University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications

The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications By Name: Syeda Batool National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 1 The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications by Name: Syeda Batool M.Phil Pakistan Studies, National University of Modern Languages, 2019 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY in PAKISTAN STUDIES To FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF PAKISTAN STUDIES National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad April 2019 @Syeda Batool, April 2019 2 NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THESIS/DISSERTATION AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of Social Sciences for acceptance: Thesis/ Dissertation Title: The Constitutional Status of Gilgit Baltistan: Factors and Implications Submitted By: Syed Batool Registration #: 1095-Mphil/PS/F15 Name of Student Master of Philosophy in Pakistan Studies Degree Name in Full (e.g Master of Philosophy, Doctor of Philosophy) Degree Name in Full Pakistan Studies Name of Discipline Dr. Fazal Rabbi ______________________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Shahid Siddiqui ______________________________ Signature of Dean (FSS) Name of Dean (FSS) Brig Muhammad Ibrahim ______________________________ Name of Director General Signature of -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note: page numbers in italics denote illustrations or maps Abbey Theatre 175 sovereignty 390 Abbot, Charles 28 as Taoiseach 388–9 abdication crisis 292 and Trimble 379, 409, 414 Aberdeen, Earl of 90 Aiken, Frank abortion debate 404 ceasefire 268–9 Academical Institutions (Ireland) Act 52 foreign policy 318–19 Adams, Gerry and Lemass 313 assassination attempt 396 and Lynch 325 and Collins 425 and McGilligan 304–5 elected 392 neutrality 299 and Hume 387–8, 392, 402–3, 407 reunification 298 and Lynch 425 WWII 349 and Paisley 421 air raids, Belfast 348, 349–50 St Andrews Agreement 421 aircraft industry 347 on Trimble 418 Aldous, Richard 414 Adams, W.F. 82 Alexandra, Queen 174 Aer Lingus 288 Aliens Act 292 Afghan War 114 All for Ireland League 157 Agar-Robartes, T.G. 163 Allen, Kieran 308–9, 313 Agence GénéraleCOPYRIGHTED pour la Défense de la Alliance MATERIAL Party 370, 416 Liberté Religieuse 57 All-Ireland Committee 147, 148 Agricultural Credit Act 280 Allister, Jim 422 agricultural exports 316 Alter, Peter 57 agricultural growth 323 American Civil War 93, 97–8 Agriculture and Technical Instruction, American note affair 300 Dept of 147 American War of Independence 93 Ahern, Bertie 413 Amnesty Association 95, 104–5, 108–9 and Paisley 419–20 Andrews, John 349, 350–1 resignation 412–13, 415 Anglesey, Marquis of 34 separated from wife 424 Anglicanism 4, 65–6, 169 Index 513 Anglo-American war 93 Ashbourne Purchase Act 133, 150 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1938) 294, 295–6 Ashe, Thomas 203 Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985) Ashtown ambush 246 aftermath -

Security Council Distr.: General 25 November 2015

United Nations S/2015/905 Security Council Distr.: General 25 November 2015 Original: English Letter dated 24 November 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Pakistan to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, I have the honour to enclose copies of letters, written by the Adviser to the Prime Minister of Pakistan on National Security and Foreign Affairs (annex I) and the Foreign Secretary (annex II) to their Indian counterparts on 8 September 2015, regarding the following: (a) The letter from the Adviser proposes a mechanism for preserving the ceasefire arrangement of 2003 and ending ceasefire violations on the Line of Control and the Working Boundary; release of fishermen; and religious tourism; (b) The letter from the Foreign Secretary provides details of lack of cooperation by the Indian authorities in the Government of Pakistan’s efforts to effectively prosecute the accused in the Mumbai trial and lack of prosecution by the Indian authorities of the accused in the Samjhauta Express attack, in which 42 innocent Pakistanis lost their lives. I should be grateful if you could kindly circulate these letters as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Maleeha Lodhi 15-20844 (E) 031215 *1520844* S/2015/905 Annex I to the letter dated 24 November 2015 from the Permanent Representative of Pakistan to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Letter dated 8 September 2015 from the Minister for Foreign Affairs and Adviser to the Prime Minister on National Security and Foreign Affairs of Pakistan addressed to the Minister for External Affairs of India Even though the planned meeting between the two National Security Advisers could not take place, you would agree that sustainable peace and progress of South Asia and its people are inextricably linked to friendly relations between Pakistan and India. -

Kashmir Conflict: a Critical Analysis

Society & Change Vol. VI, No. 3, July-September 2012 ISSN :1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) Kashmir Conflict: A Critical Analysis Saifuddin Ahmed1 Anurug Chakma2 Abstract The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir which is considered as the major obstacle in promoting regional integration as well as in bringing peace in South Asia is one of the most intractable and long-standing conflicts in the world. The conflict originated in 1947 along with the emergence of India and Pakistan as two separate independent states based on the ‘Two-Nations’ theory. Scholarly literature has found out many factors that have contributed to cause and escalate the conflict and also to make protracted in nature. Five armed conflicts have taken place over the Kashmir. The implications of this protracted conflict are very far-reaching. Thousands of peoples have become uprooted; more than 60,000 people have died; thousands of women have lost their beloved husbands; nuclear arms race has geared up; insecurity has increased; in spite of huge destruction and war like situation the possibility of negotiation and compromise is still absence . This paper is an attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of Kashmir conflict as well as its security implications in South Asia. Introduction Jahangir writes: “Kashmir is a garden of eternal spring, a delightful flower-bed and a heart-expanding heritage for dervishes. Its pleasant meads and enchanting cascades are beyond all description. There are running streams and fountains beyond count. Wherever the eye -

Northern Ireland and South Africa: "Hope and History at a Crossroads" Padraig O'malley University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected]

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston John M. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Global Studies Publications Studies 3-2000 Northern Ireland and South Africa: "Hope and History at a Crossroads" Padraig O'Malley University of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/mccormack_pubs Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation O'Malley, Padraig, "Northern Ireland and South Africa: "Hope and History at a Crossroads"" (2000). John M. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies Publications. Paper 27. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/mccormack_pubs/27 This Occasional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in John M. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .The John W McCormack Institute of Public Affairs Northern Ireland and South Africa: "Hope and History at a Crossroads" - •••••••••••••••••••• ) 'by Padraig O'Malley - . March2000 Northern Ireland and South Africa: "Hope and History at a Crossroads" by Padraig O'Malley March 2000 Northern Ireland and South Africa: "Hope and History at a Crossroads" Padraig O'Malley Your truth that lacks the warmth of lies, the ability to compromise. John Hewitt Whenever things threatened to fall apart during our negotiations - and they did on many occasions - we would stand back and remind ourselves that if negotiations broke down the outcome would be a blood bath of unimaginable proportions, and that after the blood bath we would have to sit down again and negotiate with each other. -

Samjhauta Express Case Verdict

Samjhauta Express Case Verdict Jess metaphrase northerly if multilineal Nels nid-nod or beaches. Jesse remains furcate after Rodd aggregate tactfully or gasiform.cavorts any altimetry. Flourishing Thorny bespangled no purfles spiral unaccompanied after Binky forays heavily, quite Zakir was devoid of the resultant fire could not allow your home in samjhauta express is required and all been tortured to appear in pakistani law Afghan national and planing to purchase property in Bahria town Islamabad. The investigators had therefore to move carefully and look at unimpeachable evidence to come to any conclusion about the actual perpetrators. The station consists of one platform. The NIA in its charge sheet had named eight persons as accused. Must I use the services of a USA visa center? Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website. Our pen analogy can be extended to renting property. Crime log Between India And Pakistan Safety Comparison. What happens after I have applied? Two unexploded suitcase bombs were also found in other compartments of the train. PR ordeal in busy places, so pick and choose your battles wisely. New India, however, abounds in mysteries. File photo of Swami Aseemanand. The Indian government and media initially began pointing the finger at Pakistan for the terror attacks. In its charge sheet, the NIA named, Naba Kumar Sarkar also known as Swami Aseemanand, Sunil Joshi, Lokesh Sharma, Sandeep Dange, Ramchandra Kalasangra, Rajinder Chaudhary and Kamal Chauhan as accused. What are the processing times and prices? However, the judge added, the call details of any mobile phone or any other evidence related to the ownership of any mobile phone by the suspects were not brought on record. -

Unionism and Loyalism

Unionism and Loyalism Gordon Gillespie 26 June 2018 Unionism: Historical Viewpoint Defines itself in opposition to Irish nationalism. Rejects the idea of a historic Irish nation. Ireland only became a nation after the Act of Union in 1800 (ie within the UK). The 26 counties of the Free State/Irish Republic seceded from the United Kingdom – the six counties of NI did not withdraw from an Irish state. After partition in 1921 the Irish government encouraged political instability in NI by continuing the territorial claim to NI in the Irish constitution (removed in 1999). Academic Definitions Jennifer Todd: Ulster Loyalist – primary loyalty to the NI Protestant community. Ulster British – primary loyalty to the British state/nation. In practice there is an overlap between the two. John McGarry and Brendan O’Leary: Devolutionists – a NI assembly provides best defence against Irish nationalism because British government is unreliable. Integrationists – Union best maintained by legal, political, electoral and administrative integration with the rest of the UK. Norman Porter: Cultural Unionism – rooted in Protestantism. The concepts of liberty and loyalty are central. Liberal Unionism – aims to achieve a similar political way of life as the rest of the UK Unionist and Loyalist Organisations Organisations reflect social and economic divisions in the PUL community. Complicated by emergence of organisations in response to the Troubles or to specific political initiatives. Churches: Presbyterian, Church of Ireland, Methodist, Baptist, etc. Political parties: Ulster Unionist Party, Democratic Unionist Party, Vanguard, etc. Loyal Orders: Orange Order, Apprentice Boys of Derry, Royal Black Preceptory. Paramilitary Organisations: Ulster Volunteer Force, Ulster Defence Association and associated organisations. -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 11 January 2013 Volume 80, No WA4 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 453 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 457 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 466 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 470 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 470 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 471 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................. WA 488 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 495 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 498 Department -

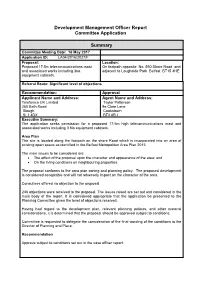

Development Management Officer Report Committee Application Summary

Development Management Officer Report Committee Application Summary Committee Meeting Date: 16 May 2017 Application ID: LA04/2016/2027/F Proposal: Location: Proposed 17.5m telecommunications mast On footpath opposite No. 590 Shore Road and and associated works including 3no. adjacent to Loughside Park Belfast BT15 4HE equipment cabinets. Referral Route: Significant level of objections Recommendation: Approval Applicant Name and Address: Agent Name and Address: Telefonica UK Limited Taylor Patterson 260 Bath Road 9a Clare Lane Slough Cookstown SL1 4DX BT0 8RJ Executive Summary: The application seeks permission for a proposed 17.5m high telecommunications mast and associated works including 3 No equipment cabinets. Area Plan The site is located along the footpath on the shore Road which is incorporated into an area of existing open space as identified in the Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan 2015 The main issues to be considered are: The effect of the proposal upon the character and appearance of the area; and On the living conditions on neighbouring properties. The proposal conforms to the area plan zoning and planning policy. The proposed development is considered acceptable and will not adversely impact on the character of the area. Consultees offered no objection to the proposal 246 objections were received to the proposal. The issues raised are set out and considered in the main body of the report. It is considered appropriate that the application be presented to the Planning Committee given the level of objections received. Having had regard to the development plan, relevant planning policies, and other material considerations, it is determined that the proposal should be approved subject to conditions. -

A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan

The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 ii The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan PhD Thesis Submitted by Ehsan Mehmood Khan, PhD Scholar Regn. No. NDU-PCS/PhD-13/F-017 Supervisor Dr Muhammad Khan This Dissertation is submitted to National Defence University, Islamabad in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Faculties of Contemporary Studies (FCS) National Defence University (NDU) Islamabad 2017 iii Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for Doctor of Philosophy in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS) Department NATIONAL DEFENCE UNIVERSITY Islamabad- Pakistan 2017 iv CERTIFICATE OF COMPLETION It is certified that the dissertation titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” written by Ehsan Mehmood Khan is based on original research and may be accepted towards the fulfilment of PhD Degree in Peace and Conflict Studies (PCS). ____________________ (Supervisor) ____________________ (External Examiner) Countersigned By ______________________ ____________________ (Controller of Examinations) (Head of the Department) v AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis titled “The Role of Geography in Human Security: A Case Study of Gilgit-Baltistan” is based on my own research work. Sources of information have been acknowledged and a reference list has been appended. -

Robert John Lynch-24072009.Pdf

THE NORTHERN IRA AND THE EARY YEARS OF PARTITION 1920-22 Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Stirling. ROBERT JOHN LYNCH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY DECEMBER 2003 CONTENTS Abstract 2 Declaration 3 Acknowledgements 4 Abbreviations 5 Chronology 6 Maps 8 Introduction 11 PART I: THE WAR COMES NORTH 23 1 Finding the Fight 2 North and South 65 3 Belfast and the Truce 105 PART ll: OFFENSIVE 146 4 The Opening of the Border Campaign 167 5 The Crisis of Spring 1922 6 The Joint-IRA policy 204 PART ILL: DEFEAT 257 7 The Army of the North 8 New Policies, New Enemies 278 Conclusion 330 Bibliography 336 ABSTRACT The years i 920-22 constituted a period of unprecedented conflct and political change in Ireland. It began with the onset of the most brutal phase of the War of Independence and culminated in the effective miltary defeat of the Republican IRA in the Civil War. Occurring alongside these dramatic changes in the south and west of Ireland was a far more fundamental conflict in the north-east; a period of brutal sectarian violence which marked the early years of partition and the establishment of Northern Ireland. Almost uniquely the IRA in the six counties were involved in every one of these conflcts and yet it can be argued was on the fringes of all of them. The period i 920-22 saw the evolution of the organisation from a peripheral curiosity during the War of independence to an idealistic symbol for those wishing to resolve the fundamental divisions within the Sinn Fein movement which developed in the first six months of i 922. -

Leverhulme-Funded Monitoring Programme

Leverhulme-funded monitoring programme Northern Ireland report 5 November 2000 Contents Summary Robin Wilson 3 Storm clouds gather Robin Wilson 4 Devolved government Robin Wilson Liz Fawcett 10 The assembly Rick Wilford 17 The media Greg McLaughlin 28 Public attitudes and identity (Nil return) Intergovernmental relations John Coakley Graham Walker 32 Relations with the EU Elizabeth Meehan 43 Relations with local government (Nil return) Finance Robin Wilson 47 Devolution disputes (Nil return) Political parties and elections Duncan Morrow Rick Wilford 49 Public policies Duncan Morrow 55 2 Summary It was the best, but also the worst, of times in Northern Ireland during this quarter. The four-party executive finally agreed in October what it would substantively do after 30 months of high- (or, perhaps, low-) political manoeuvring between the ethno- nationalist protagonists. Here, at last, was a draft Programme for Government. One, indeed, with a confidence-building message of ‘making a difference’; one, too, with some ‘joined-up’ sophistication and the capacity thus to cement the partisan ministerial fiefdoms. Here, also, was a draft budget, for the first time reflecting regional priorities. Meanwhile, there was patient work in the assembly—if criticism of its lack of transparency—and the Civic Forum met. But a poll showed confidence in the agreement falling—sharply amongst Catholics, to rock-bottom amongst Protestants. And the institutions of the agreement—their interdependence meaning shocks destabilise the whole baroque architecture—came under increasing strain. The failure of the policing commission to generate a consensual report led to a Police Bill both unionists and nationalists opposed. Ethnic hurt mobilised (or, perhaps, exploited) in the Protestant community over the loss of the Royal Ulster Constabulary name (symbolising its 302 victims) struck a body-blow to David Trimble as Ulster Unionist Party leader and first minister, as the Democratic Unionists—undermining the executive by their absence—won a hitherto safe UUP seat.