Exercises in Soft Power and Cultural Diplomacy: the Cultural Programming of the Los Angeles and London Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masterplanning Public Memorials

This article was downloaded by: [University College London] On: 29 April 2015, At: 07:20 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Planning Perspectives Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rppe20 Masterplanning public memorials: an historical comparison of Washington, Ottawa and Canberra Quentin Stevensab a School of Architecture and Design, RMIT University, Building 100 Level 9, GPO Box 2476, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia b Bartlett School of Planning, University College London, London, UK Published online: 18 Mar 2014. Click for updates To cite this article: Quentin Stevens (2015) Masterplanning public memorials: an historical comparison of Washington, Ottawa and Canberra, Planning Perspectives, 30:1, 39-66, DOI: 10.1080/02665433.2013.874956 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2013.874956 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Versions of published Taylor & Francis and Routledge Open articles and Taylor & Francis and Routledge Open Select articles posted to institutional or subject repositories or any other third-party website are without warranty from Taylor & Francis of any kind, either expressed or implied, including, but not limited to, warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. -

Cultural Diplomacy and the National Interest

Cultural Diplomacy and The National Interest Cultural Diplomacy and The National Interest: In Search of a 21st-Century Perspective Overview Interest in public and cultural diplomacy, after a long post-Cold War decline, has surged in the last few years. This new focus inside and outside government has two causes: first, the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the perception that the U.S. is losing a war of culture against Islamic extremists; and second, the documented global collapse of positive public sentiment toward the U.S. But the task facing policy leaders – translating interest into action – must accommodate the reality that government cultural work has been diminished in scope even as trade in cultural products and Internet communication has increased the complexity and informal character of cross-cultural communication. The current state of U.S. cultural and public diplomacy has been reviewed by numerous special commissions and elite bodies, ranging from the 9/11 Commission to the RAND Corporation, from Congress’s Governmental Accountability Office (GAO) to the Council on Foreign Relations. Resulting recommendations have emphasized increased funding, better coordination, increased State Department programming, and more private-sector partnership to support programming that the State Department and governmental broadcasting outlets are already producing. However, because cultural work constitutes a long-term, diffuse, and largely immeasurable solution to a pressing problem in an age of quick fixes, the larger concept of cultural diplomacy – defined most broadly as the propagation of American culture and ideals around the world – tends to get short shift in these presentations. In addition, the lion’s share of The Curb Center for Art, American cultural content is conveyed by private-sector film, recording, and Enterprise, and Public Policy at Vanderbilt broadcasting industries, functioning beyond the realm of official policy objectives. -

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: a “How To” Manual *

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: A “How To” Manual * Daniel Byman and Matthew Kroenig Security Studies (forthcoming, June 2016) *For helpful comments on earlier versios of this article, the authors would like to thank Michael C. Desch, Rebecca Friedman, Bruce Jentleson, Morgan Kaplan, Marc Lynch, Jeremy Shapiro, and participants in the Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security Speaker Series at the University of Chicago, participants in the Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Launch Conference, Austin, Texas, October 17-19, 2013, and members of a Midwest Political Science Association panel. Particular thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Security Studies for their helpful comments. 1 Joseph Nye, one of the rare top scholars with experience as a senior policymaker, lamented “the walls surrounding the ivory tower never seemed so high” – a view shared outside the academy and by many academics working on national security.1 Moreover, this problem may only be getting worse: a 2011 survey found that 85 percent of scholars believe the divide between scholars’ and policymakers’ worlds is growing. 2 Explanations range from the busyness of policymakers’ schedules, a disciplinary shift that emphasizes theory and methodology over policy relevance, and generally impenetrable academic prose. These and other explanations have merit, but such recommendations fail to recognize another fundamental issue: even those academic works that avoid these pitfalls rarely shape policy.3 Of course, much academic research is not designed to influence policy in the first place. The primary purpose of academic research is not, nor should it be, to shape policy, but to expand the frontiers of human knowledge. -

Nov 2014 Dummy.Indd

NOVEMBERJULY 20102014 •• TAXITAXI INSIDERINSIDER •• PAGEPAGE 11 INSIDER VOL. 15, NO. 11 “The Voice of the NYC Transportation Industry.” NOVEMBER 2014 Letters Start on Page 3 EDITORIAL • By David Pollack Insider News Page 5 • Taxi Drivers and Ebola Updated Relief Stands Thankfully there is a radio show where you can Taxi Dave (that’s me!) not only had the Chairwoman get fi rst hand information needed to answer any of of the TLC, Meera Joshi discuss fears of the Ebola Page 6 your questions whether industry related or even virus, but I had Dr. Jay Varma, a spokesperson from • health related. the NYC Department of Health answering all ques- Taxi Attorney Before we get into Ebola, TLC Chair- tions that drivers brought to “Taxi Dave’s” By Michael Spevack woman Joshi stated that the TLC will attention. How does Ebola spread? What be sending out warning letters to drivers is the best means of prevention and pro- Page 7 instead of summonses for a red light tection? • camera offense. “Vision Zero is not Chairwoman Joshi stated, “Thank you How I Became A Star about penalties,” she stated. To hear this for reaching out to the Department of By Abe Mittleman and much more, listen to this link: http:// Health. The myth of how Ebola spreads is www.wor710.com/media/podcast-the- spreading incredibly faster than the actual Page 15 taxi-dave-show-TaxiInsider/the-taxi-dave- disease ever could. It is really important to • show-102614-25479519/ separate facts from fi ction and the Depart- Street Talk Folks, if you want fi rst hand infor- ment of Health has been doing an amazing By Erhan Tuncel mation, every Sunday evening at 8:00 job in getting that message out there and PM listen to WOR-710 radio to TAXI DAVE. -

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park: an Assessment of the 2012 London Games Legacies Simona Azzali*

Azzali City Territ Archit (2017) 4:11 DOI 10.1186/s40410-017-0066-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park: an assessment of the 2012 London Games Legacies Simona Azzali* Abstract The London 2012 Olympics were the frst Games with a legacy plan already in execution well before the beginning of the event. This study aims at evaluating the legacies of this Olympic edition, with particular regard to the new public open spaces created and their sustainability. The research carries out a post-occupancy evaluation of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, which is the main output of the 2012 Summer Olympics. Results show good achievements in terms of physical and social integration while the economic impact appears to be the weakest legacy from hosting the Games. Keywords: Olympic Legacies, Mega sports events, London 2012, Sustainable open spaces, Legacy planning Background the frst hosting city with a comprehensive legacy plan Mega-events, from the Olympics to the World Cups, are that was already in execution before the staging of the often regarded by planners and politicians as key driv- Games (Chappelet 2008). Indeed, in 2003, the Olympic ers for the overall redevelopment of a city (Azzali 2017; Committee amended its charter to include an additional Malfas et al. 2004). Mega-events have driven the urban statement in its mission that focused on the generation transformation of cities such as Barcelona, London, Rio, of benefcial legacies for hosting cities. Since 2003, all Beijing, and Shanghai, but while the prospect of eco- bidding cities are required to have a legacy plan in their nomic growth is the driving force for hosting a major candidacy fles, explaining post event usage for sports event, the legacies that follow their hosting have been dif- facilities and long-term plans for the areas involved in the fcult to design and quantify (Preuss 2007). -

The Use of Cultural Diplomacy by Brazilian Government Abstract The

1 Building a new strategy: the use of Cultural Diplomacy by Brazilian Government Abstract The paper will explore the co-relation between diplomacy and culture when States seek for power in the international arena. We postulate that countries with an interest to push the current power structure – and change today’s established order – can try to use cultural assets to enforce their own interests and values at the international arena. Considering that culture becomes an apparatus to achieve power and transform international society, we hypothesize that emerging powers - introduced lately at International Society - could articulate their positions by associating culture and diplomacy – an essential institution of international society. The instrumentalization of culture by Cultural Diplomacy contributes to these countries becoming more reputable in the international environment and tends to re- structure the balance of power. We propose to use the Brazilian case to illustrate our proposition. In this way, the paper will especially work with literature about International Cultural Relations and its intersection with Cultural History. The works of Robert Frank, Pascal Ory and Anaïs Fléchét will offer the main contribution for this argument. Introduction The research presented here intends to be a contribution to International Relations research field, especially by incorporating elements of Cultural History and by reflection on identity issues and on Brazilian international projection in the twenty-first century. Thus, from the study of the Brazilian cultural diplomacy strategies in the beginning of this century – period of major changes in the organization of international relations of Brazil –, we aim to demonstrate how countries considered ‘emerging poles’ (LIMA, 2010) can and make use of mechanisms created by States established in International Society. -

The Role of Study-Abroad Students in Cultural Diplomacy: Toward an International Education As Soft Action Madalina Akli, Ph.D

International Research and Review: Journal of Phi Beta Delta Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2012 Honor Society for International Scholars ISSN: 2167-8669 Publication URL: http://www.phibetadelta.org/publications.php The Role of Study-Abroad Students in Cultural Diplomacy: Toward an International Education as Soft Action Madalina Akli, Ph.D. Rice University Abstract This paper argues that study-abroad students should be at the center of cultural diplomacy. It recognizes that students can engage in soft action to establish intercultural dialogue. They develop and sustain relationships with people from host countries through cultural immersion and education. Study-abroad students are encouraged to proactively claim their cultural diplomacy role, and thereby cause a shift from formal soft power, traditionally concentrated in embassies and the diplomatic corps, to informal soft action in daily life abroad. With the recent development of a plethora of study-abroad opportunities, soft power can be re-configured by students and educators who cross national borders. Consequently, they are the potential agents of a paradigm shift regarding cultural diplomacy and international education: they are today’s new unofficial cultural diplomats. Key words: international education, study abroad, student cultural ambassadors, cultural diplomacy, soft action A Brief Historical Overview of U.S. International Education: A Diversity of Rationales and Purposes From a historical perspective, the development of international education from 1945 to 1970, although dynamic, -

The Olympic Games and Civil Liberties

Analysis A “clean city”: the Olympic Games and civil liberties Chris Jones Introduction In 2005, the UK won the right to host the 2012 Olympic Games. Seven years later, the Games are due to begin, but they are not without controversy. Sponsors of the Games – including McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, Cadbury’s, BP and, perhaps most controversially, Dow Chemical [1] – were promised “what is chillingly called a ‘clean city’, handing them ownership of everything within camera distance of the games.” [2] In combination with measures put in place to deal with what have been described as the “four key risks” of terrorism, protest, organised crime and natural disasters, [3] these measures have led to a number of detrimental impacts upon civil liberties, dealt with here under the headings of freedom of expression; freedom of movement; freedom of assembly; and the right to protest. The Games will be hosted in locations across the country, but primarily in London, which is main the focus of this analysis. Laying the groundwork Following victory for the bid to host the Games, legislation – the London Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Act 2006 – was passed “to make provision in connection with the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games that are take place in London in the year 2012.” [4] It is from here that limitations on freedom of expression have come, as well as some of the limitations on freedom of movement that stem from the introduction of “Games Lanes” to London’s road system. Policing and security remains the responsibility of the national and local authorities. -

The Garden of Australian Dreams: the Moral Rights of Landscape Architects

EDWARD ELGAR THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS: THE MORAL RIGHTS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DR MATTHEW RIMMER SENIOR LECTURER ACIPA, FACULTY OF LAW, THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACIPA, Faculty Of Law, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 0200 Work Telephone Number: (02) 61254164 E-Mail Address: [email protected] THE GARDEN OF AUSTRALIAN DREAMS: THE MORAL RIGHTS OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS DR MATTHEW RIMMER* * Matthew Rimmer, BA (Hons)/ LLB (Hons) (ANU), PhD (UNSW), is a Senior Lecturer at ACIPA, the Faculty of Law, the Australian National University. The author is grateful for the comments of Associate Professor Richard Weller, Tatum Hands, Dr Kathy Bowrey, Dr Fiona Macmillan and Kimberlee Weatherall. He is also thankful for the research assistance of Katrina Gunn. 1 Prominent projects such as National Museums are expected to be popular spectacles, educational narratives, tourist attractions, academic texts and crystallisations of contemporary design discourse. Something for everyone, they are also self-consciously set down for posterity and must at some level engage with the aesthetic and ideological risks of national edification. Richard Weller, designer of the Garden of Australian Dreams1 Introduction This article considers the moral rights controversy over plans to redesign the landscape architecture of the National Museum of Australia. The Garden of Australian Dreams is a landscaped concrete courtyard.2 The surface offers a map of Australia with interwoven layers of information. It alludes to such concepts as the Mercator Grid, parts of Horton’s Map of the linguistic boundaries of Indigenous Australia, the Dingo Fence, the 'Pope’s Line', explorers’ tracks, a fibreglass pool representing a suburban swimming pool, a map of Gallipoli, graphics common to roads, and signatures or imprinted names of historical identities.3 There are encoded references to the artistic works of iconic Australian painters such as Jeffrey Smart, Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, and Gordon Bennett. -

Reflections on the Cultural Olympiad and London 2012 Festival

Photo Credits: Inside front cover – Battle For The Winds ©Maisie Hill; Page 2 – Peace Camp © Paul Lindsay/Chris Hill Photographic; Page 5 – Piccadilly Circus Circus © Matthew Andrews; Page 6 – BBC Radio 1’s Hackney Weekend - Florence and the Machine 2012 © BBC/Getty Images; Page 8 – Creating The Spectacle! © Norman Lomax, Moving Content; Page 9 – Rio Occupations © Ellie Kurttz; Page 9 – Africa Express © Simon Phipps; Page 10 – Mittwoch Aus Licht Birmingham Opera © Helen Maybanks; Page 11 – Overworlds and Underworlds - the Brothers Quay and Leeds Canvas © Tom Arber; Page 12 – Big and Small ©Lisa Tomasetti ; Page 14 – Battle for theWinds © Kevin Clifford; Page 16 – Anna Terasa Tanks ©?; Page 18 – BBC Radio 1’s Hackney Weekend 2012 - Jay-Z © BBC/Getty Images; Page 20 – Much Ado About Nothing © Jillian Edelstein; Page 23 – Speed of Light © Sally Jubb; Page 28 – Richard III © Marc Brenner; Page 30 – Branches: The Nature of Crisis © Joel Fildes REFLECTIONS ON THE CULTURAL OLYMPIAD AND THE LONDON 2012 FESTIVAL 01 CONTENT INTRODUCTION BY TONY HALL Chair of Cultural Olympiad Board 02 ONCE IN A LIFETIME Summary of Cultural Olympiad 04 THE CULTURAL OLYMPIAD AND LONDON 2012 FESTIVAL EVALUATION 18 02 REFLECTIONS ON THE CULTURAL OLYMPIAD AND THE LONDON 2012 FESTIVAL INTRODUCTION BY TONY HALL, CHAIR OF CULTURAL OLYMPIAD BOARD When London won the bid for the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, we promised that this ‘once in a lifetime’ event would include a great cultural programme involving people all over the UK. When we are asked why, we go back to the example of Ancient Greece, where the Olympic Games included artists alongside athletes. -

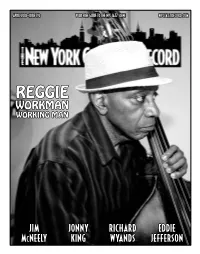

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

Andy Warhol Exhibit American Fare Summer Sets

NYC ® Monthly JULY 2015 JULY 2015 JULY NYC MONTHLY.COM VOL. 5 NO.7 VOL. AMERICAN FARE AMERICAN CUISINE AT ITS FINEST SUMMER SETS HEADLINING ACTS YOU CAN'T MISS ANDY WARHOL EXHIBIT AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART B:13.125” T:12.875” C M Y K S:12.75” The Next Big Thing Is Here lated. Appearance of device may vary. B:9.3125” S:8.9375” T:9.0625” The world’s frst dual-curved smartphone display Available now. Learn more at Samsung.com/GS6 ©2015 Samsung Electronics America, Inc. and Galaxy S are trademarks of Co., Ltd. Screen images simu FS:6.3125” FS:6.3125” F:6.4375” F:6.4375” 304653rga03_HmptMnthy TL Project Title: US - GS6_2015_S5053 Job Number: S5053 Executive Creative Director: None E.C.D. C.D. A.C.D A.D. C.W. Creative Director: None Client: SAMSUNG Bleed: 13.125” x 9.3125” Associate Creative Director: None Media: MAGAZINE Trim 1: 12.875” x 9.0625” Art Director: None Photographer: None Trim 2: None Copywriter: None Art Buyer: None STUDIO PRODUCTION IA PRODUCER ACCOUNT EX. ART BUYER Illustrator: None Live: 12.75” x 8.9375” Print Production: None Insertion Date: None Gutter: 0.125” Studio Manager: None Account Executive: None Traffic: None Publications/Delivery Company: Hamptons Monthly FILE IS BUILT AT: 100% THIS PRINT-OUT IS NOT FOR COLOR. 350 West 39th Street New York, NY 10018 212.946.4000 Round: 1 Version: C PACIFIC DIGITAL IMAGE • 333 Broadway, San Francisco CA 94133 • 415.274.7234 • www.pacdigital.com Filename:304653rga03_HmptMnthy.pdf_wf02 Operator:SpoolServer Time:13:37:40 Colors:Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Date:15-05-06 NOTE TO RECIPIENT: This file is processed using a Prinergy Workflow System with an Adobe Postscript Level 3 RIP.