1113384 [2012] RRTA 951 (30 November 2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy and Religious Pluralism in Southeast Asia: Indonesia and Malaysia Compared

Key Issues in Religion and World Affairs Democracy and Religious Pluralism in Southeast Asia: Indonesia and Malaysia Compared Kikue Hamayotsu Department of Political Science, Northern Illinois University September, 2015 Introduction Dr. Hamayotsu is Associate Professor of Political It is an intuitive expectation that democracy will accompany – and Science. Dr. Hamayotsu reinforce – pluralistic attitudes and mutual respect for all members has conducted research on of a society, regardless of their sub-national, ethnic, and religious state-society relations in identity and affiliation. The noted political scientist Alfred Stepan, for both Malaysia and example, propounds the concept of “twin tolerations” – that is, Indonesia and her current mutual respect between and within state and religious institutions – research projects include in fostering a modern liberal democracy. According to this thesis, religious movements and two specific conditions have to be met in order to guarantee open parties, shariʽa politics, competition over values, views, and goals that citizens want to religious conflict, and the advance. One is toleration of religious citizens and communities quality of democracy. Her towards the state, and the other is toleration of the state authorities research and teaching towards religious citizens and communities (Stepan 2007). interest include: However, such conditions are not readily fulfilled in deeply divided societies. Southeast Asian nations are well known for being “plural Comparative Politics, societies” with a high degree of ethnic and religious heterogeneity Religion and Politics, (Furnivall 1944). For various regimes and ruling elites in those Political Islam, nations, the accommodation of various collective identities to build Democratization, Social a common national identity, modern nationhood, and citizenry has Movements, and Ethnic not always been easy or peaceful. -

Bpalive2012 Compile Web.Pdf

2012 Disclaimer No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any or other means, including electronic, mechanical or photocopying or in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of BP Healthcare Group. About a year ago(2003), I was diagnosed with cancer. I had a scan at 7:30 in “the morning, and it clearly showed a tumour on my pancreas. I didn't even know what a pancreas was. All the doctors told me was that this was almost certainly a type of cancer that is incurable, and that I should expect to live no longer than three to six months." Later that evening, I had a biopsy, where they inserted an endoscope down “my throat, through my stomach and into my intestines, put a needle into my pancreas and removed a few cells from the tumour. I was sedated, but my wife, who was there, told me that when they viewed the cells under a microscope the doctors started crying because it turned out to be a very rare form of pancreatic cancer that is curable with surgery. I had the surgery and I'm fine now." If it wasn't for the wonders of health screening, diagnosis and treatment, Jobs would not be able to introduce iPhone 3G on June 9, 2008, new iPod media players on Sept 9, 2008, and unveil a lighter MacBook Air laptop on Oct 20, 2010 Source: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2005/june15/jobs-061505.html http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-01-17/steve-jobs-s-health- reports-since-his-cancer-diagnosis-in-2003-timeline.html Steve Jobs 1955-2011 Contents History 1-2 Corporate Structure 3 Board Of Directors -

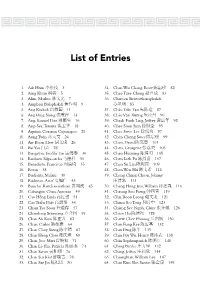

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Ewa Journal Ok

CONTENTS East West Affairs | Volume 2 Number 1 | January-March 2014 Editorial 5. Postnormal Governance | Jordi Serra Commentaries 13. Iran’s “Charm Offensive” | Stephenie Wright 21. A Very African Homosexuality | Zain Sardar 29. Malaysian Shadow Play | Merryl Wyn davieS Papers 35. Come together...for what? Creativity and Leadership in Postnormal Times | alfonSo Montuori and gabrielle donnelly 53. The Story of a Phenomenon: Vivekananda in Nirvana Land | vinay lal 69. The Pedagogical Subject of Neoliberal Development | alvin Cheng -h in liM 93. Science Fiction Futures and the Extended Present of 3D Printers | JoShua pryor 109. Muslim Superheroes | gino Zarrinfar 123. The Joys of Being Third Class | Shiv viSanathan Review 165. How the East was Won | Shanon Shah Report 165. Looking in All Directions | John a. S Weeney East-West Affairs 1 East West Affairs a Quarterly journal of north-South relations in postnormal times EDITOrS Ziauddin Sardar, Centre for policy and futures Studies, east-West university, Chicago, uSa Jerome r. ravetz, research Methods Consultancy, oxford, england DEPuTy EDITOrS Zain Sardar, birkbeck College, university of london, england Gordon Blaine Steffey, department of religious Studies, randolph College, lynchburg, uSa John A. Sweeney, department of political Science, university of hawaii at Manoa, honolulu, uSa MANAGING EDITOr Zafar A. Malik, dean for development and university relations, east-West university, Chicago, uSa DEPuTy MANAGING EDITOr Joel Inwood, development and university relations, east-West university, -

Malaysia: the 2020 Putsch for Malay Islam Supremacy James Chin School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania

Malaysia: the 2020 putsch for Malay Islam supremacy James Chin School of Social Sciences, University of Tasmania ABSTRACT Many people were surprised by the sudden fall of Mahathir Mohamad and the Pakatan Harapan (PH) government on 21 February 2020, barely two years after winning the historic May 2018 general elections. This article argues that the fall was largely due to the following factors: the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu Islam (Malay Islam Supremacy); the Mahathir-Anwar dispute; Mahathir’s own role in trying to reduce the role of the non-Malays in the government; and the manufactured fear among the Malay polity that the Malays and Islam were under threat. It concludes that the majority of the Malay population, and the Malay establishment, are not ready to share political power with the non- Malays. Introduction Many people were shocked when the Barisan National (BN or National Front) govern- ment lost its majority in the May 2018 general elections. After all, BN had been in power since independence in 1957 and the Federation of Malaysia was generally regarded as a stable, one-party regime. What was even more remarkable was that the person responsible for Malaysia’s first regime change, Mahathir Mohammad, was also Malaysia’s erstwhile longest serving prime minister. He had headed the BN from 1981 to 2003 and was widely regarded as Malaysia’s strongman. In 2017, he assumed leader- ship of the then-opposition Pakatan Harapan (PH or Alliance of Hope) coalition and led the coalition to victory on 9 May 2018. He is remarkable as well for the fact that he became, at the age of 93, the world’s oldest elected leader.1 The was great hope that Malaysia would join the global club of democracy but less than two years on, the PH government fell apart on 21 February 2020. -

1930 1435218997 G1511786.Pdf

United Nations A/HRC/29/NGO/87 General Assembly Distr.: General 9 June 2015 English only Human Rights Council Twenty-ninth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by the Aliran Kesedaran Negara National Consciousness Movement, non- governmental organization on the roster The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [25 May 2015] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non-governmental organization(s). GE.15-09265 (E) A/HRC/29/NGO/87 Crackdown on freedom of expression and assembly in Malaysia There has been a serious regression in Malaysia's democratic space in 2015, with the government's crackdown on freedom of speech and assembly, predominantly through the use of the Sedition Act 1948, Peaceful Assembly Act 2012, and various sections of the Penal Code. Freedom of speech and expression is enshrined in Article 10(1)(a) of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia. However, the guarantee of such a right is severely limited and qualified by broad provisions in Article 10(2)(a), which stipulates that Parliament may impose “such restrictions as it deems necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of the Federation or any part thereof”. Similarly, the freedom of assembly is enshrined in Article 10(1)(b) of the Constitution, but is restricted through Article 10(2), 10(4) and Article 149 of the Constitution. -

Interrogating National Identity Ethnicity, Language and History in K.S

Dashini Jeyathurai Interrogating National Identity Ethnicity, Language and History in K.S. Maniam's The Return and Shirley Geok-lin Lim's Joss and Gold DASHINI JEYATHURAI University of Michigan at Ann Arbor AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Dashini Jeyathurai is from Malaysia and received a B.A. in English from Carleton College in Minnesota. Jeyathurai is a first year student in the Joint Ph.D. for English and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. Introduction organization believes that the Malay ethnic majority are In this paper, I examine how two Malaysian authors, the rightful citizens of Malaysia and deserve to be given ethnically Chinese Shirley Geok-lin Lim and ethnically special political, economic and educational privileges. Indian K.S. Maniam, challenge the Malay identity that Then Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, a Malay the government has crafted and presented as the himself, created this concept as well as the practice of national identity for all Malaysians. In their novels in giving special privileges to Malays. He also coined the English Joss & Gold (2001) and The Return (1981) term bumiputera (sons/princes of the soil) to refer to respectively, Lim and Maniam interrogate this Malays. Both the term and practice came into official construct through the lenses of ethnicity, history and use in 1965 and are still in existence today. Two years language. In critiquing the government’s troubling later, the predominantly Malay government established construction of a monoethnic and monolingual Malay as the national language of the country. In 1970, national identity, Lim and Maniam present both the the government made Islam the state religion. -

Peny Ata Rasmi Parlimen

Jilid 1 Harl Khamis Bil. 68 15hb Oktober, 1987 MAL AYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT House of Representatives P ARLIMEN KETUJUH Seventh Parliament PENGGAL PERTAMA First Session KANDUNGANNYA JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 11433] USUL-USUL: Akta Acara Kewangan 1957- Menambah Butiran Baru "Kumpulan Wang Amanah Pembangunan Ekonomi Belia", dan "Tabung Amanah Taman Laut dan Rezab Laut" [Ruangan 11481] Akta Persatuan Pembangunan Antarabangsa 1960-Caruman Malaysia [Ruangan 11489] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Kumpulan Wang Amanah Negara [Ruangan 11492] Dl(;ETA� OLEH JABATAN P1UlC£TAJtAN NEGARA. KUALA LUMPUR HA.JI MOKHTAR SMAMSUDDlN.1.$.D., S,M,T., $,M.S., S.M.f'., X.M.N., P.l.S., KETUA PS.NOAK.AH 1988 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KETUJUH Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG PERTAMA AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAJI ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri dan Menteri Kehakiman, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, s.s.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., s.P.C.M., s.s.M.T., D.U.N.M., P.1.s. (Kubang Pasu). Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Pembangunan Negara " dan Luar Bandar, TUAN ABDUL GHAFAR BIN BABA, (Jasin). Yang Berhormat Menteri Pengangkutan, DATO DR LING LIONG SIK, D.P.M.P. (Labis). Menteri Kerjaraya, DATO' S. -

(Company No: 50948-T) Incorporated in Malaysia CONTENTS

(Company No: 50948-T) Incorporated in Malaysia CONTENTS METRO KAJANG HOLDINGS BERHAD 2 • Notice of Annual General Meeting (Company No.50948-T • Incorporated in Malaysia) 4 • Statement on Particulars of Directors 7 • Corporate Information 8 • Chairman’s Statement 10 • Director’s Profile 13 • Corporate Governance 20 • Audit Committee 24 • Directors’ Report 30 • Statement by Directors 30 • Statutory Declaration 31 • Report of the Auditors to the Members 32 • Balance Sheets 34 • Income Statements 35 • Statements of Changes in Equity 37 • Cash Flow Statements 39 • Notes to the Financial Statements 74 • List of Properties 78 • Statistics of Shareholdings Form of Proxy METRO KAJANG HOLDINGS BERHAD (Company No.50948-T • Incorporated in Malaysia) Notice of Annual General Meeting NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT the Twenty-Second Annual General Meeting of METRO KAJANG HOLDINGS BERHAD will be held at Ballroom, First Floor, Metro Inn, Jalan Semenyih, 43000 Kajang, Selangor Darul Ehsan on Wednesday, 30 January 2002 at 10.00 a.m. to transact the following business: ORDINARY BUSINESS: 1. To receive the Audited Accounts for the year ended 30 September 2001 together with the Directors’ and Auditors’ reports thereon. (ORDINARY RESOLUTION 1) 2. To approve the payment of a First and Final Tax Exempt dividend of 3.5% per share for the year ended 30 September 2001. (ORDINARY RESOLUTION 2) 3. To approve Directors’ fees amounting to RM32,000-00 for the year ended 30 September 2001. (ORDINARY RESOLUTION 3) 4. To re-elect the following Directors who retire in accordance with the Company’s Articles of Association and being eligible, offer themselves for re-election. -

Who's There? Program

July 24-Aug 15 Created by The Transit Ensemble Singapore | Malaysia | United States August 4-8, 2020 ABOUT THE SHOW WHO'S THERE? Created by The Transit Ensemble Presented by New Ohio Theatre August 4th - 8th on Zoom Part of Ice Factory 2020 A Black American influencer accuses a Malaysian bureaucrat of condoning blackface. A Singaporean-Indian teacher launches an Instagram feud calling out racial inequality at home, post-George Floyd. A privileged Singaporean-Chinese activist meets a compassionate White Saviour, and an ethnically ambiguous political YouTuber takes a DNA test for the first time. A cross-cultural encounter involving artists based in Singapore, Malaysia, and the United States, Who’s There? uses Zoom as a new medium to explore the unstable ground between us and “the other”. In this pandemic contact zone, lines along race, class and gender bleed into one another, questioning the assumptions we hold of ourselves and the world around us. What sort of tensions, anxieties and possibilities emerge, and how can we work to reimagine a New Normal? To receive updates on future iterations of the show, join our mailing list here. COLLABORATORS Co-Directed by Sim Yan Ying "YY" & Alvin Tan Featuring: Camille Thomas - Performer 1, Iyla Rotum, Cops (interview) Ghafir Akbar - Performer 2, Amir Hamzah, Angela Davis (interview) Neil Redfield - Performer 3, Adam Noble, Karen (video) Rebekah Sangeetha Dorai ெரெபகா ச¥Àதா ெடாைர - Performer 4, Sharmila Thodak, K. Shivendra (interview) Sean Devare - Performer 5, Jordan Grey Sim Yan Ying “YY” - Performer 6, Chan Yue Ting "YT" Dramaturgy by Cheng Nien Yuan & J.Ed Araiza Multimedia Design by Jevon Chandra Sound Design by Jay Ong Publicity Design by Sean Devare Stage Manager - Manuela Romero Stage Management Intern - Priyanka Kedia Marketing & Multimedia Intern - Ryan Henry With interviews from S Rahman Liton & Janelyn, edited for length CO-DIRECTOR'S NOTE Sim Yan Ying "YY", Co-Director Just two months ago, Who’s There? was only a seed of an idea. -

Sacred Cows and Crashing Boars : Ethno-Religious

This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Critical Asian Studies, Volume 44, Issue 1, pp. 31-56, available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/14672715.2012.644886 SACRED COWS AND CRASHING BOARS Ethno-Religious Minorities and the Politics of Online Representation in Malaysia Susan Leong ABSTRACT: Starting with the incident now known as the cow’s head protest, this article traces and unpacks the events, techniques, and conditions surrounding the representation of ethno-religious minorities in Malaysia. The author suggests that the Malaysian Indians’ struggle to correct the dominant reading of their community as an impoverished and humbled underclass is a disruption of the dominant cul- tural order in Malaysia. The struggle is also among the key events to have set in motion a set of dynamics—the visual turn—introduced by new media into the poli- tics of ethno-communal representation in Malaysia. Believing that this situation requires urgent examination the author attempts to outline the problematics of the task. What first undermines and then kills political communities is loss of power and final impotence.… Power is actualized only where word and deed have not parted company, where words are not empty and deeds not brutal, where words are not used to veil intentions but to disclose reali- ties, and deeds are not used to violate and destroy but to establish rela- 1 tions and create new realities. — Hannah Arendt, 1958 On 28 August 2009 fifty men lugged a severed cow’s head to the gates of the State Secretariat building in the city of Shah Alam, Malaysia. -

Malaysia's Brief, Rich History of Suspending Newspapers the Malaysian Insider July 27, 2015 by Anisah Shukry

Malaysia’s brief, rich history of suspending newspapers The Malaysian Insider July 27, 2015 By Anisah Shukry The Edge Weekly and The Edge Financial Daily's three-month suspension starting today marks the government's continued tradition of clamping down on print media, a practice which began nearly three decades ago with the infamous Ops Lalang of 1987. The Edge joins The Star, The Sunday Star, Sin Chew Jit Poh, Watan, Sarawak Tribune, Guang Ming Daily, Berita Petang Sarawak, The Weekend Mail, Makkal Ossai, The Heat and Thina Kural, which had their publishing permits revoked for reasons ranging from national security to technical issues. Most papers survived their suspension, even as it dragged on for months, with journalists reportedly taking up part-time jobs to support their families until the newsrooms reopened. But some newspapers never recovered, while others never saw their suspensions lifted. The Edge, however, which is being punished for its reportage on debt-ridden state investment firm 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), is fighting this. This morning, The Edge will file a leave application for a judicial review. Speaking to reporters after briefing The Edge's staff, hours after the suspensions were announced on Friday, The Edge Media Group publisher and group CEO Ho Kay Tat said: "We will be filing it on Monday and we hope to get a speedy hearing." "We must file a judicial review as a matter of principle because we don't think the suspension is justified," he said. Ho also said The Edge would continue reporting on 1MDB through its online platforms despite the suspension of the two papers.