Nationalism at Eurovision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Webarts.Com.Cy Loreen Euphoria

webarts.com.cy Social Monitor Report Loreen Euphoria Overall Results 500 425 375 250 125 75 5/24 5/25 5/26 1,670 Total Mentions 1,592 Positive 556.67 Mentions / Day 21 Neutral 97.0 Average Sentiment 57 Negative 97.0 Date Source Author Content 5/26/2012 Twitter marcus_fletcher RT @_Trademark_: Trademark's tip for Eurovision this evening (Positive) is Euphoria by Loreen for Sweden. Englebert's song is a load of rubbish. #Eurovision - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter hechulera #np Euphoria-Loreen - twitter.com (Positive) 5/26/2012 Twitter terrycambelbal Euphoria-Loreen... my winner of this evening ! :) I know she will (Positive) made it. - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter egochic Ey! #Europe lets #vote for #SWEDEN and our amazing (Positive) #LOREEN tonite. #EUPHORIA is the #BEST song in years #ESC12 #ESC2012 #Eurovision #WINNING - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter oksee_l We're going u-u-u-u-u-up...Euphoria!!!!! #ESC2012 #esc12se (Positive) #eurovision #Loreen12p #sweden #Loreen - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter berrie69 "Loreen - Euphoria (Acoustic Version) live at Nobel Brothers (Positive) Museum in Baku" http://t.co/C0ycCR69 - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter mahejter RT @HladnaTastatura: See ya next year in Stockholm... (Positive) #NowPlaying Loreen - Euphoria - twitter.com 5/26/2012 Twitter garthy2008 DJGarthy: Loreen - Euphoria http://t.co/xXj4j8Il - twitter.com (Positive) 5/26/2012 Twitter nicoletterancic Loreen Euphoria (Sweden Eurovision Song Contest 2012) (Positive) COVER http://t.co/Oz6AyPFd via @youtube Please watch and share,thanx :** - twitter.com Webarts Ltd 2012 © All rights reserved Page 1 of 38 webarts.com.cy Social Monitor Report (continued) Date Source Author Content 5/26/2012 Twitter elliethepink @bbceurovision i'll be eating a #partyringbiscuit every time (Positive) Sweden score "douze pointes". -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

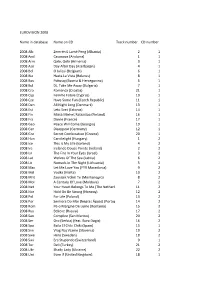

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

TRACKLIST and SONG THEMES 1. Father

TRACKLIST and SONG THEMES 1. Father (Mindful Anthem) 2. Mindful on that Beat (Mindful Dancing) 3. MindfOuuuuul (Mindful Listening) 4. Offa Me (Respond Vs. React) 5. Estoy Presente (JG Lyrics) (Mindful Anthem) 6. (Breathe) In-n-Out (Mindful Breathing) 7. Love4Me (Heartfulness to Self) 8. Mindful Thinker (Mindful Thinking) 9. Hold (Anchor Spot) 10. Don't (Hold It In) (Mindful Emotions) 11. Gave Me Life (Gratitude & Heartfulness) 12. PFC (Brain Science) 13. Emotions Show Up (Jason Lyrics) (Mindful Emotions) 14. Thankful (Mindful Gratitude) 15. Mind Controlla (Non-Judgement) LYRICS: FATHER (Mindful Sits) Aneesa Strings HOOK: (You're the only power) Beautiful Morning, started out with my Mindful Sit Gotta keep it going, all day long and Beautiful Morning, started out with my Mindful Sit Gotta keep it going... I just wanna feel liberated I… I just wanna feel liberated I… If I ever instigated I am sorry Tell me who else here can relate? VERSE 1: If I say something heartful Trying to fill up her bucket and she replies with a put-down She's gon' empty my bucket I try to stay respectful Mindful breaths are so helpful She'll get under your skin if you let her But these mindful skills might help her She might not wanna talk about She might just wanna walk about it She might not even wanna say nothing But she know her body feel something Keep on moving till you feel nothing Remind her what she was angry for These yoga poses help for sure She know just what she want, she wanna wake up… HOOK MINDFUL ON THAT BEAT Coco Peila + Hazel Rose INTRO: Oh my God… Ms. -

O.Staniulionis: “Visi Šokiai Yra Apie Meilę”

Vaikystėje Olegas Staniulionis mokėsi akrobatikos - ruošėsi dirbti cirke Sauliaus Venckaus nuotr. O.Staniulionis: “Visi šokiai yra apie meilę” Jo sukurtus šokius kiekvieną labai dėl šito stresuoju. Restoranuo- - Kokie “Tu gali šokti” šokėjai - Retai. Nebent į pasaulio čem- tys būna šokiuose, nuolat galvoju se šokau nuo 17 metų. Duoną val- būna per repeticijas? Ar verda pionatą nuvažiuoju pašokti. Bet jau apie tai, ką galima padaryti šokių sekmadienį mato TV3 žiūrovai, gau tik iš šokio, nors turiu dar tris aistros? Kunkuliuoja emocijos? jaučiu, kad esu nebe dvidešimties. aikštelėje. stebintys projektą “Tu gali šok- specialybes. - Kartais įsidūksta šokėjai, tada Darai ekstremalesnius judesius ir reikia pakelti balsą. jau bijai susižaloti. O anksčiau taip - Kas būdinga šokėjams? ti”. Kartais kamera atsigręžia ir - Kokias? nebūdavo - darydavai ir darydavai - Jie visada šneka apie šokius. į jį patį - pasislėpusį po kepure - Šaltkalvio-montuotojo, elek- - Ir klauso? negalvodamas. Bent jau mano pažįstami. tros suvirintojo ir dar siuvėjo. Atli- - Klauso, ačiū Dievui. su snapeliu, susikaupusį ir šiek kau 3 mėnesių praktiką “Lelijos” - Kokios dažniausios šokėjų - Kokie profesiniai ateities tiek nervingą, sergantį už savo fabrike. (Šypsosi.) Dabar neturiu jo- - O jei kas neišeina? patiriamos traumos? planai? kio vargo, kai reikia susitvarkyti ko- - Jei tikrai neišeina, aiškinu dar - Stuburo, kojų. Būna, eini gatve - Norėtųsi daugiau kurti - staty- šokėjus. Savamokslis, pradė- kį drabužį. kartą. Bet šiaip - atėjai į projektą, ir niksteli koją. Kai šoki, dažniausiai ti šokius. jęs gatvės šokius šokti kai dar vadinasi, turi daryti. nieko nenutinka, nes esi įpratęs - Kaip manai, ką šokėjai išsi- kontroliuoti kūną. O kai eini gatve, - Ar šokėjas gali vartoti alko- nebuvo “YouTube”. Vienas įspū- neš iš projekto “Tu gali šokti”? - Kiek laiko projekto šokėjai būni išsiblaškęs, atsipalaidavęs ir holį, rūkyti? dingiausių jo turimų apdovano- - Laimėtojai - pinigus. -

MA Thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics

MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 1 The Stylistics of Language Switches in Lyrics of Entries of the Eurovision Song Contest MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 2 Acknowledgements It did not come as a surprise to the people around me when I told them that the subject for my Master’s thesis was going to be based on the Eurovision Song Contest. Ever since I was a little boy I have been a fan, and some might even say that I became somewhat obsessed, for which I cannot really blame them. Moreover, I have always had a special interest in mixed language songs, so linking the two subjects seemed only natural. Thanks to a rather unfortunate turn of events, this thesis took a lot longer to write than was initially planned, but nevertheless, here it is. Special thanks are in order for my supervisor, Tony Foster, who has helped me in many ways during this time. I would also like to thank a number of other people for various reasons. The second reader Lettie Dorst. My mother, for being the reason I got involved with the Eurovision Song Contest. My father, for putting up with my seemingly endless collection of Eurovision MP3s in the car. -

CHAPTER 3 Frege 1 Chapter 3 LOT Meets Frege's Problem (Among

CHAPTER 3 Frege Chapter 3 LOT Meets Frege’s Problem (Among Others). Introduction Here are two closely related issues that a theory of intentional mental states and processes might reasonably be expected to address: Frege’s Problem and the Problem of Publicity1. In this chapter, I’d like to convince you of what I sometimes almost believe myself: that an LOT version of RTM has the resources to cope with both of them. I’d like to; but since I’m sure I won’t, I’ll settle for a survey of the relevant geography as viewed from an RTM/LOT perspective. Frege’s Problem If reference is all there is to meaning, then the substitution of coreferring expressions in a linguistic formula should preserve truth. Of course it should: if `Fa’ is true, and if `a’ and `b’ refer to the same, how could `Fb’ not be true too? But it’s notorious that there are cases (what I’ll call `Frege cases’) where the substitution of coreferring expressions doesn’t, preserve truth; it’s old news that John can reasonably wonder whether Cicero is Tully but not whether Tully is; and so forth. It would seem to follow that reference can’t be all there is to meaning. Worse still, it’s common ground (more or less) that synonymous expressions do substitute salve veritate, even in prepositional attitude (PA) contexts.2. So, it seems, that substitution requires something less than synonymy but something more than coreference. Since senses are, practically by 1 A concept is `public’ iff (I) more than one mind can have it and (ii) if one time-slice of a given mind can have it, others can too. -

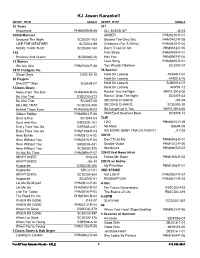

2 Column Indented

KJ Jason Karaoke!! ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years 311 Wasteland PHM0509-R-09 ALL MIXED UP J5-13 10000 Maniacs AMBER PHM0210-R-01 Because The Night SCDG01-163 Beyond The Grey Sky PHM0402-R-05 LIKE THE WEATHER SCDG03-89 Creatures (For A While) PHM0310-R-04 MORE THAN THIS SCDG03-144 Don't Tread On Me PHM0512-P-05 112 First Straw PHM0409-R-01 Peaches And Cream SGB0065-18 Hey You PHM0907-P-04 12 Stones Love Song PHM0405-R-01 We Are One PHM1008-P-08 You Wouldn't Believe SC3267-07 1910 Fruitgum Co. 38 Special Simon Says DKG-34-15 Hold On Loosely ASK69-1-01 20 Fingers Hold On Loosely AH8015-16 Short D*** Man SC8169-07 Hold On Loosely SGB0016-07 3 Doors Down Hold On Loosely AHP01-12 Away From The Sun PHM0404-R-05 Rockin' Into the Night MKP2 2916-05 Be Like That E3SCDG-373 Rockin' Onto The Night SC8479-03 Be Like That SC3267-08 SECOND CHANCE J91-08 BE LIKE THAT SCDG03-456 SECOND CHANCE SCDG02-30 Behind Those Eyes PHM0506-R-03 So Caught up in You MKP2 2916-06 Citizen Soldier PHM0903-P-08 Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC8479-14 Duck & Run SC3244-03 3LW Duck and Run E4SCDG-161 I DO PHM0210-P-09 Every Time You Go ESP509-4-01 No More G8604-05 Every Time You Go PHM1108-P-03 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) J17-08 Here By Me PHM0512-A-02 3OH!3 Here Without You PHM0310-P-04 Don't Trust Me PHM0903-P-01 Here Without You E6SCDG-431 Double Vision PHM1012-P-05 Here Without You SCDG00-375 StarStrukk PHM0907-P-07 It's Not My Time PHM0806-P-07 3OH!3 feat Neon Hitch KRYPTONITE J108-03 Follow Me Down PHM1006-P-08 KRYPTONITE J36-14 3OH!3 w/ Ke$ha Kryptonite -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski pped My Rating Because The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 4149082 165 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# DF7AFDAC Carry That Weight The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 2501496 96 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 74 DF4189 Come Together The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 6431772 260 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 5081C2D4 The End The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 3532174 139 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 909B4CD9 Golden Slumbers The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 2374226 91 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# D91DAA47 Her Majesty The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 731642 23 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 8427BD1F 1 02.07.2011 13:33 Here Comes The Sun The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 4629955 185 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 23 6DC926 3 30.10.2011 18:20 4 02.07.2011 13:34 I Want You The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 11388347 467 1969 02.07.2011 13:38 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 97501696 Maxwell's Silver Hammer The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 5150946 207 1969 02.07.2011 13:38 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 78 0B3499 Mean Mr Mustard The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 1767349 66 1969