British Racing Green 1946-1956 FIRST PUBLISHED 1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiskens Newsletter 2017

News from the Mews 1954 Jaguar XK120 Competition - 1954 Coupe des Alpes class winner INTRODUCTION 2017 HAS BEEN ANOTHER GREAT YEAR FOR We share with them a deep-seated love for the old car Fiskens, both from the Mews and on the track. We have world; be it from restoration of a beloved vintage sports enjoyed negotiating the sales of some of the greatest cars to car, to being lucky enough to rally and race at great events come to the market both publically and privately and our such as the Mille Miglia and the Goodwood Revival, as specialist service is in greater demand than ever. well as showing cars at the most important concours. We personally welcome a more sober, authentic and On behalf of all the team at Fiskens, we hope that you genuine world where our established long-term buyers are will enjoy our news from the Mews, and that you will visit clear to us; those who appreciate that we only consign for us on our stand at Rétromobile early in the new year and sale the very best available. come to our new state-of-the-art Mews showroom in 2018. 1954 Jaguar XK120 Competition - 1954 Coupe des Alpes class winner The Fiskens stand at Rétromobile 2017 RÉTROMOBILE IT IS NOT LONG NOW UNTIL OUR ANNUAL the variety of content is unrepeated elsewhere throughout pilgrimage to Paris and the Salon Rétromobile, which will the year. be held from 7-11 February, 2018. e show is expanding You will recently have received an invitation to consign to t Pavilions One, Two and ree at the Porte de your car to be part of our Rétromobile collection. -

2019-12-01 Newsletter with Landrover V4

N E W S L E T T E R Paradise Garage Legacy C-type Jaguar www.paradisegarage.com.au Jaguar Service and Maintenance Paradise Garage is Sydney’s leading independent Jaguar service centre. 30 years of continuous growth The Legacy Sports Car range of Jaguar motoring icons supporting Jaguar drivers and their cars wether it be …. C-Type, D-type, XK SS. the current series cars, the modern classics or the Heritage cars. Paul LukesLukes….creating a new era in modern classic motor car heritage production. Paul brings together the finest craftsmen and expertise internationally, directing and overseeing all aspects of each project production vehicle to exacting standards. NNNOW AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE The Paradise CC----typetype Jaguar is a faithful incarnation of the 1953 Le Man’s winning Jaguar C-type now ready for hand over. • We are centrally located between Sydney City and the airport, close to transport links and Eastern The specifications of the build uses an original 1953 3.4 Litre Jaguar XK120 engine fully reworked to new condition with twin suburbs sandcast S.U. carburettors. • fixed price maintenance service programs to suit both your car and your driving High compression pistons and fast road cams all mated to a • Pre-warranty expiry checks syncromesh 5-speed gearbox and a traditional Jaguar independent • loan cars available rear suspension. Fitted with 4 wheel disc brakes and servo assist, • complimentary valet wash on every visit A.D.R. harness seat belts, collapsible steering column, 16” Dunlop • Paradise Garage Service History Record wire wheels with Blockley radial tyres all give a modern feel for the driver. -

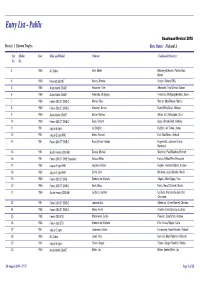

REV Entry List

Entry List - Public Goodwood Revival 2018 Race(s): 1 Kinrara Trophy - Race Status: National A Car Shelter Year Make and Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) No. No. 3 1963 AC Cobra Hunt, Martin Blakeney-Edwards, Patrick/Hunt, Martin 4 1960 Maserati 3500GT Rosina, Stefano Rosina, Stefano/TBC, 5 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Alexander, Tom Alexander, Tom/Wilmott, Adrian 6 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Friedrichs, Wolfgang Friedrichs, Wolfgang/Hadfield, Simon 7 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Werner, Max Werner, Max/Werner, Moritz 8 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Allemann, Benno Dowd, Mike/Gnani, Michael 9 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Mosler, Mathias Gillian, G.C./Woodgate, Chris 10 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Gaye, Vincent Gaye, Vincent/Reid, Anthony 11 1961 Jaguar E-type Ian Dalglish Dalglish, Ian/Turner, James 12 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Meins, Richard Huff, Rob/Meins, Richard 14 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Racing Team Holland Hugenholtz, John/van Oranje, Bernhard 15 1961 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Darcey, Michael Woolmer, Paul/Woolmer, Richard 16 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB 'Breadvan' Halusa, Niklas Halusa, Niklas/Pirro, Emanuele 17 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Hayden, Andrew Hayden, Andrew/Hibberd, Andrew 18 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Corrie, John Minshaw, Jason/Stretton, Martin 19 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Scuderia del Viadotto Vögele, Alain/Vögele, Yves 20 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Devis, Marc Devis, Marc/O'Connell, Martin 21 1960 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Le Blanc, Karsten Le Blanc, Karsten/van Lanschot, Christiaen 23 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Lanzante Ltd. Ellerbrock, Olivier/Glaesel, Christian -

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30

Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2 Tuesday 14 May 2013 10:30 Graham Budd Auctions Ltd Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Graham Budd Auctions Ltd (Two Day Sporting Memorabilia Auction - Day 2) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 335 restrictions and 144 meetings were held between Easter 1940 Two framed 1929 sets of Dirt Track Racing cigarette cards, and VE Day 1945. 'Thrills of the Dirt Track', a complete photographic set of 16 Estimate: £100.00 - £150.00 given with Champion and Triumph cigarettes, each card individually dated between April and June 1929, mounted, framed and glazed, 38 by 46cm., 15 by 18in., 'Famous Dirt Lot: 338 Tack Riders', an illustrated colour set of 25 given with Ogden's Post-war 1940s-50s speedway journals and programmes, Cigarettes, each card featuring the portrait and signature of a including three 1947 issues of The Broadsider, three 1947-48 successful 1928 rider, mounted, framed and glazed, 33 by Speedway Reporter, nine 1949-50 Speedway Echo, seventy 48cm., 13 by 19in., plus 'Speedway Riders', a similar late- three 1947-1955 Speedway Gazette, eight 8 b&w speedway 1930s illustrated colour set of 50 given with Player's Cigarettes, press photos; plus many F.I.M. World Rider Championship mounted, framed and glazed, 51 by 56cm., 20 by 22in.; sold programmes 1948-82, including overseas events, eight with three small enamelled metal speedway supporters club pin England v. Australia tests 1948-53, over seventy 1947-1956 badges for the New Cross, Wembley and West Ham teams and Wembley -

REV Entry List

Entry List Goodwood Revival 2019 Race(s): 1 Kinrara Trophy presented by Hackett - For closed-cockpit GT cars, of three litres and over, of a type that raced before 1963 Race Status: National A Car Shelter Year Make and Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) No. No. 1 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Macari, Joe Kristensen, Tom/Macari, Joe 2 1962 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Evans, Chris/Livingstone, Ian Cottingham, James/TBC, 3 1962 AC Cobra Lovett, Paul Bryant, Oliver/Sergison, Ewen 4 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Racing Team Holland Franchitti, Dario/Hugenholtz, John 5 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Alexander, Tom Alexander, Tom/Le Blanc, Karsten 6 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Friedrichs, Wolfgang Hadfield, Simon/Turner, Darren 7 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Gaye, Vincent Gaye, Vincent/Twyman, Joe 8 1963 Austin-Healey 3000 Steinke, Thomas Draper, Julien/Steinke, Thomas 9 1961 Jaguar E-type Coombs Automotive Graham, Stuart/March, Charlie 10 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Müller, Urs Müller, Arlette/Müller, Urs 11 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Devis, Marc Devis, Marc/O'Connell, Martin 12 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO FICA FRIO Ltd Monteverde, Carlos/Pearson, Gary 14 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Meins, Richard Bentley, Andrew/Meins, Richard 15 1961 Jaguar E-type Lindemann, Adam Lindemann, Adam/Meaden, Richard 16 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Midgley, Mark Lockie, Calum/Midgley, Mark 17 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Hayden, Andrew Hayden, Andrew/Hibberd, Andrew 18 1964 Jaguar E-type FHC Hart, David Hart, David/Hart, Olivier 20 1962 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Dumolin, Christian Dumolin, Christian/Thibaut, Pierre-Alain 21 1960 -

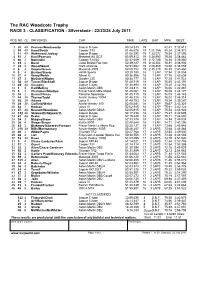

SC2011 WT Results

The RAC Woodcote Trophy RACE 3 - CLASSIFICATION - Silverstone - 22/23/24 July 2011 POS NO CL DRIVER(S) CAR TIME LAPS GAP MPH BEST 1 20 4A Pearson/Monteverde Jaguar D-type 50:24.823 19 82.41 2:32.612 2 54 4A Hood/Smith Cooper T33 51:46.578 19 1:21.755 80.24 2:34.372 3 11 4A Wakeman/Lindsay Jaguar D-type 51:58.395 19 1:33.572 79.94 2:37.596 4 51 2 Huni/Pearson Maserati A6 GCS 51:59.813 19 1:34.990 79.90 2:38.462 5 60 2 Mann/Ure Cooper T24/25 52:37.609 19 2:12.786 78.94 2:39.860 6 85 2 Bond Lister Bristol Flat Iron 52:39.127 19 2:14.304 78.91 2:38.902 7 23 4 Wood/Wood RGS Atalanta 52:51.692 19 2:26.869 78.59 2:38.059 8 6 3 Vogele/Green Maserati 300S 53:00.102 19 2:35.279 78.39 2:40.460 9 3 4 Buxton/Steele HWM Sports 50:29.700 18 1 LAP 77.94 2:38.056 10 57 4 Verey/Welch Allard J2 50:36.906 18 1 LAP 77.76 2:42.834 11 47 3 McGuire/Wigley Gordini 23S 50:58.777 18 1 LAP 77.20 2:41.922 12 58 4A Turner/Blackhall Jaguar D-type 51:20.719 18 1 LAP 76.65 2:43.191 13 49 4A Cussons Jaguar C-type 51:38.894 18 1 LAP 76.20 2:42.744 14 1 3 Hall/Melling Aston Martin DB3 51:44.811 18 1 LAP 76.06 2:42.481 15 4 2 Champion/Stretton Frazer Nash Mille Miglia 51:45.061 18 1 LAP 76.05 2:44.177 16 38 2 Burnett/Ames Porsche Speedster 51:45.710 18 1 LAP 76.03 2:46.143 17 44 3A Thorne/Todd Austin Healey 100M 51:46.328 18 1 LAP 76.02 2:46.314 18 10 3A Adams Lotus X 51:49.703 18 1 LAP 75.94 2:39.267 19 29 3A Corfield/Welch Austin-Healey 100 52:00.681 18 1 LAP 75.67 2:42.324 20 62 1 Hodson Lotus VI 52:02.915 18 1 LAP 75.61 2:40.122 21 27 3A Bennett/Woodgate Aston Martin -

1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review

1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review The year was 1935 when the Jaguar brand first leapt out of the factory gates. Founded in 1922 as the Swallow Sidecar Company by William Lyons and William Walmsley, both were motorcycle enthusiasts and the company manufactured motorcycle sidecars and automobile bodies. Walmsley was rather happy with the company’s modest success and saw little point in taking risks by expanding the firm. He chose to spend more and more time plus company money on making parts for his model railway instead. Lyons bought him out with a public stock offering and became the sole Managing Director in 1935. The company was then renamed to S.S. Cars Limited. After Walmsley had left, the first car to bear the Jaguar name was the SS Jaguar 2.5l Saloon released in September 1935. The 2.5l Saloon was one of the most distinctive and beautiful cars of the pre-war era, with its sleek, low-slung design. It needed a new name to reflect these qualities, one that summed up its feline grace and elegance with such a finely-tuned balance of power and agility. The big cat was chosen, and the SS Jaguar perfectly justified that analogy. A matching open-top two-seater called the SS Jaguar 100 (named 100 to represent the theoretical top speed of 100mph) with a 3.5 litre engine was also available. www.themodelcarcritic.com | 1 1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review 1935 SS Jaguar 2.5l Saloon www.themodelcarcritic.com | 2 1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review 1936 SS Jaguar 100 On 23rd March 1945, the shareholders took the initiative to rename the company to Jaguar Cars Limited due to the notoriety of the SS of Nazi Germany during the Second World War. -

ICI Paint Reference

LOTUS Pinchin, Johnson ICI Paint Nexa PPG Glasuri DESCRIPTION DATES NOTE COLOUR Paint Reference Reference Autocolor Code t Code CODE (Lotus part (Lotus part Code NUMBER number below) number below) None NK ICI P0303192 3192 PPG NK Medici Blue ? An original S1 option, but had no Lotus code. Was a Standard CBG308 concept Triumph colour, ref 378TR. Ditzler 12163 PPG: Powder Blue formula 12163; Martin Senour: Powder Blue 25105; ICI: Powder Blue per pint: 8013. From workshop manual for the Lotus Elan 1600 (ie S1). DMC900 - Page A5 Body equipment Carpeting-Rubber press stud fixing 446.8 to floor. Trim-washable PVC. Colours interior trim-Atlas Grey DMC904 - and Light Tan, seats available in Black,Tan and Grey Body 83.5 colours Fiesta Yellow, Carmen Red, Medici Blue, Cirrus White DMC937 - and British Racing Green Ashtrays Indoor trim, both sides 40.9 DMC901 - None NK ICI P0303097 3097 NK NK Carmen Red ? An original S1 option, but had no Lotus code. Was a Jaguar GR227 colour None NK ICI P0303484 YL11 NK NK Fiesta Yellow ? An original S1 option, but had no Lotus code. Was an Austin colour None NK NK NK NK NK Ford Sunburst Yellow ? An original S1 option, but had no Lotus code. Also an Elite colour. Elite Colours were: Jan 62: Sunburst Yellow, Tartan Red, Cirrus White, SE Models had silver roof section. Earlier: Cobalt Blue, Lime Green, BRG, Deep Yellow, Silver None NK NK NK NK NK Spruce Green Early 70-Jan 73 A BMC colour (GN-13BMC), offered on some Federal Elans, per sales sheet records. -

Lack Nach Wahl Colour to Sample 20150225.Pdf

Außenfarbe nach Wahl / Exterior color to sample Farbbezeichnung Farbcode uni metallic color name color code '98' '99' 911 / Boxster Cayman Panamera changes absolutrot / Absolute Red Y3F ? achatgraumetallic / Agate Grey Metallic M7S aetnablau / Etna Blue Y31 amarantrot / Amaranth Red ??? ? amazonasgrünmetallic / Amazonas Green Metallic 37Z FF? amethystmetallic / Amethyst Metallic M4Z ? anthrazitbraunmetallic / Anthracite Brown Metallic M8S ?? apricotbeige / Apricot Beige 548 ? aquablaumetallic / Aqua Blue Metallic M5R aquamarineblaumetallic / Aquamarine Blue Metallic W33 ? aquamarine Z62 arenarotmetallic / Arena Red Metallic 84S arktissilbermetallic / Artic Silver Metallic 92U ? atakamagelb / Atakama Yellow Y30 ? atlasgraumetallic / Atlas Grey Metallic M7X aubergine 025 ? ? F F ? auratiumgrünmetallic / Auratium Green Metallic ? FF? aventuragrünmetallic / Aventura Green Metallic 39S ? azzurrocaliforniametallic 3F3 ?? azzurro tirreno W83 ? azzuro thetys metallic W53 ? ballonweiss / ballon white ? ? basaltschwarzmetallic / basalt black metallic C9Z blaumetallic / Blue Metallic 334 ? brewstergreen / Brewster Green 22B blucaelum metallic LY5Q ? blue francia metallic W29 ? blutorange / Tangerine ??? ? britishracinggreen / British Racing Green 21D carbongraumetallic / Carbon Grey Metallic M9Z ? carbonschwarzmetallic / Carbon Black Metallic 7C3 ? carraraweiß / Carrara White B9A ? carraraweissmetallic / Carrara White Metallic S9R cashmere ???FF? cobaltblaumetallic / Cobalt Blue Metallic 3C8 -

VRCBC Vantage Winter 2013 2

VANTAGE Winter 2013 VRCBC Vantage Winter 2013 2 We are back! We haven’t had a In This Issue: Vantage issue for a while, that is what Geezer Central 2 happens when the editor is also the President’s Report 3 chair of the British Columbia Historic BCHMR It rained 4 Motor Races. Mike Tate 6 We had had a good 2013 season President Stan’s Europe 8 with an active REVS series and pretty GVMPS Inductees 10 good BCHMR It rained unfortunately. Fairservice on Donald Healey 11 See details later. Tom’s photo Page 15 The Book 17 Photo Contest 18 About VRCBC 18 Your Editor at Work You can contact me at [email protected] or by phone at 604 922 2722 Vintage Racing Club of British Columbia, 3366 Baird Road, North Vancouver, BC, V7K 2G7 Tel: 604 980 7750, Email: [email protected], Web www.vrcbc.ca VRCBC Vantage Winter 2013 3 President’s Message That dramatic Jock Hobson photo of Dennis Repel ventilating the engine in his Heavy Chevy Camaro on the Mission front straight is actually from 2012. But it is so cool that Editor Tom decided to put it on the cover of this final 2013 edition of Vantage regard- less. After all, one of the things VRCBC members like to do is to commemorate memorable motorsport moments from history; even if in this case the history is only one year old! Thanks to Jock (and Dennis too of course) for this great ‘visual’. Speaking of remembering the past, President Stan channels Jenson Button on the Brooklands Banking Janet and I had a chance to see a lot bution to the promotion of road racing of motorsport history when we visited that attract us to Vintage racing. -

Gateway Relay Vol IV, No

Gateway Relay Vol IV, No. 1 St Louis Sports Car Council September 2014 Council News & Notes Up & Coming Obviously there’s a chance 18 Sept 2014—Official launch of the Jaguar F-Type Coupe, sponsored by Plaza some heat and humidity may Jaguar, Gateway Motorsports Park, Madison, IL, 4-8 PM. Three professional racecar return, but when you figure drivers will take people on a ride around the road course. Come out for a fun evening Rapid City, the Black Hills for all including refreshments and hors d’oeuvres. and points north and west got 19 Sept 2014—ABBCS Welcome Parking Lot BBQ, Red Roof Westport, 11837 serious snow last week Lackland Rd. Traditional pre-show meet and greet hosted by the MG Club of St Lou- (thanks Alberta!), it would is, $5 donation to the cause requested, info at www.allbritishcarshow.com/home/. appear we are now into fall...which means leaves 20 Sept 2014—Cars & Coffee. LOCATION CHANGE: Westport Plaza, I-270 and turning and great driving Page Blvd, south lot between Starbucks and McDonalds, 8 AM to 10 AM. On Face- weather. book at https://www.facebook.com/events/1578786405680180/ Fall also means the last flurry 20 Sept 2014—33rd All British Car & Cycle Show, Creve Coeur Lake Park, featur- of activities; check “Up & ing Sunbeam as this year’s featured marque. Hosted by the MG Club of St Louis, Coming” to the right and/or food concession by St Louis Triumph Owners Association. Online registration availa- www.stlscc.org for the latest ble at www.allbritishcarshow.com/home/. -

ACES WILD ACES WILD the Story of the British Grand Prix the STORY of the Peter Miller

ACES WILD ACES WILD The Story of the British Grand Prix THE STORY OF THE Peter Miller Motor racing is one of the most 10. 3. BRITISH GRAND PRIX exacting and dangerous sports in the world today. And Grand Prix racing for Formula 1 single-seater cars is the RIX GREATS toughest of them all. The ultimate ambition of every racing driver since 1950, when the com petition was first introduced, has been to be crowned as 'World Cham pion'. In this, his fourth book, author Peter Miller looks into the back ground of just one of the annual qualifying rounds-the British Grand Prix-which go to make up the elusive title. Although by no means the oldest motor race on the English sporting calendar, the British Grand Prix has become recognised as an epic and invariably dramatic event, since its inception at Silverstone, Northants, on October 2nd, 1948. Since gaining World Championship status in May, 1950 — it was in fact the very first event in the Drivers' Championships of the W orld-this race has captured the interest not only of racing enthusiasts, LOONS but also of the man in the street. It has been said that the supreme test of the courage, skill and virtuosity of a Grand Prix driver is to w in the Monaco Grand Prix through the narrow streets of Monte Carlo and the German Grand Prix at the notorious Nürburgring. Both of these gruelling circuits cer tainly stretch a driver's reflexes to the limit and the winner of these classic events is assured of his rightful place in racing history.