and the Book of Mormon are similar because both were inspired of God. [B. D.] C.002 C., M. J. “Mormonism.” Plainsville Telegraph (March 3, 1831): 4. Tells of the conversion of Sidney Rigdon who read the Book of Mormon and “partly condemned it” but after two days accepted it as truthful. He asked for a sign though he knew it was wrong and saw the devil appearing as an angel of light. The author of this article warns against the Book of Mormon and against the deception of the Mormons. [J.W.M.] C.003 Cadman, Sadie B., and Sara Cadman Vancik. A Concordance of the Book of Mormon. Monongahela, PA: Church of Jesus Christ, 1986. A complete but not exhaustive concordance, listing words alphabetically. Contains also a historical chronology of the events in the Book of Mormon. [D.W.P.] C.004 Caine, Frederick Augustus. Morumon Kei To Wa Nanzo Ya? Tokyo: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1909. A two-page tract. English title is “What is the Book of Mormon?” [D.W.P.] C.005 Cake, Lu B. -

Autobiography in the Poetry of Eliza R. Snow

Inadvertent Disclosure: Autobiography in the Poetry of Eliza R. Snow Maureen Ursenbach Beecher THREE TURNING POINTS MARK THE EARLY LIFE OF ELIZA R. SNOW: the 1826 publication of her first newspaper verse, her 1835 baptism as a convert to Mormonism, and her 1842 sealing as a plural wife of the prophet Joseph Smith. The convergence of these three entities—poetry, religion, and conjugal love—during the turbulent summer and fall of 1842 in Nauvoo created a brief personal literature unique in the corpus of her works. Eliza Snow in Nauvoo was not the revered "Sister Snow," dynamic leader of Utah Mormon women, prominent as wife of President Brigham Young. In Nauvoo she was next to nobody. Her family, respected citi- zens in their Ohio home, were undistinguished in Mormon hierarchical circles. Lorenzo, who with his sister would eventually rise to promi- nence, was then a young bachelor missionary. Leonora, their older sister, separated from the father of her children, would marry Isaac Morley in early and secret polygamy; her obscurity was necessary. The Snow par- MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER is associate professor of English in the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History at Brigham Young University. She acknowledges here the suggestions of Frank McEntire, as useful a muse as ever descended from Parnassus on the Fourteenth Floor, and of Bruce Jorgenson, who commented on the original paper at its pre- sentation to the Mormon History Association, 8 May 1988. Thanks, as always, are due to Jill Mulvay Derr who, with the author, is currently preparing the collected poems of Eliza Snow for publication in 1990. -

More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women As Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2017 More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860 Kim M. (Kim Michaelle) Davidson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Davidson, Kim M. (Kim Michaelle), "More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans, 1830-1860" (2017). WWU Graduate School Collection. 558. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/558 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. More Than Faith: Latter-Day Saint Women as Politically Aware and Active Americans 1830-1860 By Kim Michaelle Davidson Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Jared Hardesty Dr. Hunter Price Dr. Holly Folk MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

In the Personal Journey of Eliza R. Snow

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 1 Article 7 1-1-1996 The Significance of “O My atherF ” in the Personal Journey of Eliza R. Snow Jill Mulvay Derr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Derr, Jill Mulvay (1996) "The Significance of “O My atherF ” in the Personal Journey of Eliza R. Snow," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Derr: The Significance of “O My Father” in the Personal Journey of Eliz eliza roxcy snow 1804 1887 daguerreotype taken about 1856 cour- tesy photographic archives harold B lee library brigham young uni- versityversity provo utah Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1996 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 36, Iss. 1 [1996], Art. 7 the significance of 0 my father in the personal journey of eliza R snow when eliza articulated her attachment to the eternal household where she dadbadresided and would yet dwell she defined the polestar by which she would orient herserherself the rest of her lifeiffie jill mulvay derr on january 21 1910 the relief society general presidency and board gathered for the first time in their rooms in the impos- ing four story bishops -

Imperial Zions: Mormons, Polygamy, and the Politics of Domesticity in the Nineteenth Century

Imperial Zions: Mormons, Polygamy, and the Politics of Domesticity in the Nineteenth Century By Amanda Lee Hendrix-Komoto A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan M. Juster, Co-Chair Associate Professor Damon I. Salesa, Co-Chair Professor Terryl L. Givens Associate Professor Kali A.K. Israel Professor Mary C. Kelley ii To my grandmother Naomi, my mother Linda, my sisters Laura and Jessica, and my daughter Eleanor iii Acknowledgements This is a dissertation about family and the relationships that people form with each other in order to support themselves during difficult times. It seems right, then, to begin by acknowledging the kinship network that has made this dissertation possible. Susan Juster was an extraordinary advisor. She read multiple drafts of the dissertation, provided advice on how to balance motherhood and academia, and, through it all, demonstrated how to be an excellent role model to future scholars. I will always be grateful for her support and mentorship. Likewise, Damon Salesa has been a wonderful co-chair. His comments on a seminar paper led me to my dissertation topic. Because of him, I think more critically about race. In my first years of graduate school, Kali Israel guided me through the politics of being a working-class woman at an elite academic institution. Even though my work took me far afield from her scholarship, she constantly sent me small snippets of information. Through her grace and generosity, Mary Kelley served as a model of what it means to be a female scholar.