Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage Assessment

HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT LAND ADJOINING PRINCES PARADE SEABROOK Lee Evans Partnership Ref: 08113 AUG 2014 Lee Evans Partnership LLP St John’s Lane, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 2QQ tel: 01227 784444 fax: 01227 819102 email:[email protected] web: www.lee-evans.co.uk 1 lee evans architecture 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.6 The former Guide emphasised the need for an assessment of the significance of any heritage 1.1 This statement has been prepared as a Heritage Assessment and part of a staged assessment asset, and its setting, where development is proposed, to enable an informed decision making of the development potential of land between Princes Parade and the Royal Military Canal in process. ‘Significance’ is defined, in the NPPF Glossary, as “the value of the heritage asset to Seabrook, Hythe. The proposal involves the siting of a new swimming pool and sports centre, following this and future generations because of its heritage interest. That interest may be archaeological, an identified need by the District Council, and an ‘enabling’ housing development together with an architectural, artistic, or historical. Significance derives not only from a heritage asset’s physical enlarged ‘Seabrook Primary School’ in which to replace the existing one-form entry school; a need as presence, but also its setting”. The setting of the heritage asset is also clarified in the Glossary as identified by Kent County Council. “the surroundings in which a heritage asset is experienced. Its extent is not fixed and may change as the asset and its surroundings evolve”. 1.2 Three locations for these combined facilities have been considered. -

Littlestone-On-Sea Car Park to Dymchurch Redoubt Coastal Access: Camber to Folkestone - Natural England’S Proposals

www.naturalengland.org.uk Chapter 4: Littlestone-on-Sea Car Park to Dymchurch Redoubt Coastal Access: Camber to Folkestone - Natural England’s Proposals Part 4.1: Introduction Start Point: Littlestone-on-Sea Car Park (grid reference: TR 08333 23911) End Point: Dymchurch Redoubt (grid reference: TR 12592 31744 ) Relevant Maps: 4a to 4g Understanding the proposals and accompanying maps: The Trail: 4.1.1 Follows existing walked routes, including public rights of way and Cycleways, throughout. 4.1.2 Follows the coastline closely and maintains good sea views. 4.1.3 Is aligned on a sea defence wall at the northern end of Littlestone-on-Sea, through St Mary’s Bay to Dymchurch Redoubt.. 4.1.4 In certain tide and weather conditions, it may be necessary to close flood gates along a 5km stretch of sea wall between Littlestone-on-Sea and Dymchurch to prevent flooding inland. Other routes are proposed landward of the seawall for such times when the trail is unavailable. See parts 4.1.10 to 4.1.12 for details. 4.1.5 This part of the coast includes the following sites, designated for nature conservation or heritage preservation (See map C of the Overview): Dungeness Special Area of Conservation (SAC) Dungeness, Romney Marsh and Rye Bay Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for its geological /wildlife interest Dungeness, Romney Marsh and Rye Bay Potential Special Protected Area (pSPA) Dungeness, Romney Marsh and Rye Bay Proposed Ramsar Site (pRamsar) We have assessed the potential impacts of access along the proposed route (and over the associated spreading room described below) on the features for which the affected land is designated and on any which are protected in their own right. -

MOD Heritage Report 2011 to 2013

MOD Heritage Report 2011-2013 Heritage in the Ministry of Defence Cover photograph Barrow Clump, Crown Copyright CONTENTS Introduction 4 Profile of the MOD Historic Estate 5 Case Study: RAF Spadeadam 6 World Heritage Sites 7 Condition of the MOD Historic Estate 8 Scheduled Monuments 8 Listed Buildings 9 Case Study: Sandhurst 10 Heritage at Risk 11 Case Study: Otterburn 12 Estate Development and Rationalisation 13 Disposals 13 Strategy, Policy and Governance 14 Management Plans, Heritage Assessments 14 Historic Crashed Aircraft 15 Case Study: Operation Nightingale 16 Conclusion 17 Annex A: New Listed Building Designations 19 New Scheduled Monument Designations 20 Annex B: Heritage at Risk on the MOD Estate 21 Annex C: Monuments at Risk Progress Report 24 MOD Heritage Report 2011-13 3 Introduction 1. The MOD has the largest historic estate within Government and this report provides commentary on its size, diversity, condition and management. This 5th biennial report covers the financial years 11/12 and 12/13 and fulfils the requirement under the DCMS/ English Heritage (EH) Protocol for the Care of the Government Estate 2009 and Scottish Ministers Scottish Historic Environment Policy (SHEP). It summarises the work and issues arising in the past two years and progress achieved both in the UK and overseas. 2. As recognised in the 2011 English Heritage Biennial Conservation Report, the MOD has fully adopted the Protocol and the requirements outlined in the SHEP. The requirements for both standards have been embedded into MOD business and reflected within its strategies, policies, roles and responsibilities, governance, management systems and plans and finally data systems. -

Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy

Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy Appendix 1: Theme 5f Defence – Camps, Training Grounds and Ranges PROJECT: Folkestone & Hythe District Heritage Strategy DOCUMENT NAME: Theme 5(f): Defence Heritage – Camps, Training Grounds and Ranges Version Status Prepared by Date V01 INTERNAL DRAFT F Clark 20.03.18 Comments – First draft of text. No illustrations. Needs to be cross-checked and references finalised. Current activities will need expanding on following further consultation with stakeholders. Version Status Prepared by Date V02 RETURNED DRAFT D Whittington 16.11.18 Update back from FHDC Version Status Prepared by Date V03 CONSULTATION S MASON 29.11.18 DRAFT Check and Title page added Version Status Prepared by Date V04 Version Status Prepared by Date V05 2 | P a g e Appendix 1, Theme 5(f) Defence Heritage – Camps, Training Grounds and Ranges 1. Summary At various points throughout their history, towns such as Folkestone, Hythe and Lydd have played an important military role and become major garrison towns. Large numbers of soldiers, officers and military families have been accommodated in various barrack accommodation within camps such as Shorncliffe and Sandling, or billeted across the local towns and villages. Training grounds and ranges have developed which have served important purposes in the training of troops and officers for the war effort and in the defence of this country. Together they are an important collection of assets relating to the defensive heritage of the District and in many cases, continue to illustrate the historical role that many towns played when the district was again physically and symbolically placed on the front-line during times of war and unrest. -

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

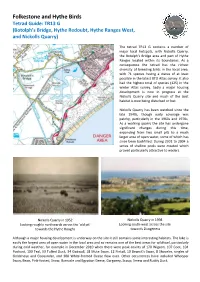

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

Landscape Assessment of Kent 2004

CHILHAM: STOUR VALLEY Location map: CHILHAMCHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTION North of Bilting, the Stour Valley becomes increasingly enclosed. The rolling sides of the valley support large arable fields in the east, while sweeps of parkland belonging to Godmersham Park and Chilham Castle cover most of the western slopes. On either side of the valley, dense woodland dominate the skyline and a number of substantial shaws and plantations on the lower slopes reflect the importance of game cover in this area. On the valley bottom, the river is picked out in places by waterside alders and occasional willows. The railway line is obscured for much of its length by trees. STOUR VALLEY Chilham lies within the larger character area of the Stour Valley within the Kent Downs AONB. The Great Stour is the most easterly of the three rivers cutting through the Downs. Like the Darent and the Medway, it too provided an early access route into the heart of Kent and formed an ancient focus for settlement. Today the Stour Valley is highly valued for the quality of its landscape, especially by the considerable numbers of walkers who follow the Stour Valley Walk or the North Downs Way National Trail. Despite its proximity to both Canterbury and Ashford, the Stour Valley retains a strong rural identity. Enclosed by steep scarps on both sides, with dense woodlands on the upper slopes, the valley is dominated by intensively farmed arable fields interspersed by broad sweeps of mature parkland. Unusually, there are no electricity pylons cluttering the views across the valley. North of Bilting, the river flows through a narrow, pastoral floodplain, dotted with trees such as willow and alder and drained by small ditches. -

Martello Towers of Romney Marsh

Introduction Martello Towers, sometimes known simply as Martellos, are small defensive forts that were built across the British Empire during the 19th century, from the time of the Napoleonic Wars onwards. Many were built along the Kent coast to defend Britain against the French in the early 1800s, then under the rule of Napoleon Bonaparte. Given that the Romney Marsh beaches are just 29 miles away from the French Coast across the English Channel, it was one of the areas that was most at risk from invasion by Napoleon's forces. Originally 103 towers were built in England between 1805 and 1812’. 74 were built along the Kent and Sussex coastlines from Folkestone to Seaford between 1805 and 1808, the other 29 to protect Essex and Suffolk. 45 of the towers still remain, but many are in ruins or have been converted, and only 9 remain in their (almost) original condition. Along the coastline of Romney Marsh, from Dymchurch Redoubt, south of Hythe, to St Mary's Bay, there were 9 Martello Towers built. Martello Towers Nos. 19, 20, 21, 22, 26 and 27 have since been demolished, but Towers Nos. 23, 24,and 25 still remain. Index Introduction……………………….. Page 2 Origins and Purpose…………….. Page 3 Design………………………..…… Page 4 Key Features…………………..…. Page 4 Artist’s Impression and Plans…… Page 5 Martello Tower No. 19………..….. Page 6 Martello Tower No. 20………..….. Page 7 Martello Tower No. 21………..….. Page 7 Martello Tower No. 22……..…….. Page 7 Martello Tower No. 23……..…….. Page 8 Martello Tower No. 24……..…….. Page 9 Martello Tower No. 25……..……. -

Defence Infrastructure Organisation Contacts

THE MINISTRY OF DEFENCE CONSERVATION MAGAZINE Number 40 • 2011 Defending Development Recreating the Contemporary Operating Environment Satellite tracking gannets Bempton Cliffs, East Yorkshire Help for Heroes Tedworth House Conservation Group Editor Clare Backman Photography Competition Defence Infrastructure Organisation Designed by Aspire Defence Services Ltd Multi Media Centre Editorial Board John Oliver (Chairman) Pippa Morrison Ian Barnes Tony Moran Editorial Contact Defence Infrastructure Organisation Building 97A Land Warfare Centre Warminster Wiltshire BA12 0DJ Email: [email protected] Tel: 01985 222877 Cover image credit Winner of Conservation Group Photography Competition Melita dimidiata © Miles Hodgkiss Sanctuary is an annual publication about conservation of the natural and historic environment on the defence estate. It illustrates how the Ministry of Defence (MOD) is King penguin at Paloma Beach © Roy Smith undertaking its responsibility for stewardship of the estate in the UK This is the second year of the MOD window. This photograph has great and overseas through its policies Conservation Group photographic initial impact and a lovely image to take! and their subsequent competition and yet again we have had The image was captured by Hugh Clark implementation. It an excellent response with many from Pippingford Park Conservation is designed for a wide audience, wonderful and interesting photos. The Group. from the general public, to the Sanctuary board and independent judge, professional photographer David Kjaer Highly commended was the photograph people who work for us or (www.davidkjaer.com), had a difficult above of a king penguin at Paloma volunteer as members of the MOD choice but the overall winner was a beach, Falkland Islands, taken by Roy Conservation Groups. -

9. the Topography of the Walland Marsh Area Between the Eleventh and Thirteenth Centuries

9. The Topography of the Walland Marsh area between the Eleventh and Thirteenth Centuries Tim Tatton-Brown Introduction 27-9) in the Decalcified (Old) Marshland. In the centre Until the publication of the Soil Survey by Green (1968) of this latter area are the demesne lands around Agney most maps of the Romney and Walland Marsh area Court Lodge, which are documented in detail from the which attempted to reconstruct the topography of the early 13th century (the Court Lodge building was marsh before the great storms of the 13th century rebuilt in 1287'). In 1225 a large amount of stock is showed a large estuary or channel running from near recorded as having been taken to Agney (14 cows, one Appledore to curve south and east around the so-called bull, 100 sheep, and four horses to plough) and there can 'Archbishops' Innings' (Elliott 1862) south-west of the be no doubt that the area of Creek Ridge No. 2 was, by Rhee Wall, before turning north-east to run past Midley this date, fully reclaimed (Smith 1943, 147).Between the to a mouth near New Romney (Steers 1964; Ward demesne lands of the manor around the Court Lodge 1952,12). Since the Soil Survey was published most and the long strip of Upper and Lower Agney (which writers have assumed that the old main course of the was inned in and after the fourteenth century: Gardiner, Rother (or 'river of Newenden' as it appears to have 1988) is a roughly triangular area which is enclosed by been called in the thirteenth century) ran from sea walls (the still very massive wall from Baynham to Appledore to New Romney down the small meandering Hawthorn Corner is on its south side) and which stream shown just north of the Rhee Wall on Green's contains a very large creek relic on Green's soil map. -

The Waterloo Campaign, 15вЇ•Œ18 June, 1815 (The Sharpe

Sharpe’s Waterloo: The Waterloo Campaign, 15–18 June, 1815 (The Sharpe Series, Book 20), Bernard Cornwell, HarperCollins UK, 2009, 0007338767, 9780007338764, 448 pages. Lieutenant-Colonel Sharpe, sidelined on the Royal staff, magnificently siezes command at the final moment of the great victory. It is 1815. Sharpe is serving on the personal staff of the Prince of Orange, who refuses to listen to Sharpe’s reports of an enormous army, led by Napoleon, marching towards them. The Battle of Waterloo commences and it seems as if Sharpe must stand by and watch the grandest scale of military folly. But at the height of battle, as victory seems impossible, Sharpe takes command and the most hard-fought and bloody battle of his career becomes his most magnificent triumph. Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.. DOWNLOAD HERE Keeper of the Forest , Scott J. Patterson, May 1, 2007, , 228 pages. Somewhere in a small community located in the Rocky Mountains, John, a construction worker trying to make ends meet and provide a Christmas for his wife and children, is .... Sharpe's Trafalgar , Bernard Cornwell, Mar 17, 2009, Fiction, 320 pages. The year is 1805, and the Calliope, with Richard Sharpe aboard, is captured by a formidable French warship, the Revenant, which has been terrorizing British nautical traffic in ... -

![[Delete] Insert Title Page](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6281/delete-insert-title-page-2546281.webp)

[Delete] Insert Title Page

South East Strategic Regional Coastal Monitoring Programme BEACH MANAGEMENT PLAN REPORT Hythe Ranges 2010 BMP 118 June 2011 Beach Management Plan Site Report 2010 4cMU10 – Hythe Ranges Canterbury City Council Strategic Monitoring Military Road Canterbury Kent CT1 1YW Tel: 01227 862401 Fax: 01227 784013 e-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.se-coastalgroup.org.uk www.channelcoast.org Document Title: Beach Management Plan Site Report 2010 Reference: BMP 118 Status: Final Date: June 2011 Project Name: Strategic Regional Coastal Monitoring Management Units: 4c MU10 Author: M. Dorling Checked By A. Bear Approved By: J. Clarke Issue Revision Description Authorised 01 - Draft J. Clarke 02 01 Final Report J. Clarke i Beach Management Plan Site Report 2010 4cMU10 – Hythe Ranges Report Log MU11 This Unit MU09 Report Type (Dymchurch) (MU10) (Hythe) Annual Report 2004 Dover Harbour to Beachy Head – AR08 BMP 2005 BMP21 BMP29 BMP22 Annual Report 2006 Dover Harbour to Beachy Head – AR19 BMP 2006 BMP40 BMP41 BMP42 Annual Report 2007 Dover Harbour to Beachy Head – AR31 BMP 2007 BMP56 BMP57 BMP58 Annual Report 2008 Dover Harbour to Beachy Head – AR41 BMP 2008 BMP75 BMP76 BMP77 Annual Report 2009 Dover Harbour to Beachy Head – AR51 BMP 2009 BMP96 BMP97 BMP98 Annual Report 2010 Dover Harbour to Beachy Head – AR61 This Report BMP 2010 BMP117 BMP119 BMP118 ii Beach Management Plan Site Report 2010 4cMU10 – Hythe Ranges Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... -

Shorncliffe Redoubt, Sir John Moore Barracks, Shorncliffe, Folkestone, Kent Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results

Wessex Archaeology Shorncliffe Redoubt, Sir John Moore Barracks, Shorncliffe, Folkestone, Kent Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results Ref: 62501.01 November 2006 Shorncliffe Redoubt, Sir John Moore Barracks, Shorncliffe, Folkestone, Kent Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 62501.01 December 2006 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Shorncliffe Redoubt, Sir John Moore Barracks, Shorncliffe, Folkestone, Kent Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology..................................................1 1.3 Historical Background...............................................................................1 Introduction..................................................................................................1 The French Threat .......................................................................................2 The Napoleonic Wars and Evolution of the Rifle Regiment.........................3 After the Napoleonic Wars...........................................................................5