Social Action in Three Norwich Estates, 1940-2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for North Central London Joint Health

Agenda Public Document Pack NORTH CENTRAL LONDON JOINT HEALTH OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE FRIDAY, 31 JANUARY 2020 AT 10.00 AM COUNCIL CHAMBER, HARINGEY CIVIC CENTRE, HIGH ROAD, LONDON N22 8LE Enquiries to: Sola Odusina, Committee Services E-Mail: [email protected] Telephone: 020 7974 6884 (Text phone prefix 18001) Fax No: 020 7974 5921 MEMBERS Councillor Alison Kelly (London Borough of Camden) (Chair) Councillor Tricia Clarke, London Borough of Islington (Vice-Chair) Councillor Pippa Connor, London Borough of Haringey (Vice-Chair) Councillor Sinan Boztas, London Borough of Enfield Councillor Alison Cornelius, London Borough of Barnet Councillor Lucia das Neves, London Borough of Haringey Councillor Clare De Silva, London Borough of Enfield Councillor Linda Freedman, London Borough of Barnet Councillor Osh Gantly, London Borough of Islington Councillor Samata Khatoon, London Borough of Camden Issued on: Thursday, 23 January 2020 This page is intentionally left blank NORTH CENTRAL LONDON JOINT HEALTH OVERVIEW AND SCRUTINY COMMITTEE 31 JANUARY 2020 THERE ARE NO PRIVATE REPORTS PLEASE NOTE THAT PART OF THIS MEETING MAY NOT BE OPEN TO THE PUBLIC AND PRESS BECAUSE IT MAY INVOLVE THE CONSIDERATION OF EXEMPT INFORMATION WITHIN THE MEANING OF SCHEDULE 12A TO THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT 1972, OR CONFIDENTIAL WITHIN THE MEANING OF SECTION 100(A)(2) OF THE ACT. ANNOUNCEMENT Webcasting of the Meeting The Chair to announce the following: Please note that this meeting may be filmed or recorded by the Council for live or subsequent broadcast via the Council’s internet site or by anyone attending the meeting using any communication method. Although we ask members of the public recording, filming or reporting on the meeting not to include the public seating areas, members of the public attending the meeting should be aware that we cannot guarantee that they will not be filmed or recorded by others attending the meeting. -

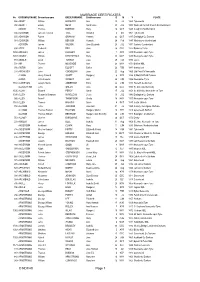

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON -

Forgotten Heritage: the Landscape History of the Norwich Suburbs

Forgotten Heritage: the landscape history of the Norwich suburbs A pilot study. Rik Hoggett and Tom Williamson, Landscape Group, School of History, University of East Anglia, Norwich. This project was commissioned by the Norwich Heritage, Economic and Regeneration Trust and supported by the East of England Development Agency 1 Introduction Over recent decades, English Heritage and other government bodies have become increasingly concerned with the cultural and historical importance of the ordinary, ‘everyday’ landscape. There has been a growing awareness that the pattern of fields, roads and settlements is as much a part of our heritage as particular archaeological sites, such as ancient barrows or medieval abbeys. The urban landscape of places like Norwich has also begun to be considered as a whole, rather than as a collection of individual buildings, by planning authorities and others. However, little attention has been afforded in such approaches to the kinds of normal, suburban landscapes in which the majority of the British population actually live, areas which remained as countryside until the end of the nineteenth century but which were then progressively built over. For most people, ‘History’ resides in the countryside, or in our ancient towns and cities, not in the streets of suburbia. The landscape history of these ordinary places deserves more attention. Even relatively recent housing developments have a history – are important social documents. But in addition, these developments were not imposed on a blank slate, but on a rural landscape which was in some respects preserved and fossilised by urbanisation: woods, hedges and trees were often retained in some numbers, and their disposition in many cases influenced the layout of the new roads and boundaries; while earlier buildings from the agricultural landscape usually survived. -

Census, Sunday April 7Th 1861, Searching in Norfolk and Suffolk for Wherrymen

Census, Sunday April 7th 1861, searching in Norfolk and Suffolk for wherrymen. Please read before starting Abbreviations ag lab = agricultural labourer app = apprentice b-i-l + brother-in-law bn = born in dau = daughter emp = employing f-i-l = father-in-law gdau = granddaughter gdma = grandmother gdson = grandson gen = general GY = Great Yarmouth husb = husband ind = independent means jmn = journeyman lab = labourer mar = married m-i-l = mother-in-law Nch = Norwich NK = not known qv = which see S = Suffolk sch = at school servt = servant s-i-l = sister-in-law sp- = step- Su = Suffolk unk = unknown unm = unmarried ? = some doubt here (35) = age for disambiguation [ ] = editorial comment or correction { } = as information appears in the digitised index thegenealogist.co.uk * = note at end of Table General Many wherries on census night could have been on passage or moored well away from the routes of enumerators as they also could have been when each Household's form was distributed in the days prior to census night and collected afterwards. Wherry names are rarely recorded. Answers (rare) to the question 'Whether blind or deaf and dumb' are included in the 'Comments' column below. Only 15 'wherrymen' were noted in Norfolk and one in Suffolk. I have not distinguished between the descriptions 'waterman' and 'water man' etc. Occupations Robert Simper says, in Norfolk Rivers and Harbours (1996), 'In recent times the crew of a wherry have been called skipper and mate, but the old practice was to call them wherryman and waterman.' From my research I would say that 'waterman' could include both skipper and mate. -

Henderson Herald Is Produced by the Henderson Trust for the the Children Who Are Signed up for Term

light of the wide ranging Young changes to the benefit system.” Adult Ricky Buckland (18) a young adult carer is Carers Get thrilled about the support Henderson he and other carers will receive. “So many more Help They people will benefit from this service. The support Deserve. will be there as and when Carers who are aged 16 to you need it, as well as HERALD advice on things like sexual 24 and who look after a long-term sick or disabled health, benefits, jobs, Free Summer 2013 family member in the college, housing and much Henderson Trust area can more. It will give you that get free support and advice little break from home by from a new project funded meeting for a one-to-one Volunteers Sam And Remi NEWS by the Big Lottery. outside of your home, Because of their caring school or college – that’s FLASH role many young adult the great thing about this carers miss out on the project, it is centered same work, educational around the individual Protecting Your and social opportunities as young person.’ Child Against their friends. In addition The carers support for the majority of carers local people is part of a Measles report that the care they three-year project which There have been a number provide harms their own was launched earlier this of measles cases in physical health and stress year. If you are or know a England with some local levels. young person (16-24) outbreaks. John Lee, who is the providing care for a family Project Manager said; “At member you can help them Measles can cause very the moment, very few access free additional serious illness and is one carers are getting the help support and advice by of the most infectious and support that they are contacting: diseases known. -

The Norfolk Ancestor, the Journal of the NFHS 223 December 2010 CONTENTS Dec 2010 Page

The Christmas lights, Magdalen Street, Norwich, 1963, prior to building the flyover and Anglia Square. Norwich, 1963, prior to building the flyover and Magdalen Street, Christmas lights, Image shown with permission of Norfolk County Council Library and Information Service Norfolk Ancestor Volume Seven Part Four DECEMBER 2010 The Journal of the Norfolk Family History Society formerly Norfolk & Norwich Genealogical Society The Trustees and Volunteers of the Norfolk Family History Society wish a Merry Christmas and Prosperous New Year to all our Members More unknown photographs, see page 226 More unknown photographs, see page NORFOLK FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY A private company limited by guarantee Registered in England, Company No. 3194731 Registered as a Charity - Registration No. 1055410 Registered Office address: Kirby Hall, 70 St. Giles Street, _____________________________________________________________ HEADQUARTERS and LIBRARY Kirby Hall, 70 St Giles Street, Norwich NR2 1LS Tel: (01603) 763718 Email address: [email protected] NFHS Web pages:<http://www.norfolkfhs.org.uk BOARD OF TRUSTEES (for a full list of contacts please see page 250) Mike Dack (NORS Admin) Denagh Hacon (Editor, Ancestor) Paul Harman (Transcripts Organiser) Brenda Leedell (West Norfolk Group) Mary Mitchell (Monumental Inscriptions) Margaret Murgatroyd (Parish Registers) Edmund Perry (Company Secretary) Colin Skipper (Chairman) Jean Stangroom (Membership Secretary) Carole Taylor (Treasurer) Patricia Wills-Jones (East Norfolk Group) EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Denagh Hacon (Editor) -

'Othe Physiological Society Magazine

ISSN 1465-1483 Ae \e 'OThe Physiological Society Magazine Oxford Meeting Features on: Science Week Sodium channels in nociceptiveneurones Musicians &physiologists The Marae of New Zealand The Institute for Learning and Teaching Spring 2001 No 42 Students working in a FirstYear Physiologists Professor Clive Ellory,Head of Department PracticalClass The new NMR facility Artist's impressionof the new building extension for ProfessorFrancesAshcrofi and ProfessorKay Davies Frontcover: FranAshcroft's collaboratiomwith artistBenedict Rubbra depictingInsulin-Secretion Oxford Meeting Welcome to Oxford Clive Ellory ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Na tio na l Sc ie n c e We e k ........................................................................................................................ 4 Features The Politics of Animal Experimentation - The RDS Annual General Meeting Maggie Leggett .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Sodium Channels in Nociceptive Neurones Jim Elliott .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Musicians & Physiologists E. Geoffrey Walsh ............................................................................................................................................. -

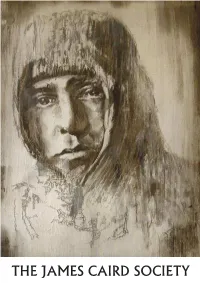

JCS Journal No. 9

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Nine Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton May 2018 1 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Nine Welcome, once more, to the latest JCS Journal (‘Number Nine’). Having succeeded Dr Jan Piggott as editor, I published my first Journal in April 2007 (‘Number Three’). As I write this introduction, therefore, I celebrate ten years in the ‘job’. Unquestionably it has been (and is) a lot of hard work but this effort is far outweighed by the excitement of being able to disseminate new insights and research on our favourite polar man. I have been helped, along the way, by many talented and willing authors, academics and enthusiasts. In the main, the material proffered over the years has been of such a high standard it convinced me to publish the The Shackleton Centenary Book (2014), Sutherland House Publishing, ISBN 978- 0-9576293-0-1, in January 2014 – cherry-picking the best articles and essays. This Limited Edition was fully-subscribed and, if I may say so, a great success. I believe the JCS can be proud of this important legacy. The book and the Journals are significant educational tools for anyone interested in the history of polar exploration. In ‘Number Nine’ I publish, in full, a lecture (together with a synthesised timeline) delivered by your editor on 20th May 2017 in Dundee at a polar convention. It is entitled ‘The Ross Sea Party – Debacle or Miracle? The RSP has always fascinated me and in researching for this lecture my eyes were opened to the truly incredible (and often unsung) achievements of this ill-fated expedition. -

'Post-Heroic' Ages of British Antarctic Exploration

The ‘Heroic’ and ‘Post-Heroic’ Ages of British Antarctic Exploration: A Consideration of Differences and Continuity By Stephen Haddelsey FRGS Submitted for Ph.D. by Publication University of East Anglia School of Humanities November 2014 Supervisor: Dr Camilla Schofield This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there-from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Synopsis This discussion is based on the following sources: 1. Stephen Haddelsey, Charles Lever: The Lost Victorian (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe Ltd, 2000) 2. Stephen Haddelsey, Born Adventurer: The Life of Frank Bickerton, Antarctic Pioneer (Sutton Publishing, 2005) 3. Stephen Haddelsey, Ice Captain: The Life of J.R. Stenhouse (The History Press, 2008) 4. Stephen Haddelsey, Shackleton’s Dream: Fuchs, Hillary & The Crossing of Antarctica (The History Press, 2012) 5. Stephen Haddelsey with Alan Carroll, Operation Tabarin: Britain’s Secret Wartime Expedition to Antarctica, 1944-46 (The History Press, 2014) Word Count: 20,045 (with an additional 2,812 words in the acknowledgements & bibliography) 2 Table of Contents 1. Approach 4 2. The ‘Heroic’ and ‘Post-Heroic’ Ages of British Antarctic Exploration: A Consideration of Differences and Continuity 35 3. Acknowledgements 76 4. Bibliography 77 3 Approach Introduction Hitherto, popular historians of British -

Prospectus 21/22

PROSPECTUS 21/22PROSPECTUS LONDON’S TRINITY CREATIVE LABAN CONSERVATOIRE CONTENTS 3 We are Trinity Laban 54 Music 4 A Trinity Laban Student is... 58 Performance Environment 6 London Life 60 Music Programmes 8 Our Home in London 60 Foundation Year Programmes 61 Undergraduate Programmes 10 Student Life 64 Graduate Diplomas 65 Masters Programmes 10 Accommodation 66 Advanced Diploma Programmes 11 Students’ Union 67 Blended Learning Programmes 12 Supporting Students 68 Music Faculty Staff International Students 14 14 English Language Support 70 Principal Study Global Links 16 72 Composition 74 Jazz 18 Professional Partnerships 76 Keyboard 78 Strings 20 CoLab 80 Vocal Studies 82 Wind, Brass & Percussion 22 Industry Insights 86 Specialist Studies 24 Research 88 Music Education 26 Dance 90 Popular Music 30 Dance Faculty Staff 94 Careers in Music 32 Performance Environment 96 Music Alumni 34 Transitions Dance Company 100 Musical Theatre 36 Dance Programmes 104 Foundation Programme in Musical Theatre 105 BA (Hons) Musical Theatre Performance 36 Foundation Year Programmes 106 Careers in Musical Theatre 37 Undergraduate Programmes 40 Masters Programmes 110 How to Apply 44 Diploma Programmes 112 Auditions & Selection Days 46 Careers in Dance 114 Fees, Funding & Scholarships 48 Dance Alumni 118 How to Find Us WE ARE TRINITY LABAN LONDON’S CREATIVE CONSERVATOIRE A global community An innovative, dynamic and diverse hive of creativity Trinity Laban is genre-defining, pushing the boundaries of music, dance and musical theatre. Here, you will build upon a foundation of technical excellence to create high quality, innovative work. You will develop the skills to produce your own performances in addition to honing your craft. -

Register of BUGB Accredited Ministers As at June 2021

Register of BUGB Accredited Ministers as at June 2021 Abbott, Brenda Dorothy East Midland Baptist Association Retired and Living in NOTTINGHAM Abbott, Neil Lewis South West Baptist Association Living in TORQUAY Abdelmasih, Hany William Yacoub London Baptists Regional Minister London Baptists Abdelmassih, Wagih Fahmy London Baptists Minister London Arabic Evangelical Church SIPSON and Tasso Baptist Church FULHAM Abel Boanerges, Seidel Sumanth London Baptists Tutor Spurgeon's College Abernethy, Mark Alan London Baptists Minister Mission Focussed Ministry Abraham, Keith London Baptists Minister Claremont Free Church CRICKLEWOOD Abramian, Samuel Edward Eastern Baptist Association Living in INGOLDISTHORPE Ackerman, Samuel Spencer Southern Counties Baptist Association Minister Horndean Baptist Church HORNDEAN Adams, David George Eastern Baptist Association Retired and Living in NORWICH Adams, John Leslie South West Baptist Association Retired and Living in SALTASH Adams, Robin Roy Northern Baptist Association Minister Beacon Lough Baptist Church GATESHEAD Adams, Wayne Malcolm South Wales Baptist Association Minister Presbyterian Church of Wales PORT TALBOT Adamson, Nicholas Edward Southern Counties Baptist Association Chaplain Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals DORSET Adebajo, Adenike Folashade Yorkshire Baptist Association Minister Network Church Sheffield: St Thomas Philadelphia SHEFFIELD Adjem, Yaw Agyapong London Baptists Minister Faith Baptist Church LONDON Adolphe, Kenneth James Chaplain HM Forces Afriyie, Alexander Oduro Osei