The Figure of Pierrot in Giraud, Ensor, Dowson and Beardsley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guy De Maupassant and the World of the Norman Peasant

MAUPASSANT AND THE NOlli~AN PEASk~T GUY DE YiliUPASSANT AND THE WORLD OF THE NORMAN PEASANT by ALAN HEAP, B.A., (HULL UNIVERSITY) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree .Master of Arts McMaster University November 1971 MASTER OF ARTS "(1971) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (Romance Languages) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: GUy de Maupassant and the World of the Norman Peasant AUTHOR: Alan Heap, B.A., Hull University SUPERVISOR: Dr. B. S. Pocknell NUMBER OF PAGES: iv, 188 SCOPE AND CONTENTS: The thesis examines in detail the nature of the contes paysans written by Maupassant and the literary techniques which made this section the most successful in his work. The paper indicates and explains Maupassant's particular affection for the Norman peasant, then examines the different aspects of the peasant's character and the role he plays in the stories. An analysis is also made of other features of the peasant tales, such as the language, the decor, and the social events, while illustrating throughout the literary function of these elements. In the Conclusion, a comparison with other writers serves to demonstrate the reasons for the particular success of the contes paysans. ii -:.' ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to Dr. B. S. Pocknell, whose constant guidance and attention both to the organisation and to the writing of this thesis were greatly appreciated. iii TAB LE o F CON TEN TS Page CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER II - CHARACTERISATION OF THE PEASANTS 39 CHAPTER III - THE DECOR AND ITS LITERARY VALUE 125 CHAPTER IV - CONCLUSION 157 BIBLIOGRAPHY 180 iv CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Most of the critical works on Maupassant's short stories refer at some point to the success of his portrayal of the Norman peasant and to the artistic merits of the peasant contes themselves. -

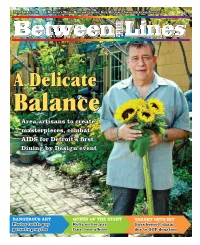

Area Artisans to Create Masterpieces, Combat AIDS for Detroit's First

PRIDESOURCE.COM MICHIGAN’S WEEKLY NEWS FOR LESBIANS, GAYS, BISEXUALS, TRANSGENDERS AND FRIENDS 1831 08.05.10 A Delicate Balance Area artisans to create masterpieces, combat AIDS for Detroit’s first Dining by Design event DANGEROUS ART QUEEN OF THE NIGHT TARGET GETS HIT Photos tackle gay Kelis on her gay Gays boycott chain parenting myths fans, new album due to GOP donation 2 Between The Lines • August 5, 2010 August 5, 2010 Vol. 1831 • Issue 673 Publishers Susan Horowitz Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi Associate News Editor Jessica Carreras Arts & Theater Editor 12 19 21 34 Donald V. Calamia Editorial Intern 13 NJ Supreme Court rejects 25 Curtain Calls Lucy Hough News same-sex marriage case Reviews of “The Last Night of Ballyhoo” and Contributing Writers Lawsuit filed over whether state’s civil union “Herstory Repeats Herself: A Trilogy in 3-D” Charles Alexander, Paul Berg, Wayne Besen, 5 Between Ourselves law provides equal treatment for gay couples D.A. Blackburn, Dave Brousseau, Tony O’Rourke-Quintana Michelle E. Brown, John Corvino, 26 Happenings Jack Fertig, Joan Hilty, Lisa Keen, Jim Larkin, Jason A. Michael, 14 International News Briefs Anthony Paull, Crystal Proxmire, 6 A Delicate Balance Gay weddings begin in Argentina Bob Roehr, Gregg Shapiro, Jody Valley, Beauty of art meets darkness of disease Rear View D’Anne Witkowski, Imani Williams at Detroit’s first Dining by Design HIV/AIDS Rex Wockner, Dan Woog fundraiser Opinions Contributing Photographer 28 Dear Jody Andrew -

Surviving Set Theory: a Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory

Surviving Set Theory: A Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Angela N. Ripley, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: David Clampitt, Advisor Anna Gawboy Johanna Devaney Copyright by Angela N. Ripley 2015 Abstract Undergraduate music students often experience a high learning curve when they first encounter pitch-class set theory, an analytical system very different from those they have studied previously. Students sometimes find the abstractions of integer notation and the mathematical orientation of set theory foreign or even frightening (Kleppinger 2010), and the dissonance of the atonal repertoire studied often engenders their resistance (Root 2010). Pedagogical games can help mitigate student resistance and trepidation. Table games like Bingo (Gillespie 2000) and Poker (Gingerich 1991) have been adapted to suit college-level classes in music theory. Familiar television shows provide another source of pedagogical games; for example, Berry (2008; 2015) adapts the show Survivor to frame a unit on theory fundamentals. However, none of these pedagogical games engage pitch- class set theory during a multi-week unit of study. In my dissertation, I adapt the show Survivor to frame a four-week unit on pitch- class set theory (introducing topics ranging from pitch-class sets to twelve-tone rows) during a sophomore-level theory course. As on the show, students of different achievement levels work together in small groups, or “tribes,” to complete worksheets called “challenges”; however, in an important modification to the structure of the show, no students are voted out of their tribes. -

Resistance Through 'Robber Talk'

Emily Zobel Marshall Leeds Beckett University [email protected] Resistance through ‘Robber Talk’: Storytelling Strategies and the Carnival Trickster The Midnight Robber is a quintessential Trinidadian carnival ‘badman.’ Dressed in a black sombrero adorned with skulls and coffin-shaped shoes, his long, eloquent speeches descend from the West African ‘griot’ (storyteller) tradition and detail the vengeance he will wreak on his oppressors. He exemplifies many of the practices that are central to Caribbean carnival culture - resistance to officialdom, linguistic innovation and the disruptive nature of play, parody and humour. Elements of the Midnight Robber’s dress and speech are directly descended from West African dress and oral traditions (Warner-Lewis, 1991, p.83). Like other tricksters of West African origin in the Americas, Anansi and Brer Rabbit, the Midnight Robber relies on his verbal agility to thwart officialdom and triumph over his adversaries. He is, as Rodger Abrahams identified, a Caribbean ‘Man of Words’, and deeply imbedded in Caribbean speech-making traditions (Abrahams, 1983). This article will examine the cultural trajectory of the Midnight Robber and then go on to explore his journey from oral to literary form in the twenty-first century, demonstrating how Jamaican author Nalo Hopkinson and Trinidadian Keith Jardim have drawn from his revolutionary energy to challenge authoritarian power through linguistic and literary skill. The parallels between the Midnight Robber and trickster figures Anansi and Brer Rabbit are numerous. Anansi is symbolic of the malleability and ambiguity of language and the roots of the tales can be traced back to the Asante of Ghana (Marshall, 2012). -

Bomb Threat Suspect Found

Researcher receives science El Gallo de Oro lacks CMU students perform at contribution award • A4 drastic changes • A6 FringeNYC • B8 SCITECH FORUM PILLBOX thetartan.org @thetartan August 27, 2012 Volume 107, Issue 2 Carnegie Mellon’s student newspaper since 1906 Bomb Hunt Library gets new layout Wheels on bus to threat keep going round MADELYN GLYMOUR membership ratified it by a News Editor 10-to-one margin, and the suspect reason they ratified it by that The Port Authority an- margin was because of that nounced last Tuesday that the language.” found service reduction planned for Palonis pointed to Allegh- Sept. 2 would be postponed eny County Executive Rich JUSTIN MCGOWN until at least August 2013. Fitzgerald as another pivotal Staffwriter The postponement is the player in the agreement. result of a deal reached by “He really kept our nose The FBI officially in- the Port Authority, Allegh- to the grindstone throughout dicted Adam Stuart Busby eny County, Governor Tom this process,” Palonis said. on Aug. 22 for sending over Corbett’s office, and the Lo- “Rich is an advocate for trans- 40 threatening emails to the cal 85 Amalgamated Transit portation. I’ve dealt with a lot University of Pittsburgh last Union. Under the deal, Port of politicians through this year. Busby’s emails were Authority employees in the process, but Rich really wants part of a series of over 100 Local 85 union will undergo to see transportation grow.” bomb threats issued to Pitt a two-year pay freeze and According to the Pitts- throughout the spring se- increase the percentage of burgh Post-Gazette, Fitzger- mester. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

Download This Issue

volume 4 issue 6 2011 P11238-VANDY-TourGuides:Layout 1 2/17/11 4:21 PM Page 1 Value is the new luxury.™ Fortunately we deliver both in 2010 EAST COAST TOP DOG ENTERTAINMENT HOTEL HARMONIOUS SERVICES. CHART-TOPPING LOCATION. LIVE ENTERTAINMENT NIGHTLY. FRESH FARM-TO-TABLE CUISINE AT EAT. STEAK PERFECTION AT RUTH’S CHRIS. loewshotels.com 800.23.LOEWS mobile production monthly 1 con volume 4 issue 6 2011 tents 12 14 mobilePRODUCTIONmonthly 6 In the News 18 Josh Groban 6 Catering Eat To The Beat Looking Forward to a Great Summer! Straight To You Tour 2011 Shrinks Arenas to the Size of a Theater 6 Hardware Penn Guard Now Available in Smaller Packages 7 Rigging Sapsis Rigging provides rigging package for third annual 22 Tour Vendors Castleton Festival 26 Crew Members 7 Sound L-ACOUSTICS Sells First KARA System to Slovenia / Rat Sound Packs Rodent-Sized L-ACOUSTICS KIVA-KILO System 28 Five Points 7 Staging Precise Corporate Staging Expands L-ACOUSTICS How Many Points Does it Take to Rig a Show? inventory for Summer Festival Season Just Five Points! 8 Transportation Air Charter Service Continues Global Expansion / Beat The Street Lauches New Ground Transport Venture 30 Maryland Sound Inc. 8 Video PRG Acquires Nocturne Productions / Gray Matter Enter- A Stealthy Company WIth a Big Fat Sound tainment Delivers Video Design for Nicki Minaj's Live Tour With Britney Spears 32 Knifedge 9 Why Didn't I Think Of That? Towels For The Road, On The Road At the Cutting Edge of Content Creation Upstaging John Huddleston 12 Video Battlecruiser 32 Backs Up the Best Issues a Call to a Higher Standard of Safety 36 S.O.R.D. -

Pierrot Lunaire Translation

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Pierrot Lunaire, Op.21 (1912) Poems in French by Albert Giraud (1860–1929) German text by Otto Erich Hartleben (1864-1905) English translation of the French by Brian Cohen Mondestrunken Ivresse de Lune Moondrunk Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder, A flots verts de la Lune coule, Flows nightly from the Moon in torrents, Und eine Springflut überschwemmt Et submerge comme une houle And as the tide overflows Den stillen Horizont. Les horizons silencieux. The quiet distant land. Gelüste schauerlich und süß, De doux conseils pernicieux In sweet and terrible words Durchschwimmen ohne Zahl die Fluten! Dans le philtre yagent en foule: This potent liquor floods: Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt, Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux The wine we drink with our eyes Gießt Nachts der Mond in Wogen nieder. A flots verts de la Lune coule. Flows from the moon in raw torrents. Der Dichter, den die Andacht treibt, Le Poète religieux The poet, ecstatic, Berauscht sich an dem heilgen Tranke, De l'étrange absinthe se soûle, Reeling from this strange drink, Gen Himmel wendet er verzückt Aspirant, - jusqu'à ce qu'il roule, Lifts up his entranced, Das Haupt und taumelnd saugt und schlürit er Le geste fou, la tête aux cieux,— Head to the sky, and drains,— Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt. Le vin que l'on boit par les yeux! The wine we drink with our eyes! Columbine A Colombine Colombine Des Mondlichts bleiche Bluten, Les fleurs -

Costume Crafts an Exploration Through Production Experience Michelle L

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Costume crafts an exploration through production experience Michelle L. Hathaway Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hathaway, Michelle L., "Costume crafts na exploration through production experience" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2152. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COSTUME CRAFTS AN EXPLORATION THROUGH PRODUCTION EXPERIENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The Department of Theatre by Michelle L. Hathaway B.A., University of Colorado at Denver, 1993 May 2010 Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my family for their constant unfailing support. In particular Brinna and Audrey, girls you inspire me to greatness everyday. Great thanks to my sister Audrey Hathaway-Czapp for her personal sacrifice in both time and energy to not only help me get through the MFA program but also for her fabulous photographic skills, which are included in this thesis. I offer a huge thank you to my Mom for her support and love. -

Layering Stories and Scripture by Craig Giera Date

A Visual Exegesis for Preaching: Layering Stories and Scripture by Craig Giera Date: ___4/26/2019___ Approved: _____ ____ Jerusha Neal, Supervisor ______________________________________ Luke Powery, Second Reader _____ __ William Willimon, D. Min. Director Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in the Divinity School of Duke University 2019 A Visual Exegesis for Preaching: Layering Stories and Scripture by Craig Giera Date: ___4/26/2019____ Approved: _____ ____ Jerusha Neal, Supervisor ______________________________________ Luke Powery, Second Reader _____ __ William Willimon, D. Min. Director An abstract of a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Ministry in the Divinity School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Craig Giera 2019 Abstract This thesis will describe the way a story functions within a sermon as a layer of meaning placed over the biblical text that enhances a particular message from the Gospel. Stories allow the faithful to become active listeners as they unite their own stories to the one being told, creating a shared, lived experience. To demonstrate how the layering of stories function in a homily, I have created an art series of assemblages, visually illustrating how each layer focuses on certain textual details while discarding others. This visual exegesis highlights themes in the biblical text and illuminates the sermonic role of stories. It also provides an avenue for spiritual reflection, revealing similarities between my artistic process and my process of sermon preparation. The thesis is completed with a homily, synthesizing the elements described and sharing a message of hope from the scriptural account of the three young men in the fiery furnace (Daniel 3). -

Broadway Costumes 2012 Rental List

Broadway Costumes Costume Rentals How-To’s, Contract Terms & Conditions Rental Rates & Deposits: The basic rental period is 2 nights. We do not charge for any days that Broadway Costumes is closed. Additional days rent at the rate of 20% per day plus tax. Special weekly rates and “play” rates may apply. Just inquire as to your special needs. Deposits are required and are usually twice the amount required as the stated rental rate up to and including the current retail value. Minimum deposit is $20. Deposits are not refundable for any cancellations unless 1 (one) week or more in advance, then 50% refunded. The deposit is NOT part of the rental balance. The entire rental balance is due when the costume is picked up. Deposits may be made by credit card (Visa, MasterCard, American Express) or by cash. Deposits are refunded after costume return and any applicable fees are paid. Rental Return: You must return all rented items by the date stated on the contract. Items not returned on the specified date are subject to a late fee of 20% of the basic rental rate per day late plus tax. Alterations by Broadway Costumes: Alterations and cleaning are normally included in the rental price. However, alterations may take up to two weeks at peak seasons; faster service may require an additional service charge. Alterations by Customer: NO ALTERATIONS are allowed by the customer. Any alterations done outside of Broadway Costumes will be considered as damage and will result in assessed fees. Smoking and Eating While in Costume: Be very cautious. -

Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Clown: Narrative Structure and Purpose in Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire Mike Fabio Introduction In September of 1912, a 37-year-old Arnold Schoenberg sat in a Berlin concert hall awaiting the premier of his 21st opus, Pierrot Lunaire. A frail man, as rash in his temperament as he was docile when listening to his music, Schoenberg watched as the lights dimmed and a fully costumed Pierrot took to the stage, a spotlight illuminating him against a semitransparent black screen through which a small instrumental ensemble could be seen. But as Pierrot began singing, the audience quickly grew uneasy, noting that Pierrot was in fact a woman singing in the most awkward of styles against a backdrop of pointillist atonal brilliance. Certainly this was not Beethoven. In a review of the concert, music critic James Huneker wrote: The very ecstasy of the hideous!…Schoenberg is…the cruelest of all composers, for he mingles with his music sharp daggers at white heat, with which he pares away tiny slices of his victim’s flesh. Anon he twists the knife in the fresh wound and you receive another thrill…. There is no melodic or harmonic line, only a series of points, dots, dashes or phrases that sob and scream, despair, explode, exalt and blaspheme.1 Schoenberg was no stranger to criticism of this nature. He had grown increasingly contemptuous of critics, many of whom dismissed his music outright, even in his early years. When Schoenberg entered his atonal period after 1908, the criticism became far more outrageous, and audiences were noted to have rioted and left the theater in the middle of pieces.