Runs of Homozygosity in Sub-Saharan African Populations Provide Insights Into a Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus K Envelope Transcripts in Human Breast Cancer1

Vol. 7, 1553–1560, June 2001 Clinical Cancer Research 1553 Advances in Brief Expression of Human Endogenous Retrovirus K Envelope Transcripts in Human Breast Cancer1 Feng Wang-Johanning, Andra R. Frost, breast tumor sample showed nucleotide sequence differ- Gary L. Johanning, M. B. Khazaeli, ences, suggesting that multiple loci may be transcribed. Conclusions: These data indicate that HERV-K tran- Albert F. LoBuglio, Denise R. Shaw, and scripts with coding potential for the envelope region are 2 Theresa V. Strong expressed frequently in human breast cancer. The Comprehensive Cancer Center and Division of Hematology Oncology, Departments of Medicine [F. W-J., M. B. K., A. F. L., Introduction D. R. S., T. V. S.], Pathology [A. R. F.], and Nutrition Sciences 3 [G. L. J.], University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, HERVs are stably inherited sequences thought to have Alabama 35294-3300 entered the germ line of their host more than a million years ago (1, 2). These elements are widely dispersed throughout the genome and are estimated to comprise Ͼ1% of the entire human Abstract genome. Most HERVs are defective because of multiple termi- Purpose: We investigated the expression of human en- nation codons and deletions (3), but some appear to contain all dogenous retroviral (HERV) sequences in breast cancer. structural features necessary for viral replication (4). HERVs are Experimental Design: Reverse transcription-PCR (RT- grouped into single- and multiple-copy families, usually classi- PCR) was used to examine expression of the envelope (env) fied according to the tRNA used for reverse transcription (2). region of ERV3, HERV-E4-1, and HERV-K in breast cancer The type K family (HERV-K) is present in an estimated 30–50 cell lines, human breast tumor samples, adjacent uninvolved copies/human genome and includes some elements with long breast tissues, nonmalignant breast tissues, and placenta. -

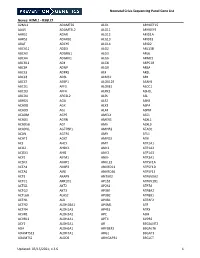

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

How Relevant Are Bone Marrow-Derived Mast Cells (Bmmcs) As Models for Tissue Mast Cells? a Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Bmmcs and Peritoneal Mast Cells

cells Article How Relevant Are Bone Marrow-Derived Mast Cells (BMMCs) as Models for Tissue Mast Cells? A Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of BMMCs and Peritoneal Mast Cells 1, 2, 1 1 2,3 Srinivas Akula y , Aida Paivandy y, Zhirong Fu , Michael Thorpe , Gunnar Pejler and Lars Hellman 1,* 1 Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University, The Biomedical Center, Box 596, SE-751 24 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (Z.F.); [email protected] (M.T.) 2 Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Uppsala University, The Biomedical Center, Box 589, SE-751 23 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (G.P.) 3 Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Biochemistry, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7011, SE-75007 Uppsala, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-(0)18-471-4532; Fax: +46-(0)18-471-4862 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 29 July 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 17 September 2020 Abstract: Bone marrow-derived mast cells (BMMCs) are often used as a model system for studies of the role of MCs in health and disease. These cells are relatively easy to obtain from total bone marrow cells by culturing under the influence of IL-3 or stem cell factor (SCF). After 3 to 4 weeks in culture, a nearly homogenous cell population of toluidine blue-positive cells are often obtained. However, the question is how relevant equivalents these cells are to normal tissue MCs. By comparing the total transcriptome of purified peritoneal MCs with BMMCs, here we obtained a comparative view of these cells. -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Gene Expression Profiles Complement the Analysis of Genomic Modifiers of the Clinical Onset of Huntington Disease

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/699033; this version posted July 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Gene expression profiles complement the analysis of genomic modifiers of the clinical onset of Huntington disease Galen E.B. Wright1,2,3; Nicholas S. Caron1,2,3; Bernard Ng1,2,4; Lorenzo Casal1,2,3; Xiaohong Xu5; Jolene Ooi5; Mahmoud A. Pouladi5,6,7; Sara Mostafavi1,2,4; Colin J.D. Ross3,7 and Michael R. Hayden1,2,3* 1Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 2Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 3BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 4Department of Statistics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 5Translational Laboratory in Genetic Medicine (TLGM), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore; 6Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 7Department of Physiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore; 8Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Huntington disease (HD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that is caused by a CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene. In an attempt to identify genomic modifiers that contribute towards the age of onset of HD, we performed a transcriptome wide association study assessing heritable differences in genetically determined expression in diverse tissues, employing genome wide data from over 4,000 patients. -

High Mutation Frequency of the PIGA Gene in T Cells Results In

High Mutation Frequency of the PIGA Gene in T Cells Results in Reconstitution of GPI A nchor−/CD52− T Cells That Can Give Early Immune Protection after This information is current as Alemtuzumab-Based T Cell−Depleted of October 1, 2021. Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation Floris C. Loeff, J. H. Frederik Falkenburg, Lois Hageman, Wesley Huisman, Sabrina A. J. Veld, H. M. Esther van Egmond, Marian van de Meent, Peter A. von dem Borne, Hendrik Veelken, Constantijn J. M. Halkes and Inge Jedema Downloaded from J Immunol published online 2 February 2018 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2018/02/02/jimmun ol.1701018 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2018/02/02/jimmunol.170101 Material 8.DCSupplemental Why The JI? Submit online. by guest on October 1, 2021 • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2018 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. Published February 2, 2018, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1701018 The Journal of Immunology High Mutation Frequency of the PIGA Gene in T Cells Results in Reconstitution of GPI Anchor2/CD522 T Cells That Can Give Early Immune Protection after Alemtuzumab- Based T Cell–Depleted Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation Floris C. -

Biosynthesis and Deficiencies of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol

130 Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B 90 (2014) [Vol. 90, Review Biosynthesis and deficiencies of glycosylphosphatidylinositol † By Taroh KINOSHITA*1, (Communicated by Kunihiko SUZUKI, M.J.A.) Abstract: At least 150 different human proteins are anchored to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane via glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI). GPI preassembled in the endoplasmic reticulum is attached to the protein’s carboxyl-terminus as a post-translational modification by GPI transamidase. Twenty-two PIG (for Phosphatidyl Inositol Glycan) genes are involved in the biosynthesis and protein-attachment of GPI. After attachment to proteins, both lipid and glycan moieties of GPI are structurally remodeled in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Four PGAP (for Post GPI Attachment to Proteins) genes are involved in the remodeling of GPI. GPI- anchor deficiencies caused by somatic and germline mutations in the PIG and PGAP genes have been found and characterized. The characteristics of the 26 PIG and PGAP genes and the GPI deficiencies caused by mutations in these genes are reviewed. Keywords: glycosylphosphatidylinositol, glycolipid, post-translational modification, somatic mutation, germline mutation, deficiency glycolipid membrane anchors. GPI-APs are typical Introduction raft-associated proteins and tend to form homo- At least 150 different human proteins are post- dimers.3),4) GPI-APs can be released from the translationally modified by glycosylphosphatidylino- cell after cleavage by GPI-cleaving enzymes or sitol (GPI) at the carboxyl (C)-terminus.1),2) These GPIases.5)–8) These characteristics are critical for proteins are expressed on the cell surface by being the functions of individual GPI-APs and for embryo- anchored to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane genesis, neurogenesis, fertilization, and the immune via the phosphatidylinositol (PI) moiety and termed system.5),8)–11) GPI-anchored proteins (GPI-APs). -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

Improving the Detection of Genomic Rearrangements in Short Read Sequencing Data

Improving the detection of genomic rearrangements in short read sequencing data Daniel Lee Cameron orcid.org/0000-0002-0951-7116 Doctor of Philosophy July 2017 Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne Bioinformatics Division, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on archival quality paper Page i Abstract Genomic rearrangements, also known as structural variants, play a significant role in the development of cancer and in genetic disorders. With the bulk of genetic studies focusing on single nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions, structural variants are often overlooked. In part this is due to the increased complexity of analysis required, but is also due to the increased difficulty of detection. The identification of genomic rearrangements using massively parallel sequencing remains a major challenge. To address this, I have developed the Genome Rearrangement Identification Software Suite (GRIDSS). In this thesis, I show that high sensitivity and specificity can be achieved by performing reference-guided assembly prior to variant calling and incorporating the results of this assembly into the variant calling process itself. Utilising a novel genome-wide break-end assembly approach, GRIDSS halves the false discovery rate compared to other recent methods on human cell line data. A comparison of assembly approaches reveals that incorporating read alignment information into a positional de Bruijn graph improves assembly quality compared to traditional de Bruijn graph assembly. To characterise the performance of structural variant calling software, I have performed the most comprehensive benchmarking of structural variant calling software to date. -

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX MLL Partial Tandem Duplication Leukemia Cells Are Sensitive to Small Molecule DOT1L Inhibition

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX MLL partial tandem duplication leukemia cells are sensitive to small molecule DOT1L inhibition Michael W.M. Kühn, 1* Michael J. Hadler, 1* Scott R. Daigle, 2 Richard P. Koche, 1 Andrei V. Krivtsov, 1 Edward J. Olhava, 2 Michael A. Caligiuri, 3 Gang Huang, 4 James E. Bradner, 5 Roy M. Pollock, 2 and Scott A. Armstrong 1,6 1Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY; 2Epizyme, Inc., Cambridge, MA; 3The Compre - hensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH; 4Divisions of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH; 5Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; 6Department of Pe - diatrics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: [email protected] doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.115337 SUPPLEMENTAL METHODS, TABLES, RESULTS, AND FIGURE LEGENDS MLL-PTD leukemia cells are sensitive to small molecule DOT1L inhibition Michael J. Hadler1,*, Michael W.M. Kühn1,*, Scott R. Daigle3, Richard P. Koche1, Andrei V. Krivtsov1, Edward J. Olhava3, Michael A. Caligiuri4, Gang Huang5, James E. Bradner6, Roy M. Pollock3, and Scott A. Armstrong1,2 1Human Oncology and Pathogenesis Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; 2Department of Pediatrics, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA; 3Epizyme, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA; 4The Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; 5Divisions of Experimental Hematology and Cancer Biology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA; 6Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. -

Figure S1. Reverse Transcription‑Quantitative PCR Analysis of ETV5 Mrna Expression Levels in Parental and ETV5 Stable Transfectants

Figure S1. Reverse transcription‑quantitative PCR analysis of ETV5 mRNA expression levels in parental and ETV5 stable transfectants. (A) Hec1a and Hec1a‑ETV5 EC cell lines; (B) Ishikawa and Ishikawa‑ETV5 EC cell lines. **P<0.005, unpaired Student's t‑test. EC, endometrial cancer; ETV5, ETS variant transcription factor 5. Figure S2. Survival analysis of sample clusters 1‑4. Kaplan Meier graphs for (A) recurrence‑free and (B) overall survival. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan‑Meier method, and differences between sample cluster curves were analyzed by log‑rank test. Figure S3. ROC analysis of hub genes. For each gene, ROC curve (left) and mRNA expression levels (right) in control (n=35) and tumor (n=545) samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas Uterine Corpus Endometrioid Cancer cohort are shown. mRNA levels are expressed as Log2(x+1), where ‘x’ is the RSEM normalized expression value. ROC, receiver operating characteristic. Table SI. Clinicopathological characteristics of the GSE17025 dataset. Characteristic n % Atrophic endometrium 12 (postmenopausal) (Control group) Tumor stage I 91 100 Histology Endometrioid adenocarcinoma 79 86.81 Papillary serous 12 13.19 Histological grade Grade 1 30 32.97 Grade 2 36 39.56 Grade 3 25 27.47 Myometrial invasiona Superficial (<50%) 67 74.44 Deep (>50%) 23 25.56 aMyometrial invasion information was available for 90 of 91 tumor samples. Table SII. Clinicopathological characteristics of The Cancer Genome Atlas Uterine Corpus Endometrioid Cancer dataset. Characteristic n % Solid tissue normal 16 Tumor samples Stagea I 226 68.278 II 19 5.740 III 70 21.148 IV 16 4.834 Histology Endometrioid 271 81.381 Mixed 10 3.003 Serous 52 15.616 Histological grade Grade 1 78 23.423 Grade 2 91 27.327 Grade 3 164 49.249 Molecular subtypeb POLE 17 7.328 MSI 65 28.017 CN Low 90 38.793 CN High 60 25.862 CN, copy number; MSI, microsatellite instability; POLE, DNA polymerase ε.